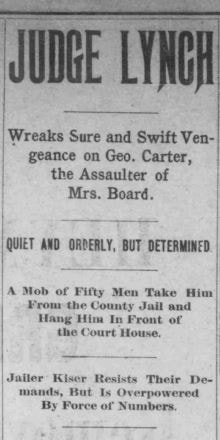

A headline from The Bourbon News, February 12, 1901 A headline from The Bourbon News, February 12, 1901 This week our dark times got darker. Over the month of May—still sheltered in place or cautiously emerging into society while simultaneously mourning the 100,000 Americans who have died from COVID-19—we have learned of three American citizens killed, needlessly, inexplicably, by police or those assuming law enforcement duties. All the victims were black. All the perpetrators were white. Will this outrage never end? The rage incited by these events has engulfed our cities. Protestors have blanketed the streets. Some agitators have destroyed property, burning and looting businesses with no association to the injustice. A response that initially felt rational now feels insane. In the midst of all this horror, another related story caught my attention. On Monday in Central Park, a 57-year-old birder asked a woman walking in the wooded Ramble area to leash her dog, as the area requires. She refused. As he calmly offers the dog treats in an effort to convince her to control her dog, she accuses him of threatening her and says she will call the police. With that, he takes out his phone and begins to record the incident. The woman, who is white, then calls 911 and tells the dispatcher, in an increasingly hysterical voice, that she is being threatened by an African American man. (CNN story) We all know of famous incidents in our nation’s history where a false accusation from a white woman cost a black man his life. But how many others, never reported or denied by those in power, stain our past? Today we’re finding that an immediately accessible recording device may be the only way for the black victim to get justice, even if it’s posthumously. In the Central Park instance, which thankfully did not go that far, the man and the woman actually have a lot in common. They’re both sophisticated New York City dwellers who take advantage of the beauty of Central Park. They’re both highly educated—he at Harvard, she at the University of Chicago. They’re both successful in their fields. They even share the same last name (although they are not related). But Amy Cooper felt that her whiteness gave her tremendous power over Christian Cooper. And she decided to use that power. If he had not recorded their interaction, she very well may have succeeded in having him arrested for a fabricated crime. And convicted. Because of his skin color. As I worked on Next Train Out, I had to wrestle with my own family’s story of a white woman’s alleged assault leading to a black man’s death. The only information I have about the incident is what was reported in the local and national newspapers, during a time when purple prose and editorializing were evidently acceptable. None of the news articles offers any details that might indicate that what happened should have been a capital crime. The only witness was an eight-year-old boy, my grandfather. In my fictional telling of the story, I chose to assign him the natural empathy and compassion of a human innocent, someone not yet indoctrinated into the mores of his community’s power brokers. Over our long and tortured history, I suppose we humans have always sought to subjugate others. To demonstrate power through domination. To cover up weakness by claiming the upper hand. At risk of repeating a tired refrain, this has to end. We must stop snuffing out the lives of others simply because we deem ourselves superior. The color of our skin does not grant us that privilege. We have to be better.

2 Comments

I have never considered myself creative. I’m a dogged rule-follower. I can read music but couldn’t improvise if you put a gun to my head. I can follow a recipe but rarely experiment in the kitchen. I could never dream up a clever Halloween costume, and I eventually came to hate a holiday that I had loved as a child because of it.

I have absolutely no artistic ability: I can’t draw or paint or sculpt. I have no interest in or talent for what some might call crafts, including scrapbooking or photo collages or needlework of any type. In fact, in high school I tested in the bottom tenth percentile in spatial aptitude. So much for a career as an architect. But recently my cousin Charley shared an article that made me rethink my capacity for being creative. In fact, it made me realize that it may well have been my bent toward creative thinking that hounded me throughout my sketchy professional career. For me, every problem was simply a puzzle to be solved. What I didn’t understand was that solutions that seemed obvious to me were perhaps unimaginable to others. Was it my fearlessness, my ability to envision a positive outcome, my willingness to tackle something new in unexpected ways that frequently made my co-workers so ill-at-ease? In the article “Secrets of the Creative Brain” (The Atlantic, July/August 2014), Nancy C. Andreasen shares the results of decades of research into some of the great creative geniuses of our times, both in the arts and the sciences. Some of these individuals’ common characteristics may not be surprising, but they hit home for me. For example, she found her subjects were “adventuresome and exploratory,” and they were willing to take risks. Check. She added that “Creative people tend to be very persistent, even when confronted with skepticism or rejection.” Check again. Once I’ve decided something is possible and laid out a plan for getting there, I don’t back down. I’m heading to the finish line, whether you’re coming with me or not. Andreasen also relays that many creative people have broad interests across many disciplines, and they are good at making unexpected connections. That, for me, is the essence of good writing—connecting disparate things in surprising ways, using language or metaphor to awaken the reader’s senses. I’ve always been interested in lots of subjects, but I know little about any of them. In a typical day I bop from immersing myself in politics to paddling on the lake and admiring the wildlife to researching a technical computer issue to reading a novel about World War II to trying to understand a poem that a friend has shared with me to romping with the dogs in my neighborhood. I hate routine. I love variety. I never want to do the same thing twice. In graduate school, my department chair railed against "dilettantes," declaring he would have none in his classes. I would laugh and wonder, “What else are we?” I recall sitting in fiction writing classes recently and wondering how on earth writers come up with the story lines and the scenes and the conflicts and the dialogue necessary to create a compelling narrative. Up to that point, everything I had ever written had been based on facts, whether I was preparing a technical manual or promoting an art event or writing a faculty member’s bio. I’ve come to realize that what I sorely lack is imagination. Not creativity. Many have asked me about the subject of my next novel. I swear that I’m a “one-and-doner.” Starting with the realities of a person’s life let me cheat the first time. How could I possibly invent a story and a plot and the characters whole-cloth? I simply don’t have the capacity to do that. But perhaps I will begin to think of myself as creative. I recognize that I tend to look at things a little differently than others. I am fearless. I don’t mind choosing the untrodden path. I embrace making choices that might bewilder others. I might even propose outlandish courses of action. Sometimes they work. Sometimes they don’t. But nothing will hold me back if I think I have a shot at accomplishing it.  A brilliant redbud, before May’s freezing temps. A brilliant redbud, before May’s freezing temps. What a strange spring. What a strange year. During the winter months, I’m not sure we had five nights when the temperature dipped below freezing. Here, in the middle of May, we’re trying to make up for it. I noticed this morning that the leaves in the tops of my redbud trees and tulip poplars are black and crumpled. I’m reading that this will not damage the trees, but after one of the most beautiful redbud blooming seasons that I can remember, it’s hard to see the trees’ new leaves suffer in the cold. It’s May 10, and we have yet to see any goslings or ducklings on the lake. This seems unusually late, but I remain hopeful as I continue to see Mallard and Canada Geese pairs waddling around the neighborhood. And there is a large bird, perhaps a Blue Jay, sitting in a nest just beyond my office window, so some natural spring activity is taking place. Recently I’ve noticed a lot of birds I don’t usually see: a Red-headed Woodpecker, an Eastern Kingbird, a Scarlet Tanager pair, a Yellow-rumped or Myrtle Warbler with its three astonishing yellow patches. We also seem to have plentiful Tree Swallows, Barn Swallows, Red-winged Blackbirds, Bluebirds, and Killdeer, despite the acres and acres of woodlands that have been turned into muddy deserts here in our neighborhood. Do I have more time to look for them this year, or are they moving into territories where they haven’t always been as plentiful? The whole world seems upside down to us right now, of course. Nothing seems normal. I guess it’s no surprise that even Mother Nature seems a little off. Perhaps as I acknowledge the usual harbingers of spring, the sheer ordinariness of those events will nudge us toward a more unremarkable time. Occasionally I have wondered aloud whether the novel coronavirus isn’t Mother Nature’s way of resetting the balance. Few can seriously argue that we haven’t wreaked havoc on this world that nurtures us. Our sheer numbers strain the earth’s resources. And the planet doesn’t need humans to sustain its ecosystems. Without our presence, other predators would pick up our load, or illnesses like chronic wasting disease would run through animal populations, thinning the herd. Much like COVID-19 appears set on thinning ours. As this pandemic has forced us to put many human activities on pause, nature has been busy reversing the deleterious effects of our obsession with productivity. Around the world, water is cleaner, air is purer, animals such as sea turtles have nested without human interference. In just a few short months, nature has begun to reclaim its domain. Sitting comfortably in my home, I can’t ignore that this is occurring amid massive human suffering from an unstoppable virus that has stolen hundreds of thousands of lives and destroyed economies. The long-range effects of this pandemic, both human and otherwise, cannot yet be imagined. If the human race is to survive, we must, and we will, apply our scientific knowledge toward finding a way to exist with this virus in our midst. But while we’re focused on that critical task, can we not also recognize the value of adjusting our impact on this earth so we eventually live as grateful recipients of its abundance, rather than as relentless destroyers of the gifts it has to offer? |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed