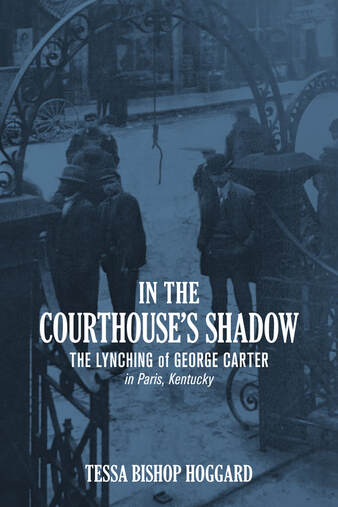

Tessa Bishop Hoggard has written a compelling book about the people and events surrounding one of the more than 350 extrajudicial lynchings in Kentucky. Tessa Bishop Hoggard has written a compelling book about the people and events surrounding one of the more than 350 extrajudicial lynchings in Kentucky. On May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer in his mid-40s, evidently decided that 46-year-old George Floyd’s alleged infraction of passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill should cost him his life. Three other officers watched as Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds—even longer than we had originally understood. Despite exhortations from the other officers and the citizens standing nearby, despite Floyd’s pleas to let him breathe and his invocation of his recently deceased mother, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck until he was no longer breathing. And then he kept his knee on his neck for another three and a half minutes. Chauvin’s defense attorneys have posed a number of counterarguments during the initial days of the trial, including that Floyd had illicit drugs in his system, that he had a heart condition that contributed to his death, and that his physical size made him a threat to the officers even after he was handcuffed and lying face down on the ground. Over the past 10 months we have learned a bit more about George Floyd and his family. We know he was a college athlete who struggled to stay in school and struggled with addiction. He spent some time in prison. We know he had moved from Houston to Minneapolis to try to turn his life around. During the trial, we saw his fiancée describe his kindness when he had first approached her at the Salvation Army where he was working security. For months we have witnessed the courage and the oratory and the passion of Floyd’s siblings and his cousins. We’ve seen the confusion of his bright-eyed young daughter whose father is now famous. He has come to feel like someone we knew, like someone we might encounter joking around at a corner market just like Cup Foods. That’s what Tessa Bishop Hoggard has accomplished in her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow. Through diligent research, she has fleshed out the story of one heretofore anonymous young Black man who was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901 after being accused of a minor crime. Like George Floyd, George Carter had previously run afoul of the law but was trying to settle down with his young family and build a good life. Like Floyd, Carter never had a chance to claim his innocence or plead his case. A group of white men with power in his community decided that he should pay with his life for a crime that we have no evidence ever even occurred. We also learn that others who endured a fate similar to Carter’s were described in the press the same way, whether accurate or not: “burly negroes over 200 pounds.” As in Floyd’s case, physical size—or perceived physical size—justified illegal actions. In Hoggard’s book, we learn about Carter’s family, their hopes and their dreams, and what happened to them after he was killed. We learn the fate of his two young daughters. We also learn about the family of the white woman who identified him as the man who had assaulted her, a crime that was originally reported as an attempted purse snatching. We learn about the fate of her eight-year-old son, who witnessed the assault and helped the sheriff identify Carter as the assailant. We learn that George Carter, like George Floyd, was a father, a son, a brother—a human being. He was not just a statistic of early 20th-century racial injustice. Just as George Floyd was not merely another victim of 21st-century police brutality. This is a problem our nation obviously has not solved. On March 18, during a House Judiciary Committee hearing on anti-Asian American violence and discrimination, Republican Congressman Chip Roy of Texas said, “We believe in justice. There are old sayings in Texas about find all the rope in Texas and get a tall oak tree. We take justice very seriously. And we ought to do that. Round up the bad guys. That's what we believe." Afterwards Roy refused to apologize for his choice of words and doubled down on the language. As columnist Charles Blow recently wrote in the New York Times: “It is hard not to draw the through-line from a noose on the neck to a knee on the neck. And it is also hard not to recall that few people were ever punished for lynchings. Motionless Black bodies have been the tableau upon which the American story has unfolded…” Those who witnessed George Floyd’s murder have testified about their sense of helplessness at the time and the enormous guilt they still carry. Some videotaped the crime and shared it with the world in horror. Those who discovered George Carter’s body hanging in front of the courthouse on that cold February morning tarried at the scene and took photos, seemingly proud of the town’s latest trophy and the message it sent. Is that a sign of some progress in the last 120 years? Are we finally beginning to push back on these unforgivable acts of oppression and subjugation? What would we do if we found ourselves witnesses to such a crime? Would we simply stand by and watch, as the two doormen in New York recently chose to do as a 65-year-old Asian American woman was being assaulted on the sidewalk in front of their building? Or would we find the power to act? In 1901, George Carter was only 21 years old when he was lynched. I wonder if he, in his final moments, silently called for his mother. Murky Press is proud to offer In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky through Amazon or by contacting Murky Press directly here. We encourage you to recommend the book to others or post a brief review on Amazon to help spread the word.

4 Comments

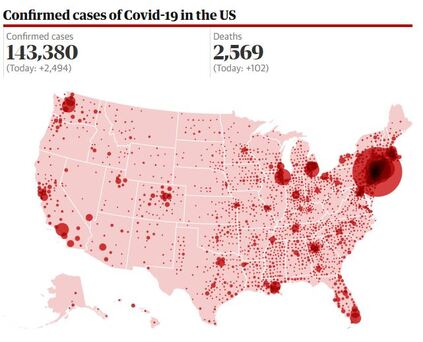

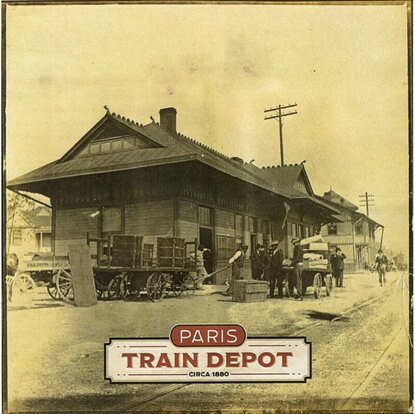

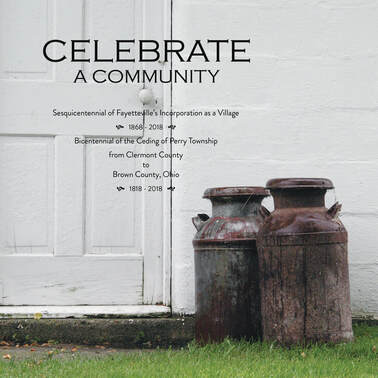

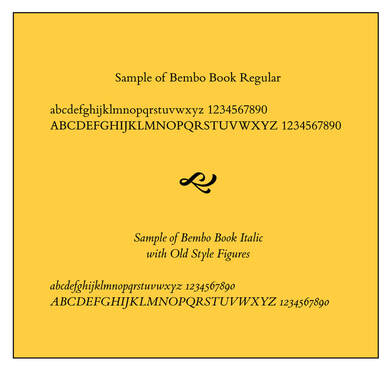

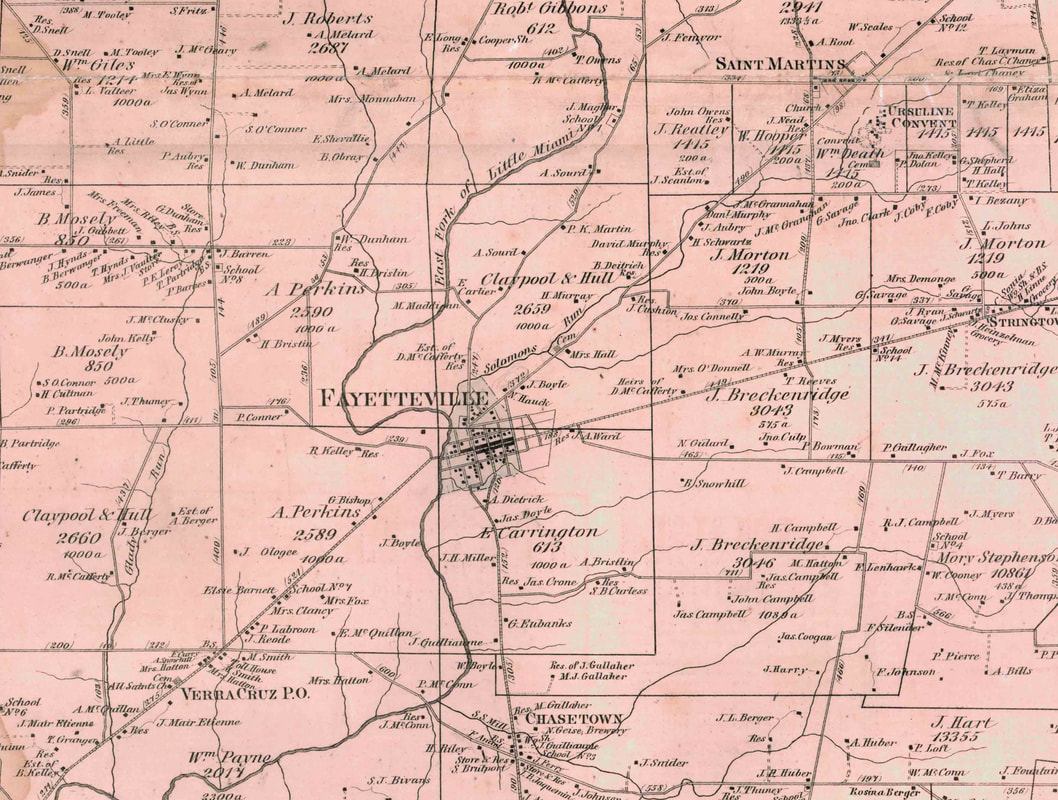

This weekend I’m celebrating a small victory. As a self-published author, I wear many hats. I am the sole proprietor of Murky Press, a small publishing business. I manage my business taxes and licensing requirements. I keep records of sales and inventory. I manage the business website and a variety of software licenses that help me do all the work. I publish through Amazon and IngramSpark, and I maintain accounts with each of those companies as well as with companies that provide my web domain and host my website and manage my ISBN numbers. I’ve written recently about my rather lackadaisical marketing efforts, but I do try to come up with creative ways to get the word out about my books. BC (before COVID) I would spend time at book fairs and speak to small community groups. I post regularly to this blog to stay in touch with all of you. And then, of course, I have to write the damn books. That may require research assistance, travel, and coordination with editors and cover designers and possibly illustrators. I do my own page layout and book design for both printed books and ebooks, so I am spared contracting with even more individuals for that work. Of all these myriad tasks, however, the one that gives me the biggest headache is troubleshooting technical problems. Now long, long ago, I worked in the tech industry and I prided myself in keeping up with technology advancements. But I’m way past that. Things change, sometimes dramatically, every three to six months now. I’m no longer interested in keeping up, and I only fall farther and farther behind with each calendar year. So I dread wrestling with technology problems. And they befall us all, whether we’re simply trying to manage a smart phone or an online business. For a couple of months now, I’ve been trying to get to the bottom of the “Not secure” message that had appeared next to the Murky Press web address in some browsers. A couple of my loyal blog readers had expressed concern about encountering dire warnings relating to stolen passwords and credit card numbers. Let me state up front that the Murky Press website was never risky to visit. I do not request passwords or credit card numbers from anyone. But I know it was unsettling to see those messages. It was for me. And I learned this summer that it could seem downright scary for some of you. Today, as you access the Clearing the Fog blog, you may finally see a closed lock symbol indicating that the site is now secure. Whew. I hope all those frightening messages have gone away. I didn’t really do anything, in the end. But after multiple phone calls and online chats, I finally got my domain provider to talk to my website host. They changed one number in my IP address and voilà—I have now been certified as the legitimate owner of this website. The cynic in me wonders if this recent security requirement—an “SSL certificate” for those of you in the know—is simply a way to justify staffing up the customer support lines and thereby expanding business. Perhaps if I were selling products from my website I would have more patience for this stuff. Nonetheless it appears I have finally solved the riddle. I finally have a website that won’t scare the bejesus out of my loyal visitors. Thanks to all of you for trusting me during these uncertain times. So raise a glass with me to one small victory over the worldwide website warlords! They stole hours and hours of my time, but you can now read future blogs with a sense of total security.  We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. It occurred to me recently that I’ve already heard from people in six states who have read Next Train Out: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Florida. I know that individuals in Georgia, Ohio, and New York have ordered the book. I have been thinking of the book as a “regional” novel, perhaps because of its settings in Kentucky, Ohio, and the Maryland coast. So I’m pleased to see its reach extend to New England, the Upper Midwest prairie, and our nation’s southernmost state. Though I confess that all of these readers have some sort of connection to Kentucky—however tenuous—I want to believe nonetheless that my limited data indicate the book has a wide appeal. That little survey of Next Train Out readers also made me realize that even during this period of social isolation we can share common experiences with far-flung friends and relatives, as well as people we’ve never met. I’ve delighted in the conversations and email exchanges I’ve had with those of you who have read the novel and have reached out to ask questions or offer critiques. We may not be able to meet for coffee or lunch, but we can still connect remotely and discuss something of interest to us both. In a much broader sense, I’m reminded that, while we’re in isolation, reading affirms our affiliation with greater humanity. Reading prods us to feel profound human connections with the characters in a book, however dissimilar we believe they are to us. While this worldwide pandemic might force us to become more self-centered in our daily routines, reading coaxes us to imagine ourselves in someone else’s situation. Faced with that character’s challenges, how would we respond? What would we do? How would we feel? In a time when the empathy of America’s citizens is once again being severely tested, it’s critically important that we look beyond our own perhaps small inconveniences and annoyances and consider the sacrifices and the heartaches of those around us. It’s impossible to turn on the television or check the news without seeing heart-wrenching stories of people who are ill, who have lost loved ones, who are tending to the medical needs of the sick without the necessary life-saving equipment, who are going to work every day to provide us with the goods and services that remain essential, who are struggling to patch together a precarious financial situation, who are wondering if the business they built will survive another month, who are fretting about their children’s education, who are struggling to stay healthy, both physically and mentally, during our voluntary home incarceration. How equipped are we, individually, to acknowledge their struggles? Do we fully recognize the need to change our habits to possibly keep someone else safe? Are we willing to make those little sacrifices? Reading widely helps train us for moments like these. It teaches us empathy. And compassion. It reminds us how small our own little world is. It reminds us that there are others with needs so much greater. In a recent article in The New Yorker, Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard, wrote: “Reading may be an infection, the mind of the writer seeping, unstoppable, into the mind of the reader. And it is also … an antidote, proven, unfailing, and exquisite.” In order, potentially, to reach an even wider audience—to spread “the contagion of reading,” as Lepore describes it—I have now released a Kindle version of Next Train Out. If you or someone you know prefers to read books on a tablet, e-reader, or other device—whether for convenience or to easily enlarge the size of the text—the Kindle version might be a good choice. It’s also an economical option for those watching their budget during these uncertain times. If you have read Next Train Out, I humbly ask you to consider writing a brief review of the book on Amazon. That may help other readers stumble across the title as they’re looking for a new diversion during our nationwide quarantine. I remain grateful for your interest.  One of the riveting photos from “Celebrate a Community.” One of the riveting photos from “Celebrate a Community.” When I established Murky Press in the summer of 2017, it was originally a means to an end: I wanted to publish The Last Resort. And since I was already working on my novel, Next Train Out, I expected Murky Press would eventually have at least two titles in its catalog. But once the business was set up, I realized Murky Press could also provide a service for others who had a project they wanted to publish. I didn’t have a clear vision of how that might work, but it seemed a logical proposition to use the infrastructure and the experience I had gleaned to help others get their books in print. I’ve been so busy with my own writing that I hadn’t yet promoted this idea beyond casual conversations with a few folks I knew had projects underway. But back in December, I was approached by the two editors of Celebrate a Community, a handsome coffee table book that uses photos, historical documents, and well-researched text to tell the history of Perry Township and Fayetteville, Ohio. I began corresponding with Peggy Mezger Cooper, one of the book’s editors and a recent contributor to "Clearing the Fog," and we gradually put together a plan to reprint the book. They had depleted the copies from their first press run and were seeking a way to meet demand for additional copies at a reasonable price. I’m pleased to announce that the book is now available to all interested parties. You can read more about it on the Murky Press home page or order a copy from Amazon.com. If you are working on a book that you think reflects Murky Press’ mission, and you are searching for a way to get it published, get in touch with us. We may be able to help you find your way.  In 2017, the Poynter family acquired the historic Paris train depot and began a careful and loving renovation of the property. It is now the Trackside Restaurant and Bourbon Bar, the site of our book launch party April 5. In 2017, the Poynter family acquired the historic Paris train depot and began a careful and loving renovation of the property. It is now the Trackside Restaurant and Bourbon Bar, the site of our book launch party April 5. I did it. Next Train Out is published. For those of you who have faithfully followed the twists and turns of my adventures writing a novel, this is supposed to be the sweet spot. The pinnacle. But I largely feel relief. And fear. What did I miss? What did I forget to do? Was I right to scale back Effie’s vernacular? Should I have expanded the story, given that there were so many more details to share? It’s time to find my way to acceptance. I am a severe taskmaster, but at some point I had to cut the cord and release this product of hard work and imagination to you. I hope it will find a few readers. I hope some of those readers will find Effie Mae and Lyons memorable. I hope the twentieth-century story will shed some light on the issues we’re still facing today. Thank you, again, for coming with me along this journey. Your words of encouragement and support are what finally got me to the finish line. If you decide to read the novel, I would be further indebted if you would consider writing a few words about your response to it on amazon.com. (Scroll to the bottom of the page to see where you can submit a review or a video.) Or send me your comments for a blog post. Either might encourage others to give it a look. Meanwhile I invite all of you to join us for the official book launch April 5 at the very train depot in Paris, Ky., where I have imagined Lyons first made the decision to turn his back on his family and his reasonably secure life. We’ll have music provided by Carla Gover—traditional Appalachian singer, songwriter, instrumentalist, and clogger—playing Effie Mae’s favorite music, and special food created by Trackside Restaurant’s chef John Wheeler to represent dishes evocative of the narrative’s historic period and geographic region. On April 14, I’ll be speaking about Lawrenceburg’s ties to the story at the monthly meeting of the Anderson County Historical Society. Everyone is welcome at both events. (Details) Many of you have asked, “What’s next?” My usual response: “Retirement!” I consider myself a “one-and-doner.” But Effie Mae’s words may better reflect what's in store for me: “It’s all part of life’s road map that I have no way of reading. I just take the turns as they come.”  The pencil holder on my office desk says it all. The pencil holder on my office desk says it all. I typically like detail work. I like precision. My eye is trained to see tiny variations in a pattern or errors that others might skip over. That doesn’t mean I don’t sometimes miss things or get things wrong. But I’m accustomed to settling down and doing careful, painstaking work. I have to confess, however, that there have been times recently when I was ready to raise my hands in surrender as I have worked through the final intensive edits of my novel. I know how critically important this phase of writing is. I usually relish the final polishing. But after three rounds, I am exhausted. Before I say more about that, however, let me first say how deeply indebted I am to the editors and readers who pored over the manuscript and alerted me to issues that, without correction, would have embarrassed me or confused readers. There is no question the book will be better because of their efforts. But back to my numbing fatigue. I have written before about how writing is an infinite series of decisions: choosing the next conflict, the next scene, the next setting, the characters’ reactions, the syntax of the next sentence, the next word, a better word, and punctuation that is both consistent with convention and imbues the rhythm and music—and meaning—that you want to convey. For someone who hates making decisions (that would be me), it can be torture. In this late stage of the novel-writing process, everything is a decision. An edited page that appears to have two simple markups takes 30 minutes to revise. Shall I take that comma out or leave it in? Grammar rules say it’s acceptable, but the short clauses make it optional. Does it change the emphasis if I remove it? Does it change the rhythm? Why did this editor suggest taking it out? Read it with the comma. Read it without the comma. Repeat. One more time. Which option relays what I’m trying to say? Will any reader ever give a damn? Is it time to walk Lucy? Chicago Manual Style or AP Style? Arabic numerals or all numbers spelled out? Spaces between the dots in an ellipsis or use of the ellipsis symbol? And the comment I now dread the most: Is this phrase too modern? Since I started putting words on the page three years ago, I’ve recognized the importance of getting the language right. The bulk of the novel is set between 1921 and 1942. I wish I had a dollar for every phrase I have looked up to see when it came into the lexicon. “Pratfall”? “Down payment”? “Hang with”? “Have my back?” Even with the convenience of the Internet, those searches take time. Once I’m satisfied that the words on the page are the best they can be, there’s the book design to consider. A few weeks ago, I told an interested party that I was starting the page layout process. It was clear that she couldn’t imagine the decisions that requires. A novel has a simple layout, so even I thought that part of the project would be relatively straightforward. But I found a way to agonize over the font size, the line spacing, the margin size, the Table of Contents. Tonight, however, I am celebrating. I am done. I’ll request one final proof. Complete one final read-through. Pray that any remaining issues are tiny and easily remediable. But, mostly, pray that I find them before my careful readers do!  The family milkhouse is pictured on the cover of this handsome book filled with historic photos and documents. The family milkhouse is pictured on the cover of this handsome book filled with historic photos and documents. Peggy Cooper, of northern Kentucky, introduces Clearing the Fog readers to Celebrate A Community, soon to be reprinted by Murky Press. More about this exciting project coming soon! The stars spread across the sky as they do only when you live on a dairy farm acres away from the nearest neighbor. The milking was finished and I walked with my father, hand in his, from the barn to the house. At the sidewalk to the milkhouse, he suddenly paused and sat on his heels, his scratchy bearded cheek against mine, one arm around me holding me close and the other pointing into the sky, guiding my gaze to the Big Dipper. It was there at the end of his finger, the Big Dipper, over the milkhouse. Who knew that there were pictures in the sky made of stars, and over our milkhouse? When I started this book project, my husband would tease me about “the Center of the Universe,” the little town I was writing about, Fayetteville, in Perry Township, Ohio. He was making fun of my attachment to this little one-stoplight crossroads. My father lived his entire life on the farm where that milkhouse stands beneath the Big Dipper. My brothers are farmers tilling the same land farmed by five generations of our family. That milkhouse is now on the cover of the book that is filled with photos and memories of the community around that milkhouse, and many of my father’s stories are within the covers of that book. Who knew that there were pictures in the sky made of stars, and over our milkhouse? Indeed, who knew that Fayetteville and Perry Township really are the Center of the Universe?  My great-grandmother Atha (Mrs. R. H.) Marrs on August 14, 1955, at the age of 91. Mrs. Marrs appears in two Lawrenceburg scenes in the novel "Next Train Out." Photo provided by Bob McWilliams. My great-grandmother Atha (Mrs. R. H.) Marrs on August 14, 1955, at the age of 91. Mrs. Marrs appears in two Lawrenceburg scenes in the novel "Next Train Out." Photo provided by Bob McWilliams. For many, writing is a solitary pursuit. I prefer a host of collaborators. The novel I’ve been working on for a number of years would never have been completed without my “support team.” It started nearly 10 years ago when my then-neighbor, Chuck Camp, while chatting on my back patio, took an immediate interest in the story of my mysterious grandfather. Within hours he had begun to discover the path my grandfather had taken after abandoning my mother and grandmother. Over the next few years he continued to unearth amazing details about Lyons’ early life and his military service. I owe the story, in all its richness, to Chuck. I had never written fiction before, and I had a lot to learn. I depended on classes and instructors at Lexington’s Carnegie Center for Literacy & Learning for teaching me the nuts and bolts of the craft. I’m still an unabashed novice, but they helped me understand what was important to readers and how you put together a story that will keep them engaged. There were numerous times over the last three years when I felt I wasn’t up to the task. I started and restarted and reimagined how to construct this story. I tried a variety of different approaches. Even when I felt I had a solid half of the book complete, my determination waned. It was just too hard. Too time consuming. I had no idea what I was doing. That’s when my intrepid readers and editors stepped in to shore up my confidence. My long-time friend and former boss, Roi-Ann Bettez, was my first beta reader. She is an enthusiastic reader of all sorts of material and an acute editor who has applied her talents to her husband’s award-winning books about the First World War as well as to nonfiction books produced by her friends. She offered honest critique of what worked for her and what didn’t. She helped me focus on what the reader needed from the characters. And she let me know what parts of the story she found satisfying. She’s still working with me, offering encouragement and insights at the very end of this process. Readers of this blog know that Tim Cooper took on the role of nearly full-time mentor and coach after retiring from teaching in 2018. A voracious reader and former writing instructor, Tim and his Minnesota buddies are competitive readers who know more about contemporary literary fiction than anyone I know. He patiently coaxed me to go where I wasn’t comfortable. I was able to lean on his academic interest in history for creative ways to keep the novel firmly rooted in its times. Tim and I have spent hours in his living room poring over chapters and paragraphs and arguing about specific words. He pushed me. He encouraged me. He wouldn’t let me quit. My cousin Bob McWilliams loaned me his family scrapbook full of photos and newspaper clippings, which were invaluable in putting together the stories of our Marrs ancestors and their McWilliams contemporaries. Rogers Bardé, my cousin through my grandfather Lyons’ family, was the original impetus for seeking information about him. Her voluminous genealogical research into that branch of my family helped me understand my Paris, Ky., roots a little better. As I approach the final publication phase of the book, I am once again relying on the talents of Barbara Grinnell, whose cover design for The Last Resort perfectly captured the book, its author, and its historic period. I’ve pulled in yet another former colleague and expert editor, Jo Greenfield, as my final proofreader. I’m delighted to have her as part of this process. And I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge Mr. Vice President of Everything, my husband, Rick. He does battle with the print store managers, hobnobs with local authors, shares his creative marketing ideas, opens his wallet wide for the next class or the next production expense, and is an incredibly helpful commenter on the novel itself whenever I can convince him to sit quietly for an hour and read. This project would not be coming to fruition without the unselfish contributions of all of these folks. I offer them my heartfelt gratitude, and I hope the final product is worthy of their efforts. I’ll be satisfied if I learn that the novel offers a little entertainment, a little illumination into our human contradictions, and a little distraction from our contemporary afflictions.  Introducing Monotype’s Bembo font, the font I have chosen for the text of my novel. Introducing Monotype’s Bembo font, the font I have chosen for the text of my novel. You already know that I love words. I love to play with their meanings and their sounds. I take pleasure in creating musical sentences that sing to readers. I want to get the rhythm and the beats just right. I also enjoy laying out the words on a page. I want to create a page that draws a reader in with an appealing typeface and plenty of white space. I understand that, in the early moments when you’re trying to hook a reader, the look of the page may be as significant as the very words themselves. In 1985, Aldus Corporation introduced PageMaker, the original desktop publishing software for Apple Macintosh computers. I started using the software shortly afterwards, and I’ve been fascinated with page layout and design ever since. I’ve read books, taken classes, and sharpened my layout skills at nearly all the jobs I’ve held, designing user’s manuals, restaurant training materials, marketing flyers, annual reports, and tourism books. Some years ago I moved on to Adobe’s InDesign, but I still enjoy the process of laying words on a page. After I decided that Murky Press would publish Next Train Out, one of the first decisions I had to make was what font I wanted to use. For The Last Resort, I chose Garamond, a classic font commonly used in books. That would have worked fine for the novel, too. However, I did a little research to see what fonts were popular in the burgeoning self-publishing business. Most I was familiar with, but one I wasn’t, and it piqued my interest. What drew me to Bembo was not necessarily its whimsical name, although that may have tugged at me just a bit. (I learned that Pietro Bembo was a 15th-century Italian poet and cleric.) What caught my eye was the font’s lightness, its simple clean lines and the beauty of some of its individual characters. It is an “old-style” font, based on Venetian designs from the Renaissance. When I learned that Monotype created its commercial version of Bembo in Britain in 1928-29—key years in the novel—I decided it was perfect for my purposes. When I saw that Penguin Books and Oxford University Press use the font, I figured I couldn’t go wrong. Acquiring Bembo for use with my page layout program required a small contribution to Monotype Corporation, but I have already reconciled that expense. After creating some sample pages, I can’t imagine using anything else.  The forlornness of an empty boat dock. Photo by Rick Showalter. The forlornness of an empty boat dock. Photo by Rick Showalter. After the longest summer in memory, we’re finally transitioning to winter. A little snow this week offered a taste of my favorite weather: bright blue skies, snow balancing on the tree limbs, and temperatures in the 20s keeping the ground hard and the mud at bay. One sign of impending colder weather at my house is the dry-docking of our metal johnboat. In our case, this simply means hauling the boat out of the water and leaving it to rest upside-down on the nearby shore. I came back from an event last Sunday afternoon and saw the boat was missing from its slip. That always makes me a little sad. Although we rarely take the boat for a spin on the lake these days—lightweight kayaks are just so much easier—its mere presence suggests the possibility of a lazy summer day fishing on the lake. It evokes nostalgia for a more tranquil time when bobbing on the water was an acceptable way to spend an afternoon. But we have found that ice tends to build up inside the boat in the winter, and harsh winds can then heave the extra weight against the aging dock and pull hard at our makeshift mooring. Removing it from the water this time of year eliminates one thing we have to worry about. When it’s missing, however, I feel the void, the absence of something significant. I’m in the middle of another transition that could also symbolize a sort of loss, if I allowed it to. But I prefer to see it as an empowerment, a taking control of a situation that could at times feel hopeless, a situation that made me grapple with my own worth and the value of the work I’ve chosen to do. This is familiar territory for every writer who wants to see work published. I’ve spent several months reaching out to literary agents and small publishing houses searching for someone who might be willing to take a chance on my novel. Like so many writers, I now have only an inbox full of rejections to show for my efforts. It’s a tedious, time-consuming process that I still find interesting, but I’ve decided it’s just not how I want to wile away my hours. I’m ready to accept defeat and retake control of my project. It takes a certain self-assuredness—or even cockiness—that I don’t normally possess to assume that my book has value even though no legitimate enterprise agrees. What’s at stake, however, is small: personal embarrassment, acknowledgment that my talent and skills are limited, shunning by those with legitimate claim to the title “writer.” I can accept that. I have no other literary aspirations. I’m ready to take the chance. So I’m getting excited about designing the book that I want to offer to willing readers. I’ll be able to title it what I want, include the front matter I want, and rely on my talented graphic designer, Barbara Grinnell, to create a cover we both love. Of course, the final editing and proofing will now fall on me, or on other professionals I enlist to help. But I think I have a course mapped out, and I’m excited to be going down this road. It’s freeing sometimes to let go of dreams that are only weighing us down. Sometimes we have to turn a corner, move in another direction, accept a transition to an imperfect state of things. I’ve written a story that I want to share with friends and family who are interested, and I have a path for accomplishing that. That’s what’s important. And that I can do. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed