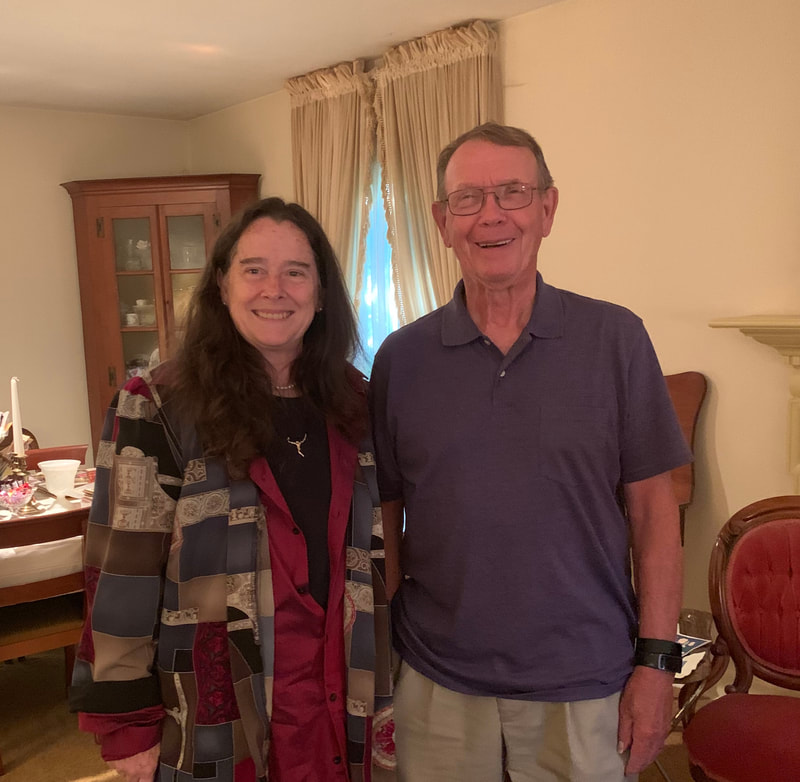

Jim and Bob McWilliams rest on the way back from Hanson’s Point in Wolfe County, Ky., November 9, 2021. Jim and Bob McWilliams rest on the way back from Hanson’s Point in Wolfe County, Ky., November 9, 2021. When I graduated from Anderson County High School in 1977, I intended to leave Lawrenceburg (Ky.) behind and never look back. I didn’t want to attend the actual graduation ceremony, but my mother made me. I refused to get a new dress (to wear under the gown?) or the required white sandals (when would I ever wear those again?). So, over and over, I clopped across the stage in that hot high school gym wearing my worn Dr. Scholl’s, the rubber long gone from the bottom of the wooden footbed, as I was unexpectedly called to accept a number of awards. My mother was mortified. She told me later that she overheard people around her whispering, “That poor little girl. Her family obviously couldn’t afford a new pair of shoes. Isn’t it wonderful that she’s receiving these scholarships?” Afterwards, backstage, I remember looking around at my classmates as they hugged and cried and laughed. I felt nothing. No one approached me and I didn’t see anyone I wanted to say goodbye to. It all seemed completely hollow. I just wanted to get home and get on with my life. Eventually, I did go back, of course, but it took me nearly 40 years. When David Hoefer and I started compiling The Last Resort, I spent a lot of time around Anderson County imagining the area in the 1940s, visiting my dad’s old camp on Salt River, and talking to the few people who still remembered him. I brought a different perspective this time, and a purpose. I was interested—fascinated, as it turned out—by my family’s long history in the area, which I had long ignored. And then this winter, by another stroke of sublime serendipity—or perhaps cosmic payback—I’ve found myself thrown together with a motley group of boys who also graduated from Anderson County High School in the 1970s. I suppose it started with our pilgrimage to Panther Rock in November 2020. My cousin Jim McWilliams had been told I knew the owner of the property and could get us access. When Jim contacted me, he mentioned that he and his friend (and my former classmate) Jeff Lee wanted to revisit a site they had hiked many times as youngsters. The three of us soon realized we were always up for a walk in the woods. When Jim and Jeff began to hike the Red River Gorge area with friends Greg Hood and Walter Moffett this past fall, I somehow wheedled an invitation to tag along. Others have joined us at times: my cousin Bob McWilliams; another classmate, Bob Cox; another of Jim’s classmates whom I knew from band, Kelly Rose; Barry Puhr, son of one of my mother’s good friends. All Anderson County graduates. All fellas I either knew or knew about when I was in school. All with completely different life histories and distinct talents. All now joined together, decades later, by our love of being in the woods. At the end of my high school years, I looked around and thought I had nothing in common with the people surrounding me. I had no idea how to talk to them. I had never felt that I fit in. And now, 45 years later, I eagerly look forward to spending time with this gang of intrepid trekkers. Our careers are behind us. We’ve set aside our professional personas and the roles we played for decades to meet society’s demands. Now we’re just a group of comrades who can’t wait to get back on the trail.

9 Comments

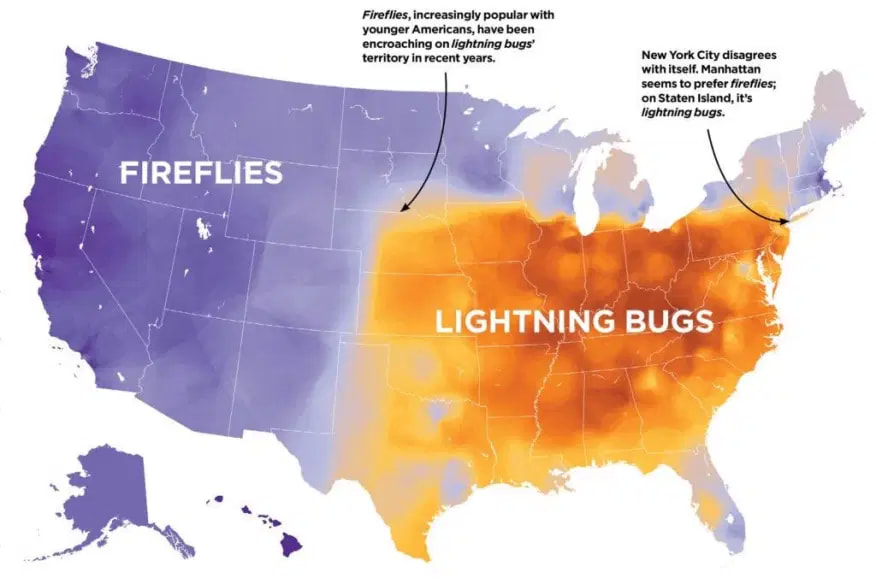

The creature in question. (Well, one of many: there are actually thousands of firefly species. Or lightning-bug species. Or whatever.) The creature in question. (Well, one of many: there are actually thousands of firefly species. Or lightning-bug species. Or whatever.) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, explores our relationship with a beloved emblem of summer. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. They dot warm summer nights like phosphorescent punctuation marks. They carry bioluminescent chemicals in their abdomens that produce a cold light, more like LEDs than Edison incandescents, to attract potential mates. Little children (and adults behaving like little children) enjoy chasing after them, catching them in hand and watching them glow on release. (I’ve been known to do this after a couple of beers.) What am I talking about? Lightning bugs, of course. Or fireflies. Or glow worms. Well, which is it? It turns out that it’s all three, though the first two names are now more common than the third. But it also turns out that what you call these creatures is, in part, dependent on the section of the country from which you hail. The following map recently appeared in an article on the Rochesterfirst.com Web site: This makes sense to me. I’ve called these beetles both names at different times but lean toward lightning bug. No surprise there, as Kentucky is smack dab at the center of lightning-bug territory. But I grew up in North Syracuse, New York, at the northern edge of the same region, and called them lightning bugs up there, too.

The article goes on to note an interesting coincidence. Firefly is more common in parts of the country that record more wildfires. Lightning bug is more typical of areas with higher frequency lightning strikes. The author correctly states that this is not proof of causation. But it is definitely intriguing. We get no help from John Goodlett on this topic. The bugs are never mentioned in The Last Resort. (Pud always was a plant guy, first and foremost.) What to call an insect may seem like a purely academic question, of little import to anyone other than linguists or entomologists. That notion would be mistaken, however. Sectional differences are an integral part of American history, with serious and sometimes dire consequences. These many differences—a true, organic form of diversity rather than the often forced and phony stuff that we’re being inundated with now—are gradually being rung out of our lives by the growing homogeneity of corporate-state culture. I like lightning bug but am okay with firefly as well. I hope distinctions like this one, and thousands of others, stick around for a while longer.  John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett with his beautiful bride, Mary Marrs Board, December 27, 1947. John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett with his beautiful bride, Mary Marrs Board, December 27, 1947. I’ve never liked Father’s Day. My father died unexpectedly when I was seven, and I’ve felt cheated ever since. I could happily wipe that holiday off my calendar. This year, however, marking Father’s Day is putting a smile on my face. Recently, my cousin Bob Goodlett had some iconic family video digitized to share with relatives near and far. Today, I’m sharing my Father’s Day joy with you. It turns out that my Uncle Leonard Fallis, husband of my dad’s older sister, Virginia, had an 8mm movie camera as early as the 1940s. I don’t recall ever having seen the following clip before Bob shared it with us last month. But there’s my father, before the war and all the horror he witnessed, strutting around his family’s property in Lawrenceburg, Ky., in his University of Kentucky ROTC uniform, being silly, mugging for the camera, while his faithful dog, Mike, gambols at his feet. The youngster at the beginning of the clip is my dad’s nephew Robert Dudley “Sandy” Goodlett, who died April 26, 2021. Readers of The Last Resort may remember references to “Sweetpea” visiting the boys’ camp. At the end of the clip, you’ll see my dad’s nephew Davy Fallis, aka “Sluggo,” who died March 7, 2018. One of the letters that Pud wrote to Davy and his parents while at basic training in Texas is included in Appendix A of The Last Resort. During a Goodlett family reunion in 1984, I remember being emotionally walloped when one of the Fallises played some of their archival movie footage that, at the time, I had no idea existed. By that summer, my dad had been gone 17 years. Suddenly, on a small screen in a northern Kentucky hotel gathering space, there he was in an intimate, playful moment with my mother, shortly before they were married. I gasped, and then I sobbed. If they played more old footage of either of my parents that evening, I missed it. (That’s Davy Fallis again, chaperoning the scene.) In the following clip, that footage is preceded by images shot on their wedding day, December 27, 1947. Lawrenceburg natives may recognize several in the wedding party: Lin Morgan Mountjoy, Bobby Cole, George McWilliams Sr., George McWilliams Jr., Vincent Goodlett, Ann McWilliams, Mary Jane Ripy, Ann Dowling, and Madison Bowmer (of Louisville). In this era of cell phones and selfies and images and video shared instantly with the world, it may be hard to imagine what it means to me to have this rare video of my dad. I have only a few memories of him from my childhood. So seeing him move—his mannerisms and his interactions with others—makes him real. It confirms what others have told me in recent years about his sense of humor and how much fun he was to be around. And, of course, it confirms all that I missed by losing him at such a young age. I am deeply grateful to Vince Fallis for preserving the original 8mm reels for more than 70 years and to Bob for making the video more widely available. This Father’s Day, I am thinking about playful Pud, and I am having a good day. The only other video of Pud that I’m aware of was shared with me by Bob Cole, Bobby Cole’s son. Appropriately, my dad is fishing. You can watch it here.

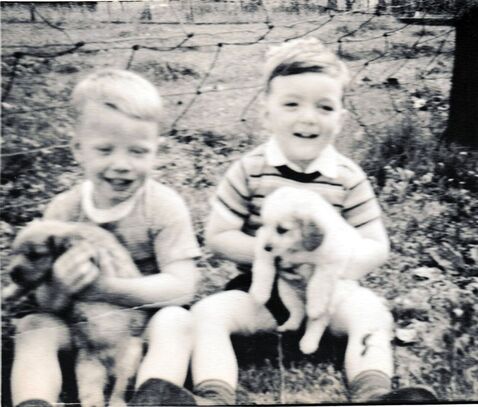

Sweetpea and Sluggo (Sandy Goodlett and Davy Fallis). Sweetpea and Sluggo (Sandy Goodlett and Davy Fallis). Only two children appear in The Last Resort, my dad’s 1943 Salt River journal: Sweetpea and Sluggo. The affectionate nicknames Pud had for his first two nephews tell you everything. In March 2018, I memorialized Sluggo, aka Dave Fallis, the elder son of my dad’s sister Virginia Fallis, when he died after a long illness. Today, I honor Sweetpea, aka Robert Dudley “Sandy” Goodlett, the first son of my dad’s brother Billy Goodlett, who died unexpectedly Monday after a brief illness. When David Hoefer, the co-editor of The Last Resort, suggested that we annotate many of the personal and historical references in the journal to provide a more fulsome picture of Pud’s world, I knew we had some work to do. David researched most of the historical and technical details. I started digging up information about Pud’s family circumstances and his Lawrenceburg friends. The first person I called was Sandy. He was the Goodlett family historian, and he had sustained ties to Lawrenceburg longer than the rest of us. David and I met with Sandy in his office in the building I still think of as the old post office, and we peppered him with questions. He was able to answer most of them, and I think he reveled in being a critical informant for our project. Soon I realized I wanted to make a trip to the Atlanta area to talk to a couple of the “boys” who used to join my dad at his Salt River camp: my cousin John Allen Moore and Lawrenceburg native Bill “Rinky” Routt. Sandy said, “Let’s go.” We picked a date and Sandy drove me and our cousin Bob Goodlett to Atlanta and back. During that trip, we were also fortunate to spend some time with John Allen’s younger brother, Joe Moore, and with Lawrenceburg natives Eugene Waterfill and Mary Dowling Byrne. It was a magical trip. And Sandy made it happen. Today, of all my dad's family and friends we visited, only Joe Moore survives. Sandy was always unselfish with his time and his wisdom. If I planned a family gathering, I knew he’d be there. In his van, we discovered we could talk for eight straight hours and still learn something new. When Sandy died, I lost not only a beloved cousin and my go-to guy for all Goodlett family questions. I lost one more connection to the father I never really knew. I’ve laughed this week with some family about Sandy’s rare equanimity and quietude in times of crisis and distress. That is not a typical Goodlett trait. Most of us are hard-headed and opinionated and high-tempered. We are intense and hard driving. Sandy kept his intelligence and his passion quietly under wraps. And when he offered us a glimpse, it was usually accompanied by that inimitable grin. If we want to honor Sandy, we should all strive to approach life’s vicissitudes with his calmness and acceptance. We should strive to be as kind and caring as he was. And we should strive to love our family half as much as he did. Read Sandy's obituary.

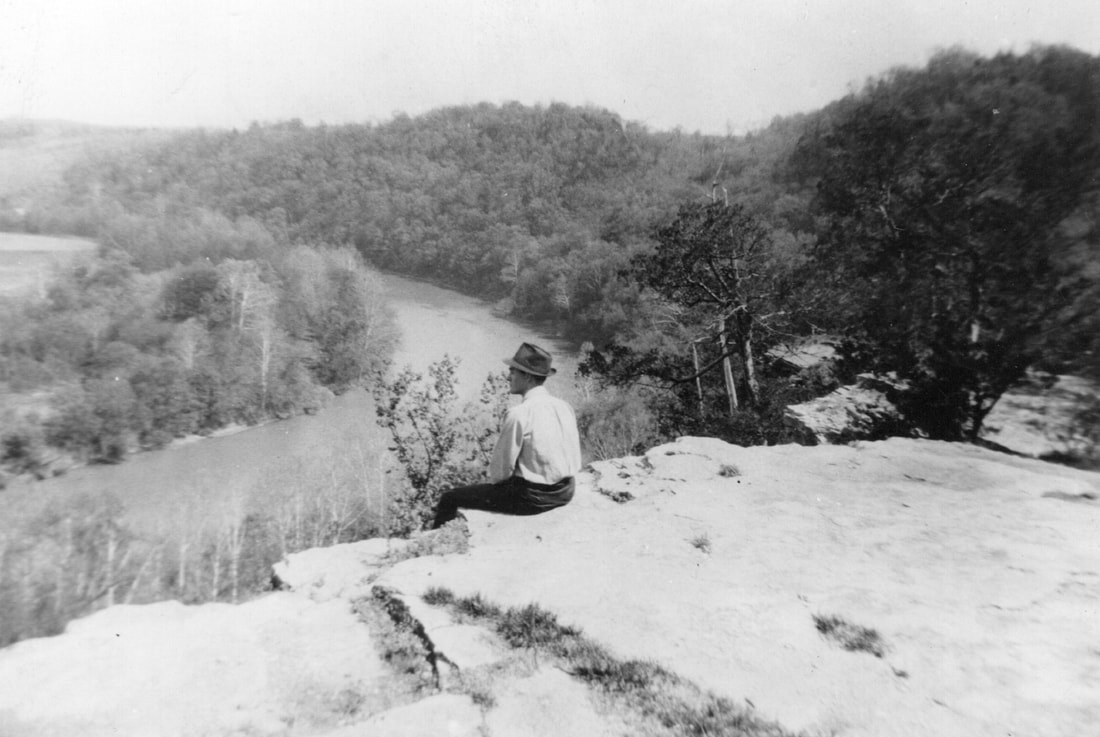

Panther Rock near Lawrenceburg, Ky. Photos by Rick Showalter. Panther Rock near Lawrenceburg, Ky. Photos by Rick Showalter. A few years ago, as I was piecing together my father’s youth from his writings and photos, it seemed clear that three of his favorite Anderson County haunts were the camp he built with Bobby Cole on Salt River, Lovers Leap, and Panther Rock. Perhaps the latter two were preserved in words or pictures largely because they were notable local landmarks, scenic hideaways from what passed for civilization in the small town of Lawrenceburg. The fact that all three feature rocky outcrops overlooking moving water may reveal my father’s affinity for those natural features. Or perhaps it’s simply a testament to the magnetic beauty of the limestone palisades that dot the eastern Anderson County landscape. In 2015, retired biologist and Lawrenceburg native Bill Bryant took me to Camp Last Resort for the first time. My own love for the woods and water made me wonder, somewhat peevishly, why no one had ever thought before that I might like to see the place that was so special for my dad. The photo on the cover of The Last Resort shows my father perched on a bluff above the small waterfall near his camp on Salt River. When I saw that photo, it seemed clear where I got my penchant for sitting with my feet dangling over a rocky cliff. (See photos below.) I still have not been to Lovers Leap, the Kentucky River overlook near where I used to bike as a teenager, on rural roads I imagine my father also pedaled. But last weekend I finally made it to Panther Rock—unfortunately, too late for Dr. Bryant, the expert on Panther Rock, to accompany me. I’m not sure what I expected. I had seen one photo of my dad seated below the rock face, but it had been hard to make out the full magnitude of what the picture relayed. When our small hiking party caught our first glimpse of the rock from the narrow approach path, however, I was dumbstruck by its immensity. We scrambled down the steep path and poked our noses into the cave at the bottom of the wall. We negotiated the fallen rocks and boulders until we reached the small stream dropping sharply away from Panther Rock. The whole area felt mystical, magical, remote. I could not believe this gem lay hidden, at least for me—majestic and unexplored—as I grew up roaming the domesticated woods and creek behind my Lawrenceburg subdivision, just a short distance away. In local mythology, Panther Rock got its name in 1773 when Elijah Scearce, a hunter and trapper from nearby Fort Harrod, was captured by a Native American chief. That first night a panther supposedly sneaked into their camp under the rock face and killed Scearce’s captor. Scearce then memorialized the area by naming it after the animal that had purportedly saved his life. The area seems to have preserved its magic ever since. I am grateful to the property owners who permitted us to absorb its wonder for a short time on a bewitchingly perfect fall day. I can only hope that generations of future explorers who stumble into this sacred place will experience the same awe as their forebears. I know I could almost hear Pud and Bobby speaking in hushed tones as they pulled bacon sandwiches from their knapsack.  Bobby Cole at Lovers Leap in 1941. Photo taken by Pud Goodlett. On May 13, 1942, Goodlett wrote in his journal, "Rinky, Bobby, and I went to Lover’s Leap this afternoon. We saw the unusual red sticky flower, and lots of pinks, but outside of these, the day was very dull. Lover’s Leap seems to have lost its attraction." More photos of Panther rock, november 2020 Birding might surprise you. A Red-Winged Blackbird in flight near Camp Last Resort, 2015. (Photo by Rick Showalter) Birding might surprise you. A Red-Winged Blackbird in flight near Camp Last Resort, 2015. (Photo by Rick Showalter) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, offers an antidote for our trying times. The last several months have brought us the unsatisfying spectacle of a nation of 325 million people devising on-the-fly strategies to outwit a virus. Yes, there is a novel pathogen on the loose and, yes, certain groups, mostly the elderly and other persons with compromised immune systems, do appear to have a heightened risk of serious infection. What remains less clear is the actual extent of the threat to other segments of the population. The public-health response has evolved over time—remember gloves sí, masks no?—but one persistent feature has been the need to close up the populace indoors, away from others of our kind. This has proven problematic because modern humans—Homo sapiens—are profoundly social creatures. Efforts at selling “virtual communities” as replacements for flesh-and-blood gatherings are almost laughably off the mark. In reality, the antisocial practices of “social distancing” play to the worst aspects of American culture: the tendency to produce isolated individuals amusing themselves with trivial pursuits while failing at healthy, long-term relationships with family, friends, lovers, and neighbors. The longer we drag this out, the more likely unintended (and negative) consequences become. Be like PudOne sensible alternative to exile-at-home is the Great Outdoors. It’s becoming increasingly clear that fresh air and sunshine have been underutilized in our often-panicky response to COVID-19. Hiking, biking, picnicking, boating, fishing, and hunting are all good reasons for going outside, where the Earth’s ultimate limits remain hugely liberating, when compared to the four snug walls of our houses and apartments.

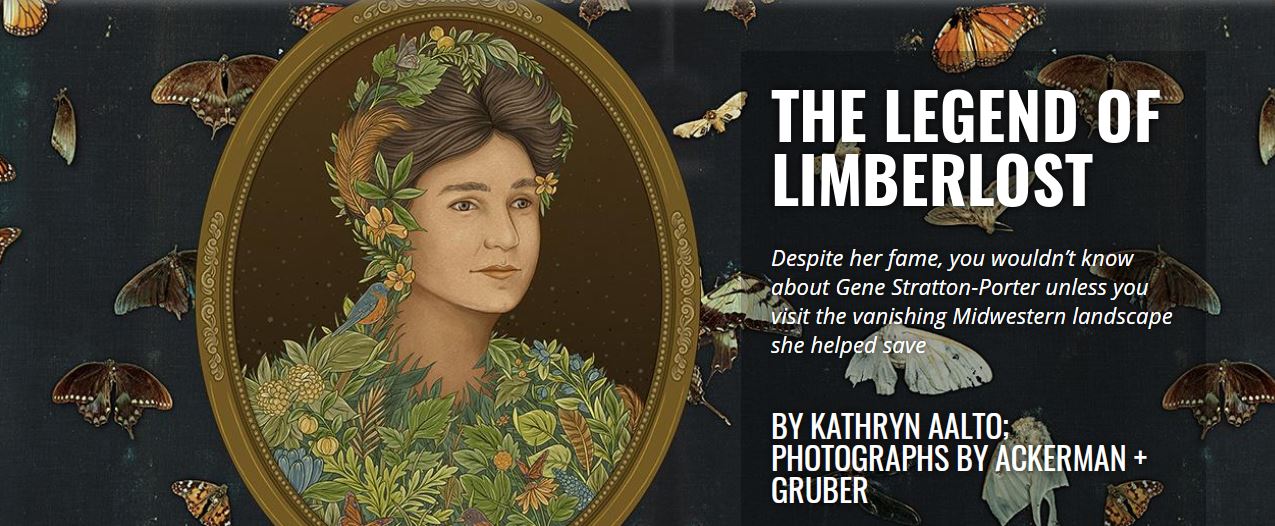

We used to understand that outdoor activities were beneficial for us. That was certainly the case for Pud Goodlett and the gang in The Last Resort. They went to the trouble of constructing a home-away-from-home, as a means of ready access to the varied and gracious Salt River environment of Anderson County, Kentucky. The cabin itself luxuriated in nature, with spiders, birds, weather, and even lightning intruding on occasion. This was no place to hide from the external world, calculating defenses against every potential risk to comfort and safety. Though Pud was a budding botanist, his journals make evident a sustained interest in the taxonomic class of Aves—our fine-feathered friends of the sky. Taken seriously, birding is an outdoor diversion of the very best sort, appealing about equally to the beauty-seeking soul and truth-hungry mind of anyone who engages in it. A great resource for beginning birders learning the ropes or lapsed veterans knocking off the rust is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Corny Orny, as I call it, offers online classes, extensive databases, and cutting-edge digital apps that can greatly enrich your birding experience. So be like Pud and light out for the world, even if it’s only your backyard or the local park. Our economy isn’t the only thing that’s been hurt by the corona shutdown. It’s time for us to get back to the business of being human.  A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? Recently I wrote that I now have two books in my “catalog.” As I worked on the second book, it frequently occurred to me what strange bedfellows they are: a first-person narrative by a still innocent 19-year-old naturalist driven to document the flora and fauna inhabiting his halcyon getaway; and an almost gritty tale of a man stripped of his innocence who leaves his home behind and wanders from one commercial/industrial area to another with hardly a nod to the natural world around him. I love to spend time outdoors, and I sometimes feel ill-at-ease in the city. I am the daughter of a naturalist, a scientist who could identify any specimen he encountered during an amble through the woods. I, however, was never disciplined enough to fully develop his prodigious skills. While I can identify many native woodland trees and common birds, the names of most wildflowers, grasses, and garden plants are a mystery to me. And I truly regret that I can’t recognize bird songs. For years I was certain that that shortcoming alone disqualified me from writing a novel. Successful fiction is full of lush details of blooming flowers and the bees hovering around them. Or a prairie of grass and the animals that live there. Or a midnight sky and the constellations that awe us. In “Seeing the World Around Us,” I mused about the importance of being able to name a thing for that thing to fully enter our consciousness. Without that ability, we are blind. We look past the diversity of life all around us. We come to consider ourselves the all-important foreground spotlighted against an indistinguishable background. I still believe that my deficiency seriously weakens my ability to provide the sensory details readers need to feel a place. The plants and critters who share our space define our world, perhaps even define a part of who we are, even if we can’t always recognize them. So when I had a story I just had to share with others, and a fictional narrative seemed the only way to tell it, perhaps I was fortunate that that tale largely unfolded in cities or confining indoor spaces—steamy kitchens, tiny apartments, the birthing bedroom. I stole a few opportunities to place my characters outside in the fresh air. In retrospect, it’s clear that my characters, like their creator, look outdoors when they are seeking balm for a troubled soul, or a place for reflection. I was reminded of my inability to fulsomely describe a lush plein air scene as I read a recent article in Smithsonian magazine, sent to me by my cousin Barbara, about an acclaimed “naturalist, novelist, photographer and movie producer” whose name I had never encountered: Gene Stratton-Porter, born Geneva Grace Stratton in Wabash County, Indiana, in 1863. Perhaps I’m showing my woeful education by admitting I was not familiar with her, since both Rachel Carson and Annie Dillard cite her as a keen influence. I have not read any of her work—fiction, nonfiction, or poetry—but I can only imagine the richness of the natural scenes she portrayed. Her intimate knowledge of the Limberlost wilderness she wrote about, gained during countless days exploring on horseback and waiting quietly for the perfect photo, must make her tales of plucky young girls and strong women come alive. Stratton-Porter evidently brought to her writing both my father’s ability to document the natural world and my desire to tell a personal story. She had both the scientist’s eye and the writer’s imagination. In addition, she had the patience of a photographer, willing to devote the time needed to capture the most arresting photo, and then to indulge in the careful writing necessary to relay that vivid image, and her human response to it, in words. Amid all her talents, Stratton-Porter most relished her simple sensory responses to the world she discovered while wandering outdoors: “Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras.” I, too, am a nature-lover, not an academic or a trained naturalist. As life seems to slow for all of us, perhaps this is the time I need to devote to not only admiring but learning to name the beautiful things that catch my eye and restore my soul. The author of the Smithsonian article, Kathryn Aalto—a landscape historian and garden designer, as well as an author of several books—is herself a master at describing natural detail. Her first paragraph immerses the reader in northeastern Indiana’s Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, a small part of the vast swamplands that Stratton-Porter spent her life documenting: “Yellow sprays of prairie dock bob overhead in the September morning light. More than ten feet tall, with a central taproot reaching even deeper underground, this plant, with its elephant-ear leaves the texture of sandpaper, makes me feel tipsy and small, like Alice in Wonderland.” Stratton-Porter also recognized early the danger of mankind’s desire to tame the land for our own use. As Aalto writes:

“Twenty years before the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Stratton-Porter forewarned that rainfall would be affected by the destruction of forests and swamps. Conservationists such as John Muir had linked deforestation to erosion, but she linked it to climate change: “It was Thoreau who in writing of the destruction of the forests exclaimed, ‘Thank heaven they cannot cut down the clouds.’ Aye, but they can!...If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distill moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, they prevent vapor from rising. And if it does not rise, it cannot fall. Man can change and is changing the forces of nature. Man can cut down the clouds.”  Salt River near Shepherdsville, Ky. Photo credit: https://www.facebook.com/awesomelazyriver/ Salt River near Shepherdsville, Ky. Photo credit: https://www.facebook.com/awesomelazyriver/ David Hoefer, co-editor of The Last Resort, shares a contemporary view of Kentucky’s Salt River. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Recently, while driving south on I-65 from my home in Louisville, I reached the point where Salt River passes underneath the interstate near Shepherdsville. From here the river flows west toward its confluence with the Ohio River at West Point. What I saw that day was very similar to what appears in the accompanying photo. The river bloomed with colorful innertubes whose passengers were basking in the glow of sunshine and (who knows) maybe an occasional adult beverage or two. I had a good laugh, because I’ve trained myself to think of Salt River as Pud’s private Arcadian getaway. But other people have other ideas about possible uses for this natural resource. Awesome Lazy River evidently sponsors these Salt River floats most summer weekends, creating a motley human carnival on the river. It’s a far cry from the mid-century black-and-white images of intrepid fishermen in waders standing in the shallow riffles near Camp Last Resort. Indeed, the American entrepreneurial spirit is something to admire. As I continued traveling south, I pondered the paradox, remembering that even Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond was within walking distance of an already substantial civilization. It appears that we humans continue to find respite in nature, especially when the comforts of society are close at hand. In loving memory of Dr. William S. Bryant (November 9, 1943 - August 5, 2019). The Last Resort never would have been published without Bill Bryant. Shortly after his article about John C. Goodlett appeared in the Kentucky Journal of the Academy of Science in 2006, Billy—as I had always heard him called—got word to me that he would be talking about the paper at a meeting of the Anderson County Historical Society. Since I was working in Lexington at the time, I contacted Bobby Cole, my dad’s good friend and fellow architect of Camp Last Resort, and offered to take him to the meeting. When we arrived, I saw that at least one more of my dad’s Lawrenceburg High School classmates was there: W. J. Smith. It was a remarkable evening of two generations sharing stories and reminiscences. I was astonished that, more than 40 years after his death, my dad’s contributions to the scientific community had prompted both Bill’s article and this hometown gathering. They’re all gone now—Bobby, W. J., George Jr., Lin Morgan, Rinky, John Allen, Jody—and now Bill Bryant is gone, too. Before the article was published, I had had no idea that Bill was working on it, no idea that he had been talking to my dad’s old colleagues (Reds Wolman, Alan Strahler, and Sherry Olson, for example). I now understand that Bill had discovered the very correspondence between my father and his Harvard Forest mentor, Hugh Raup, that I reviewed in detail just last month. In short, I had no idea that there was still any interest in my father or his work. But what I learned was that Bill knew more about my father than I did.  American Bellflower near the remains of the chimney at my dad's camp on Salt River. American Bellflower near the remains of the chimney at my dad's camp on Salt River. Twice he led me out to my dad’s old camp on Salt River. I had never been there before. It had evidently never occurred to anyone else in those 40 years that I might like to see the place that was so special—almost sacred—to my father. A few years later, as I worked on the book, Bill patiently reviewed various sections for accuracy. He encouraged me. He believed what I was doing had value. He also nudged me to include more about my mother in the book. I remember Bill visiting our home in the 1970s, talking with my mother, going over materials related to my dad’s work. I didn’t fully understand then what his interest was. But he was obviously taken with my mother’s intelligence, her courage, and her struggles to raise two daughters alone. In the end, though, I couldn’t figure out how to incorporate more of her story into The Last Resort. I promised Bill I had another project dedicated to her. It pains me that he’ll never get to read the novel I wrote about her father. Bill loved reading fiction and he loved history. I think he would have been interested in my telling of this Kentucky tale. I feel, in a way, that I’ve lost another family member—yet one more of the few remaining connections to my father. Just as I wrote recently that I wish I could have walked the woods with Pud and gleaned a thing or two from all that he knew about its inhabitants, so I wish I could have walked the woods one more time with Bill.  A very young Pud Goodlett protectively embraces his cousin Jane Moore, circa 1926. Photo from the collection of Jane Moore McKinney. A very young Pud Goodlett protectively embraces his cousin Jane Moore, circa 1926. Photo from the collection of Jane Moore McKinney. “I can’t believe those two boys built that cabin all by themselves.” And with those words I discovered one more among us who still remembers Camp Last Resort along Salt River. On Saturday I had the privilege of chatting at length with another of my dad’s first cousins: Jane Moore McKinney, the older sister of John Allen Moore to whom I dedicated the book. At age 96, her smile lights up the room and she demonstrates the same knack for storytelling as her two brothers. Her memories are clear and precise and she is a delightful conversationalist, even though challenged by encroaching deafness. Her grammar is impeccable, reflecting the education she received as a young girl at an Atlanta academy associated with Emory University (her father worked for the railroad at the time). For example, my editor’s ear perked up when I heard her say, “He was seven years older than I…”  Photos from our visit all courtesy of Bob Goodlett. Photos from our visit all courtesy of Bob Goodlett. She talked of our Aunt Sallie hauling heavy containers of milk from Grandpa Moore’s milking barn to the road to be picked up by a truck from the cheese factory in Lawrenceburg. She described how her future husband, stationed at a Navy facility outside Atlanta during World War II, leaned out of a passing streetcar madly calling her name as she stood along Peachtree Street. (She had met him once before. Click here to listen to her relay that scene.) She described life in 1940s boarding houses and sharing a bathroom with four other couples. I learned that before her marriage she had dated my mother’s cousin—and my father’s friend and classmate—George McWilliams, whom she spoke of repeatedly and fondly. When I talked to her on the phone about a month earlier, using a TTY device, she assured me drolly, “I inherited the deafness: It wasn’t something stupid I did.” She wanted to be sure we knew she had been driving and attending her weekly supper parties just a couple of years ago. Spending time with her this weekend, I have no doubt she charmed everyone at those gatherings. Now, frustrated by having to rely on a wheelchair, she seems bewildered that her body has begun to bow to age. I had met Jane briefly at a couple of family funerals. I knew she was fond of my dad. But, inexplicably, I had never made the short trip to Owensboro to get to know her or her children. So the traveling trio of Goodletts—my cousins Sandy and Bob and I—arranged a brief visit with Jane, her daughter Jane Allen, and her son Jim. This is the legacy of publishing The Last Resort. By delving a bit into my father’s story, I have been inspired to spend time with family I hardly knew. I am getting to know John Allen’s family and Jane’s family, and I have visited their brother Joe and his wife, Jean, who rescued me when I was a lost high school student in Atlanta years ago. I have spent hours talking to two of my first cousins as we traveled across the South—two cousins who had launched their careers by the time I was a child settling back in Kentucky after my father’s death. I look for reasons to get in touch with my McWilliams cousins, my Hanks cousins, and my Birdwhistell cousins. And I am delighted by all my interactions with them. Unexpectedly, I am finding family and family connections endlessly fascinating. I wish I had had the impetus long ago to reach out to them. As one of the youngest of my generation, I think I was mildly intimidated by all my interesting older cousins. But I’m glad I rounded up the courage to push myself into their lives in some small way. And I am deeply grateful for the opportunities to get to know them.  Jane's daughter, Jane Allen McKinney, is a nationally recognized artist. Her immense sculpture, towering over the Tennessee State University Olympic Plaza, is constructed of metals representing the actual percentage of gold, silver, and bronze medals the university's athletes have been awarded. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed