Chicory blooming on September 24, 2017. (Photos by Rick Showalter) Chicory blooming on September 24, 2017. (Photos by Rick Showalter) As they say in Kentucky (and I imagine a lot of other places): If you don’t like the weather, wait a minute and it will change. Last Sunday I remarked how the fall colors were beginning to overtake the trees along the shoreline of the small lake where I live. That was nearly a month earlier than usual. This morning as I walked my dog, I was startled to see bright blue blasts of chicory all along the roadside. I look forward to the chicory every summer. It adds an appealing dash of color to my walks around the neighborhood. In small stretches where the sturdy purplish-blue wildflowers have managed to dodge the mowers, they explode in a profusion of color, as if they have been cultivated by a particularly determined gardener. Sometimes they’re gone the next time I walk by, felled by a weed whacker wielded by a callous homeowner. But all of that drama usually occurs in early to mid-summer. Our weather this fall has been so peculiar that even the chicory is confused…or perhaps emboldened. It’s as if this hardy member of the dandelion family (Asteraceae) just decided that a series of early fall days in the high 80s was the perfect time to show off the sun salutation poses they had been practicing in their seeming dormancy. Of course, we in Kentucky have had little repercussion from the record-setting weather that has plagued many across the U.S., including those experiencing the traumatic effects of hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and now Maria. We feel almost contrite in our lack of misery: we’re not dodging wildfires or monitoring rising floodwaters. Our weather may have been peculiar, but it hasn’t been catastrophic. But even these smaller peculiarities may be harbingers of permanent changes we need to accept: vegetation extending its natural habitat north as warmer average temperatures become the norm; fiercer storms wreaking havoc in our communities; flooding occurring in areas that have never experienced it before. If we care about this earth, with all its beauty and its ferocity, we need to pay close attention to what these changes are telling us. We can stop and admire an unexpected display of color, but we also need to be prepared for the sometimes tragic consequences of this new order. It’s up to us to make responsible decisions about how we choose to live amid this wonderful and sometimes chaotic natural world that sustains us.

1 Comment

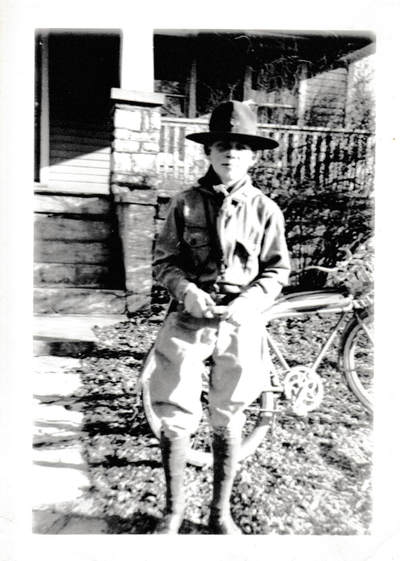

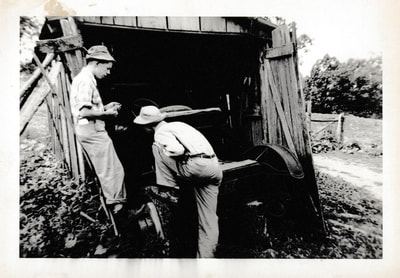

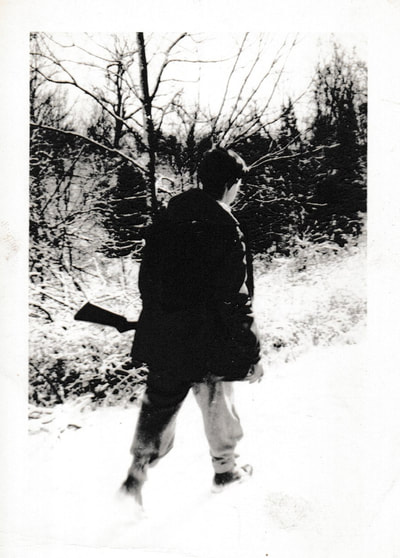

A fall beauty along Mallard Point lake in October 2015. Photo by Rick Showalter. A fall beauty along Mallard Point lake in October 2015. Photo by Rick Showalter. I live on a small lake, and Sunday, amid an unexpected resurgence of summer, I took my lightweight kayak for a paddle around the lake’s perimeter. I was surprised to see how many trees along the shoreline were already displaying their fall colors. The sugar maples glowed with yellow and orange and dots of red, their robust hues shimmering in the water’s reflection. Black oaks were draped in burgundy. One black gum had completely surrendered to its autumn red and was already dropping its leaves. We’re having what feels like an odd transition from summer to fall. The lake swimming season ended unusually early, as we experienced a cool, rainy couple of weeks. And now fall appears eager to take the stage away from the sumptuous summer green. As is frequently the case when I paddle on the lake, I saw two Great Blue Herons take flight and several Green Herons along the water’s edge. I’m fairly certain it was a Double-crested Cormorant that abandoned its spot among a large group of Canada Geese as I paddled by. All sizes of turtles were enjoying the sun’s rays on downed logs, and I nearly paddled over what appeared to be a family of two larger turtles and two smaller turtles swimming in a line right at the water’s surface. I returned home to find my yard covered with deer grazing on the new grass that emerged after recent rains. I have always reveled in the natural world around me, but working on The Last Resort has made me pay even keener attention. I learned a lot from Pud and the notations he made in his journal. There are still trees and birds that I can’t identify, as well as a frustratingly large number of wildflowers. But I realize how fortunate I am to live in an area where I can be in a stand of woods or on the water in minutes. I can take refuge in nature in the blink of a doe’s eye. As we live among hurricanes and political tsunamis, it’s sometimes difficult to find simple ways to manage the erosion of peace and tranquility and civility in our world. I have one reliable way to cope. Like Pud, I just head outside.  The essence of Pud (John C. Goodlett): in his Boy Scout uniform with his bicycle in front of his home outside Lawrenceburg, around 1934. The essence of Pud (John C. Goodlett): in his Boy Scout uniform with his bicycle in front of his home outside Lawrenceburg, around 1934. The other day I was rummaging in a cabinet looking for a manila envelope. I pulled one out that appeared to be the perfect size for what I needed. I was disappointed, however, to discover that it already had something in it. My name was scribbled on the front, but I had no idea what it was. When I opened the clasp and dumped the contents, I gasped. Dozens of black-and-white family photos from the early 20th century tumbled out. There were photos of my mother and her family from the 1920s and later. Photos of my Goodlett cousins when they were young. And photos of the second wave of boys who visited The Last Resort in 1943, when Pud was looking for others to hang out with him after Bobby Cole, Rinky Routt, and the older boys had gone off to fulfill their military duties. I was flabbergasted. And dismayed. I still can’t believe that I was not aware I had these treasures in my possession. My guess, from the notes on the back of some of the photos, is that my cousin Bob McWilliams had given me this packet at a family gathering some years ago and I had put it away without understanding the significance or the value of the contents. It had to have been before I seriously started working on The Last Resort, or the names of the young boys would have had more meaning. As I started the project, I spent a lot of time trying to identify the Boy Scouts who joined Pud at the camp late in the journal. They weren’t household names for me. I tried running the list of names by my older cousins. I searched the archives of Lawrenceburg High School class rosters at the Anderson County Board of Education. I attended a wonderful reunion of all LHS classes, hosted by Eugene Waterfill '39 and Ambrose Givens '42 who, sadly, are both now deceased. What a memorable day that was, talking with people who could share stories about my mother, Mary Marrs '39, and my father, Pud '40. After all of that, I finally had some confidence that I had accurately identified the boys. Three of them are pictured here: Bobby Paasch '44; Reuben “Junior” Jamerson '48; and Don Towles '45, who went on to become an executive at the Louisville Courier-Journal. I’m heartbroken that I didn’t realize I had these pictures before I published the book, because they certainly warranted inclusion. But at least I can share them with you now. They have already made my interpretation of Pud’s journal richer, and I hope they make you want to take another look—or a first look—at the Journal of a Salt River Camp from 1942-43. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed