Steller’s Jay: Welcome to America. Steller’s Jay: Welcome to America. David Hoefer, co-editor of The Last Resort, shares a story of taxonomic serendipity. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. In a previous blog post, I discussed John Goodlett’s taxonomic activities at Camp Last Resort, where he identified and sketched living organisms (especially plants) as part of his undergraduate education at the University of Kentucky. Similar activities, recorded more scientifically in the Harvard Forest journal, indicate Pud’s gradual emergence as an upper-echelon botanist and plant geographer. As such, it’s been a pleasure to read Corey Ford’s Where the Sea Breaks Its Back, a biography of the German naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller, with its demonstration of the vital and even heroic role taxonomy can play in helping us understand our planetary home. Steller accompanied Vitus Bering on his second and last expedition into the then-uncharted northern waters between Asia and North America in 1741-42. It was this expedition that finally confirmed that the landmass east of Siberia was in fact that same North America then being colonized by other European powers on the Atlantic Coast and by the Spanish in Central America and what is today the Southwestern U.S. and California. And what was the final piece of the puzzle that completed this realization? From Cape St. Elias on Kayak Island, Alaska: “Perhaps no other naturalist in history ever accomplished so monumental a task under such difficulties and in so little time. It was four in the afternoon when Steller spread his specimens around him in the sand, and began to enter in his notebook the results of the previous six hours. When the yawl returned at five ‘o’ clock, he had completed his exhaustive report, the first scientific paper ever written on Alaskan natural history… “Some plants in his collection were already familiar to him from his earlier investigations in Kamchatka. He identified the upland cranberry, the red and black whortleberry, and a shrub he called the scurvy berry, probably the black crowberry. He was more enthusiastic over ‘a new elsewhere unknown species of raspberry,’ the salmonberry of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. Although the berries were not yet fully ripe, Steller was impressed by their ‘great size, shape, and delicious taste’… “The yawl brought what Steller ironically described as ‘the patriotic and courteous reply’ to his message to Bering, a brusque order to ‘betake myself on board quickly or they would leave me ashore without waiting for me.’ There were only three more hours left until sunset, barely time to ‘scrape together as much as possible before fleeing the country.’ He sent [his Cossack assistant] Lepekhin to shoot some strange and unknown birds he had noticed, easily distinguished from the European and Siberian species by their particularly bright coloring, and he started down the beach in the opposite direction, returning at sundown with his botanical collection. “Lepekhin had equally good luck. He ‘placed in my hands a single specimen, of which I remember to have seen a likeness painted in lively colors and described in the newest account of the birds of the Carolinas.’ Steller’s fantastic memory had recalled a hand-colored plate of the eastern American Blue Jay in Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida, etc., which he had seen years before in the library of the St. Petersburg Academy; and he identified Lepekhin’s find as its west coast cousin, known today as Cyanocitta stelleri, or Steller’s Jay. Now his last doubts about the land they had discovered were resolved. ‘This bird proved to me that we were really in America’” (Ford 1992/1966:80-2). The price paid by the expeditionary force for this discovery was considerable. Beset with difficulties, many crew members perished on the way home, including Bering himself. Steller lived only a few short years after returning to Russia, but left behind his scientific writings, which eventually found their way into print. His current renown hung more than once by the slenderest of hairs.

0 Comments

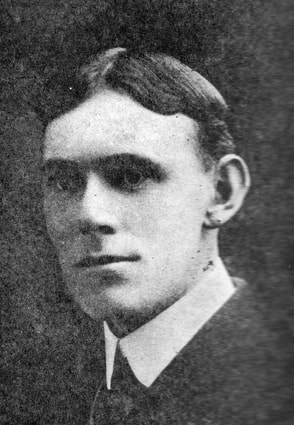

H. Forrest Moore, c1906 H. Forrest Moore, c1906 I come from a family of readers. Serious readers. People who read all the time. I am by far the slacker in the group. If my parents were alive today, I’m sure they would continue to read books despite all the electronic distractions available to them. My family members also distinguished themselves with skillful writing, although—aside from the two journals by father kept that are included in whole or in part in The Last Resort—I’m not aware that any of them ever wrote for pleasure or just for themselves. I have no recollection of anyone in my immediate family, say, writing poetry or short stories. It’s possible they did, but I’m not aware of it. And until this past summer, I wasn’t aware of another family member who had, as I did for many years, made a living as a writer or editor. My checkered career had me writing everything from technical manuals to marketing froth for private companies, higher education, and the Commonwealth of Kentucky. I spent countless hours reviewing, editing, and verifying pieces written by other staff members. My work days were dedicated to selecting just the right words to persuade, instruct, enlighten, or cajole a particular audience. But I now know about my Uncle Forrest. My great-uncle Hamilton Forrest Moore (1881-1972)—oldest son of the Rev. William Dudley Moore, brother of my grandmother Martha Florence Moore Goodlett—had a long career, I believe, with The Anderson News, the newspaper of my family’s home town, Lawrenceburg, Ky. My cousin Sandy recalls that Uncle Forrest continued to edit each edition of the newspaper and send his markup to the news office long after he had officially left his post. It appears that writing precisely, and scanning the work of others for errors, had become a passion for him, or perhaps a curse. I cannot read a newspaper or magazine or book without landing with a thud on every typo or missing word or poorly constructed sentence. For years I wanted to volunteer to copyedit my local newspaper the night before the rag was printed. It was an embarrassment. Now my husband has picked up the same habits. In fact, he sometimes catches outrageous errors that I miss. His keener mind makes him even better at it than I am. But I’m happy to know that somewhere in my genetic material there may be a tiny marker that I inherited from my Moore ancestors, the same marker that Uncle Forrest had. Because I lived outside Kentucky the first years of my life, I only remember meeting him once. He was quite old by then and I don’t have any specific recollections of what he was like. But I’m proud now to think that, long before I knew anything about how he had spent his life, I ended up carrying on the work he had loved.  Martha Moore Goodlett, Pud's mother, had a real phobia about having her picture taken. Her grandson Bob managed to snap this photo—with one of Pud’s hand-me-down cameras—after Bob started crying when his grandmother initially ran away from the camera. The tears did the trick. Photo circa 1960 in front of Bob’s family home in Franklin County, Kentucky. Martha Moore Goodlett, Pud's mother, had a real phobia about having her picture taken. Her grandson Bob managed to snap this photo—with one of Pud’s hand-me-down cameras—after Bob started crying when his grandmother initially ran away from the camera. The tears did the trick. Photo circa 1960 in front of Bob’s family home in Franklin County, Kentucky. Pud’s mother died two months after he did, in June 1967 at age 81. Her health, both physical and mental, had been failing, so the family tried to keep from her the fact that her youngest son had died unexpectedly. Whether we were successful or not, we’ll never know. Because I had lived in Baltimore until my father died, I never really knew my grandmother. I’m sure I was around her as a young child, but I have no recollection of having a conversation with her. I don’t remember her voice, her mannerisms, her interests. I do recall how surprised I was not too long ago when my cousin Mac described sitting with our grandmother and listening to baseball games on the radio. Evidently she was an avid fan. I had no idea. I don’t think I had ever really thought of her as a person with hobbies or passions or opinions. She was simply my grandmother, an abstract that I had shown little curiosity about fleshing out. Last week another cousin, Vince, sent us a copy of a note our grandmother had written to him in 1953. With just a few phrases, she came alive for me for the first time. It starts out, “Dear Vincy, Awfully sorry you didn’t get to come down Sunday. You must take your medicine real good and hustle yourself down before it gets too cold to play out.” She continues, “Mac has gone nuts over baseball and football. As cold as it was Sunday, he had his daddy out back playing ball with him. The little black pig has a room in the barn now right next door to the big pig. Kenneth’s big white rabbit is living in a coop nailed to the wall in the coal house. All fixed up for winter. “Mac had a jaw tooth filled yesterday. Didn’t whoop and holler nary a bit. Love, Mamoo” In that brief note, I learned how she spoke, what and whom she cared about, and what events preoccupied her thoughts, as well as a bit about the world she inhabited. As I hunker down to finish the novel about my maternal grandfather—a man who remained a mystery to everyone in my family until recent research unearthed the outlines of his remarkable life—I recognize even more urgently the importance of perfecting each character’s voice. A few words, an idiomatic usage, a turn-of-phrase paints a better portrait of the individual than countless overdone descriptions. What a character chooses to say, and how he mutters it, reveals his values, his circumstances, his background, and how he views himself and others in his world. Trying to bring my long-gone ancestors to life is a daunting undertaking. I make decisions daily about their language and their actions that may in no way reflect the reality of who they were. That is why I am writing fiction. But, this week, I learned a great deal from reading one brief note casually penned by another ancestor. Not only did I learn about her, but I learned how to be a better writer. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed