Yard signs in Louisville, Ky., October 31, 2022. Photo by Joe Ford. Yard signs in Louisville, Ky., October 31, 2022. Photo by Joe Ford. Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., offers some suggestions for the upcoming election. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. If you live in Kentucky, it’s time for our second spring—time to let your lawn sprout political signs! If you’re unsure about what varieties to cultivate, here are a couple of ideas: U.S. SenatorCharles Booker is a native Kentucky species, supportive of diversity and other species in our yards, well-adapted to our growing zone, enhancing the soil to support healthy growth of all plants, and displaying something of interest in all seasons. Rand Paul is an invasive species destructive to our lawns and crowding out our wide variety of native plants, which have little natural resistance to his bullying tactics that spread out-of-control suckers all over the property, threatening indigenous vegetation. Choice: Charles Booker. Amendment 2Yes is a noxious and poisonous cultivar, aggressive and mean. It is a variety bred by dogmatic politicians (mostly male) in Frankfort and Washington whose goal is to dominate smaller, weaker plants and weed out any that don’t reproduce exactly as they think they should. No recognizes the place each plant has in a diverse environment and its need for support and care during all seasons. With the help of a concerned gardener, each plant will thrive in its own space, in its own time. Choice: No Those are the two hot topics around here. Perhaps you have an opinion on your local plantings.

But seriously, put some signs out. Especially for those living out in the state, a sign or two may allow others to think, “Gee, someone else supports the positions I do. I am not awash in a sea of hopelessness and small thinking.” Do vote.

7 Comments

Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, affirms her faith at a common gathering spot. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. In the midst of the chaos, I pause to celebrate the wonder of the local farmer’s market. Most communities have one. I am fortunate to have a handful to choose from. Two set up shop less than three miles from my house weekly—one on Sunday mornings and one on Wednesday evenings—so I am quite blessed in this department. When I need a dose of hope for humanity, the farmer’s market always serves it up bountifully. Here my neighbors and I can meet the people who plant the seeds, till the soil, pull the weeds, and harvest the produce they pack up each week to haul to the market where we share small talk and smiles as I make my selections. Nature shows off her miraculous skill of generating prolific amounts of food from tiny seeds in the rainbow array of kale, carrots, sweet potatoes, okra, eggplant, lettuces, beets, cucumbers, green beans, melons, tomatoes, peaches, and more filling the market tables. I stop in front of the fresh flower vendor’s booth as my eyes roam the bouquets in awe and I silently praise Mother Nature for providing this kaleidoscope of arrangements I can choose from to take home and call my own. Of course, the vendor uses her talents to pull together the perfect combination of colorful blooms to complement one another, but the good green Earth provided her the palette to begin with. Other farmers may offer freshly laid eggs from the feathery hens they feed, house, and tend on their farms, or meat from the livestock they sustain. Still others put out honey, jams, or products made from the raw ingredients their farms provide. Some even cook up freshly made foods we can enjoy gobbling up on the spot. The world just seems righter when I can buy my food directly from the people who facilitated the growth and harvest of it. I can transact business with no one in the middle—just my dollars going straight to the good people that did the work to get it to my hands. Now, I could be biased because I grew up on a farm and, often, we had a garden full of tomatoes, sweet corn, sometimes watermelons, potatoes, green beans, or carrots. I remember gardening as a chore that brought me no pleasure whatsoever. But boy did I love consuming the deliciousness from my own back yard. Nothing matches sinking my teeth into the shiny plump kernels on an ear of steaming sweet corn, slathered in butter, on a hot July evening, or a juicy mouthful of perfectly ripened tomato still warm from the summer heat, sliced generously, and sprinkled with salt and pepper. Moving to the suburbs of Atlanta as an adult, I tried to recapture a bit of that delight by planting strawberries, raspberries, and blackberries in my back yard. I had to rig up some netting so the incredibly entitled birds would not consume *all* the berries before I got to them, but it was worth the hassle. I experienced a unique type of joy when picking berries off the bushes around my home and popping their sun-warmed succulence directly in my mouth. There is much trouble around us, and yet so much goodness, too. A trip to the farmer’s market reminds me of that. I can chat face-to-face with my local food producers. I’m supporting the local economy and a well-balanced diet. And I’m also boosting my faith that various members of the human race can coexist in peace and harmony, with respectful give and take, just as the farmers do with their land and livestock, and as we all do in the microcosm of the market. At this moment in time, I need as many reminders of that possibility as I can find.  Pink lady’s slipper in the Red River Gorge. Photo by Olive Ford. Pink lady’s slipper in the Red River Gorge. Photo by Olive Ford. Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., responds to Reunion on the Rocks with some reflections of his own. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. It occurs to me that I spent my winter in three pursuits: 1. Contemplating, from an evolutionary standpoint, why my hair is migrating from the top of my head to my ears and nose. What’s up with that? 2. Worrying about spontaneous human combustion. It’s a thing, apparently. 3. Hmmm… ummm… wait, wait… uh, oh darn, I can’t remember. It will come back to me. Sallie’s recent post reminded me that, instead, I could have been stumbling along the trails in the Red River Gorge and adjacent Clifty Wilderness. My family has spent a lot of time there camping in the milder months, mostly at Koomer Ridge or Whittleton. In the winter we retreated to the cabins at Natural Bridge, snuggling up before the fireplace after a winter hike. Derby weekend was our favorite time to head to the hills: no school activities, no violin recitals, no social requirements. It was easy for us to get away, as it was for my daughter’s friends and their families who followed us down. Everyone brought something for communal use. Pity the newcomers who signed up to bring cups. You have not seen indecision until you’ve seen a newly environmentally conscious parent standing in Kroger trying to decide between the red plastic cups and the Styrofoam cups. (Will the other parents judge me? Will the kids ostracize my child? Where the hell are those tiny little paper Dixie cups?) Soon they would learn, as we had: bring all your mugs from home and take them back with you. Once a family from India was assigned to bring the makings of s’mores. You know, graham crackers, Hershey bars, marshmallows. Delivered as ordered: graham animal crackers, mini-bite Hershey bars, and tiny hot chocolate marshmallows. Derby weekend was also a perfect time to be in the woods: the wildflowers were out in droves, and our favorite trails sheltered their treasured jack-in-the-pulpits and pink lady slippers. And if you saw a yellow one, well, the angels must have noticed what a bad week you’d had. Perhaps Jim and Jeff and Sallie and Greg and Walter and Bob and Bob would let me tag along. I hope to have more time soon. As you may have surmised from my enumerated winter pursuits above, I am sort of on a glide path to retirement. Not quite 65, but I recently quit my long-time corporate jobs and took a pay cut to help with a small business run by my brother as he brought it out of the pandemic shutdown. For those readers contemplating a similar move, let me counsel you to learn from my mistakes (revealed in that little paragraph above). I am not a math or accounting major, so it took me by surprise when the seemingly innocuous idea of accepting a salary cut turned into less money actually being deposited in my bank account each week. I mean, who knew? So when I finally, gulp, step down to zero income and full retirement, maybe I can hike with you guys. I expect I’ll be feeling lost and confused. You, the experienced hikers and retirees, can nudge me in the right direction, down the trail and on through the next stage of life.  Jim and Bob McWilliams rest on the way back from Hanson’s Point in Wolfe County, Ky., November 9, 2021. Jim and Bob McWilliams rest on the way back from Hanson’s Point in Wolfe County, Ky., November 9, 2021. When I graduated from Anderson County High School in 1977, I intended to leave Lawrenceburg (Ky.) behind and never look back. I didn’t want to attend the actual graduation ceremony, but my mother made me. I refused to get a new dress (to wear under the gown?) or the required white sandals (when would I ever wear those again?). So, over and over, I clopped across the stage in that hot high school gym wearing my worn Dr. Scholl’s, the rubber long gone from the bottom of the wooden footbed, as I was unexpectedly called to accept a number of awards. My mother was mortified. She told me later that she overheard people around her whispering, “That poor little girl. Her family obviously couldn’t afford a new pair of shoes. Isn’t it wonderful that she’s receiving these scholarships?” Afterwards, backstage, I remember looking around at my classmates as they hugged and cried and laughed. I felt nothing. No one approached me and I didn’t see anyone I wanted to say goodbye to. It all seemed completely hollow. I just wanted to get home and get on with my life. Eventually, I did go back, of course, but it took me nearly 40 years. When David Hoefer and I started compiling The Last Resort, I spent a lot of time around Anderson County imagining the area in the 1940s, visiting my dad’s old camp on Salt River, and talking to the few people who still remembered him. I brought a different perspective this time, and a purpose. I was interested—fascinated, as it turned out—by my family’s long history in the area, which I had long ignored. And then this winter, by another stroke of sublime serendipity—or perhaps cosmic payback—I’ve found myself thrown together with a motley group of boys who also graduated from Anderson County High School in the 1970s. I suppose it started with our pilgrimage to Panther Rock in November 2020. My cousin Jim McWilliams had been told I knew the owner of the property and could get us access. When Jim contacted me, he mentioned that he and his friend (and my former classmate) Jeff Lee wanted to revisit a site they had hiked many times as youngsters. The three of us soon realized we were always up for a walk in the woods. When Jim and Jeff began to hike the Red River Gorge area with friends Greg Hood and Walter Moffett this past fall, I somehow wheedled an invitation to tag along. Others have joined us at times: my cousin Bob McWilliams; another classmate, Bob Cox; another of Jim’s classmates whom I knew from band, Kelly Rose; Barry Puhr, son of one of my mother’s good friends. All Anderson County graduates. All fellas I either knew or knew about when I was in school. All with completely different life histories and distinct talents. All now joined together, decades later, by our love of being in the woods. At the end of my high school years, I looked around and thought I had nothing in common with the people surrounding me. I had no idea how to talk to them. I had never felt that I fit in. And now, 45 years later, I eagerly look forward to spending time with this gang of intrepid trekkers. Our careers are behind us. We’ve set aside our professional personas and the roles we played for decades to meet society’s demands. Now we’re just a group of comrades who can’t wait to get back on the trail.  Photo by Rick Showalter. Photo by Rick Showalter. Tornadoes. Floods. Mud slides. Ice storms. Kentucky has endured its share of catastrophic weather in the past two months. This week, it was Winter Storm Landon striking some of the same areas of Western Kentucky devastated by the December 10 tornadoes and then moving into north central Kentucky. Throughout the commonwealth, homeowners prepared for potential widespread and lengthy power outages. Many of us had flashbacks to 2009 when a devastating ice storm left more than half a million Kentucky homes and businesses without power for a week or more. Thankfully, Landon didn’t land quite the same punch. Here in Scott County we were, once again, largely spared. We spent a day waiting for the ice to accumulate and the lights to flicker, but by nightfall we were beginning to breathe a little easier. Snow and a bitter wind continued into the next day as temperatures dropped into the teens. And then, late this afternoon, the sun came out. I pulled on some warm clothes and headed out with the dog. I walked to the top of the hill…and found myself in a magical crystal kingdom. The sun was backlighting the patches of woodland trees that dot the neighborhood, each limb and twig still fully encased in ice. The reflected light was blinding. Prismatic color—pink, green, yellow, blue—sparkled and bounced in a happy jig. It seemed someone had draped the trees with thousands of the tiniest twinkling Christmas lights. A photo couldn’t do it justice, and it saddens me that I couldn’t find a way to share it with you other than through my feeble words. It has already been a challenging winter. Record-breaking storms have battered numerous areas of the country. The omicron variant has sent many of us back to our safe rooms. Friends and relatives have lost loved ones—too many loved ones. I fear what the rest of the year has to offer. But, for an hour, Lucy and I walked amid the sparkling trees beneath the blue sky, completely enraptured by the scene around us. These are the moments I will pocket for now and pull out when I need reassurance of better days ahead. Scenes from winter storm landonWinter Storm Kenan January 28, 2022The piercing shriek launched me from my position reclining on the sofa. I had landed there moments before after relinquishing my spot in the bed to my elderly dog, her whole body shaking in distress from the thunder and lightning and pounding rain. Was it the smoke alarm? I sniffed. No detectable smoke. I stumbled toward the sound. My cell phone was on the kitchen table, practically bouncing from the urgency of its alert. “Tornado Warning,” I saw on the screen. The phone rang—an old-fashioned ring from a land line—and when I picked up the receiver, I heard this simple message: “Tornado warning. Take cover.” I raced back to the living room, just as the siren near the front of our neighborhood began to wail. I turned on the TV to a local channel and heard, “The possible tornado is directly over the city of Frankfort heading toward northern Scott County.” That’s where I live.

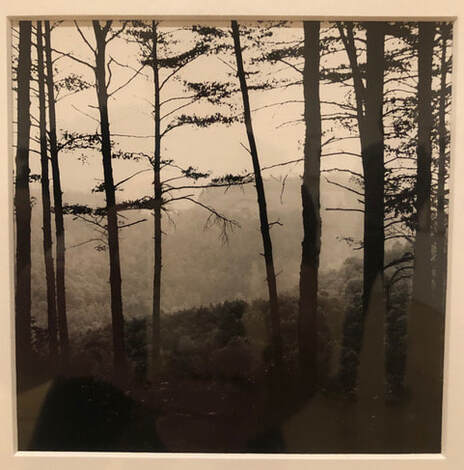

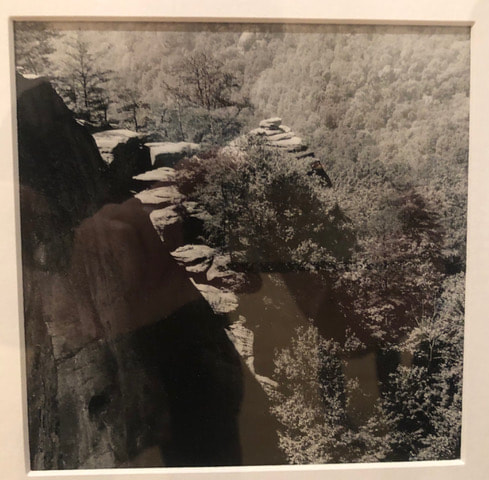

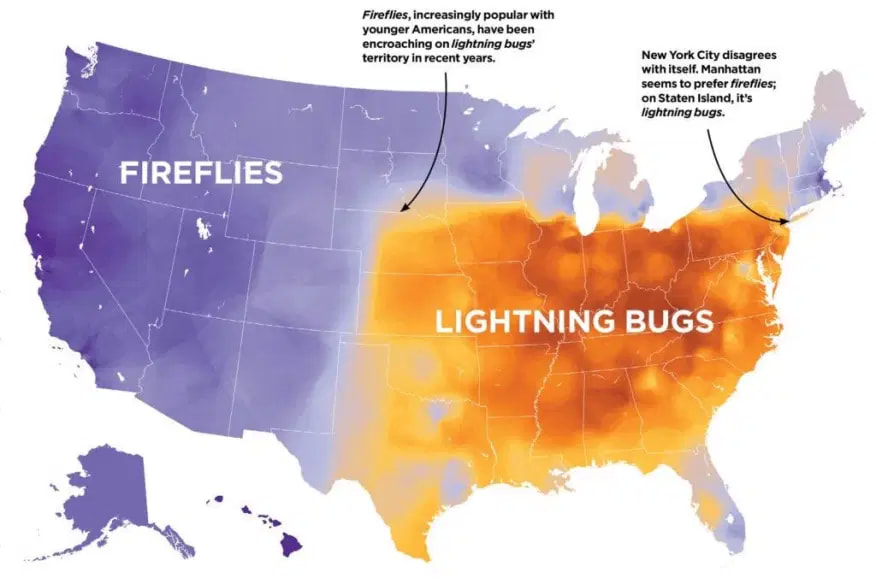

I called out to Rick that we had to go to the basement. I dragged Lucy down the stairs and into the interior bathroom, grabbing my cell phone and a flashlight as I went. I turned up the TV in the basement to hear the reports and kept the bathroom door ajar. I heard Chris Bailey of WKYT say, “If you have a helmet—a batting helmet, a bicycle helmet, anything—put it on. Protect your head.” I made a mental note to store those old bike helmets in the bathroom. Then, “The suspected tornado is moving toward Peak’s Mill on its way toward Stamping Ground and Sadieville.” We were directly in its path. I watched the radar on my cell phone. The storm was moving fast. In a matter of minutes, it appeared the worst of it was skirting the northern edge of our neighborhood. And then it was gone. We escaped again. Although Stamping Ground, a small community in western Scott County, had suffered extensive damage from a smaller EF1 tornado just five days earlier, no other nearby areas were significantly affected by this storm. It was not until early Saturday morning, when I turned on the news, that I had any idea of the extent of the devastation to Kentucky and surrounding states. It’s almost a cliché, but tornadoes in particular make you wonder why you, your loved ones, your home were spared when others lost everything. In communities like Bowling Green, where the tornado made a more traditional swath of destruction, news images show one house demolished and the one across the street still standing, relatively unharmed. In Mayfield, unfortunately, there seem to be few random “lucky ones.” The storm appears to have annihilated most of the town. Many lives have been lost. As I type this, families are still searching. The grief and horror are immeasurable. The trauma to these communities will endure. The costs to rebuild will swell. Yet back in Scott County, the sun is shining and the sky is a brilliant blue. The crisp air invites you outdoors. The winds are finally calm. It’s hard to reconcile this pristine day with what I know has happened a couple hundred miles west. I’ll save my screed on climate change for another day. Today we are all thinking of those affected by these storms. Today, once again, I am wondering why my life has been left intact, as the wheel of fate continues to turn.  Photograph by Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925–1972) from “The Unforeseen Wilderness,” 1967–1971, as currently exhibited at the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Ky. ©The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Images of exhibited artwork captured by David Hoefer. Photograph by Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925–1972) from “The Unforeseen Wilderness,” 1967–1971, as currently exhibited at the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Ky. ©The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Images of exhibited artwork captured by David Hoefer. David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, reminds us of the power of art. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the emergence of environmentalism as a significant element in the political wrangling of the day. Kentucky old-timers likely remember one of the pivotal episodes in that emergence: the battle over damming the Red River and what would have been the wholesale alterations to landscape and ecology resulting from infrastructure of that magnitude. The Army Corp of Engineers and many local residents lined up on one side; the Sierra Club, environmentalists, and various culture warriors lined up on the other. Each alliance had serious points in its favor. Ultimately, with the scrapping of construction plans, the environmentalists won out. The gorge is now protected by inclusion in federal programs for natural, historic, and archaeological settings. I bring this up because the J. B. Speed Art Museum in Louisville is currently hosting an exhibit that was directly inspired by the battle over Red River Gorge. One of the dam’s chief opponents was Kentucky author Wendell Berry. Berry coauthored a book, The Unforeseen Wilderness, with another native artist, the Lexington photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard. It is Meatyard’s photographs from this collaboration that are on display, and which allow us to reenter that time and place in history. The Unforeseen Wilderness is undoubtedly the most important document for the defense of the ecological and spiritual qualities of a unique landscape to emerge from the conflict. (I suppose the other side could point to the dam’s architectural plans and, no, I’m not being facetious. Good engineering is to be admired.) Meatyard and Berry worked separately and together to produce their dual vision for preserving the gorge. Berry uses words, so he carries the weight of argument, which is sometimes cranky and polemical. Meatyard uses shadow and light, which means that he comes closer to presenting the gorge as it is, or was, within the limitations of photographic technology and one man’s subjective response to the world in front of him. The great variety of settings at Red River, the many microclimates and eco-niches, becomes immediately apparent in Meatyard’s camerawork, which is amply attested to in the book and the exhibit. That diversity bounding on the infinite may be the best case for leaving the flood-prone gorge in its (more or less) natural state. My wife and I noted the darkness of many of the photographs. Some of this was attributable to museum lighting, but the darkness was also a conscious decision by the artist, either in camera settings or darkroom procedure (or both). Berry addresses this facet of Meatyard’s work in his foreword to a revised and expanded edition of The Unforeseen Wilderness, published after the photographer’s death from cancer: “As I look now at [Meatyard’s] Red River photographs, I am impressed as never before by their darkness. In some of the pictures this darkness is conventional enough. It is shadow thrown by light; we see the lighted tree or stone and we see its cast shadow. In other pictures the darkness is not shadow at all. It is the darkness that precedes light and somehow includes it; it is the darkness of elemental mystery, the original condition in which light occurs…The darkness of these pictures is an imagined darkness; and this was a courageous imagining, for the darkness is made absolute in order to make visible the smallest lights, the least shinings and reflections. Sometimes the lights require hard looking to be seen” (1991:xi-xii). Here we’re edging into the metaphysical. Maybe Meatyard’s Red River Gorge is more art than nature after all. The Meatyard exhibit is showing at the Speed until February 13, 2022. I’ve included a few photographs of the photographs as enticement. (Just think about how much better the originals will be in person.) Click here for more information on this intriguing backward look to the early days of the environmental wars.  At the summit of the Teeter-Totter Trail. Photos by Rick Showalter. At the summit of the Teeter-Totter Trail. Photos by Rick Showalter. Last Sunday, on yet another unusually cool morning, we decided to take Lucy for a walk at a nearby network of mountain bike trails appropriately called Skullbuster. Rather than staying on the abandoned roadbed as we typically do, we donned hiking pants in a vain effort to ward off ticks and chiggers and headed for the orange trail, a byzantine loop of crisscrossing singletrack that features behemoth oak and maple trees as well as the old Stockdell family cemetery. At one crossroads we decided to check out the Teeter-Totter Trail. I initially imagined the name referred to an undulating path with sharp up and downhill sections. Instead, it turned out to be a gradual uphill through both pastoral woodland and some slightly more open brushy areas. At one point we passed an old stone wall, evidence of a former homestead, which currently serves neither as property line nor rudimentary enclosure. A few yards farther up, at the highest point on the trail, we arrived at a small clearing where a simple bench had been erected among the towering trees. A few steps beyond the clearing were…two teeter-totters. I had not expected that the trail would lead me—literally—to teeter-totters or, as I always called them, seesaws. It was a moment of pure surprise and delight. They appeared rough-hewn but sturdy enough for two adults, so Rick and I tried them out. Lucy was quickly bored, so we took the intersecting path to Wyatt’s World, a trail full of laid stone ramps and log jumps to challenge the cyclists, and eventually found ourselves back on a familiar stretch of the orange trail. As we walked, I thought about how those teeter-totters had gotten there. Remembering the stone wall, I imagined a family in the early twentieth century constructing them to entertain a passel of children. That idea had evidently settled in my mind when Rick mentioned that just as Wyatt’s World was likely named after a central Kentucky cyclist with a penchant for treacherous downhills, he suspected a cyclist named Teeter had been inspired to construct the teeter-totters from leftover lumber as he worked with other volunteers to develop the trail system. His comment startled me. We had both stumbled upon the teeter-totters for the first time just moments earlier and, in that brief period, we had both quietly come to radically different conclusions about how they got there. My romantic mythology arose from my limited understanding of the history of the place, which I had concocted purely from the scant evidence left behind by long ago inhabitants. In my silent musings, those who built the trail system had happened upon a relic of another world. Seeing the same evidence, Rick concluded quite sensibly that those constructing the trail simply hadn’t wanted to lug unused lumber back down the trail and had had imagination sufficient to figure out an entertaining application for it. If a conversation hadn’t ensued, we would have left the trail carrying two immensely different interpretations of this site of human activity. I look to my friends with backgrounds in archaeology or anthropology to explain the human frailty this experience reveals. I will admit it has humbled me. Although I was still embellishing my romantic vision of farm children running toward the teeter-totters after a day of chores, I can imagine how quickly that initial vision might have congealed into “fact.” Can my experience, my understanding of what I observe, my conclusions be so errant from what may actually be true? How quickly I could have gotten to certainty—and been dead wrong. At that moment I realized how easy it is to create our own mythologies. And once we have created them, we are emotionally bound to them. We will not give them up easily. After listening to Rick’s unexpected interpretation of what we saw, I felt fairly quickly that his scenario was probably more likely than mine. But if my vision had had more time to gel, I might have been more stubborn. He might not have been able to change my mind, and I might have fought tooth and nail to defend the mythology I had created. I could imagine myself insisting on the validity of a baseless story I had simply told myself over and over. Perhaps this experience not only provided a much needed dose of humility. Perhaps it also provided a window into the empathy I currently lack to understand those who seem to have fallen under the spell of what I believe to be false interpretations of facts or experiences. I may never share their beliefs, but perhaps, if I were willing to set aside my own contrariness, I can better understand how they came under the sway of a mythology they so dearly want to believe.  The creature in question. (Well, one of many: there are actually thousands of firefly species. Or lightning-bug species. Or whatever.) The creature in question. (Well, one of many: there are actually thousands of firefly species. Or lightning-bug species. Or whatever.) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, explores our relationship with a beloved emblem of summer. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. They dot warm summer nights like phosphorescent punctuation marks. They carry bioluminescent chemicals in their abdomens that produce a cold light, more like LEDs than Edison incandescents, to attract potential mates. Little children (and adults behaving like little children) enjoy chasing after them, catching them in hand and watching them glow on release. (I’ve been known to do this after a couple of beers.) What am I talking about? Lightning bugs, of course. Or fireflies. Or glow worms. Well, which is it? It turns out that it’s all three, though the first two names are now more common than the third. But it also turns out that what you call these creatures is, in part, dependent on the section of the country from which you hail. The following map recently appeared in an article on the Rochesterfirst.com Web site: This makes sense to me. I’ve called these beetles both names at different times but lean toward lightning bug. No surprise there, as Kentucky is smack dab at the center of lightning-bug territory. But I grew up in North Syracuse, New York, at the northern edge of the same region, and called them lightning bugs up there, too.

The article goes on to note an interesting coincidence. Firefly is more common in parts of the country that record more wildfires. Lightning bug is more typical of areas with higher frequency lightning strikes. The author correctly states that this is not proof of causation. But it is definitely intriguing. We get no help from John Goodlett on this topic. The bugs are never mentioned in The Last Resort. (Pud always was a plant guy, first and foremost.) What to call an insect may seem like a purely academic question, of little import to anyone other than linguists or entomologists. That notion would be mistaken, however. Sectional differences are an integral part of American history, with serious and sometimes dire consequences. These many differences—a true, organic form of diversity rather than the often forced and phony stuff that we’re being inundated with now—are gradually being rung out of our lives by the growing homogeneity of corporate-state culture. I like lightning bug but am okay with firefly as well. I hope distinctions like this one, and thousands of others, stick around for a while longer.  Flowers hover above a cloud of green at the Walter Bradley Park in Midway, Ky. Photos by Rick Showalter. Flowers hover above a cloud of green at the Walter Bradley Park in Midway, Ky. Photos by Rick Showalter. I live in the fastest growing county in Kentucky. It seems that everywhere I go I come face-to-face with this reality: farmland bulldozed for a new subdivision, woodlands daylighted without a thought of what has been sacrificed, trees pushed into hulking piles of smoking debris, traffic and impatient drivers clogging the roadways, new interstate exits and newly built intersections designed to handle today’s volume of cars. New schools, new businesses, and a new bypass to get around it all. And let’s not forget a controversial dump still accepting garbage way beyond its approved capacity. This morning, however, we took a road trip a few miles southwest to Woodford County, where the tiny town of Midway is trying desperately to manage its own growth. It has been called “Kentucky’s Mayberry,” and as little as ten years ago it was a quaint little hamlet of historic homes and a bustling main street that attracted visitors to its special collection of unique restaurants and art shops. In recent years, however, industry has come to the area near the interstate, along with fast food franchises and convenience stores. It’s a disheartening trend that I expect is nearly inescapable for every community that had been temporarily left behind by the ravages of what many call progress. But just off Midway’s historic downtown Railroad Street, the town has established the remarkable Walter Bradley Park, named for a town native and World War II Army veteran who, in 1977, became the first African American on the Midway City Council. He served the community in that capacity for 24 years. I had been on the periphery of this 28-acre park many times for events, mostly races where I was more focused on making it to the start line on time and finding the finish line while still breathing. This morning we could wander the grounds and its four miles of walking trails at our leisure. Unlike many city parks, this is not simply a mowed area with a few signs and perhaps a walking path. Some visionary arborists and gardeners have created a verdant sanctuary that delights all the senses. On an unusually cool summer morning, the butterfly gardens were bursting with color. A wide variety of native trees—some old, many recently planted—welcomed us, already offering shade and guaranteeing a cool summer retreat in the years to come. Gravel paths wend among the gardens, around Sara Porter’s Seed Farm shed, across wooden footbridges, past an old spring, circling near horses grazing in the nearby meadows, and winding up to the public pavilions behind the elementary school. As I stepped into the long arbor facing one of the many wildflower gardens, I felt as if I had stepped back into another century. Time slowed. Natural beauty again felt revered. I could imagine spending a full afternoon seated on the benches watching the birds and butterflies while engaged in idle conversation. Would I be twirling a parasol? The good people of Midway have always seemed to understand the importance of their community’s history and have managed to preserve its rare qualities. This battle will intensify over the next few years. But they have committed to nurturing an oasis in their midst. Bravo. Central Kentuckians now have yet one more reason to visit. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed