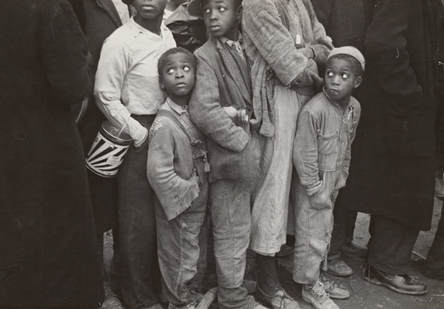

"Flood refugees at mealtime, Forrest City, Arkansas," 1937. Photo by Walker Evans. From The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "Flood refugees at mealtime, Forrest City, Arkansas," 1937. Photo by Walker Evans. From The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. Empathy, like civility, seems to be a vanishing American quality. The ability to imagine oneself in another person’s situation and understand that person’s feelings typically engenders compassion and a sense of shared human experience. Without empathy, we tend to align ourselves with others whose experiences we can identify with. That results in homogenized communities and a bubbling fear of those who are different—the threat of “The Other,” as described so vividly in Ryszard Kapuściński’s book that borrows that title. That’s where our nation—and much of the world—finds itself right now. Bill Bishop, formerly a columnist with the Lexington Herald-Leader, relied on demographic data to sound the alarm about this phenomenon in his 2009 book The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart. He argued that our choosing to live in neighborhoods with others who share our lifestyle and our beliefs has helped create the political and cultural polarization we see today. Unfortunately we currently have political leaders who find stoking those fears useful for holding on to their power. By promulgating misleading data and straight-up lies, they are able to prey on people’s fears of those who are different—or simply unfamiliar—and push agendas that lack compassion and humanity. Our nation has a long history of persecuting immigrants and those whom we perceive to be different. We have been callous, hateful, distrustful, even cruel—all while pointing smugly to the Statue of Liberty, our national symbol of compassion. It is our responsibility as citizens to distinguish the facts from the untruths and to consider the effect of proposed policy on all people, not just those who look and think like we do. So how do we build empathy for others who live very different lives from our own? If you live or work among a diverse population of people, it’s much easier. You interact with people with different backgrounds from yours every day. So talk to them. Get to know them. Ask them questions. Share a meal. I expect you’ll find you’re not very different after all. If you live and work in an area with little diversity, as I do, you have to work a little harder to discover the empathy and compassion necessary for a united nation truly interested in justice for all. You can volunteer to work with groups of people whose life experiences are different from yours. If you have the means, you can travel. You can take classes or attend public lectures. But perhaps one of the simplest ways to develop empathy is to read. Read widely. Read everything you can get your hands on. Read books by authors from other countries. Read history so you’ll know the struggles of those who preceded us. Read biographies about people you’ve never heard of. And read fiction. Good fiction invites you into a world you know nothing about and engages your emotions in a way that encourages you to feel empathy for the characters. Whatever their situation—however different from anything you’ve ever known—you begin to identify with the fictional characters: you feel their pain, their sorrow, their happiness, their embarrassment, their fear. You struggle with their decisions. You want them to succeed. You live their lives vicariously. If reading fiction is not a regular part of your life, here are a few suggestions to get you started. Of course, there are hundreds of others to choose from. Feel free to share a comment below listing other books readers might find compelling.

In the second Appendix of The Last Resort, Pud lists what he is reading while working as a researcher at Harvard Forest. The almost wacky list includes a historical thriller, a collection of essays by the humorist James Thurber, a contemporary novel, a telling of Maurice Herzog’s trek up Annapurna, and a book of Ozark folk tales. He was also rereading Thoreau’s Walden and working his way through Ridpath’s history. In 1953, Pud and Mary Marrs had no television. Reading was their primary pastime. I suspect that in that era more people read more widely. With the widespread establishment of public libraries and the advent of paperbacks, books became more accessible. Newspapers were commonly found in homes. Magazines were popular. But in the digital age, we read “soundbites.” We rarely dig deeply into a story or analysis. Fewer still pick up a book or download a novel to an electronic device. Who has time for that? As we once again consider important policy and legislation relating to immigrants, refugees, foreign aid, and how we respond to national disasters that disproportionately affect the poor and marginalized, let us all summon as much empathy and compassion for our fellow travelers as we possibly can. Let’s all pick up a good book and read. And then let’s make our voices heard. For another call to action, please read the comment left by Vince Fallis at the bottom of Tragic Patterns.

0 Comments

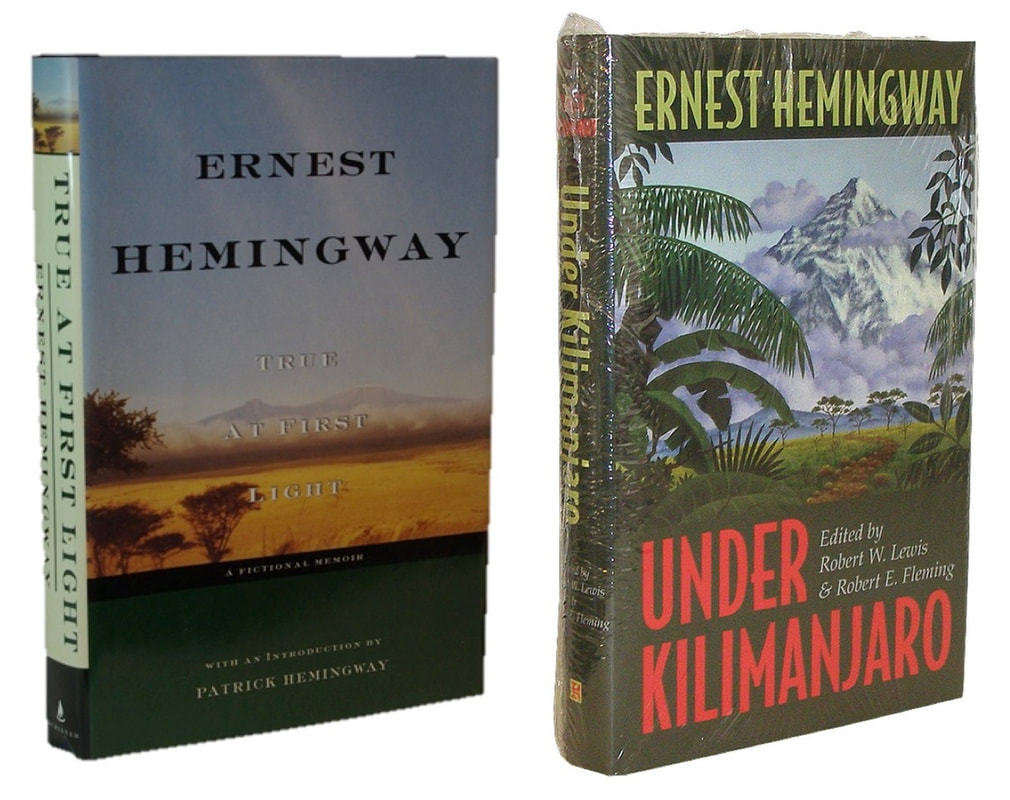

Mary and Ernest Hemingway in Kenya during his second African safari (1953). Mary and Ernest Hemingway in Kenya during his second African safari (1953). David Hoefer, of Louisville, Ky., is co-editor of The Last Resort and the author of the book's Introduction. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. It will surprise few readers to learn that editing a previously unpublished manuscript is not unlike wading waist-deep into an endless stream of choices. At least that’s what Sallie and I found in preparing Pud Goodlett’s 1940s Salt River journal for publication as The Last Resort. We felt a moral obligation to reproduce the author’s original text as faithfully as possible, but other considerations managed to creep in. Some of them were practical—for example, pencil smudges and strikethroughs in the source document required interpretive skill. There were also, on occasion, plausible arguments for more extensive revision. Does one correct spelling errors? Pick grammatical nits? What about gray areas like replacing period slang or clunky phrasing with something easier to read (after all, Pud was only 19 when he started his journal)? Aren’t editors supposed to edit? Sallie and I erred on the side of laissez faire et laissez passer—let do and let pass—but not everyone follows the same strategy. An interesting counterexample involves an unpublished manuscript by the patron saint of outdoor writers, Ernest Hemingway. Though he’s often associated with big-game hunting in Africa, Hemingway undertook only two safaris during his lifetime. The first occurred in 1933 and resulted in Green Hills of Africa, published two years later and viewed by some as the gold standard for this genre of writing. The second took place in the early 1950s and generated an unfinished 850-page manuscript, partly handwritten and partly typed, deposited by Hemingway for safekeeping in a Cuban bank vault. Since Hemingway’s death in 1961, “the African book” (as he called it) has been published not once but twice in two very different versions. The first, appearing in 1999 and given the name True at First Light, was heavily edited by Hemingway’s son, Patrick. It was, after a fashion, a father-and-son collaboration. The same manuscript served as the source for a second publication, Under Kilimanjaro, in 2005, edited by a pair of Hemingway scholars, Robert W. Lewis and Robert E. Fleming. They took the opposite approach, leaving the original manuscript largely intact. According to Lewis and Fleming, “[T]his book deserves as complete and faithful a publication as possible without editorial distortion, speculation, or textually unsupported attempts at improvement.” Sallie’s and my approach was more Kilimanjaro than First Light, which isn’t to say that we didn’t earn our paycheck as editors (speaking figuratively here, as there’s no money in scholarly self-publication). The appendices of World War II correspondence and the Harvard Forest journal were created after a meticulous review of the source documents and an appropriate reduction in size and scope. The introduction, annotations, taxonomic list, and other content additions involved considerable time and required input from both of us. But the point of the book—Pud’s delightful journal of halcyon days on Salt River—is as verbatim as we could make it. The Last Resort is the authentic work of an authentic voice before our current period of largesse and decline.  John C. "Pud" Goodlett, May 1, 1922 - April 1, 1967. [Photo courtesy of Bob Cole] John C. "Pud" Goodlett, May 1, 1922 - April 1, 1967. [Photo courtesy of Bob Cole] Last spring I silently marked the 50th anniversary of my father’s death, on April 1, 1967. It seemed fitting that shortly after that anniversary David Hoefer and I committed to publishing The Last Resort by the end of that summer. This spring the entire nation has marked the 50th anniversary of the deaths of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy. As an eight-year-old in the spring of 1968, my world seemed to be wracked by death. My father the year before. His mother two months later. Then two towering icons whose deaths recalled the raw wound left behind after the murder of John F. Kennedy five years before. Of course, the whole nation had other reasons to grieve that year, as more and more servicemen had their lives cut short in Vietnam. Drug overdoses made the news. Death and despair seemed to have a determined grip on our nation. In many ways I realize it’s unfair to conflate my personal losses and the nation’s loss of these public figures. But from the limited perspective of a child, the incessant drumbeat seemed overwhelming. I couldn’t understand why all of these important people were being taken from us—from me—one right after the other. One in April 1967. One in April 1968. One in June 1967. One in June 1968. Even at that young age I had a sense of the symmetry—or perhaps the regularity—of these deaths. I had no reason to think the next year, or the next, would be any different. These men were all linked, at least in my young mind. All were in the prime of their lives—from 39 to 46 years old—having steadily built their influence. All had families with young children. All died unexpectedly, the family members and admirers having no preparation for the sudden emptiness, the sudden annihilation of a shared future. All represented huge promise—for a nation in turmoil in the case of the assassinated public figures, or for a tiny sphere of students and colleagues in an emerging field of science, in the case of my father. In retrospect, it doesn’t seem so outlandish that a young child who had been immersed in grief would take these continuing deaths personally. This was the world as I knew it. Sadness. Loneliness. Endless inexplicable tragedies. I knew the commemorations surrounding the anniversaries of the 1968 deaths of two of our most inspiring public figures would affect me. I expected it would be best if I buried my head and blithely went about my business this spring without recognizing them. But the condition of our nation and our politics at this moment made it impossible for me to keep my head bowed. I feel it is my responsibility to raise my head up, to stay vigilant, to maintain a clear-eyed gaze. I’m certain it’s good for our nation as a whole to honor Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy. I would hope that by remembering the unfulfilled promise of their lives and the hopefulness of their messages we would be inspired to alter how we think, how we act, and how we treat each other, even on the smallest scale. But I’m afraid I may be one of the few who is paying attention.  Our newest Mallard ducklings, who arrived this week. (All photos by Rick Showalter) Our newest Mallard ducklings, who arrived this week. (All photos by Rick Showalter) Well, it’s official. Here in central Kentucky, we actually did go straight from winter into summer. You may recall that March and April were colder than normal, with several days of measurable snow, according to National Weather Service meteorologist Ron Steve. Here on the lake, we enjoyed an extended ice skating season, something that has only happened two, maybe three times in the 20 years we have lived here. Then, suddenly, May felt like summer. According to Steve, “Not only was it the hottest May ever—more than a full degree warmer than 1962's average of 71.6 degrees—it was also warmer than the average June temperature of 72.5 degrees.” And just for fun, let’s also celebrate that we enjoyed “one of the wettest [Mays] on record, with 7.45 inches of rain,” according to WKYT chief meteorologist Chris Bailey. Somehow, though, despite this unusual fluctuation in our weather, nature eventually fell into its typical rhythms, even if a little off-beat to begin with. One week in late April I finally noticed dogwoods blooming along the lake shoreline, a field of buttercups beside the road, flowers in the horsechestnut trees, Baltimore Orioles sweeping through my yard, and Red-winged Blackbirds and Tree Swallows patrolling near the water. A week or two later, fragrant black locusts abounded and yellow lilies brightened the edge of the lake. Our resident bat, Bruce, who normally arrives in late April for a summer of insect gorging around our back patio, didn’t show up until May 10. We were beginning to worry about him—and about mosquito season if he didn’t return—so there was a family celebration when he was eventually spotted In his usual corner of the rafters outside my office window. There seem to be fewer pairs of Canada Geese with goslings this year, but I have no idea whether that’s related to our non-existent spring. Three tiny Mallard ducklings appeared just this week, so we still have babies making their debuts as we get into June. And, of course, in our neighborhood, we always look forward to a new season of fawns. This year, a larger number of turtle hatchlings have been visible away from the water. This tiny fella thought our patio looked like a warm spot to sun. I can lament the effects of climate change, count up the human costs in lives and dollars, bemoan the potential loss of species and habitats, and rage about our reluctance to pay attention to the signs, but this season I’ll simply take heart that nature adjusted her schedule to accommodate the perverse weather patterns. Lush summer has arrived and, thankfully, the babies appear to be thriving. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed