Lt. John C. Goodlett in Germany, 1946. Lt. John C. Goodlett in Germany, 1946. I’ve spent a good bit of time over the past two years reading about both World War I and World War II for two very different book projects. I have to confess, I’ve never been particularly interested in military history, but I have discovered, as many do, that it becomes fascinating when it’s filtered through the stories of family members. Unfortunately, I never had the chance to talk to either my father or my maternal grandfather about their experiences overseas. Of course, even if they had been around, it’s quite possible they would not have shared any information with me. That is true of many, many veterans. But I am glad that I now have at least a nominal understanding of where their service took them and what they faced. Although I missed honoring them publicly on Veterans Day November 11, I thought I could still write a few words before the month is out. Both men were sent to Europe near the end of their war, which meant both were in the midst of or in the vicinity of some of the most ferocious fighting. My father was an infantryman in Patton’s Third Army, one of the lieutenants who marched across Germany in spring 1945 and lived to tell about it. My grandfather was a radio operator in the Signal Corps during the first War, a replacement at the Meuse-Argonne offensive. The two wars—and the experiences of the Americans who served—were obviously very different. But the fact that two young men interrupted their lives and set aside their dreams to protect our freedoms and the interests of the United States is the same no matter the war, no matter the era. Today, every young man and woman who enlists makes the same sacrifice. Last week my cousin sent me a link to an interview conducted in 1980 that is part of The Witness to the Holocaust Project archived in the Special Collections of the Woodruff Library at Emory University. The man answering the questions is Captain John Henry Baker Jr., who commanded Company B of the 260th Infantry of the 65th Division of the Third Army. That was my father’s regiment, although I have not been able to confirm which company he was in. Captain Baker talks at length about his unit being one of the first to arrive at both Ohrdruf and Mauthausen concentration camps. If you have read The Last Resort, you have seen my father’s account of what he observed at one of these camps. (He does not name the camp in his letter home to his mother.) My father’s description and Captain Baker’s description align in nearly every grotesque detail. I did not have family exterminated at these camps. I cannot imagine the horror or the suffering of the imprisoned, although I have read Elie Wiesel’s account of his experience. But knowing that my own father witnessed the depravity of these camps first-hand makes me want to ensure that none of us ever forgets what happened there and why. Those who enlist to serve in our military deserve so much more than our respect, our support, our thanks. They most certainly deserve lifelong care for any physical, mental, or spiritual afflictions they bring home with them. But I have no idea how else to honor them—other than to continue to tell their stories.

0 Comments

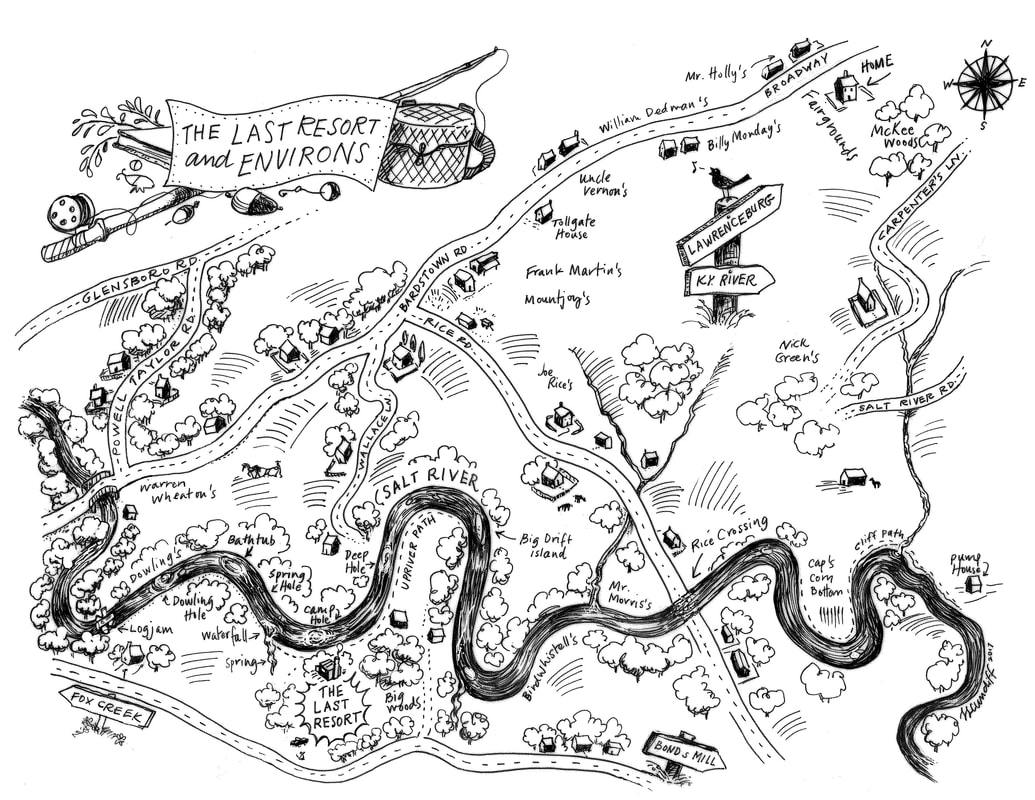

bell hooks described Crystal Wilkinson's "The Birds of Opulence" as a lyrical novel full of poetry. I highly recommend it. bell hooks described Crystal Wilkinson's "The Birds of Opulence" as a lyrical novel full of poetry. I highly recommend it. One of the undeniable joys of living in Central Kentucky is attending the annual Kentucky Book Fair. Each year the event, currently presented by the Kentucky Humanities Council, attracts well over 100 authors from across the commonwealth and the nation. The authors smile patiently as eager readers press up against their tables asking questions or bending their ears about topics they may or may not have much interest in. Many authors agree to give hour-long presentations about their books, the craft of writing, trends in literature, or their areas of expertise. The convention area is packed with readers, writers, and lovers of books. It is absolutely magical. Author and activist bell hooks, a Hopkinsville, Ky., native, was one of the featured authors this year. During her on-stage conversation with another Kentucky native, author Crystal Wilkinson, she talked about how, as a child, she had been transported by the poetry of Emily Dickinson. Sometime later, when hooks first saw a photo of Dickinson, she was shocked to learn that Dickinson was a white woman. She explained that she had never envisioned Dickinson as a person at all. In her young mind, no writers had physical embodiments: they were the words that spilled across the page, sprung from some mysterious ethereal source. When afforded the privilege of being in close physical proximity to a writer I cherish, I am immediately overcome with awkwardness. Somewhat like the young hooks, I imagine that writers exist in some illusory world outside our physical reality, beyond the clumsy clay feet of the rest of us. I have been attending the Book Fair for at least 25 years, but I have only recently had the nerve to actually approach any of the authors. I have typically been too awestruck to presume I could strike up a conversation with them. My husband, on the other hand, is completely comfortable wading right in. I remember watching in disbelief as he casually chatted with James Still or Bobbie Ann Mason. Like young bell, I consumed the words on the page but I could not fully imagine the embodiment of the human being behind those words, even when that person was standing right in front of me. I’m sure I got my reverence for books from my parents. I was lucky that way, but I didn’t completely understand that until I heard bell hooks and Crystal Wilkinson share stories of their disparate childhoods. While Wilkinson admitted that she had been a “spoiled only child” who was allowed to read voraciously as others in her family tended to the necessary chores, hooks, one of seven children, told the audience that her parents were skeptical of reading, fearful that it might plant unwelcome ideas in a child’s head. Her access to books was more restricted. The library at her segregated school, overseen by a white librarian, was not available to the children every day. The public library, however, became a refuge. She told a story of a neighbor alerting her that someone had just thrown away a collection of small leather-bound classics. bell promptly retrieved them from the garbage. My parents read all the time, so I learned to value books and newspapers at an early age. My sister and I received a book for Christmas every year. No matter what other shiny object might be under the tree, we knew we had to give the book the attention it was due. By the time my sister was a teenager, she had amassed an impressive library. I would sneak into her room and handle those books, awestruck by the variety and the sometimes bewildering titles. The Gulag Archipelago. The Bhagavad Gita. Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The Bell Jar. Reading is not a central activity of the boys spending time at The Last Resort. Although my father sometimes reports they spent the afternoon reading, he provides no specifics. The journal that he kept as an adult, however, which is excerpted in The Last Resort, includes detailed lists of his casual reading, which ranges from popular novels to biographies to Thoreau’s Walden to Ridpath’s history to Thurber’s humorous essays. That information alone gives you a clear understanding of the man. We are, after all, what we read. Today I am surrounded by books—on shelves, stacked neatly on nearly every horizontal surface, or piled on the floor beside me. I have purchased many of them at the Kentucky Book Fair. I confess that I have not yet read them all. But I love every last one. I find it nearly impossible to part with any of them. Sometime last year, I emailed my sister, describing the book clutter around my house and bemoaning the fact I never have enough time to read. She wrote back, “There's a Japanese word for that: tsundoku, the practice of accumulating books yet failing to read them.” She then shared a quote from John Updike: “Shelved rows of books warm and brighten the starkest room, and scattered single volumes reveal mental processes in progress—books in the act of consumption, abandoned but readily resumable, tomorrow or next year.” That was comforting. As I was leaving the Book Fair this year I was proud that I hadn’t spent hundreds of dollars, as I have sometimes in the past. Fewer than 24 hours later, however, I’m feeling both guilty and sad that I didn’t take advantage of the opportunity to purchase a few books that had actually been handled by the authors themselves. Another lesson learned. Although there is a common misconception that Kentuckians are ignorant and uneducated, we who are privileged to live here know that we have an extraordinary wealth of writers and philosophers in our midst. The Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington annually inducts writers into the Kentucky Writers Hall of Fame. The list of nationally recognized writers the committee has to choose from is long. And although recent efforts by the Carnegie Center to have Lexington named a UNESCO City of Literature failed, literary leaders across Central and Eastern Kentucky intend to apply again in 2019 (that is, unless President Trump withdraws the U.S. from UNESCO before that date). When bell hooks decided to return to Kentucky after spending many years away, her good friend Gloria Steinem was aghast. “But, bell,” she asked, “Who will be your friends?" hooks had no trouble finding a welcoming community of writers in Berea and across the commonwealth. Each year I can look around at the mass of people at the Kentucky Book Fair and smile. These are my people—the readers and the writers and the worshippers of the word. These are the people who keep me thinking and learning and growing. To all of the authors who spend a full day in Central Kentucky greeting their fans, to all of the readers who support the writers, I am immensely grateful.  Laura Lee Cundiff, artist and master sailboat renovator Laura Lee Cundiff, artist and master sailboat renovator As we were preparing The Last Resort for publication, I had one nagging frustration: I wanted to include a map of the area around the camp on Salt River, but I didn’t have the skills to realize my vision. I imagined a map that would help the reader locate Pud’s favorite fishing holes and river paths as well as the farms he and the other boys traipsed across to get to the camp. I had in mind something similar to the hand-drawn map of Port William at the back of Wendell Berry’s Jayber Crow. It was not until after we had published the paperback edition of the book that a friend suggested the perfect artist for the job. I couldn’t believe I hadn’t thought to contact her before. She is a friend of many years, a former work colleague, a recognized artist in multiple media, and a musician. As chance would have it, she was also another college chum of mine. Having her join our creative team—which already included college classmate David Hoefer, the author of the book’s introduction; Barbara Grinnell, my friend and former colleague at Transylvania University; and my husband, Rick Showalter—upped the talent level and increased my joy amidst all the hard work. Well, dear reader, you are in for a treat. This map is my small gift to you, to thank you for following this blog and sharing interest in this project. If you have read The Last Resort, I think you will appreciate Laura Lee Cundiff’s representation of “The Last Resort and Environs.” You will recognize most, if not all, of the landmarks on the map. Look closely and you will find Thomas the Model T pickup and Mike, Pud’s Wire Fox Terrier. Of course, all of the important fishing gear is in plain sight. If you do not yet own The Last Resort, you may want to purchase a copy of the new hard cover edition, which will include this fanciful map. Books will be available through your local bookseller by early December. (Simply ask the proprietor to order ISBN 978-0-9992540-1-1 through Ingram book distributors.) It would make a great Christmas gift!

As the season of thanksgiving approaches, I am so grateful for everyone who has helped bring this second release to fruition. Each time I dive into a new publishing project, I am amazed at the amount of labor involved. Thankfully, I have a supporting team that never lacks energy, inspiration, and encouragement. No matter how unreasonable my demands or how zany my requests, they have responded with patience and dedication. Who knows what the next chapter will be?  (Photo by Rick Showalter) (Photo by Rick Showalter) My husband and I had planned to be in Lawrenceburg Saturday to enjoy the Anderson County Art Trail and check in with those businesses downtown that are graciously selling The Last Resort (many thanks to The Mrs. Cox Shop and Tastefully Kentucky). Before we left home, however, we discovered that actor Matthew McConaughey was at the Wild Turkey distillery that morning to help volunteers distribute 4,500 Butterball turkeys to Lawrenceburg families. Now, McConaughey has been working with Wild Turkey as a spokesperson for a couple of years, so his appearance is not entirely a surprise. Nonetheless, Lawrenceburg is not always a traditional stop for celebrities who come to central Kentucky for horse races or movie filming. (OK, we have to cite the exception: the filming of George C. Scott’s “The Flim-Flam Man” in downtown Lawrenceburg before its 1967 release.) By the time we got downtown, everyone was abuzz with excitement. The streets were packed and every parking space was filled. McConaughey had made a favorable impression among townspeople as a friendly and generous individual. Bourbon distilling has been a critical driver of the Lawrenceburg economy since the mid-1800s, in part because of plentiful water sources from the Salt and Kentucky Rivers and the natural filtration of the limestone rock in the area. An Irish immigrant opened Ripy Brothers distillery at the current site of Wild Turkey, high above the Kentucky River east of Lawrenceburg, in 1869. Before Prohibition, Anderson County was the home of more than a dozen distilleries. By the 1940s, however, two stalwarts had survived: Ripy Brothers, now Wild Turkey, and Old Joe’s, currently Four Roses. Pud mentions both in The Last Resort. As a nod to this rich local history, the parent company of Wild Turkey, Campari, recently announced plans to reintroduce two pre-Prohibition brands of bourbon as part of its Whiskey Barons Collection: Bond & Lillard and Old Ripy. (These were very limited releases and may no longer be available at retail outlets.) The company is making every effort to replicate the original Old Ripy recipe, under the watchful eye of Ripy family descendants. A portion of the proceeds will go toward the ongoing restoration of the majestic T.B. Ripy home, originally built in the 1880s on South Main Street in Lawrenceburg. Pud’s buddy Bobby Cole was a descendant of the Bond family that produced the Bond & Lillard brand, which won the Grand Prize at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. Campari is using the judges’ tasting notes from the World’s Fair to develop the new recipe. The Bonds had been distilling bourbon in Anderson County since 1820. Today, the Bourbon Trail brings thousands of tourists to Kentucky each year, and the various distilleries vie to build the most accommodating visitors center and offer the most appealing small batch bourbons. Certainly the Anderson County distilleries are no exception. Pud and Mary Marrs enjoyed drinking Kentucky bourbon and introducing it to their friends across the country during a time when bourbon did not have the high profile it does today. I have to think they would be delighted to know that Hollywood celebrities are helping bourbon distilleries attract new customers and invigorate their hometown community. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed