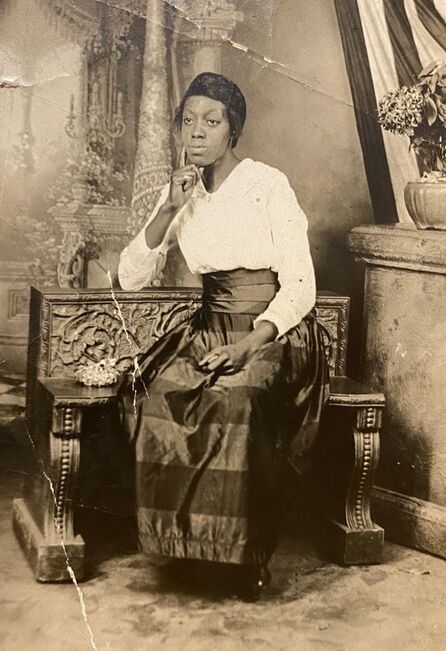

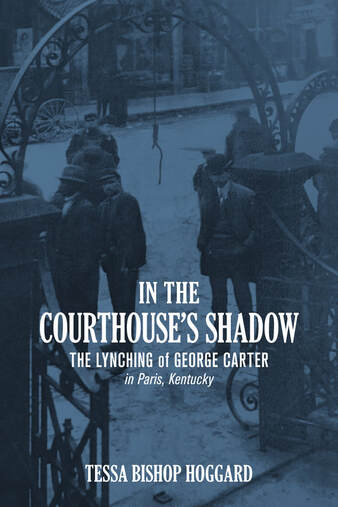

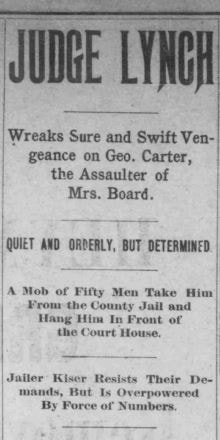

Katie Carter, the younger sister of George Carter and the grandmother of Jim Bannister. George Carter was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901. Photo provided by Jim's daughter, Cheryl. Katie Carter, the younger sister of George Carter and the grandmother of Jim Bannister. George Carter was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901. Photo provided by Jim's daughter, Cheryl. On February 23, 1900, Rep. George Henry White (R-N.C.), the sole Black U.S. lawmaker at the time, gave an impassioned speech on the House floor about the antilynching legislation he was proposing. The bill would make mob violence that resulted in the victim’s death a federal crime of treason to be tried in U.S. courts. White had felt compelled to act after witnessing the bloody Wilmington, N.C., race riot a little over a year before, during which a mob of white locals toppled the city’s multiracial government and ruthlessly murdered an estimated 60 innocent Black citizens. After White’s speech, his fellow congressmen applauded his words but failed to pass the bill out of committee. Thirty-five years after the Civil War, Southern devotion to states’ rights was still paramount. White called out some of his colleagues who had spoken against heinous lynchings in their own communities. In White’s view, these legislators would not countenance federal legislation because “this would not have accomplished the purpose of riveting public sentiment upon every colored man of the South as a rapist from whose brutal assaults every white woman must be protected.” [Washington Post, February 21, 2020] A year later, on February 11, 1901, a determined mob of local townsmen hung George Carter in front of the Bourbon County Courthouse in Paris, Ky. His crime? According to news reports: an attempted purse snatching. According to rumor and innuendo: rape.  My great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. My great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. The woman George Carter allegedly accosted was my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Board. The eight-year-old boy who identified Carter as his mother’s assailant was my maternal grandfather, William Lyons Board. There are reasons to question whether George Carter was indeed the man who assaulted my great-grandmother. There was no trial, no presentation of evidence. There was almost certainly no capital crime. In her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky, Paris native Tessa Bishop Hoggard scrutinizes the contemporaneous documentation and then offers a riveting account of the lead-up to the encounter with my great-grandmother and its chilling aftermath. The hanging also plays a pivotal role in the novel I wrote about my grandfather, Next Train Out. Of course, no one in that Paris, Ky., mob was ever identified or arrested. No one was charged or convicted of murdering George Carter. There was no federal hate crime or antilynching law on the books, because Congress had failed to act the year before. It was not until 1920 that “Kentucky became the first southern state to pass an antilynching law.” [John D. Wright Jr., “Lexington’s Suppression of the 1920 Will Lockett Lynch Mob,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 84, no. 3 (1986): 263-79.] This month, 122 years later, after 200 failed attempts, Congress finally succeeded in passing the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, named in honor of the 14-year-old boy who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. After President Biden signs the bill into law, a lynching resulting in death or serious bodily injury can be prosecuted as a federal hate crime punishable by up to 30 years in prison. It’s too late for George Carter, of course, or for the estimated 2,000 people who were lynched in this country after White’s original bill failed. But perhaps it’s a sign that our nation’s citizens are finally ready to take some initial steps toward ensuring justice prevails when racial hate crimes are committed. Just last month a Georgia jury found the three white men involved in Ahmaud Arbery’s murder guilty of federal hate crimes. The next day the three Minneapolis police officers who remained inert as Derek Chauvin slowly killed George Floyd were all found guilty of violating Floyd’s civil rights. It may feel like way too little way too late, but perhaps we can sense a slight rebalancing of the scales of justice. Perhaps we are moving at a snail’s pace toward that more perfect union where all men and women truly are created equal. Despite current efforts in statehouses across the country to restrict discussions of our nation’s documented history relating to racial injustice and oppression, perhaps these concrete actions are signs of movement in the opposite direction, toward transparency and a more honest reckoning of our past. We all need to feel uncomfortable about the atrocities that have been committed in this nation to buttress unequal power structures. We need to feel shame. And then we need to take action to address the lingering institutions and sentiments that perpetuate these injustices. Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill, the longtime champion of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, said after the bill passed: “Lynching is a longstanding and uniquely American weapon of racial terror that has for decades been used to maintain the white hierarchy…. [This bill] sends a clear and emphatic message that our nation will no longer ignore this shameful chapter of our history and that the full force of the U.S. federal government will always be brought to bear against those who commit this heinous act.” [NPR, March 7, 2022] Bill signedOn Tuesday, March 29, 2022, President Biden signed into law the Emmett Till Antilynching Act. Till’s cousin, Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., the last living witness to his abduction, said in response, “Laws make you behave better, but they cannot legislate the heart.” Let’s hope the hearts of all Americans are slowly recognizing the injustices that have stained our nation since its inception. eventOn Saturday, March 26, 2022, Tessa Bishop Hoggard and I participated in a Zoom virtual conversation hosted by the Paris, Ky., Hopewell Museum. We discussed the 1901 lynching of George Carter and how that dark episode prompted both of us to write our books. Connecting with Tessa ultimately led to my friendship with George Carter’s great-nephew, Jim Bannister.

4 Comments

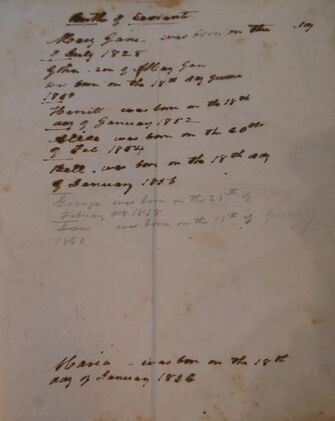

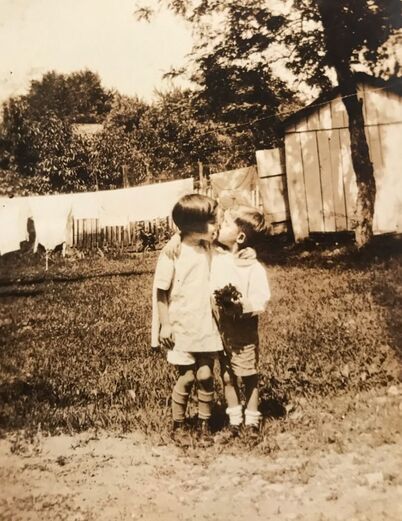

The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. As I started working on Next Train Out, I knew that racial conflict had to be a theme of the novel. It seemed clear to me that the trajectory of Lyons Board’s life had to be predicated in part on his role, as an eight-year-old boy, in having a Black man lynched in his hometown, Paris, Ky., in 1901. As I researched the various cities and towns where my grandfather eventually lived, I found plenty of instances of racial unrest in their histories: mob violence, riots, lynchings, the obliteration of sections of towns where Blacks lived and prospered. Soon I began to better grasp the bigger picture, that the whole country was awash in deadly racial conflict just after World War I, when Black soldiers returned home expecting opportunities and respect in return for serving their country in the trenches in Europe. Instead, they found resentment and violence stoked by the belief among some white citizens that these returning veterans threatened their jobs and their status in the community. I learned about the Red Summer of 1919, which made me realize how widespread these race problems were. These confrontations were not isolated to the Deep South. They erupted in our nation’s capital, in Chicago, in New York and Omaha—in at least 60 locations from Arizona to Connecticut. How this anger and suspicion manifested itself in towns like Corbin, Ky., and Springfield, Ohio, are part of Lyons’ story. As we all now know, an area referred to as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Okla., waited until 1921 for its turn at center stage. On June 1, after 16 hours of horror, more than a thousand homes and scores of businesses had been incinerated. Somewhere between 100 and 300 people had been murdered. Thousands of Black survivors were then corralled into a detention camp of sorts and assigned forced labor cleaning up the mess the violent white mob had created. Before June 2020, when President Trump landed in Tulsa for a campaign rally originally scheduled to take place on Juneteenth, few Americans knew the lurid history of Black Wall Street. The facts had been suppressed, kept out of classrooms, out of the news, out of polite conversation. Black families in Tulsa passed down stories of violence and terror and escape—or stories of family members never seen again, their fates unknown. Few public officials dared recognize what had happened to all those people and their livelihoods and their property and their wealth. This year, on its 100th anniversary, the entire nation has been awakened to Tulsa’s tragic history. LeBron James produced a documentary—one of many. Tom Hanks wrote an op-ed. HBO made its Watchmen series accessible to more viewers. News forums of all types reported on the anniversary. Survivors of the massacre—all more than 100 years old--testified before Congress and met with President Biden. Under the leadership of Tulsa’s young white Republican mayor, G. T. Bynum, archaeologists have resumed the search for mass graves that had finally begun last summer. How a community like Tulsa now, finally, begins to reckon with its history is significant for all of us. We as a nation, as a collection of human beings, must break the silence we have permitted ourselves for generations and acknowledge how gravely we have wronged indigenous peoples, Blacks, and other minorities. How we blithely destroyed their culture, their history, their identities, and their lives. Acknowledging the truth is a start. Reporting historical facts is essential. Engaging in respectful, compassionate, and sensible discussion can prompt healing. Some communities—and even the U.S. Congress—are now beginning to discuss what reparations might look like. Other communities first need to simply acknowledge both the shame and the pain that have churned for decades among their citizens. When I first met with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of the man lynched because of an alleged incident with my great-grandmother, he made it clear that it was the silence that weighed most heavily on him. He had tried to learn more about the lynching of George Carter, but no one would talk about it. His elders wouldn’t talk about it. The Black community wouldn’t talk about it. Fear and shame and ongoing oppression had kept everyone close-mouthed for generations. The emotional damage accrued. The human damage. The not knowing. The not understanding.  With her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow, Tessa Bishop Hoggard provided the key that Jim needed to open the door to his family’s history. She pulled his story out of the shadows. Jim has told me repeatedly that he feels an extra spring in his step now that he knows the facts. He has found a peace that had eluded him all of his eighty years. In her interview with Tom Martin on WEKU’s Eastern Standard program this week, Tessa said, “As we peer into our history, hate crimes were a common daily occurrence….Accountability and consequences were absent. There was only silence. This silence is a form of complicity….Today is the time for acknowledgment and healing. Let the healing begin.” (Listen to the 10-minute interview.) We have to acknowledge our difficult history. We have to face what happened. And then we have to consider the steps, both small and large, that we can take to heal the wounds that will only continue to fester if we stubbornly ignore them.  This year, on the morning of Juneteenth (Saturday, June 19), I’ll have copies of Tessa’s book and my novel available for sale at the Lexington Farmers Market at Tandy Centennial Park and Pavilion in downtown Lexington, Ky. In August 2020, the citizens of Lexington agreed to rename Cheapside Park, the city’s nineteenth-century slave auction block and one of the largest slave markets in the South, the Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park, honoring the freed slave who did masonry work for many of Lexington’s landmarks, including laying the brick for the nearby historic Fayette County courthouse, built in 1899. One of the organizers of the “Take Back Cheapside” campaign, DeBraun Thomas, said at the time: “Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park is one of the first of many steps towards healing and reconciliation.” Fittingly, I’ll be at the Farmers Market as part of the Carnegie Center’s Homegrown Authors program. Tandy had a hand in the construction of Lexington’s beautiful neoclassical Carnegie Library on West Second Street in 1906, now the home of the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning. If you’re in Lexington that morning, stop by and we can continue this conversation.  Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. It’s Black History Month, so it’s time for more reckoning. I have written freely in this blog about my family’s role in the lynching of a Black man, George Carter, in Paris, Ky., in 1901. I have written about my horror in learning about that incident. I wrote last summer about my rising fury at the unending injustice in this country that has led to the unconscionable loss of Black lives, tragedies that have been ongoing for generations but which have become more public with the advent of cell phone videos. I remain angry and disgusted with the lack of progress on the underlying issues that allow this to continue. I hope to write more about that before February comes to an end, and we give ourselves permission to stop thinking about these things until next February. Right now, however, I need to talk about the family Bible. I remember this Bible being displayed on a dropleaf cherry table in front of the picture window in our living room in Lawrenceburg, Ky., when I was a child. It was an enormous, handsome, heavy book, in good condition for a book of its age. I remember flipping through it; I remember noticing handwriting on some of the pages. But I don’t believe I could have told you what branch of my family it represented or anything about the people whose births and deaths and marriages had been noted. Recently a family member shared some photos she had taken of those pages. I immediately recognized that the Bible was yet another relic of my missing grandfather’s family, the grandfather who abandoned my mother shortly after her birth. The Bible was published in 1848, so the Bible first belonged to my grandfather Lyons Board’s grandparents, Dr. L. D. Barnes and his wife, Mary Parker Roseberry Barnes, of Paris, Ky. After all the research I—and others—have done into that family over the past ten years or so, I now recognize the names. Those of you who have read Next Train Out might, too. There’s the marriage of Dr. Barnes’ daughter, Mary Lake Barnes, to William Ellery Board, originally of Harrodsburg, in 1888. There’s the marriage of their only surviving son, William Lyons Board, to Nell Hardeman Marrs of Lawrenceburg, in 1920. There are the births—and the deaths—of all the children who didn’t live to adulthood, or didn’t even survive infancy.  And there are the births of the “servants.” The servants are identified only by first names: Mary Jane, John, Harriett, Alice, Bell, George, Dan, and Maria. The listing is separate from the “Family Record” listed in a fine hand on decorative pages. The handwriting on the servants page is less careful and difficult to read. It grieves me that I may not have all of the names correct. Another thing we have learned this year is how important it is to say their names. All of the servants were born between 1828 and 1860. All were born, I have to assume, into slavery. I don’t know that for certain, of course, And it’s possible they had been freed by the time they were listed in the family Bible. But any other scenario is hard to imagine in central Kentucky before the Civil War in a family of some status living in a county with a large population of slaves working expansive agricultural land. The fact that they are included in the Bible makes me want to believe that they were indeed considered members of the household and were treated gently and respectfully and were well loved by the Barnes family. None of that excuses the fact that some or all of them were at some point the property of the Barneses. I had already discovered some time ago that at least three of the four branches of my family once owned a small number of slaves, probably all doing domestic household work. I had already reckoned with that in some small way. It was not a surprise to discover this listing of the Barnes family servants. But it remains painful to see the evidence handwritten in such a personal way in the family Bible. Many of us from the South share a similar family history. It’s remote to us now. We’re talking about more than 150 years ago, after all. Nonetheless, I feel it’s important not to deny our intimate connections—no matter how tenuous, no matter how seemingly innocent—to the national shame our country has to bear, and bear witness to. My family played a role. The Bible tells me so.  Mary Marrs Board and David Caddell. Photo provided by Anne Simmons. Mary Marrs Board and David Caddell. Photo provided by Anne Simmons. Over this year of disruption and isolation and sorrow, I have heard many people say they intended to dedicate some of the time they were stuck at home to sorting through family photos. While I seem to have frittered away all those months with nothing to show for it, some of you apparently followed through. A week ago I was delighted to receive an unexpected text from a former classmate and old friend, Anne Moffett Simmons, who I hadn’t heard from in decades. Attached were photos that she and her sister had discovered while going through family albums. One photo shows my mother, around age six, with her arm around the younger David Caddell, Anne's uncle, as he sneaks a kiss. In another photo, there's my mother sitting next to her friend Dot (Dorothy) Caddell, Anne’s mother and David's twin sister. David stands to the left, looking a little sheepish, and my mother’s cousin, George McWilliams Jr., is on the right, seemingly disinterested in all the commotion. I cannot explain the sheer joy that photo elicited. There was my mother, surrounded by her pals and playmates when she was a very young girl, holding what appears to be a bouquet of flowers. She’s smiling at the person taking the picture, whom she seems to completely trust to capture her pleasure in the moment. Dot looks like she can barely tolerate sitting still for these ridiculous shenanigans and is already plotting her next move. The boys stand as unwilling sentinels on either side. It’s only since I began working on Next Train Out that I have become more fully cognizant of the depth of sadness my mother endured in her lifetime. The loss of her husband in mid-life was just the final blow. There had been the loss of two children and her mother while she was hundreds of miles away from family. The permanent absence of her father who had never bothered to contact her after disappearing shortly after she was born. And, after returning to her hometown to raise her two daughters, the eventual recognition that her old friends had largely moved on with their lives. While I can recall moments when my mother laughed or acted a little silly, those were few. By the time I was old enough to pay attention, she seemed more commonly somber and somewhat melancholy. It has taken me a lifetime to reflect on why that was. But in this photo she radiates happiness. Happiness to be seated beside her friend Dot. Happiness that she's the focus of someone's attention. Happiness that someone wants to take her picture. I wish I could ask that little girl what she’s thinking. As you come across family photos while sorting through the detritus of your rich and complicated lives, I encourage you to consider who else might relish a glimpse into the moments captured by the camera. Because our connections with others have been so restricted over the past year, many of us are aching for a little time with those we love. You might be surprised how healing it can be to have your emotions stirred, even by a black-and-white photo from a time long ago.  A scene from an orphan train. Photo provided to CBS News by the National Orphan Train Complex Museum and Research Center. A scene from an orphan train. Photo provided to CBS News by the National Orphan Train Complex Museum and Research Center. Once I had decided to write a novel about my grandfather, I knew that I wanted to hew to the facts of his life as closely as possible. That, of course, required extensive research—research into the public records that revealed his movements and actions, research into the other people who inhabited his world, research into the cities where he made his home, and research into the history and culture of the United States between 1900 and 1942. For me, one of the most difficult aspects of writing Next Train Out was knowing when it was time to stop researching and start writing. In the end, external circumstances pushed me to abandon my feeble efforts to educate myself and find the courage to put words on a page. I had enrolled in the Author Academy at the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Ky., and my mentor wanted to see a fledgling manuscript. Although there was still research I wanted to pursue, I stopped making that my emphasis and turned my attention to creating a fictional world. Occasionally, of course, I still had to stop writing and look up some historic detail or spend a little time pursuing a lead that had just turned up. Sometimes the leads that most intrigued me were unfortunately set aside as new distractions demanded my attention. Earlier this summer I finally picked up the phone to pursue one of those leads. I had some notes that indicated that, in 2000, Effie Mae’s great-granddaughter had lived one county north of my home. I didn’t know if that was still the case, or whether the contact information I had for her was still valid. But since I finally had some time, I was determined to see if I could find her. Eventually, one of the phone numbers I tried rang through. “Hi. My name is Sallie Showalter. Is this Storme Vanover?” I asked tentatively. “Yes.” “Ms. Vanover, I live nearby in Scott County, and I recently wrote a novel about the woman I believe was your great-grandmother—Effie Mae Frady.” “Yes, that’s right. Effie Mae was my grandmother Edna’s mother.” “Well, my grandfather was married to your great-grandmother and, if you’re interested, I’d love to meet you and give you a copy of the book.” With that prompt, Storme, who was driving her car at the time, began to share some of her family’s story. Last week I met with her for an hour in her home in northwestern Grant County, and she graciously filled in more of the details. Storme is indeed the granddaughter of Effie Mae’s younger daughter Edna (whom I call Eileen in the book). I knew from my research (or rather, from Chuck’s research) that Edna had eventually moved to Michigan and married there. Storme was born in Detroit. What I did not know was what happened after Effie Mae left her three older children in Kentucky, including Edna, when she and her youngest son Doug moved to Cincinnati. The 1920 census confirms that Effie and all her children were living with Effie’s brother in the Logmont coal camp. But I had to imagine what happened to the three older children Effie Mae left behind. In my naiveté—which reflects the ease of my own life—I decided that the children stuck together and successfully navigated their way to adulthood. As I look back on it now, I created a rosy moving picture story, complete with a softening scrim that subdued the hardships they must have endured. In reality, as Storme shared with me, Edna, at some point after her seventh birthday, was put on an orphan train and landed in a Catholic orphanage. No one knows where that orphanage was, but I was distressed to read the stories of neglect and abuse at a number of those institutions in Kentucky and elsewhere. According to Storme, Edna eventually initiated steps to take her vows as a nun. But her plans were derailed when she became pregnant by a young priest-in-training—or was it a truck driver? Edna's story would vary. Wherever the truth lay, it seems that Edna’s older sister Vivian (I call her Valarie in the book) cared for baby Shirley for some time, perhaps contrary to Edna's wishes. Edna eventually moved to Michigan, and Edna and Shirley were reunited when Shirley was six. The father of the child had no further role in their lives, and Edna and Vivian never spoke again. This is just a glimpse into a family story full of tragedy and mésalliances as well as love and loyalty. That story is Storme’s story, and I will leave it to her to tell. But I’ve thought about what I’ve learned from her about the fate of Effie Mae’s children. If I had reached out to Storme while I was writing the book, would I have portrayed Effie’s story any differently? Did Effie Mae know what happened to Edna? To Vivian and Lynn, her older son? Did Effie herself put Edna on that train? Or was that Edna’s father, whom Edna was devoted to? Or was it her uncle, who had taken the whole family in? I didn’t pursue a lead while I was writing my grandfather’s story, and I now know more of the truth underlying his tale. That truth doesn’t change the work of fiction I created. But it does deepen my understanding of the lives interwoven with his own, and it reveals the hidden complexities of all our stories.  How I’ve spent my summer marketing Next Train Out. Photo by Rick Showalter. How I’ve spent my summer marketing Next Train Out. Photo by Rick Showalter. As traditional book fairs, author readings and, yes, book launch parties remain taboo, digitally savvy authors come up with creative ways to alert likely readers to their new books. The rest of us rely on friends, family, and colleagues to spread the word. Once the pandemic tightened its sticky little fingers around our collective throats, I pretty much gave up on marketing. I tried to focus on the blog, just to stay in touch with all of you. But I largely threw up my hands and said, “It’s God’s will.” Then I sat on my butt and ate bonbons. Slowly, however, as the initial shock of the lockdown lifted, the wheels of the old network began to grind. Thirty years of job-hopping started to pay off. A couple of folks I exchanged pleasantries with during my working days felt sorry for me and offered to help. First, Tom Eblen, formerly with the Lexington Herald-Leader and now the literary liaison with the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Ky., reached out to me about doing an online reading to post on the Center’s Facebook page. Being the Luddite and contrarian I am, I’m not on Facebook. But I figured millions are, so surely two or three potential readers might become bewitched by the tale of Lyons and Effie Mae. I grumblingly agreed. After a couple of technical glitches, I managed to submit a seven-minute reading that suited his purposes. Then Tom Martin poked his head up from all the reporting the pandemic had generated for his weekly radio program on WEKU, Eastern Standard. Tom and I had planned to do this interview in April, but waiting until July gave me plenty of time to rest up before I had to perform again. Tom is a consummate interviewer—and an excellent editor. He can make anyone sound good, thank goodness. I know some of you caught the original airing of this interview on July 16. Now I figure if I sit patiently in my office—or on my dock—maybe another opportunity or two will come. Perhaps I’ll even sell a couple more books. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to lean on the excuse that there’s not a damn thing I can do to market this book during a pandemic. Coming upOn Thursday, July 30, at 11 a.m. on WEKU’s Eastern Standard, Tom Martin will present his remarkable summary of the conversation I had on July 15 with George Carter’s great-nephew, Jim Bannister. Listen to a preview. If you can’t catch the original airing, it will be available from Eastern Standard’s archives afterwards. I’ll write more about this experience for Clearing the Fog soon. That post will include links to the WEKU broadcast and to various newspaper articles about the conversation.

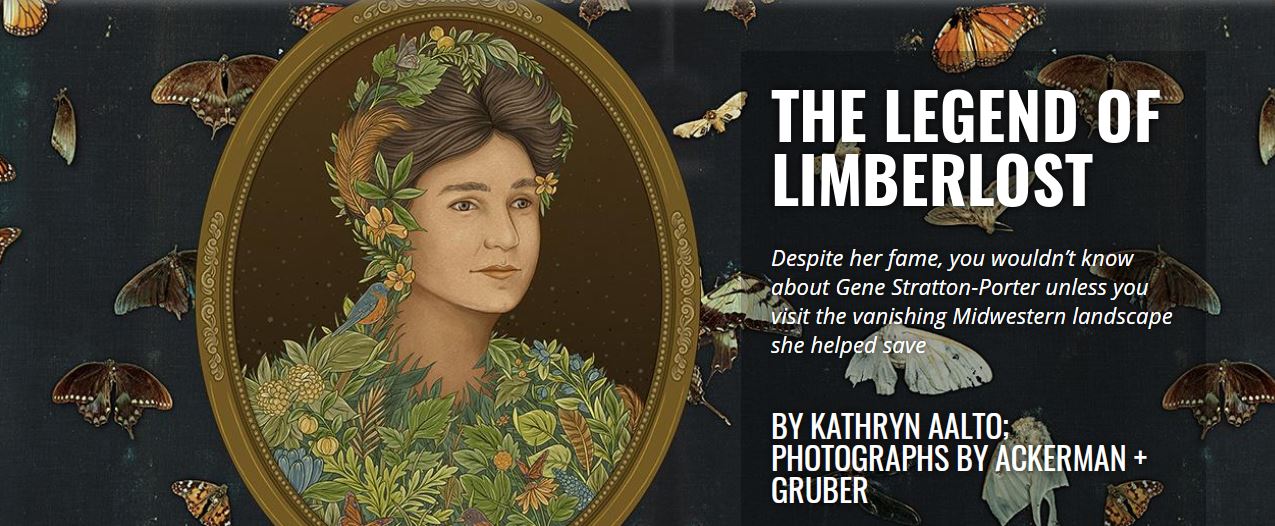

Effie Mae’s son Doug served on the USS Canopus, a U.S. Navy submarine tender, during the 1930s. Doug died in 1988, three years before my mother. Effie Mae’s son Doug served on the USS Canopus, a U.S. Navy submarine tender, during the 1930s. Doug died in 1988, three years before my mother. Yesterday I talked with Effie Mae’s granddaughter. Doug’s daughter. Many of you who have read Next Train Out know that the novel is based on the life of my grandfather, William Lyons Board. You know that most of the major events in the book are factual, according to historical records uncovered over years of research. But you may not have fully understood that Effie Mae, the other narrator in the novel, was also drawn nearly completely from records of her life. The same goes for Doug, her youngest son. Some years ago my friend and collaborator, Chuck Camp, found Kathleen, Effie Mae’s granddaughter, in the Washington, D. C. area. He talked to her a few times, pressed her about what she knew about her grandmother, who had died before she was born. The details were few, but Kathleen was able to relay some sense of the warm relationship her dad had with both his mother, Effie Mae, and his stepfather, “Bill” Board. Chuck and I had tried to arrange a trip to meet Kathleen and interview her in person, but we kept bumping into scheduling obstacles. Eventually, I shifted from a focus on research to writing the novel, and I threw all my energy into getting words down on the page. All along, of course, I knew Kathleen was out there, and I hoped to finally meet her. I had planned to invite her as a guest of honor to the book launch party that had been scheduled for April. When the coronavirus forced us to abandon those plans, I once again turned my attention to other things. So it wasn’t until yesterday that I picked up the phone and “dialed” the number I had for her, not knowing if it would still be valid. As I was leaving a message, she picked up. We had a delightful conversation, and I am now more eager than ever to visit her in person—whenever that is possible. I confirmed some things we have in common: she and I both grew up in Baltimore, and we both spent at least part of our careers as technical writers. (One distinction: she is still working and loves her job.) In a brief email I sent to her afterwards, I suggested that perhaps we are “step-grandsisters,” her grandmother having married my grandfather. I have mailed her a copy of the book, and I look forward to discussing it with her after she has read it. No doubt much of it will feel familiar to her. She may also learn some things about her grandmother’s life. And I’m certain she’ll learn a good bit about the man her grandmother married during the Great Depression. I’ve written before about how these writing projects I’ve undertaken over the last four years have led my life in unexpected directions. I’ve made significant new connections with people whose lives somehow intersected with members of my family. It has been genuinely remarkable. And I’m more and more grateful every day.  I’m going to meet George Carter’s great-nephew. Even if you’ve read Next Train Out, the name George Carter may not ring a bell. My calculations indicate that I called his name five times in the narrative, but I’ve learned over recent weeks that I probably should have cited his name more. George Carter is significant to Lyons’ story, and he’s significant to today’s story. In this era of reckoning—and, one hopes, some sort of reconciliation, eventually—the George Carters of the world need to be remembered. We cannot forget. And those of us whose ancestors are directly tied to these stories, we need to face the music. Now. Next month I will sit down with a descendant of the man who was lynched in front of the Bourbon County courthouse because he allegedly “assaulted” my great-grandmother. I’m not sure how to relay to you the awe I’m feeling, the anticipation, the relief, the gratitude, and, yes, the shame that shivers up my spine as I contemplate this meeting. I won’t detail the machinations that resulted in the heinous act on February 10, 1901. I will say that the single news story about the initial incident, which occurred in early December 1900, described what we today would call an attempted purse snatching. But perhaps it’s important to keep in mind that the newspaper where that article appeared, the Kentuckian Citizen, was published by Mrs. Board’s cousin. The newspaper’s offices occupied a building once owned by Mrs. Board’s father, a prominent physician. After her father’s death, Mrs. Board inherited that property. One of the competing papers in town, the Bourbon News—which carried a fulsome story of the lynching two months later—was published by the husband of Mrs. Board’s closest friend. I point that out to show how the power structure in town was stacked against Mr. Carter. Whatever transpired between him and Mrs. Board, he didn’t stand a chance. He was black. She was white, and she was connected. Two months after the incident, when the mob formed, whatever had actually happened on that cold December day was long forgotten. Rumors and innuendo and wild imagination had successfully altered the truth. For some in town, the crime now justified taking the life of a young man with a wife and two daughters under the age of two. Sound familiar? We have an opportunity to address some of this ongoing injustice now. Our country is awake. Video recordings provide unshakable truth. We must find the courage and the determination to start fixing these inequalities and addressing the resulting brutality. I am grateful that I will have the opportunity to speak to one of Mr. Carter’s descendants. I am grateful that he wants to meet with me. I have no idea what I will say. There is no recompense. I cannot change the past. But I’m eager to see what I can start doing today.  A headline from The Bourbon News, February 12, 1901 A headline from The Bourbon News, February 12, 1901 This week our dark times got darker. Over the month of May—still sheltered in place or cautiously emerging into society while simultaneously mourning the 100,000 Americans who have died from COVID-19—we have learned of three American citizens killed, needlessly, inexplicably, by police or those assuming law enforcement duties. All the victims were black. All the perpetrators were white. Will this outrage never end? The rage incited by these events has engulfed our cities. Protestors have blanketed the streets. Some agitators have destroyed property, burning and looting businesses with no association to the injustice. A response that initially felt rational now feels insane. In the midst of all this horror, another related story caught my attention. On Monday in Central Park, a 57-year-old birder asked a woman walking in the wooded Ramble area to leash her dog, as the area requires. She refused. As he calmly offers the dog treats in an effort to convince her to control her dog, she accuses him of threatening her and says she will call the police. With that, he takes out his phone and begins to record the incident. The woman, who is white, then calls 911 and tells the dispatcher, in an increasingly hysterical voice, that she is being threatened by an African American man. (CNN story) We all know of famous incidents in our nation’s history where a false accusation from a white woman cost a black man his life. But how many others, never reported or denied by those in power, stain our past? Today we’re finding that an immediately accessible recording device may be the only way for the black victim to get justice, even if it’s posthumously. In the Central Park instance, which thankfully did not go that far, the man and the woman actually have a lot in common. They’re both sophisticated New York City dwellers who take advantage of the beauty of Central Park. They’re both highly educated—he at Harvard, she at the University of Chicago. They’re both successful in their fields. They even share the same last name (although they are not related). But Amy Cooper felt that her whiteness gave her tremendous power over Christian Cooper. And she decided to use that power. If he had not recorded their interaction, she very well may have succeeded in having him arrested for a fabricated crime. And convicted. Because of his skin color. As I worked on Next Train Out, I had to wrestle with my own family’s story of a white woman’s alleged assault leading to a black man’s death. The only information I have about the incident is what was reported in the local and national newspapers, during a time when purple prose and editorializing were evidently acceptable. None of the news articles offers any details that might indicate that what happened should have been a capital crime. The only witness was an eight-year-old boy, my grandfather. In my fictional telling of the story, I chose to assign him the natural empathy and compassion of a human innocent, someone not yet indoctrinated into the mores of his community’s power brokers. Over our long and tortured history, I suppose we humans have always sought to subjugate others. To demonstrate power through domination. To cover up weakness by claiming the upper hand. At risk of repeating a tired refrain, this has to end. We must stop snuffing out the lives of others simply because we deem ourselves superior. The color of our skin does not grant us that privilege. We have to be better.  A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? Recently I wrote that I now have two books in my “catalog.” As I worked on the second book, it frequently occurred to me what strange bedfellows they are: a first-person narrative by a still innocent 19-year-old naturalist driven to document the flora and fauna inhabiting his halcyon getaway; and an almost gritty tale of a man stripped of his innocence who leaves his home behind and wanders from one commercial/industrial area to another with hardly a nod to the natural world around him. I love to spend time outdoors, and I sometimes feel ill-at-ease in the city. I am the daughter of a naturalist, a scientist who could identify any specimen he encountered during an amble through the woods. I, however, was never disciplined enough to fully develop his prodigious skills. While I can identify many native woodland trees and common birds, the names of most wildflowers, grasses, and garden plants are a mystery to me. And I truly regret that I can’t recognize bird songs. For years I was certain that that shortcoming alone disqualified me from writing a novel. Successful fiction is full of lush details of blooming flowers and the bees hovering around them. Or a prairie of grass and the animals that live there. Or a midnight sky and the constellations that awe us. In “Seeing the World Around Us,” I mused about the importance of being able to name a thing for that thing to fully enter our consciousness. Without that ability, we are blind. We look past the diversity of life all around us. We come to consider ourselves the all-important foreground spotlighted against an indistinguishable background. I still believe that my deficiency seriously weakens my ability to provide the sensory details readers need to feel a place. The plants and critters who share our space define our world, perhaps even define a part of who we are, even if we can’t always recognize them. So when I had a story I just had to share with others, and a fictional narrative seemed the only way to tell it, perhaps I was fortunate that that tale largely unfolded in cities or confining indoor spaces—steamy kitchens, tiny apartments, the birthing bedroom. I stole a few opportunities to place my characters outside in the fresh air. In retrospect, it’s clear that my characters, like their creator, look outdoors when they are seeking balm for a troubled soul, or a place for reflection. I was reminded of my inability to fulsomely describe a lush plein air scene as I read a recent article in Smithsonian magazine, sent to me by my cousin Barbara, about an acclaimed “naturalist, novelist, photographer and movie producer” whose name I had never encountered: Gene Stratton-Porter, born Geneva Grace Stratton in Wabash County, Indiana, in 1863. Perhaps I’m showing my woeful education by admitting I was not familiar with her, since both Rachel Carson and Annie Dillard cite her as a keen influence. I have not read any of her work—fiction, nonfiction, or poetry—but I can only imagine the richness of the natural scenes she portrayed. Her intimate knowledge of the Limberlost wilderness she wrote about, gained during countless days exploring on horseback and waiting quietly for the perfect photo, must make her tales of plucky young girls and strong women come alive. Stratton-Porter evidently brought to her writing both my father’s ability to document the natural world and my desire to tell a personal story. She had both the scientist’s eye and the writer’s imagination. In addition, she had the patience of a photographer, willing to devote the time needed to capture the most arresting photo, and then to indulge in the careful writing necessary to relay that vivid image, and her human response to it, in words. Amid all her talents, Stratton-Porter most relished her simple sensory responses to the world she discovered while wandering outdoors: “Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras.” I, too, am a nature-lover, not an academic or a trained naturalist. As life seems to slow for all of us, perhaps this is the time I need to devote to not only admiring but learning to name the beautiful things that catch my eye and restore my soul. The author of the Smithsonian article, Kathryn Aalto—a landscape historian and garden designer, as well as an author of several books—is herself a master at describing natural detail. Her first paragraph immerses the reader in northeastern Indiana’s Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, a small part of the vast swamplands that Stratton-Porter spent her life documenting: “Yellow sprays of prairie dock bob overhead in the September morning light. More than ten feet tall, with a central taproot reaching even deeper underground, this plant, with its elephant-ear leaves the texture of sandpaper, makes me feel tipsy and small, like Alice in Wonderland.” Stratton-Porter also recognized early the danger of mankind’s desire to tame the land for our own use. As Aalto writes:

“Twenty years before the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Stratton-Porter forewarned that rainfall would be affected by the destruction of forests and swamps. Conservationists such as John Muir had linked deforestation to erosion, but she linked it to climate change: “It was Thoreau who in writing of the destruction of the forests exclaimed, ‘Thank heaven they cannot cut down the clouds.’ Aye, but they can!...If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distill moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, they prevent vapor from rising. And if it does not rise, it cannot fall. Man can change and is changing the forces of nature. Man can cut down the clouds.” |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed