|

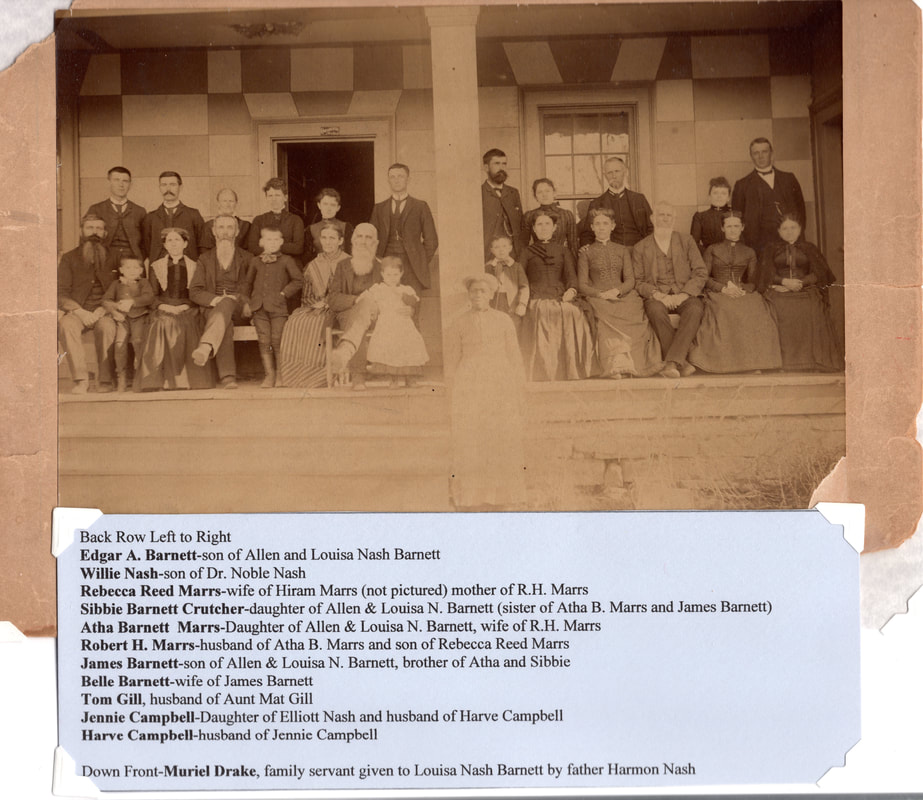

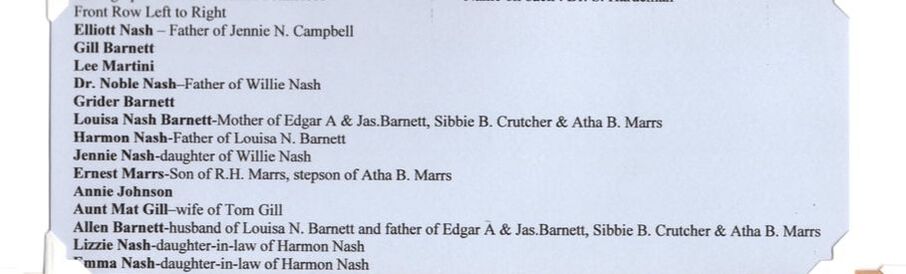

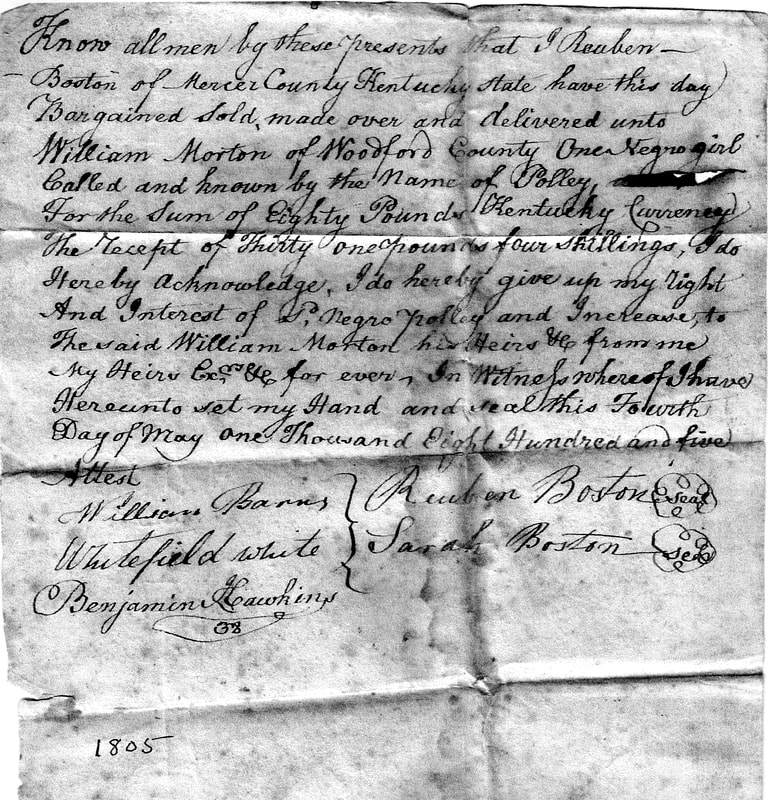

When I was in second grade, I vividly remember coming home and declaring to my mother that I intended to marry my classmate David Oldham. He was handsome, smart, and debonair (or at least that’s how I recall him more than 50 years later). My mother frowned. Always the pragmatist, never the romantic, she said, “But you can’t marry David, Sallie. He’s colored.” I was outraged. I was defiant. I thought my mother was just trying to deny me the wedded bliss that I imagined. But it was Baltimore in 1966. Loving v. Virginia wouldn’t be decided until 1967. Mother knew best. The following spring I watched as the city bused black children from their inner-city homes to P.S. 212, my school in northeast Baltimore. Even at seven years old I could feel their terror. They couldn’t sit comfortably in their seats. Their wide eyes darted around the room. They didn’t speak. I was gone shortly after that—before the end of the school year and before the Baltimore riots—whisked away to my own foreign world in Kentucky. I did not go easily. I hid in my bedroom closet, hoping my mother would leave me behind so I could stay near my friends. These memories have come back recently as the nation has flirted with another conversation about busing. We’re talking again about reparations. And this month we’re acknowledging the 400th anniversary of the first African slaves being brought to our shores. As I’ve dug into my family history over the past few years, I’ve discovered evidence that the ancestors of at least three of my four grandparents owned slaves. They all lived in Kentucky or Virginia or Tennessee. Most of the families had come to this land from Great Britain well before we had gained our independence. I don’t know that any of my ancestors were sizable landowners, but they evidently elected to use slave labor to keep the household or small farm running. At first, I was shocked. Then I felt resigned. Those of us whose families have been here longest may have the most to explain. While everyone in this country benefited from slave labor, we are the ones who claimed ownership of other human beings. We are the ones who were here to grumble and complain as each new ethnic group came to this country fleeing famine or religious persecution or genocide. Or arrived here simply seeking a better life. Today we malign the immigrants who knock on our door looking for refuge, for work, for a future. We blame the ills of this country on the “huddled masses” who come here seeking hope, while we quietly benefit from the work only they are willing to do. But perhaps it’s not recent immigrants, but those of us whose ancestors arrived here earliest who carry the biggest burden. We’re the ones who now need to demonstrate what we can offer this country. How we can make it whole. How we can repay the gifts we’ve received. That’s our public charge.

1 Comment

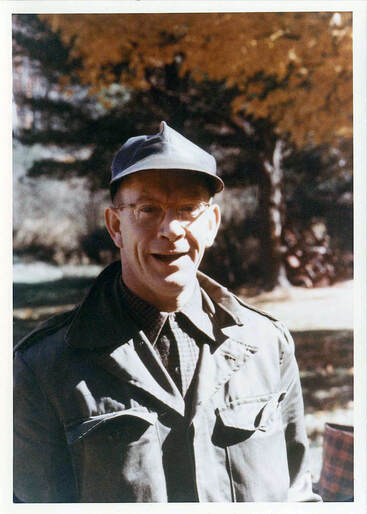

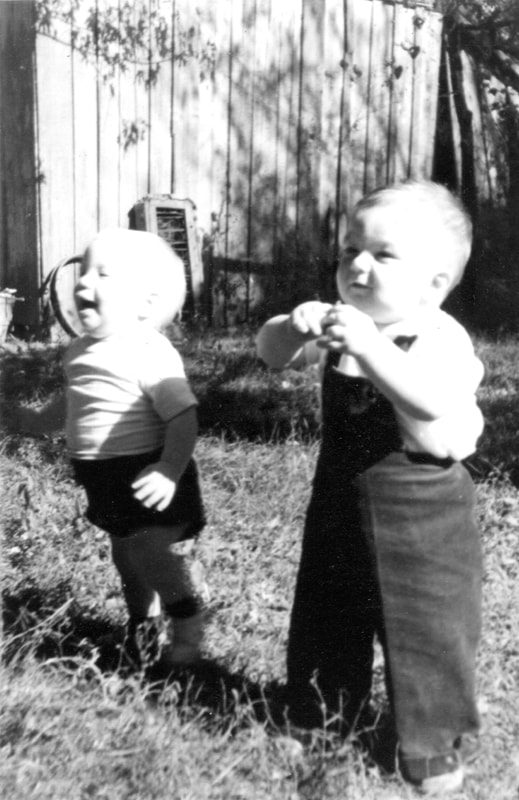

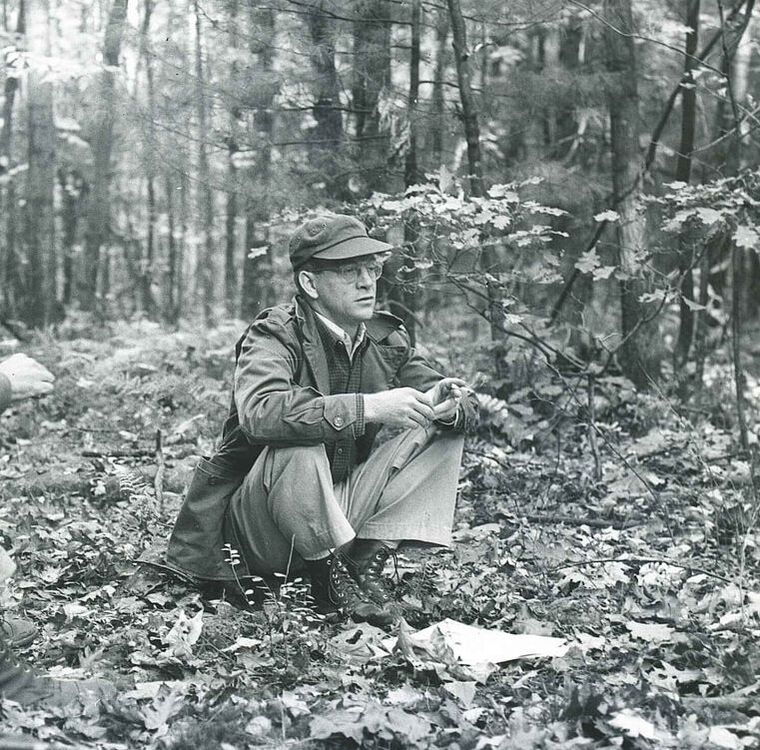

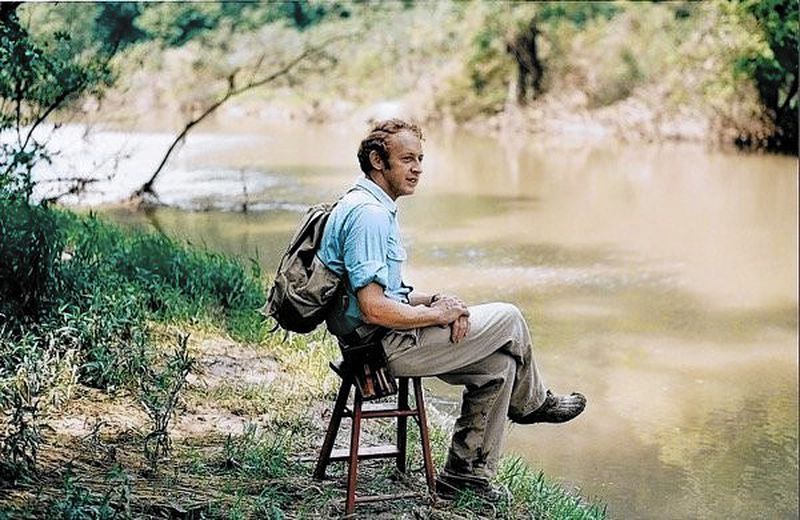

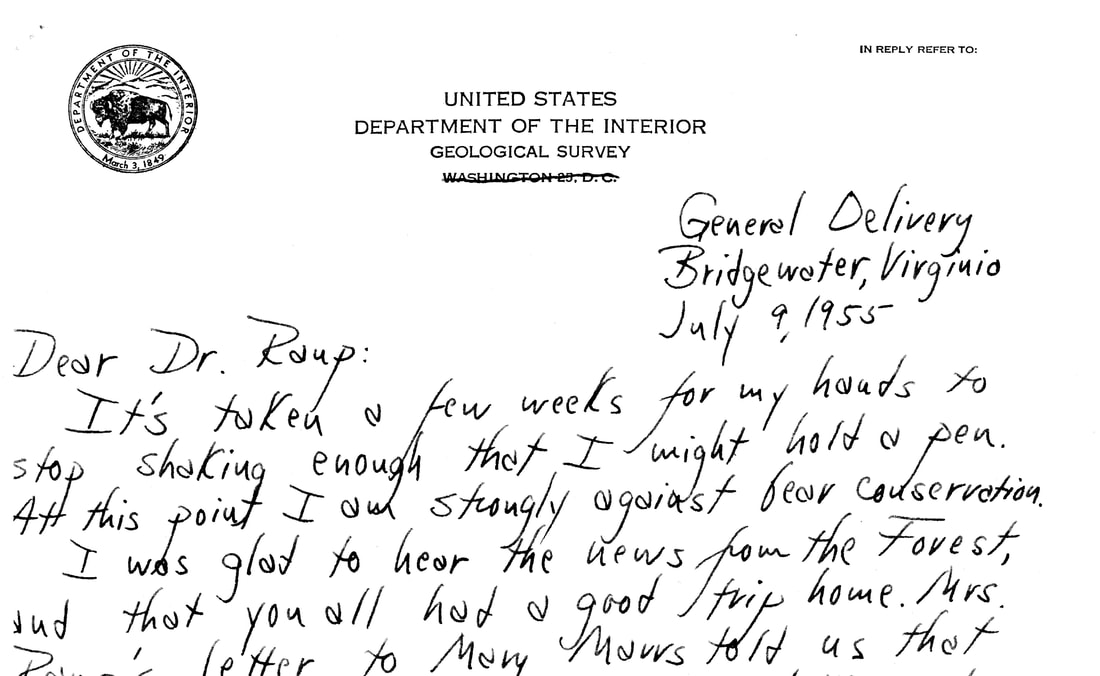

Pud Goodlett and Charlie Denny fire up the grill in Plattsburgh, N.Y., in 1966. Photo provided by Harvard Forest. Pud Goodlett and Charlie Denny fire up the grill in Plattsburgh, N.Y., in 1966. Photo provided by Harvard Forest. I I'm thinking it’s time to close the chapter on reminiscences about my dad. Compiling The Last Resort provided a tiny window into his thoughts as he hung out with Bobby and the others at their Salt River camp. By poring over the journal that he kept while working at Harvard Forest, I learned that he struggled with the same sorts of issues we all do as we launch a career. I discovered his sense of humor and his wry take on the world. The project allowed me to presumptuously call strangers and initiate conversations about their own memories of Pud. Amazingly, it prompted others to reach out to me and share their stories. What a journey it has been. I’m not saying I won’t write about him again, but I worry that this little habit of mine has become outrageously self-indulgent. I recall the first time a reader of The Last Resort approached me and said, “I loved your book. But you know it’s really about a little girl searching for her father.” I was so embarrassed. That was not at all what I had intended. But that was, of course, exactly what I had delivered. Occasionally, however, a chance comment from a family member or a former colleague of my father’s reveals another truth. Pud’s premature death at age 44 shattered lives. Of course, we can start with my mother’s. I only knew her as a somewhat withdrawn, perhaps depressed, but deeply intelligent woman who evidently struggled to find her equilibrium after my father’s death. Others, however, tell stories of her being the life of the party. Photos of her as a young adult reveal a gaiety I rarely saw. Like many widows and widowers, she never fully recovered. The family of my father’s sister, twelve years his senior and his legal guardian for a time after his own father’s death when he was 10, tell me how she grieved his death almost like she had lost her own child. My father’s older brother, with whom he was very close, rallied to my family’s aid immediately after my father’s death. Then my uncle went into a dark spiral, taking his large family on a heart-wrenching journey before his own death six short years later. Not having any sons of his own, my dad was particularly fond of his nephews. We have evidence of that. Pud writes letters to Davy after being drafted into the Army. He takes numerous photos of Davy and Sandy as toddlers. He takes Mac and Charley under his wing. He beams with pride as Bob’s music career takes off. He invites any who will join him to Camp Last Resort. Just recently, at Harvard Forest, we were shown a handsome “Memorial Album” of photos that his Harvard Forest colleagues compiled after his unexpected death in 1967. He was respected as a scientist and cherished as a friend. Before stopping by Harvard Forest, I attended the memorial service for Ann Denny, the wife of one of my father’s good friends and regular collaborators, Charlie Denny. The Dennys’ three daughters were particularly fond of both my parents, having spent a summer with them in Coudersport, Penn., as the botanist and the geologist conducted their first collaborative research. Their stories of my father’s role in their lives and in their parents’ lives are precious to me. In 2006, I visited Reds Wolman, the man who had finally snagged my father from Harvard Forest and lured him to Johns Hopkins, where Reds would become a legendary professor. Nearly 40 years after my father’s death, Reds’ face was stricken when he declared that my father’s untimely demise had robbed him of his best friend. I am, of course, leaving out dozens of others whose lives were affected by my father’s death. His graduate students, who were depending on him to guide them to a doctorate. His childhood friends like George McWilliams, Lin Morgan Mountjoy, and Bobby Cole. His extensive clan of cousins. Our neighbors in Baltimore. If you’re like I am, you don’t expect to leave much of a ripple behind. You don’t think you’ve done anything extraordinary. But take just a moment to consider the repercussions of this one life that began in a small town in rural Kentucky. Although it was a life cut short, take heed of the ripples emanating from that weighted hook cast endlessly into the slow-moving river. In loving memory of Dr. William S. Bryant (November 9, 1943 - August 5, 2019). The Last Resort never would have been published without Bill Bryant. Shortly after his article about John C. Goodlett appeared in the Kentucky Journal of the Academy of Science in 2006, Billy—as I had always heard him called—got word to me that he would be talking about the paper at a meeting of the Anderson County Historical Society. Since I was working in Lexington at the time, I contacted Bobby Cole, my dad’s good friend and fellow architect of Camp Last Resort, and offered to take him to the meeting. When we arrived, I saw that at least one more of my dad’s Lawrenceburg High School classmates was there: W. J. Smith. It was a remarkable evening of two generations sharing stories and reminiscences. I was astonished that, more than 40 years after his death, my dad’s contributions to the scientific community had prompted both Bill’s article and this hometown gathering. They’re all gone now—Bobby, W. J., George Jr., Lin Morgan, Rinky, John Allen, Jody—and now Bill Bryant is gone, too. Before the article was published, I had had no idea that Bill was working on it, no idea that he had been talking to my dad’s old colleagues (Reds Wolman, Alan Strahler, and Sherry Olson, for example). I now understand that Bill had discovered the very correspondence between my father and his Harvard Forest mentor, Hugh Raup, that I reviewed in detail just last month. In short, I had no idea that there was still any interest in my father or his work. But what I learned was that Bill knew more about my father than I did.  American Bellflower near the remains of the chimney at my dad's camp on Salt River. American Bellflower near the remains of the chimney at my dad's camp on Salt River. Twice he led me out to my dad’s old camp on Salt River. I had never been there before. It had evidently never occurred to anyone else in those 40 years that I might like to see the place that was so special—almost sacred—to my father. A few years later, as I worked on the book, Bill patiently reviewed various sections for accuracy. He encouraged me. He believed what I was doing had value. He also nudged me to include more about my mother in the book. I remember Bill visiting our home in the 1970s, talking with my mother, going over materials related to my dad’s work. I didn’t fully understand then what his interest was. But he was obviously taken with my mother’s intelligence, her courage, and her struggles to raise two daughters alone. In the end, though, I couldn’t figure out how to incorporate more of her story into The Last Resort. I promised Bill I had another project dedicated to her. It pains me that he’ll never get to read the novel I wrote about her father. Bill loved reading fiction and he loved history. I think he would have been interested in my telling of this Kentucky tale. I feel, in a way, that I’ve lost another family member—yet one more of the few remaining connections to my father. Just as I wrote recently that I wish I could have walked the woods with Pud and gleaned a thing or two from all that he knew about its inhabitants, so I wish I could have walked the woods one more time with Bill.  Pud Goodlett in 1957. From the Harvard Forest archives. His wry humor was legendary among his friends and colleagues. Pud Goodlett in 1957. From the Harvard Forest archives. His wry humor was legendary among his friends and colleagues. Tim Cooper, of Oakdale, Minn., reminds us of the human truths we can uncover from personal letters. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. A couple of years into my pursuit of an undergraduate degree at the University of Minnesota, I was threatened with summary expulsion. No, it wasn’t my grades; I had finagled my way into the honors program and maintained high marks. And no, it wasn’t my youthful predilection to juvenile delinquency—I was too busy studying to sustain that lifestyle. Rather, as the registrar’s office curtly informed me, I had failed to declare a major prior to the onset of my junior year. Two days before the deadline, I met with a professor who would become a mentor and friend until the end of his life. Professor Paul L. Murphy—constitutional historian; social-justice advocate; Pulitzer Prize finalist; and gentleman—took an early interest in me. Professor Murphy and his wife would often invite me to dinner at their home where I was accepted as a “sibling” to his two daughters. What he saw in me, I don’t know. But his guidance in any number of issues always gave me clarity. What did he say? “Timothy,” he intoned, “what academic major other than history will allow you to read, analyze, and discuss other people’s letters and diaries?” It wasn’t advice, it was an observation. And I was sold. The next afternoon, 30 minutes before being asked to pack my bags, I entered “history” as my major. I haven’t looked back. Nor did I think much about this incident until the passing of my grandmother some years later. When my father and I cleaned out her home after her death, we found stacks of notebooks comprising my grandmother’s diary, which she had maintained from the age of 8. Her entries were initially written in Gaelic, the tongue of her native Ireland, and then suddenly transformed into proper English after she settled in the U.S. as a young immigrant. Finally, barely 10 days before cancer’s ultimate victory, she just as suddenly returned to her native language. Indeed, this recapitulation to Gaelic happened mid-sentence. Her final entries were all in Gaelic. When I read those diaries, I recalled Professor Murphy’s observation. Recently, I again remembered my mentor’s words when Sallie Showalter forwarded to me a file of her father’s correspondence from the Harvard Forest’s archival collections. I cannot describe the excitement I had scanning through Pud’s letters. Let me try to explain. In them we see the arc of his relationships with family and friends, as well as his professional interactions and scientific observations. But more importantly we see the development of a “voice,” of an academic rueful and wry one minute, proper and scholarly the next. I read them and felt as if this absent and unknown man, a man I have known of since I was 15 years old but never met, was speaking to me. And I like him, enormously. I understand his world-vision, his striving, and his occasional self-doubt. But it is his humor—and his horrible handwriting—that sing to me. Letters and diaries do that to you. So let me end in a plea. In the next few days, I ask you to recover paper and pencil or pen, envelope, and stamp. Think of a loved one, a family member, a friend, or an acquaintance. Write that person a heart-felt letter in your own hand and post it by “snail-mail.” The subject doesn’t matter. It can be humorous or serious, gossipy or informative, apologetic or explanatory. An unexpected letter may mean more to the recipient than you can anticipate. And you never know what historian will relish your words in some unimagined future. Ed.--On June 23, 1955, Pud and his colleague John T. Hack were chased off a mountain near Bridgewater, Va., while doing work for the U.S. Geological Survey. They encountered eight other bears while conducting their research, but only one—a mother with two cubs—"attacked." The incident was enshrined in a local newspaper, in family lore, and--as in the following examples--in Pud's own self-deprecating humor. In the following excerpt from a letter dated June 20, 1956, Pud tries to reassure Dr. Hugh Raup, the director of Harvard Forest who was out of the country for the summer, that all is well at the Forest during his absence.

|

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed