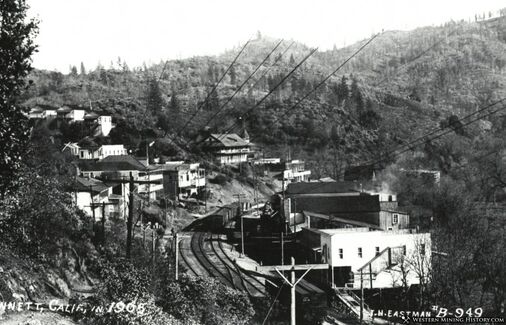

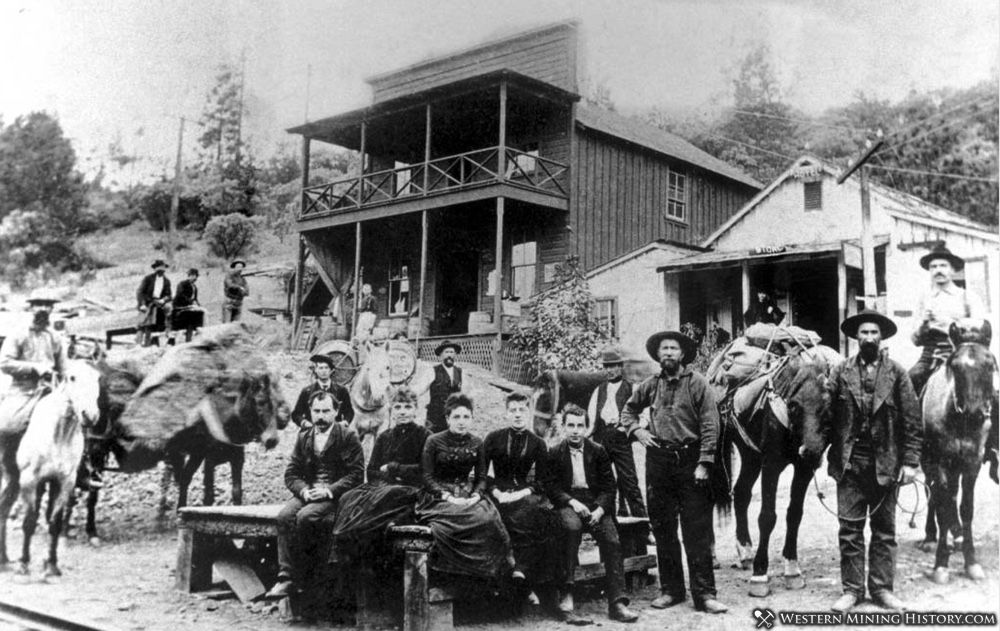

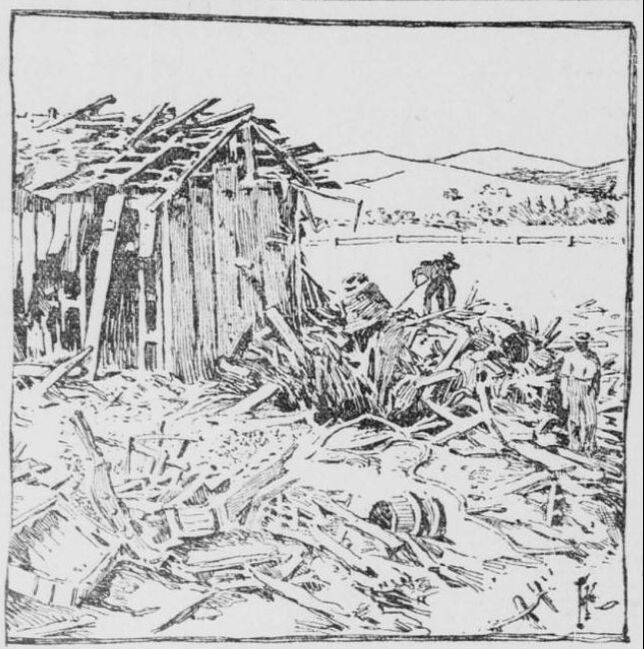

The remote community of Kennett in northern California in 1905. Some local newspapers referred to the town as “Kennet.” The remote community of Kennett in northern California in 1905. Some local newspapers referred to the town as “Kennet.” This is the third in a series of blog posts about my great-great uncle Richard T. Board, the uncle of my already infamous grandfather William Lyons Board. (Read Part I and Part II.) Many thanks again to my friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard for discovering yet another curiously dissipated ancestor of mine. It is only because of her extensive research that I am able to share these startling stories with you. As Richard Board approaches 40, perhaps he takes stock of his various schemes to find his fortune. As a young man, he evidently abandons a steady position as the deputy clerk to his father in his hometown of Harrodsburg, Ky.—or is run off for his repeated petty thefts and frauds. In 1885, when President Grover Cleveland appoints him to a federal position with the National Railway Service despite his criminal history, he steals a money order during his first trip aboard the train in New Mexico. Arriving in California sometime after serving two years in a federal prison in Illinois, he takes up with the former nurse to a soon-to-be-heiress. When no king’s ransom comes her way, he resorts to sending teenage boys into local stores to defraud proprietors. But that gets him a year in San Quentin. So what’s next? What might catch the attention of our aging antihero in California in 1899? Gold. By 1900, Richard and Mary have settled in Shasta County in northern California, near the town of Redding, with their son, approaching five years of age. The couple welcomes another baby about that time, a girl. They’re living in a cabin in the remote mining community of Kennett, where Richard is a partner in a gold mine. But it’s not long before he finds more trouble. Parties had evidently wrangled over who owned the Clipper Mine, and the courts had ruled in favor of one Alfonso di Nola over W. V. Huntington, from whom Board leased a portion of the mine. A fellow named Ross Spencer sub-leased from Board. On Monday, November 12, 1900, Spencer accompanies the newly certified owner, Alfonso di Nola, to the mine. Board appears from the mine with a gun and threatens to kill Spencer. Spencer and the three other men overpower Board and take his gun. Two days later Spencer swears out a warrant on Board for assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill, a felony. Board is arrested the next day. Simultaneously, Board is served a second warrant for a misdemeanor: passing a fraudulent $30 check at the Golden Eagle Hotel with no funds in the Bank of California to cover it. Bonds of $500 for the felony and $50 for the misdemeanor are somehow paid—or dismissed, with the help of Board’s attorneys—and Board is released from custody. On November 19 Board pleads not guilty to the misdemeanor, and the case is eventually settled out of court. On December 13 the felony charge is referred to the Superior Court. On January 4, 1901, the same Redding newspaper that has been meticulously covering the criminal charges against Board reports in the “Town and County” section that “R. T. Board, lessee of the famous Clipper mine near Kennett, spent New Year’s in this city.” Richard T. Board Jr. has once again found his way from the police blotter to the society pages. Late that same New Year’s Day, a monstrous snowstorm descends upon northern California. One hundred miles north of Redding, the town of Yreka reported 63 inches of snow had accumulated by January 3, where “snow drifts were 6-7 feet in town, and businesses came to a halt so everyone could shovel snow off the businesses and keep their roofs from collapsing.” Rather than returning home to Kennett to check on his family as the storm settles in, Board chooses to travel on to San Francisco to meet with the owners of the Clipper mine. A week later, on Monday, January 7, Mr. Robert Hart—who had been part of the group accosted by Board in November and whose life it was rumored Board had threatened even before that incident—takes another man to Kennett to check on the Board family, “thinking the heavy snow might have caused them to be in distressed circumstances.” [The Searchlight (Redding, Calif.), January 8, 1901. All subsequent citations are to this newspaper unless otherwise noted.] They discover the Board cabin has been crushed under the weight of the snow. The tableau inside is horrific. On January 17, 1901, The Feather River Bulletin (Quincy, Calif.) runs the following headline: “Five Days the Baby Lived While Starvation and Gangrene Sapped Life.” The article included this report from the Free Press: Mrs. Board was killed by a falling of the roof. She had perhaps doubted if it would hold up under the great weight of snow. She may have been in fear for hours, and had drawn on a pair of overalls as if to be ready to flee the cabin if necessary. She had gone to the buggy where her baby lay. A key carried in her hand she thrust between her teeth that she might use both hands to lift the baby. As the mother bent over, a corner of the roof gave way and the timbers fell upon her, crushing her across the baby buggy. Her throat fell across the wicker side and she was strangled to death. The lad was not hurt by the falling roof. Tracks around the cabin showed where he had crawled out and run about, probably shouting, only to be mocked by the solitude. At last weakened by starvation he had lain down by his mother's upright dead body and exposure soon brought about his death. The child in its perambulator was shielded from the cold blasts. It could not freeze, but slowly it starved. The mother's body pressed the child's abdomen and circulation in the lower half of the body had ceased. Though the child was alive after five days, when discovered Monday, its tiny feet had turned black and gangrene was reaching upward toward the knees. The little one lived only a few hours after being released. Removing the bodies is not an easy task. “It was found necessary to make an improvised sled from one of the doors of the house and upon it the bodies were drawn to Kennet over the deep snow.” (January 8)

As word spread of the tragedy, the newspapers speculate about Richard Board’s whereabouts. His horse had been found at Kennett, probably at the train station where he had embarked first to Redding and then to San Francisco. Not being able to ascertain where he was during the storm, reporters don’t hesitate to admonish him for having abandoned his family in a time of peril. He is accused of longtime negligence. Three days later he is sighted in Redding. “Thursday evening R. T. Board passed through Redding on the northbound California express en route to Kennet, from where no one knows…Early Friday morning [he] started for the Clipper mine.” (January 11) When he arrives at Kennett, he finds his family’s coffins on the platform at the station. Arrangements had been made by Mary’s sister, Mrs. Martha Beadle Gowans, to transport the bodies for burial near her home in Sonoma County. Richard has a week to come up with a story. On Saturday, January 19, he returns to Redding to make a statement to the newspaper. He tells a convoluted tale of having asked a friend to check on his family as the snowstorm arrived and he departed for San Francisco, and of three men ordering him out of Kennett when he arrived to find his family’s remains at the train station. The newspaper immediately counters its recent accusations of negligence with a rather fantastic tale based on Board’s personal report. The next day, the headline offers this new narrative: “R. T. Board Experiences a Tragedy of Woe.” The article gushes with new-found sympathy for the bereaved widower: “But few men suffer the lot of Richard T. Board of Kennet. While far from his home and loved ones on business, the result of which meant the very means of sustaining life within them, the unfortunate man was robbed of his wife and two babies by one fell stroke.” His woes are indeed piling up. On that same Saturday, Board appears before the superior court judge on the felony assault charge. When the district attorney reduces the charge to simple assault, Board changes his plea to guilty, claiming that his actions were in response to Spencer coming to his home back in November at a time when he was away and ordering his wife and children from the house while insulting his wife with “unbecoming language.” (January 25) In lieu of a $180 fine, which Board cannot pay, the judge sends him to the county jail for 90 days. Board soon discovers more anguish for his baleful lot. As the Redding Searchlight continues its rapid reformation of its opinion of Board—who’s now sitting in the county jail—it writes the following headline on February 15: “Troubles Come in Battalions: More Sorrow for R. T. Board, to Whom the Fates Have Been Unkind Indeed.” The article relays that “After having passed through troubles more than sufficient to try the stoutest heart [Board] learned by dispatches in the coast’s papers that his sister-in-law has been made the victim of a negro fiend.” The sister-in-law referenced would be my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Board, who had allegedly been assaulted on the 2nd Street bridge in Paris, Ky., in December. That incident resulted in the lynching of George Carter in front of the Bourbon County Courthouse on February 11, 1901. In response, Board writes to the editor of the Redding Searchlight from his jail cell: “My poor old mother must be heartbroken….It is almost enough to drive me crazy, but I will overcome it and yet make my way through this world, in a way which will be a blessing in the memory of my dear ones.” Upon his release from jail in April, the San Francisco Chronicle (April 20, 1901) further embellishes on his family’s plight in an article headlined “Victim of Many Misfortunes”: “Since his incarceration his brother’s wife has been assaulted by a negro at Paris, Ky., and the negro burned at the stake.” Those of you who follow this blog know that is a false statement, yet there appear to be no bounds for newspapers at the time when invention fosters sensationalism that sells papers. Richard T. Board Jr., with his privileged upbringing, regular access to men of power, and his recognition of the authority of the press to shape a story, can construct his family’s narrative, and our nation’s recorded history, through a series of glib conversations and eloquent letters. Ultimately, what was Richard’s response to his “many misfortunes”? As seemed to be the Board family ritual, he took the next train out. The next month, May 1901, he leaves Kennett for Los Angeles to work for the Sierra Railway Co. of California, which was then engaged in a large tunnel project. Accounts seem to indicate he spent a relatively quiet year or two there, working as an assistant agent and a car cleaner, before returning to the mines in northern California, and to his life of petty crime.

5 Comments

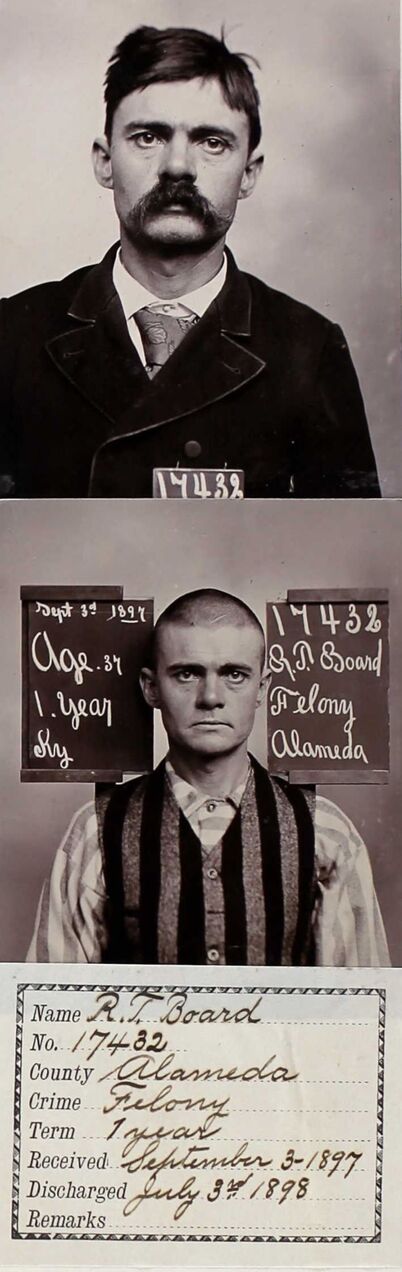

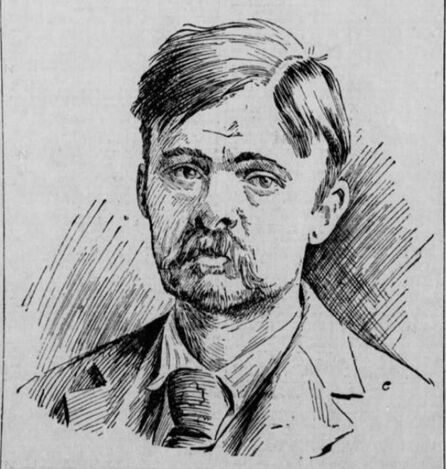

Richard T. Board’s intake photo (top) and discharge photo (bottom) from San Quentin Prison. His offense is listed as “felony”—probably a clerical error since he was convicted of forgery. Richard T. Board’s intake photo (top) and discharge photo (bottom) from San Quentin Prison. His offense is listed as “felony”—probably a clerical error since he was convicted of forgery. This is the second in a series of blog posts about my great-great uncle Richard T. Board, the uncle of my already infamous grandfather William Lyons Board. (Read Part 1) Many thanks again to my friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard for discovering yet another curiously dissipated ancestor of mine. It is only because of her extensive research that I am able to share these startling stories with you. Nine years after being released from federal prison in Illinois, where he served two years for stealing a $163 money order from a mail service train on its way to Santa Fe, N.M., Richard T. Board Jr. sits next to his attorneys in another courtroom, this time in Alameda County, Calif., with a baby in his arms. It’s August 1897. During the trial, he does not deny that he endorsed a $50 check with his kindly benefactor’s name—a woman who had provided him shelter on her ranch when he was destitute—and then asked a 15-year-old boy he approached in the street to have it cashed at Kahn Brothers shoe store. But he claims that he was driven to this criminal act only by the dire circumstances of his poverty. After losing his job at Judson Iron Works, he had been struggling to find work and was searching for a way to feed his family, including his wife, there in the courtroom anxiously watching the proceedings, and the baby he continues to hold. He also makes a point to mention that he and his wife, Mary, had recently lost another child. How had Board gotten into this predicament? After being discharged from the Army in July 1894, he had remained in the San Francisco area and married Mary Hannah Beadle in December. He may have done a brief stint in the Marine Corps, serving at the Navy Yard on nearby Mare Island. It’s more certain that he joined the National Guard in April 1896 and was honorably discharged in September. Now in his mid-30s, these enlistments may well have been his best shot at a steady paycheck. The U.S. military services were evidently happy to accept a convicted felon in their ranks. But now he finds himself in yet another courtroom facing yet another term in prison. Newspapers across the country are covering this trial, just as they did his first. Board is repeatedly identified as “a protégé of ex-Senator Joe Blackburn of Kentucky [whose] father was for thirty years clerk of the United States circuit court of Kentucky.” [The Omaha Evening Bee, 04 July 1897] No newspaper mentions the younger Board’s multiple arrests for forgery or theft. None mentions his previous incarceration. Board tells them exactly what he wants them to print, which is whatever he thinks will help his case. In the end, the judge—clearly affected by the pathos of the situation before him—gives Board the minimum sentence for his offense. Board is sent to San Quentin for one year. Is it possible that the judge was not aware that Oakland police had a warrant for Board’s arrest a year earlier for similar crimes: sending boys into butcher shops and breweries to cash checks and thus defraud the proprietors? According to the San Francisco Call, a string of these crimes had again been reported in the weeks leading up to Board’s arrest in June. His forgery of the check in the shoe store was not an isolated crime committed in a moment of desperation. Nevertheless, it’s almost certain that the judge was aware of who Mary Beadle Board was. Just as it’s almost certain that Richard Board knew who Mary Beadle was long before he ever left St. Louis for his Army stint in San Francisco. Was it mere happenstance that he landed in the very city where one of the nation’s most sensational trials was taking place? Or did Richard Board arrive in California with designs on the aspiring teenage heiress Florence Blythe or her nurse, Mary Beadle? Let’s jump back a bit and pick up Mary’s story.  Heiress Florence Blythe Hinckley, from the San Francisco Chronicle, 01 December 1892. Heiress Florence Blythe Hinckley, from the San Francisco Chronicle, 01 December 1892. On April 4, 1883, real estate tycoon Thomas Henry Blythe died suddenly at his home in San Francisco at age 60. A native Englishman of some reserve and mystery, he had amassed a $4 million fortune and owned vast property in San Francisco, San Diego, and Mexico, as well as a mining property in Nevada. Upon his death, more than 100 women came forward claiming to be his widow or his heir. Ten-year-old Florence Blythe, whose family asserted she was Blythe’s illegitimate daughter and sole legitimate heir, was brought to California from her home in England shortly after her father’s death by her maternal grandfather, Mr. James Crisp Perry, his wife, Kate Beadle Perry, age 30, and her sister, Mary Beadle, age 24. Mrs. Kate Perry was frequently identified in the press as Miss Blythe’s “guardian” and Mary Beadle as her “nurse” or as a servant in the Perry household. Initially, no will could be found, and the courts wrestled with Blythe’s estate until the matter was sent to trial, six years after his death, on July 15, 1889. A verdict would not be reached in the complicated case until 1895. Five days after the trial began, one of the attorneys for Florence Blythe announced that he had located Mr. Blythe’s missing will in Los Angeles, where it had been stashed by Mr. Blythe’s housekeeper, who claimed after his death to be his widow. The will bequeathed the entire estate to his young daughter, Florence Blythe. The attorney also had letters written by Mr. Blythe to his daughter and his daughter’s mother, many which had contained money for her support. The almost cartoonish melodrama of the trial was breathlessly covered by newspapers across the country, including in St. Louis, where Richard Board could follow the lurid details in the Globe-Democrat after he got out of prison. He likely was familiar with all the major players, including Mary Beadle, who with her older sister and brother John were put on the stand to testify about their history with their young charge, Florence Blythe, when they all lived in England. When Richard Board lands in San Francisco for a stint in the Army in April 1892, he may have had designs on the young heiress herself. But on June 22, 1892, 19-year-old Florence Blythe surprises her loyal followers by marrying the boyish Fritz Hinckley, 23, heir to his father’s foundry business. (Fritz dies tragically five years later after suffering appendicitis while traveling with friends to Salt Lake City.) So perhaps Richard then sets his sights on Mary, who expects to receive a sizable sum ($10,000-$15,000) for her services working for the Perry family once the estate is settled. And on December 3, 1894, Richard marries her. But things don’t go as planned for the newlyweds. Florence Blythe Hinckley disapproves of the marriage (because Board had made overtures to her?) and casts Mary aside. Florence’s grandfather, James Crisp Perry, dies and his wife Kate, Mary’s sister, remarries. The Boards find themselves abandoned by Mary’s family and penniless. Before her husband’s trial begins, Mary announces she intends to sue the Blythe Hinckley estate and her sister for the money she feels she is due. A few months after Board’s trial, while Richard remains incarcerated in San Quentin, Mary’s sister Kate, now Mrs. John E. Byrne, receives $250,000 from the heiress. From all we know, Mary patiently waits for her husband’s return from San Quentin. Three months after his homecoming, Richard Board is working in the nitrate house at Judson Dynamite and Powder Works in Berkeley when there is an explosion in the adjoining mixing room. The building is destroyed and the two men who had been in the mixing room are “blown to atoms.” [Evening Sentinel, Santa Cruz, Calif., 24 October 1898] Board is thrown 60 feet but receives only lacerations. Only a wooden bulkhead had separated him from the 200 pounds of gelatin (guncotton, nitroglycerine, potassium nitrate, and other ingredients) that was being made into dynamite next door. Board described his experience to a reporter from the San Francisco Call’s Oakland office: “A little after 8 o’clock the explosion occurred, but it came so suddenly that I hardly heard anything. In fact I did not have time to think before I was in the air, with lumber and dirt flying all about me….I cannot describe the sensation…for it was most peculiar. First I seemed to be falling into a deep abyss, then the walls seemed to all cave in and I was drawn right up into space.” After yet another encounter with fickle fate, Richard T. Board Jr. walks away nearly unscathed. Soon his remarkable luck will protect him once again, while tragedy befalls all those around him.  Richard T. Board Jr., from a drawing that appeared in the San Francisco Call in 1897. More on that story in Part II. Richard T. Board Jr., from a drawing that appeared in the San Francisco Call in 1897. More on that story in Part II. This is the first in a series of blog posts about my great-great uncle Richard T. Board, the uncle of my already infamous grandfather William Lyons Board. Many thanks to my friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard for discovering yet another curiously dissipated ancestor of mine. It is only because of her extensive research that I am able to share these startling stories with you. The Republicans were outraged. Couldn’t this administration appoint any officials who weren’t already corrupt or proven criminals? Grover Cleveland, the newly elected president, was the first Democrat to sit in the White House since the Civil War, and newspapers across the country railed against his inept hiring practices. The St. Albans [Vermont] Weekly Messenger repeated what was evidently a common refrain: “Another jail bird appointed to office by the democratic administration.” The article goes on to say that soon after Richard Board, age 25, was appointed clerk for the Rincon to Deming, N.M., route of the U.S. Railway Mail Service, prominent citizens in his hometown, Harrodsburg, Ky., notified the federal government that “Board was under three indictments for forgery, and had been three times arrested in Cincinnati for getting money under false pretense, once in Texas for robbery and twice for theft in Kentucky.” I have not been able to corroborate all these claims. Nonetheless, how on earth had young Richard Board gotten this plum assignment in the 15-year-old Railway Mail Service? Richard T. Board Jr. was the eldest of three sons of Richard T. Board Sr., the highly respected longtime circuit clerk in Mercer County, Ky. (county seat, Harrodsburg). The son had worked as the deputy clerk to his father for at least a couple of years. Richard Board Sr. was well known among Kentucky’s political powerbrokers. The First Comptroller of the Treasury in the Cleveland administration was Hon. Milton J. Durham, a native of Danville, Ky., one county south of Mercer. Durham had evidently sponsored Board’s appointment upon the recommendation of Kentucky’s Democratic U.S. Senator Joe Blackburn (younger brother of Kentucky Governor Luke Blackburn, whose term had ended in 1883). It probably didn’t hurt that the assistant postmaster general during the Cleveland administration was Adlai Stevenson, a Kentucky native who evidently was eager to fire Republican postal workers and replace them with Southern Democrats. This was the machine behind young Richard’s federal appointment. Somewhere along the way, no one bothered to ask about his character. Two weeks after Board was named to the post, Comptroller Durham, according to the St. Albans newspaper, “got a lively letter from a friend in Kentucky, reciting Board’s criminal record in full. The letter concludes with the prediction that Board would steal something before he had been in the service a month. The prediction was fulfilled. Before the warning note was written Board had stolen a money order for $163.” Board had been appointed to the position on July 7, 1885, dismissed on July 30, and, on August 17, was arrested in St. Louis where he previously had been living with his wife of eight months, Fannie Mace. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat claimed he had illegally used his Railway Mail Service transportation card to travel back to Missouri after his dismissal. Board was unable to pay the $1,500 bail and was remanded to jail in St. Louis. After being transferred to a Santa Fe jail, he stood trial in Socorro, N.M., in March 1886 and was found guilty of robbing a registered letter from a train heading to Santa Fe. Never one to blame himself for his misfortunes, Board evidently claimed, and The Sierra County Advocate of Kingston, N.M., reported, that “His downfall [was] attributed to an immoral female.” After the trial, federal marshals brought Board back to St. Louis and he was delivered to Southern Illinois Penitentiary at Chester (now Menard Correctional Center), 60 miles southeast of St. Louis, to serve a two-and-a-half-year term. On February 7, 1888, while his oldest son was still in prison, Richard T. Board Sr. died of a paralytic stroke at age 62. According to the Stanford, Ky., Interior Journal, he had been “on the street apparently well an hour before.” Newspaper documentation shows that Richard T. Board Jr. had indeed been arrested multiple times for forgery and theft before he was incarcerated in Illinois. Reports indicated that his father had done all he could to honor his son’s debts and rescue him from his scrapes with the law. In September 1883, records show Richard Board Jr. had been arrested in Cincinnati for forging his father's name to a check at the National Saloon. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, “In his pocket was found a touching letter from his brother in Harrodsburg, Ky., begging him for the sake of his folks to behave himself.” That brother would be my great-grandfather, William Ellery Board, father of William Lyons Board. A few months later, in January 1884—while working as a bookkeeper in St. Louis, a few months before marrying Fannie—Board passed a false $10 check written on a Harrodsburg bank to the Pacific Express Company. In lieu of an $800 bond, he went to jail. I can only assume that Richard Board Jr. returned to his wife in St. Louis after he was released from prison on May 4, 1888. By June 1892, however, Fannie had filed for a divorce from Richard Board, accusing him of “brutality and general indignities,” according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. By then, Board was already gone. On April 30, 1892, at 31 years old, he had enlisted as a private in the Army and was stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco. Richard Board Jr. had landed in the wild west, and he would spend the next 25 years wreaking havoc up and down the coast, leaving tragedy in his wake. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed