I should have seen it coming. I suppose I expected a more gradual transition to my pre-pandemic activity level. You may recall that I confessed to being quite comfortable with quarantining. Professional obligations over the last four decades had pushed me out into the world and forced me to learn to interact fairly successfully with other people. But it was always hard. And always immensely exhausting. It wasn’t until we were all forced to withdraw from society that I realized just how heavenly that mandate was for me. I retreated into my little cocoon, taking walks with the dog and a friend or two, and being quite content with that abnormal state of things. I learned to talk on the phone more, which I had never particularly enjoyed, and I celebrated how infrequently my car left the garage. But now, I suppose, it’s over. Or at least the majority of people in my neck of the woods have decided the pandemic is behind us. The dictate now is that we must all return to our normal activities, sans masks, or risk being branded as pathetic snowflakes. I will admit that I have been one of the last to walk into a restaurant without a mask or accept an invitation to a gathering with more than a couple of people. I haven’t traveled since 2019. I haven’t been to an event since early 2020. All my socializing has been outdoors, usually on a hiking trail. And, quite frankly, I didn’t really want to leave the cozy little womb I had created. So I fretted about what to do. How should I respond to the onslaught of invitations landing in my inbox and on my phone? The rest of the world was moving on, and some—perhaps foolishly—seemed to think they wanted to bring me along. Thinking I was dipping my toe in the uninviting water, on April 20 I took a deep breath and met a friend for lunch…indoors. On April 22, I got my second Covid booster. And then, somehow, the floodgates opened. Was it just spring, and people wanting to get out from under our long winter? Was it the cyclical celebrations this season brings? Or perhaps it was the perceived freedom from the threat of the virus that resulted in an eruption of social invitations? I said yes. I put each one on my calendar. Maybe I really could do this. Maybe I could be in public among large groups of people without worrying about infecting some vulnerable soul near me. I managed a bridal shower. A concert. And then things started snowballing. I felt besieged by invitations. I couldn’t get sufficient air in-between them. My eating became erratic and sleeping was impossible. Even my daily calming rituals were upended. One evening, after two other events, I was walking Lucy and stumbled into a spontaneous retirement party at a neighbor’s firepit. The humans and canines in attendance were favorites of my dog. We got swallowed up. I couldn’t leave. Late last night I finally had to put the brakes on. I canceled a date I had made with a friend. I pushed breathing and exercising and quiet chores around the house to the top of my priority list. Clearly I will have to find a way to better manage these emerging social obligations and my friendships. If you are reading this, I hope you won’t take offense. I hope you won’t feel snubbed if I simply can’t add another activity to my calendar. I realize now I need to do this gradually, on my own terms. I need to get a grip. Avoid spontaneous combustion. I hope you will be patient with me. For my part, I will continue to fight the urge to disappear to a remote cabin in the woods without leaving a forwarding address. Coming Up Next: One final installment of the Richard the Terrible saga!

3 Comments

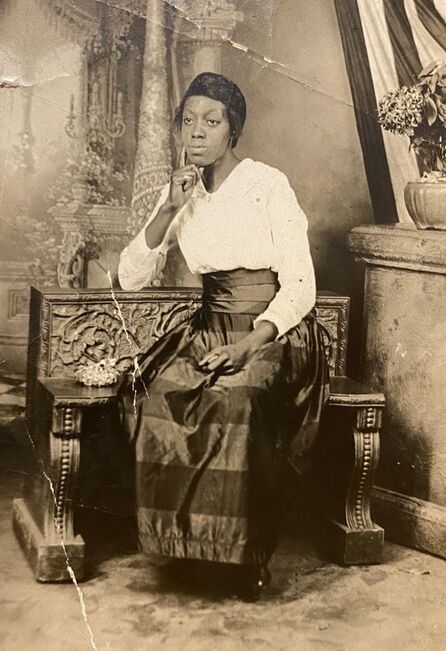

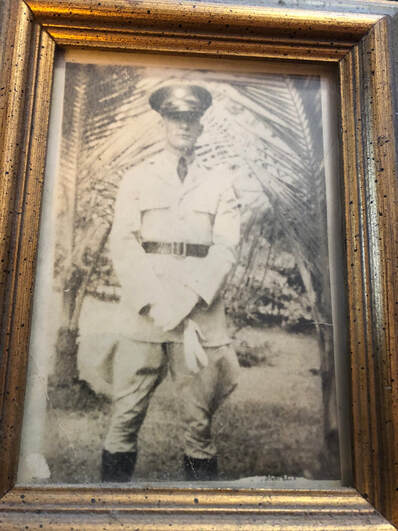

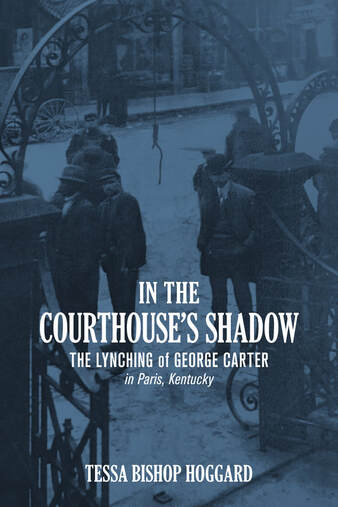

Katie Carter, the younger sister of George Carter and the grandmother of Jim Bannister. George Carter was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901. Photo provided by Jim's daughter, Cheryl. Katie Carter, the younger sister of George Carter and the grandmother of Jim Bannister. George Carter was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901. Photo provided by Jim's daughter, Cheryl. On February 23, 1900, Rep. George Henry White (R-N.C.), the sole Black U.S. lawmaker at the time, gave an impassioned speech on the House floor about the antilynching legislation he was proposing. The bill would make mob violence that resulted in the victim’s death a federal crime of treason to be tried in U.S. courts. White had felt compelled to act after witnessing the bloody Wilmington, N.C., race riot a little over a year before, during which a mob of white locals toppled the city’s multiracial government and ruthlessly murdered an estimated 60 innocent Black citizens. After White’s speech, his fellow congressmen applauded his words but failed to pass the bill out of committee. Thirty-five years after the Civil War, Southern devotion to states’ rights was still paramount. White called out some of his colleagues who had spoken against heinous lynchings in their own communities. In White’s view, these legislators would not countenance federal legislation because “this would not have accomplished the purpose of riveting public sentiment upon every colored man of the South as a rapist from whose brutal assaults every white woman must be protected.” [Washington Post, February 21, 2020] A year later, on February 11, 1901, a determined mob of local townsmen hung George Carter in front of the Bourbon County Courthouse in Paris, Ky. His crime? According to news reports: an attempted purse snatching. According to rumor and innuendo: rape.  My great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. My great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. The woman George Carter allegedly accosted was my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Board. The eight-year-old boy who identified Carter as his mother’s assailant was my maternal grandfather, William Lyons Board. There are reasons to question whether George Carter was indeed the man who assaulted my great-grandmother. There was no trial, no presentation of evidence. There was almost certainly no capital crime. In her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky, Paris native Tessa Bishop Hoggard scrutinizes the contemporaneous documentation and then offers a riveting account of the lead-up to the encounter with my great-grandmother and its chilling aftermath. The hanging also plays a pivotal role in the novel I wrote about my grandfather, Next Train Out. Of course, no one in that Paris, Ky., mob was ever identified or arrested. No one was charged or convicted of murdering George Carter. There was no federal hate crime or antilynching law on the books, because Congress had failed to act the year before. It was not until 1920 that “Kentucky became the first southern state to pass an antilynching law.” [John D. Wright Jr., “Lexington’s Suppression of the 1920 Will Lockett Lynch Mob,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 84, no. 3 (1986): 263-79.] This month, 122 years later, after 200 failed attempts, Congress finally succeeded in passing the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, named in honor of the 14-year-old boy who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. After President Biden signs the bill into law, a lynching resulting in death or serious bodily injury can be prosecuted as a federal hate crime punishable by up to 30 years in prison. It’s too late for George Carter, of course, or for the estimated 2,000 people who were lynched in this country after White’s original bill failed. But perhaps it’s a sign that our nation’s citizens are finally ready to take some initial steps toward ensuring justice prevails when racial hate crimes are committed. Just last month a Georgia jury found the three white men involved in Ahmaud Arbery’s murder guilty of federal hate crimes. The next day the three Minneapolis police officers who remained inert as Derek Chauvin slowly killed George Floyd were all found guilty of violating Floyd’s civil rights. It may feel like way too little way too late, but perhaps we can sense a slight rebalancing of the scales of justice. Perhaps we are moving at a snail’s pace toward that more perfect union where all men and women truly are created equal. Despite current efforts in statehouses across the country to restrict discussions of our nation’s documented history relating to racial injustice and oppression, perhaps these concrete actions are signs of movement in the opposite direction, toward transparency and a more honest reckoning of our past. We all need to feel uncomfortable about the atrocities that have been committed in this nation to buttress unequal power structures. We need to feel shame. And then we need to take action to address the lingering institutions and sentiments that perpetuate these injustices. Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill, the longtime champion of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, said after the bill passed: “Lynching is a longstanding and uniquely American weapon of racial terror that has for decades been used to maintain the white hierarchy…. [This bill] sends a clear and emphatic message that our nation will no longer ignore this shameful chapter of our history and that the full force of the U.S. federal government will always be brought to bear against those who commit this heinous act.” [NPR, March 7, 2022] Bill signedOn Tuesday, March 29, 2022, President Biden signed into law the Emmett Till Antilynching Act. Till’s cousin, Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., the last living witness to his abduction, said in response, “Laws make you behave better, but they cannot legislate the heart.” Let’s hope the hearts of all Americans are slowly recognizing the injustices that have stained our nation since its inception. eventOn Saturday, March 26, 2022, Tessa Bishop Hoggard and I participated in a Zoom virtual conversation hosted by the Paris, Ky., Hopewell Museum. We discussed the 1901 lynching of George Carter and how that dark episode prompted both of us to write our books. Connecting with Tessa ultimately led to my friendship with George Carter’s great-nephew, Jim Bannister.  In June 1946, John C. “Pud” Goodlett travels third class from Bamberg to Le Havre before boarding a ship home. In June 1946, John C. “Pud” Goodlett travels third class from Bamberg to Le Havre before boarding a ship home. My father, the rule-follower. At least now I know where I get it. “It will always be a source of regret to me that I followed Army regulations and failed to keep a diary of my days in Europe from Jan 1945 to June 1946.” Pud wrote that in the Preface to the journal he started well after the war, in February 1953, while employed as a research associate at Harvard Forest in Petersham, Mass. Though this journal focuses on his efforts to complete his doctoral dissertation, his interactions with other scientists and their research projects, and his introduction to academic and work-life politics, he is nonetheless just a few years removed from his march across Europe as a lieutenant in Patton’s army. Every now and then, wartime memories would interrupt his typical journal remarks about New England weather or frost heaves, with no elaboration. The specific horrors or searing experiences that prompted a terse reference were not permitted to stain these pages. For example, here is how he opened his post on 31 March 1953: Eight years ago about this time I was crossing the Rhine at Mainz. This afternoon about 1600 the sun broke out and stayed until sunset. We’ve had about a week of lousy weather—rain or cool and cloudy. Rain gauge showed almost 3 in. for last week. Worcester had 8 in. rain in March—more than any March since 1936, the year of disastrous floods. Last weekend the Conn. and Saco Rivers were on the rampage. … After crossing the Rhine to Frankfurt, Pud and his unit would follow Germany’s 6th Infantry Division east to Mühlhausen, south to Erfurt, through the Thüringer Wald to the Danube at Regensburg, and eventually on to Austria. They encountered increasingly demoralized enemy forces and human atrocities unlike any the modern world had seen. My father witnessed all of this first-hand. As an intelligence staff officer and a battalion S2, Pud was responsible for relaying to his commander the threat that lay just ahead: the number of and preparation of the enemy forces, the terrain and battlefield conditions, and the risks to a successful completion of the mission. The accuracy of his assessment and the clarity of his communication could save—or cost—American lives. Amid the chaos of war, the Allied forces had one goal: the defeat of Hitler and the forces he had aligned behind the Nazis. The enemy was so clear, the purpose so important, that young American men, including members of my family, eagerly volunteered to fight, sometimes before they were of legal age to join the military. I recall this family history, of course, as Vladimir Putin sends Russian forces westward into Ukraine. Putin has his own reasons for this aggression, claiming, falsely, that the democratically elected Ukrainian government grabbed power illegitimately. Putin wants us to believe he is fighting the Nazis--“like 80 years ago.” He is not. But he believes that he can win support among Russian people if he resurrects the horror inflicted on millions of Russians during the Second World War. The Nazis were the clear enemy then, so they will be a convenient enemy now. We have all seen the rising influence of Nazi sympathies in recent years. It is a cancer that seems to metastasize unchecked in dim corners of civilized society. I expect Ukraine, like most Western countries, has some number of Nazi sympathizers. It is not, however, a nation ruled by Nazis. Our parents and grandparents fought the evil that was Nazism. As did the parents and grandparents of Russian citizens. And Ukrainian citizens. Putin’s forces today are not fighting Nazism. They have been conscripted to fight Putin’s war to realize his fever dream of an expanded Russian state. It is Putin who is using Nazi tactics like disinformation and a nationalistic love for the motherland to further his own totalitarian ambitions. We see this clearly. We ache for the Ukrainian and the Russian citizens; the refugees and the nations that have opened their arms to them; the Russian soldiers who are being sent to fight their neighbors and their family members; the Ukrainian forces that are withstanding the assault of a larger, better equipped opponent; the Ukrainian citizens who are fighting back in the streets; the Ukrainian officials who are standing strong in the face of mortal threat and the physical destruction of their cities and their homes. Experts tell us this tragedy is still in its opening act. It’s hard to know how it will play out. We can only hope, once again, that the rest of the world can find the courage to stop a madman.  The author’s father, Corporal Joseph P. Anthony, circa 1940 in Hawaii. The author’s father, Corporal Joseph P. Anthony, circa 1940 in Hawaii. Joe Anthony, of Lexington, Ky., wonders whether Americans have what it takes to defeat our 21st-century enemy. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. During the 1940s, do you think our parents and grandparents would sometimes complain to each other? “I’m so tired of news about the war. Can’t we talk about something besides the Pacific Front or Allied landings?” I’m sure they did, occasionally, but they knew the war was center stage. Covid is our war. It doesn’t matter if we’re “over it.” Our enemy, Covid, is endlessly crafty, energetic, and vicious. I know. I recently spent 16 days in the hospital and nine days in a rehabilitation facility after contracting the virus. I was fully vaccinated and boosted, and it nearly broke me. As in all battles, it’s ourselves that matter even more than our opponents: our vanities, our fears, our prejudices, our malice. If we can manage ourselves, we will vanquish the enemy. George Will, the conservative columnist, wondered if our country, as constituted now, could win the Second World War. I wonder, too. It isn’t only the reluctance to sacrifice for the common good; it’s the refusal to believe the credible. Millions indulge themselves with fantastic speculation backed by no evidence and sometimes no logic and reject that which comes with freight-loads of scientific proof or that which they witnessed—re January 6th—with their own eyes. That refusal to acknowledge basic reality breaks down community, too. We can’t even get to the point of disagreeing. A sub-group of Americans in the ’40s, die-hard America-Firsters, pushed the theory that FDR had been behind the attack on Pearl Harbor. But they were called nuts by the huge majority. Now there is no “nut” theory that doesn’t get a hearing and eventually, it seems, a substantial following. Our parents and grandparents may have grumbled, but they collectively pulled themselves together: gathered scrap, rationed, and sent their sons to fight. They accepted hard truths, facts they didn’t like. They knew the news wasn’t always going to be good and didn’t reach for a scapegoat to blame. Well, not usually at least. And when the dreaded telegraph arrived, they grieved but knew their sacrifice went beyond themselves—went out to the country they loved. They got some comfort from knowing that. Though death is always solitary, the country they sacrificed for came back to them in a collective embrace. We love the same country. And if we truly love that country, it will love us. Can we do less than our previous generations? Can we even imagine loving our fellow Americans?  Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, surveys Georgia’s political landscape. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. Once again, it appears the state of Georgia will be the center of the political campaigning universe in the United States during 2022. With David Perdue’s entry into the gubernatorial race, the plot thickens. Months ago, when Herschel Walker announced his candidacy as a Republican opponent to Sen. Rev. Raphael Warnock, I started writing a post entitled “Run, Herschel, Run (right back to Texas).” Now his campaign is just one ingredient in the Georgia political stew. I still think it’s unethical for Herschel Walker to “move back” to Georgia two weeks before filing as a candidate to represent the people in a state he left in 2011. Walker also has a history of mental illness and alleged domestic violence. But this is politics, folks. Laws and ethics don’t seem to influence (or apply to) the behavior of many political figures. While some of us may believe it’s unethical, under the Constitution it is perfectly legal for him to run. Of course, University of Georgia football is a religion all its own, so Walker is like a god to many Dawgs fans. Plus, he may get the endorsement of 45, which will garner him much favor with the far-right crowd. The former president could be a significant problem for Brian Kemp in his campaign for re-election as Governor. If you recall, Kemp refused to help “find votes” to reverse Biden’s win in the Georgia presidential election. Now David Perdue presents a challenge as well. Democrats are quietly celebrating the entry of Perdue, as his candidacy will likely force a Republican run-off election. That makes three Republican gubernatorial candidates, including Big Lie supporter Vernon Jones. I’m sure there are bookies taking bets on who 45 will back: Perdue or Jones? What might he say or do to retaliate against Kemp’s disloyal behavior? Stay tuned for what is bound to be the worst kind of reality TV. Just a few years ago, the idea that Georgia would elect two Democratic U.S. Senators, and that we were a swing state that could win Democratic control of the Senate, would have been laughable. In many Georgia communities, the Democratic party did not field candidates in local and state legislative races for roughly 20 years. I have no doubt that voter registration and GOTV efforts for 2022 will be extraordinary. Stacey Abrams, her supporters, and the Fair Fight* organization excel at both. I believe electing Stacey Abrams Governor of Georgia will bring joy, hope, and continued motivation to Democrats, most African Americans, and many women. It will also represent a monumental achievement in a deep south state steeped in racism since colonial times. Sixteen miles east of Atlanta lies Stone Mountain Park, where the largest bas-relief artwork in the world—featuring three Confederate leaders—was completed in 1972. The 90-foot-tall engraving looms over the patrons of the public park from the façade of Stone Mountain. A portion of funds for the Confederate memorial project came from the federal government’s 1925 issuance of fifty-cent commemorative coins featuring two Confederate generals. (Yes, that’s right. The federal government issued coins to commemorate traitors, and to help fund a monument to them.) The Ku Klux Klan held a revival during a 1915 cross burning atop Stone Mountain. According to an article by Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Joshua Sharpe, the most recent KKK permit request to burn a cross atop Stone Mountain was in August 2017, the same month as the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. That permit was denied. In 2022, Georgians can elect Stacey Abrams as Governor and choose Renitta Shannon as Lieutenant Governor. Electing two African American women to top leadership in a state with such a sordid history around race and white supremacy will be a colossal achievement. In addition, we can select Georgia State House member, and daughter of Vietnamese refugees, Bee Nguyen as our next Secretary of State. And we can also choose gay State House member Matthew Wilson as our next Insurance Commissioner. I look forward to the day when electing someone of a particular gender, race, religion, or sexual orientation doesn’t signify a great advancement in our society. Until then, I’ll mark these candidacies and their political wins as monuments—monuments that signify progress for the entire human race. *Fair Fight works to register voters and protect voting rights across the United States. To learn more or get involved, visit https://fairfight.com/

The piercing shriek launched me from my position reclining on the sofa. I had landed there moments before after relinquishing my spot in the bed to my elderly dog, her whole body shaking in distress from the thunder and lightning and pounding rain. Was it the smoke alarm? I sniffed. No detectable smoke. I stumbled toward the sound. My cell phone was on the kitchen table, practically bouncing from the urgency of its alert. “Tornado Warning,” I saw on the screen. The phone rang—an old-fashioned ring from a land line—and when I picked up the receiver, I heard this simple message: “Tornado warning. Take cover.” I raced back to the living room, just as the siren near the front of our neighborhood began to wail. I turned on the TV to a local channel and heard, “The possible tornado is directly over the city of Frankfort heading toward northern Scott County.” That’s where I live.

I called out to Rick that we had to go to the basement. I dragged Lucy down the stairs and into the interior bathroom, grabbing my cell phone and a flashlight as I went. I turned up the TV in the basement to hear the reports and kept the bathroom door ajar. I heard Chris Bailey of WKYT say, “If you have a helmet—a batting helmet, a bicycle helmet, anything—put it on. Protect your head.” I made a mental note to store those old bike helmets in the bathroom. Then, “The suspected tornado is moving toward Peak’s Mill on its way toward Stamping Ground and Sadieville.” We were directly in its path. I watched the radar on my cell phone. The storm was moving fast. In a matter of minutes, it appeared the worst of it was skirting the northern edge of our neighborhood. And then it was gone. We escaped again. Although Stamping Ground, a small community in western Scott County, had suffered extensive damage from a smaller EF1 tornado just five days earlier, no other nearby areas were significantly affected by this storm. It was not until early Saturday morning, when I turned on the news, that I had any idea of the extent of the devastation to Kentucky and surrounding states. It’s almost a cliché, but tornadoes in particular make you wonder why you, your loved ones, your home were spared when others lost everything. In communities like Bowling Green, where the tornado made a more traditional swath of destruction, news images show one house demolished and the one across the street still standing, relatively unharmed. In Mayfield, unfortunately, there seem to be few random “lucky ones.” The storm appears to have annihilated most of the town. Many lives have been lost. As I type this, families are still searching. The grief and horror are immeasurable. The trauma to these communities will endure. The costs to rebuild will swell. Yet back in Scott County, the sun is shining and the sky is a brilliant blue. The crisp air invites you outdoors. The winds are finally calm. It’s hard to reconcile this pristine day with what I know has happened a couple hundred miles west. I’ll save my screed on climate change for another day. Today we are all thinking of those affected by these storms. Today, once again, I am wondering why my life has been left intact, as the wheel of fate continues to turn.  On June 25, gymnast Simone Biles was not having the Olympic Trials her fans had anticipated. She had stepped out of bounds, fallen off the beam, and not stuck a landing. She was still brilliant, of course. She is arguably one of the greatest athletes ever and she easily clinched the top spot on the U.S. Olympic team. But she was clearly not satisfied with her performance. After she finished her floor routine—eye-popping, as usual, but not perfect—the camera followed her to the sidelines. She sat down on the floor, reached into her backpack, and pulled out a long pair of shears to cut off the tape supporting her troublesome ankle. That task quickly dispatched, she reached into her backpack again and pulled out an almost comically large makeup brush. While the camera remained trained on her, she proceeded to powder her face. My jaw dropped. In the middle of an immensely significant athletic competition, one of the world’s greatest felt compelled to touch up her makeup. Perhaps the sheer ordinariness of that action calmed her. Perhaps it was a way to boost her confidence. But at a moment when she most needed to concentrate on her athletic performance, she was fixing her face. I was chagrined. Clearly I can’t ignore the fact that many, many female Olympians wear makeup and other cosmetic enhancements while competing. Eyelashes and fingernails of grotesque lengths are common. And how on earth do track athletes—male and female—run with necklaces and chains bouncing under their chins? I doubt these trends started in 1988 with Flo-Jo, but we all paid attention when she positioned herself in the starting blocks, her wickedly curved nails splayed on the track, her hair loose and flowing. This year, media reported as frequently on Sha’Carri Richardson’s flaming orange hair and outrageous fingernails as they did on her speed. Too bad we won’t get to see her perform in Tokyo. These fashionistas do succeed in grabbing our attention. But don’t they already do that with their athletic feats? Many, like the gymnasts, sometimes appear made up for a performance at the Grand Guignol. Why do they feel so compelled? As a youngster and a teenager I participated in nearly every sport available to girls at the time. I was notoriously average at all of them. But I loved being active, I loved the discipline it required, and I loved the harmony of a team effort. Being an athlete, no matter how ordinary, made me feel strong. It gave me confidence. But more than that, it allowed me to play a role other than “Sallie,” the socially awkward, too smart for her own good, outsider. Instead, I was the 4’11’’ hurdler or the feisty all-state midfielder or one of eight synchronized swimmers trying bravely to mimic the moves of the more experienced swimmers. I was gutsy, determined, fearless. As a teenage athlete, I could set aside, however momentarily, the fact that I wasn’t beautiful. I had no idea how to apply makeup to improve my appearance. With those two marks against me, finding acceptance at that age was difficult. But I could disappear on the tennis court or the hockey field. My sweat was worth something. My tenacity had value. So it makes me sad to see that, in 2021, many of our greatest athletes still view their looks as part of their performance. They have to be strikingly beautiful, perfectly coiffed, overly made up. Somehow they must feel that their athletic skills alone cannot validate their presence on the world stage. Years of training can only get them so far. Perhaps it’s the lure of lucrative promotional contracts that prompts them to make sure their appearance is as perfect as their performance. I wish young girls could see these athletes as the pure, powerful women they are. They don’t need fake eyelashes and fake fingernails and fake hair color to make a statement. They just need to demonstrate their prowess as heart-stopping, mind-blowing athletes. As the 2021 Olympics approached, several female athletes and their teams made the news for their attire. An official from England Athletics claimed that Welsh Paralympic world champion Olivia Breen’s sprint shorts—the Adidas official 2021 briefs—were too short. The European Handball Association's Disciplinary Commission fined the female Norwegian beach handball team when they showed up for a match in compression shorts similar to what the men wear rather than the mandated bikini bottoms. Black Olympic swimmers were denied the option of wearing the Soul Cap, a swim cap designed to better accommodate and protect their hair. Why can’t we just let women compete? Why does their appearance have to play such a large role? This morning I watched a men’s sand volleyball match, the men dressed comfortably in shorts and tank tops. I don’t have to tell you what the women are expected to wear.  Cicada crash. That’s an empty flask of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky you see. Some of these characters had a little too much fun. Photos by David Hoefer. Cicada crash. That’s an empty flask of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky you see. Some of these characters had a little too much fun. Photos by David Hoefer. David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, bids a fond farewell to the Brood X cicadas. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. The cicada bloom is finally starting to wind down in my neck of the woods (which is the Louisville Highlands). It is increasingly possible to hold an intelligible conversation with another human outside the house and to travel the sidewalks without the regular crunch of dead or dying bugs underfoot. That said, I had a final cicada experience that might be worth relating. I’m currently taking an online birding course through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (an organization whose praises I’ve sung previously on this blog). One of the exercises, called “sit-spotting,” involves sitting outdoors for 15 minutes, observing the immediate surroundings, and making note in a field journal of all that which most impinges on the five senses. In a Kentucky suburban environment, that ought to mean birds, squirrels, chipmunks, bees, cats, breezes, floral scents, etc. I did this a couple of weeks back, when the cicadas were still hot and heavy. Not wise. My entries read something like:

I’ll give the cicadas this: every 17 years they put on what is truly a command performance. I guess part of the diversity of nature that we always go on about, is that sometimes there is very little diversity at all.

The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. As I started working on Next Train Out, I knew that racial conflict had to be a theme of the novel. It seemed clear to me that the trajectory of Lyons Board’s life had to be predicated in part on his role, as an eight-year-old boy, in having a Black man lynched in his hometown, Paris, Ky., in 1901. As I researched the various cities and towns where my grandfather eventually lived, I found plenty of instances of racial unrest in their histories: mob violence, riots, lynchings, the obliteration of sections of towns where Blacks lived and prospered. Soon I began to better grasp the bigger picture, that the whole country was awash in deadly racial conflict just after World War I, when Black soldiers returned home expecting opportunities and respect in return for serving their country in the trenches in Europe. Instead, they found resentment and violence stoked by the belief among some white citizens that these returning veterans threatened their jobs and their status in the community. I learned about the Red Summer of 1919, which made me realize how widespread these race problems were. These confrontations were not isolated to the Deep South. They erupted in our nation’s capital, in Chicago, in New York and Omaha—in at least 60 locations from Arizona to Connecticut. How this anger and suspicion manifested itself in towns like Corbin, Ky., and Springfield, Ohio, are part of Lyons’ story. As we all now know, an area referred to as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Okla., waited until 1921 for its turn at center stage. On June 1, after 16 hours of horror, more than a thousand homes and scores of businesses had been incinerated. Somewhere between 100 and 300 people had been murdered. Thousands of Black survivors were then corralled into a detention camp of sorts and assigned forced labor cleaning up the mess the violent white mob had created. Before June 2020, when President Trump landed in Tulsa for a campaign rally originally scheduled to take place on Juneteenth, few Americans knew the lurid history of Black Wall Street. The facts had been suppressed, kept out of classrooms, out of the news, out of polite conversation. Black families in Tulsa passed down stories of violence and terror and escape—or stories of family members never seen again, their fates unknown. Few public officials dared recognize what had happened to all those people and their livelihoods and their property and their wealth. This year, on its 100th anniversary, the entire nation has been awakened to Tulsa’s tragic history. LeBron James produced a documentary—one of many. Tom Hanks wrote an op-ed. HBO made its Watchmen series accessible to more viewers. News forums of all types reported on the anniversary. Survivors of the massacre—all more than 100 years old--testified before Congress and met with President Biden. Under the leadership of Tulsa’s young white Republican mayor, G. T. Bynum, archaeologists have resumed the search for mass graves that had finally begun last summer. How a community like Tulsa now, finally, begins to reckon with its history is significant for all of us. We as a nation, as a collection of human beings, must break the silence we have permitted ourselves for generations and acknowledge how gravely we have wronged indigenous peoples, Blacks, and other minorities. How we blithely destroyed their culture, their history, their identities, and their lives. Acknowledging the truth is a start. Reporting historical facts is essential. Engaging in respectful, compassionate, and sensible discussion can prompt healing. Some communities—and even the U.S. Congress—are now beginning to discuss what reparations might look like. Other communities first need to simply acknowledge both the shame and the pain that have churned for decades among their citizens. When I first met with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of the man lynched because of an alleged incident with my great-grandmother, he made it clear that it was the silence that weighed most heavily on him. He had tried to learn more about the lynching of George Carter, but no one would talk about it. His elders wouldn’t talk about it. The Black community wouldn’t talk about it. Fear and shame and ongoing oppression had kept everyone close-mouthed for generations. The emotional damage accrued. The human damage. The not knowing. The not understanding.  With her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow, Tessa Bishop Hoggard provided the key that Jim needed to open the door to his family’s history. She pulled his story out of the shadows. Jim has told me repeatedly that he feels an extra spring in his step now that he knows the facts. He has found a peace that had eluded him all of his eighty years. In her interview with Tom Martin on WEKU’s Eastern Standard program this week, Tessa said, “As we peer into our history, hate crimes were a common daily occurrence….Accountability and consequences were absent. There was only silence. This silence is a form of complicity….Today is the time for acknowledgment and healing. Let the healing begin.” (Listen to the 10-minute interview.) We have to acknowledge our difficult history. We have to face what happened. And then we have to consider the steps, both small and large, that we can take to heal the wounds that will only continue to fester if we stubbornly ignore them.  This year, on the morning of Juneteenth (Saturday, June 19), I’ll have copies of Tessa’s book and my novel available for sale at the Lexington Farmers Market at Tandy Centennial Park and Pavilion in downtown Lexington, Ky. In August 2020, the citizens of Lexington agreed to rename Cheapside Park, the city’s nineteenth-century slave auction block and one of the largest slave markets in the South, the Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park, honoring the freed slave who did masonry work for many of Lexington’s landmarks, including laying the brick for the nearby historic Fayette County courthouse, built in 1899. One of the organizers of the “Take Back Cheapside” campaign, DeBraun Thomas, said at the time: “Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park is one of the first of many steps towards healing and reconciliation.” Fittingly, I’ll be at the Farmers Market as part of the Carnegie Center’s Homegrown Authors program. Tandy had a hand in the construction of Lexington’s beautiful neoclassical Carnegie Library on West Second Street in 1906, now the home of the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning. If you’re in Lexington that morning, stop by and we can continue this conversation.  The Brood X cicada is descending on the eastern U.S., from Illinois to New York and south to Georgia. Photos by David Hoefer. The Brood X cicada is descending on the eastern U.S., from Illinois to New York and south to Georgia. Photos by David Hoefer. David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, examines our latest plague. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. They’re here. In fact, they’re everywhere—gazillions of them. They’ve come up from holes in the ground, where they spent 17 years sucking nutrients from plant roots in the dark, biding their time until nature called them to invasion. With their cellophane wings and bulbous red eyes they look like something out of an Old Testament plague or maybe next-of-kin to the “Bug-eyed Monsters” (BEMs) that infested the covers of science-fiction pulp magazines from mid-20th century America. And the racket—an incessant loud thrumming from high in the air, as though alien spacecraft were massing behind tree cover or Saruman the White was working up his war engines, as described by Tolkien in The Lord of the Rings. Reportedly, that racket can raise noise levels in neighborhoods up to 100 decibels. What am I going on about? Why the 2021 vintage of Brood X cicadas, of course. You likely know the story by now. Brood X is number ten of 15 groups of periodical cicadas resident in eastern North America. It consists of three species and is the largest and most widespread of its kind. Brood X nymphs tunnel up from their underground lairs every 17 years, once soil temperatures reach 64 degrees Fahrenheit. They shed their exoskeletons, briefly taking on a final adult form. What follows is a furious few weeks of them discharging their Darwinian duty—flying, mating, laying eggs in the trees, and dying. And, yes, all that noisemaking—the male’s monochromatic version of a mating song. Brood X cicadas are estimated to emerge in the trillions, and species survival depends on it, because these defenseless insects make easy prey for a variety of birds and other hungry creatures (including my dog, who wolfs them down like a human chomping on potato chips—a protein supplement, I suppose). In the meantime, cicadas are as common as hydrogen, and getting into everything. You name it and they‘re on it—clothing, hair, cars, furniture, rugs, sidewalks, houses, and every other manifestation of human culture. Their weird insect noises and alien ugliness make them unwanted guests, but the fact is, unlike last year’s virus, they’re perfectly harmless. Brood X cicadas may be the ultimate proving ground for the philosophical notion of “live and let live.” Kentucky is not actually at the epicenter of Brood X, but the bugs are certainly present and accounted for in the Bluegrass State (including in great numbers in my treelined yard). Entomologists see this North American version of a locust visitation in effect until mid-July, when the survivors will begin a new 17-year cycle of root-sucking and apocalyptic emergence and transformation. The best we can do for now is batten down the hatches and learn to live with one of nature’s stranger life utterances. If you’re inclined toward more active observation, I can suggest an interesting application that is downloadable to iPhone and Android devices. Developed by an academic at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati and called Cicada Safari, it enables Joe and Josephine Test-tube to take on a citizen-scientist role during the Brood X interval by documenting local cicada activity with photographs and videos and posting them to an ever-growing database curated by the application’s sponsors. I’ve enjoyed running around my neighborhood looking for interesting shots, once I got over my initial repulsion. Just remember: the cicadas probably find us at least as hideous to contemplate. AddendumThere is no mention of cicadas in The Last Resort, which makes me think that John Goodlett didn’t observe them in the Lawrenceburg environs during 1942-43. Brood X outbreaks would have occurred in 1936 and 1953, outside of the journal’s timespan. But there are other broods on different schedules, waiting for long periods to climb into the light and then share the world with us, if only briefly.

|

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed