A poster, by artist Vernon Grant, issued by the U.S. War Food Administration in 1944 to discourage civilian food waste. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. A poster, by artist Vernon Grant, issued by the U.S. War Food Administration in 1944 to discourage civilian food waste. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. As we recover from our holiday feasts, David Hoefer, co-editor of The Last Resort, reflects on the meals historically available to our troops in battle. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. I’ve recently been reading Theodore Roosevelt’s book The Rough Riders about his volunteer cavalry unit that fought in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. It’s very much an adulatory view of the conflict but, beneath the pro forma sentiments, there remains plenty of interest for the historically minded. One point that comes across is the sheer difficulty of making war in modern times, regardless of the goals or objectives involved. The projection of large forces over great distances calls for sophisticated logistical systems—systems that are often assumed to exist even when they don’t. Roosevelt remarks more than once about the inadequacies of transport that confronted his men both going to and fighting at the fluid Cuban battlefront. As for the food—well, let’s just say there weren’t a lot of farm-fresh homecooked spreads. Meals consisted of hardtack and sometimes rotten meat, with nary a fruit or vegetable in sight, and shortages of coffee and sugar, too. Pud Goodlett faced similar challenges as he fought with Patton’s Third Army in Europe during the closing months of World War II. Winter weather and the Wehrmacht were the primary obstacles, of course, but maintaining adequate nourishment—or simply getting fed—would have been a major concern. The U.S. Army’s answer was the K-ration, an individually packaged lightweight meal that supplied sufficient calories for soldiers in the field, at the expense of taste, variety, and other virtues of civilized eating. To experience a K-ration meal—vicariously, of course—watch the video below. The contemporary narrator seems to have a genuine appreciation for the K-ration, which he examines in considerable detail. I wonder if Pud felt the same way, as he wolfed down the biscuits and smoked the cigarettes in some anonymous foxhole always too close to an increasingly desperate enemy?

4 Comments

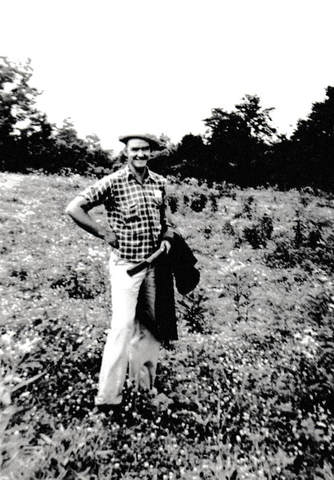

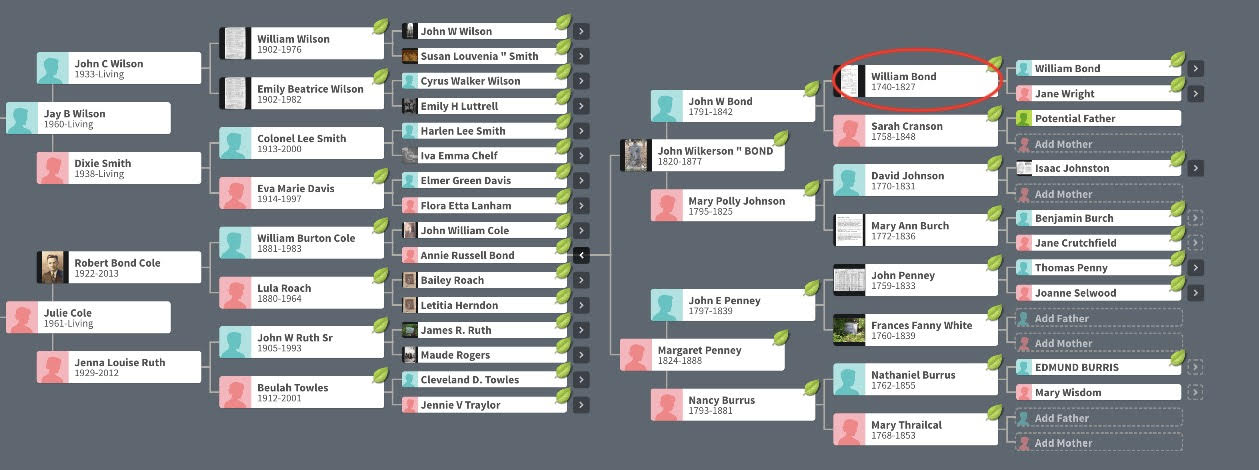

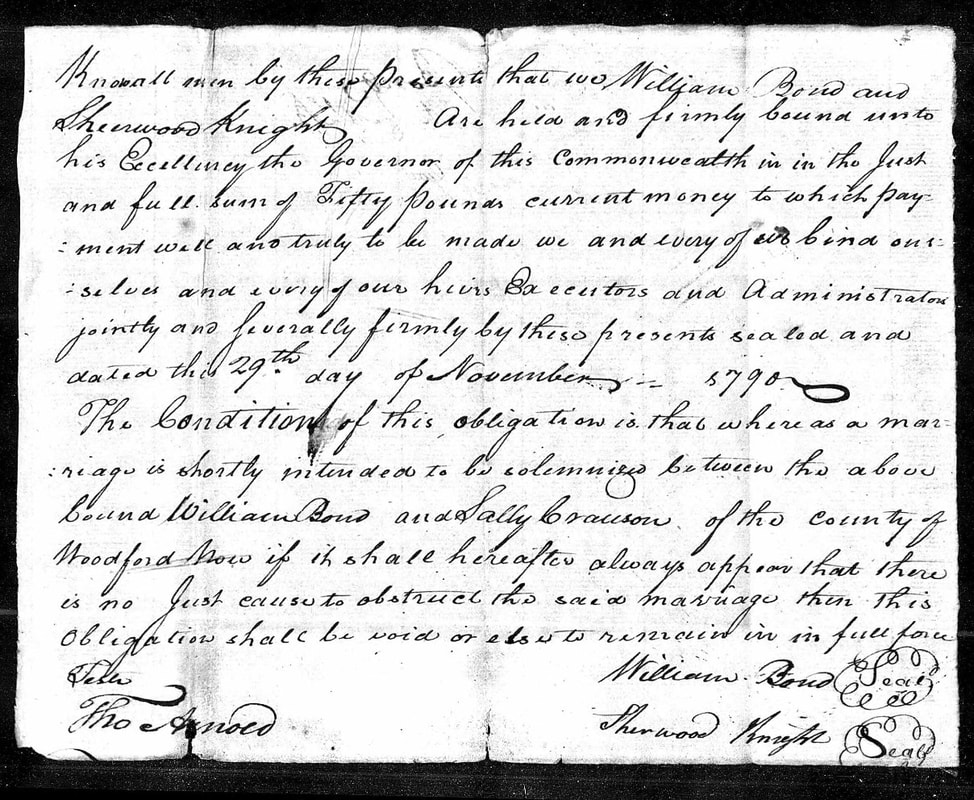

The University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center resides in the Margaret I. King Library. The University of Kentucky Special Collections Research Center resides in the Margaret I. King Library. As a child, I remember dull Sunday afternoon car trips driving through western Maryland. I now understand that my parents were looking for a connection to Kentucky in the rolling hills and farmland. Having been displaced first to Massachusetts and then to Baltimore, it was the best substitute they had for the familiar scenery they longed for. Even before that diaspora, Pud had been forced to leave central Kentucky to fulfill his military obligations. After returning home and completing his bachelor's degree at the University of Kentucky, he chose to leave again to pursue a doctorate at Harvard. It is clear, however, from the notes he kept in his second journal, dating from 1953-54, that he intended to return to his home state someday. Upon returning from a working trip to Washington D.C., on March 9, 1953, Pud finds a letter from H.P Riley, professor in the Department of Botany at UK. Pud writes: “Among the otherwise useless mail awaiting our return was a friendly, warm letter from H.P. Riley, informing me in a poker-faced way that McInteer may retire 1 June, and did I know of a possible replacement. In all modesty, the requirements for his successor fit me like a glove. I’ve been in a tizzy at prospects of returning to Ky. I finished the laborious job of composing a reply tonight and will send it tomorrow.” Later, on March 14, he continues: “[Mary Marrs] and I were in a dreamy mood about getting back to Ky. tonight. We have a tough problem in devising ways and means to get our belongings home. Probably a part-load in a moving van would be best. One thing is certain, it will be expensive.” Pud eventually interviewed for the position but, in the end, Professor B.B. McInteer decided not to retire and the opening with the UK herbarium never materialized. My parents continued to make trips home to visit family, and Pud continued to talk to Riley about a position at UK, but no further opportunities for employment in Kentucky arose. Although he could never secure a position at the University of Kentucky, his legacy will now have a place on campus. Thanks to inquiries initially made by Bobby Cole’s daughter-in-law, Teresa, The Last Resort: Journal of a Salt River Camp 1942-43 will be available at the UK library’s Special Collections Research Center. When contacted about possibly acquiring the book for this collection, Jaime Burton, director of research services and education, wrote: “We are so pleased that we are able to serve as further stewards of your father’s recorded experiences, and look forward to securing his place here on campus once again! This is a great story.” It seems the perfect resting place for his words. The center’s mission states, in part: “The Special Collections Research Center sustains the Commonwealth's memory and serves as the essential bridge between past, present and future. By preserving materials documenting the social, cultural, economic and political history of Kentucky, the SCRC provides rich opportunities for students to expand their worldview and enhance their critical thinking skills. SCRC materials are used by scholars worldwide to advance original research and pioneer creative approaches to scholarship.” The UK library already has a number of my father’s academic publications (including the most widely available, Geomorphology and Forest Ecology of a Mountain Region in the Central Appalachians), but it’s a special gift to know that a book that reveals more about his personal life and his ties to Kentucky will also have a home there. I hope Kentucky enthusiasts and researchers find it a useful volume that offers a window into a specific era in our Commonwealth’s history. Welcome home, Pud. Merry Christmas.  My favorite part of Christmas has always been the music. As a child, I looked forward to going to church and singing the Christmas hymns and traditional carols. At home, I wore out my parents’ records, which were largely sweeping, symphonic renditions of those same tunes. I believe it was my sister who first introduced me to Handel’s Messiah, and that recording immediately became part of my regular rotation on the turntable. I studied piano for 15 years. I was never very good. But it helped me learn a little about music fundamentals and the classical repertoire. Eventually I came to love the practicing. It was my opportunity—my obligation, even—to withdraw from the demands and rigors of the outside world into a place where only the music existed. It was as if my peripheral vision blurred, and I could see nothing beyond the notes on the page and the keys on the piano. Practicing required my complete concentration, as well as a coordinated physical and mental effort. When I was tuned in to whatever piece I was working on, the grievances, the annoyances, the embarrassments, the insecurities that tormented me at other times could not intrude. I have my father to thank for introducing me to music. I’m fairly certain he was the one responsible for the Christmas records, as well as the recordings of Burl Ives and Herb Alpert and Peter, Paul, and Mary (and the musical satirist Tom Lehrer) that were available to me as a child. But most importantly, he was the one who insisted that my sister and I start piano lessons at a young age. I imagine that was in part because he had not had that opportunity. Recently, Bobby Cole’s daughter, Julie, sent me a newspaper clipping that indicated that Pud’s older sister, Virginia, did study piano as a youngster. The 1923 article states that she performed a piece titled “The Dawn of Springtime” at Miss Jessie Mae Lillard’s student recital at the Lawrenceburg Christian Church. She would have been about 13 then (and my dad would have been 1). There was still a piano in the Goodlett home when my dad was a boy: I have often heard the story of how his pet raccoon tripped lightly down the piano keys one day, casually flipping the ivory off several keys with his sharp nails as he went. I also understand that was the last day he had the honor of being a pet in the Goodlett household. As an adult, my dad evidently educated himself about classical music, at least sufficiently to have a genuine appreciation for it. I remember casual family dinners at the black drop-leaf table in our pine-paneled den in Baltimore, my father listening to a classic radio station while conducting with his fork.  Pud’s nephew, Robert Goodlett II, plays with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. Pud’s nephew, Robert Goodlett II, plays with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra. My cousin Bob Goodlett, who has played contrabass with the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra for over 40 years, recently suggested that his father, Vincent—Pud’s oldest brother, also emphasized musical study with his children for similar reasons. Both brothers fiercely valued a classical education, and both battled long odds to complete their schooling. Bob reminded me that, to pay for law school, Vincent would go to school for a semester and then work for a semester. After serving in the Army for three years, my dad left his home and family again to pursue an advanced education. Years ago I stumbled across a classical high school curriculum that he had compiled at some point, perhaps for a school he one day hoped to open but, more likely, simply to show the public educators at the time how it should be done. According to Bob, Vincent managed to collect a number of classical recordings, including a set of Arturo Toscanini conducting Beethoven’s symphonies. (Bob tells me that his parents had some success getting him to sleep when he was a baby by playing Beethoven’s 2nd Symphony. As he learned to talk, he would request “Teethoven No. 2.”) Vincent also had a 1955 recording of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto featuring Jascha Heifetz. When the recording reached the cadenza, Bob distinctly remembers my father saying, “Now he gets to show off.” That must have resonated with the 10-year-old boy, who spent the next few years mastering several instruments while simultaneously pursuing baseball stardom. Bob recalled one more story of the fun my father had with music. While teaching at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Pud had a student, Sherry Olson, whose husband, Julian, played French horn with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. The orchestra was evidently preparing to perform Beethoven’s 9th, and Pud and others were taking bets, I imagine while sipping a bourbon, about whether the fourth horn would mess up the famous solo in the quiet third movement. Although as a teenager Pud struggled to appreciate Bobby’s devotion to the radio he brought to the quiet camp along Salt River, as an adult music obviously gave him much pleasure. He is not alone, of course. Listening to music—of whatever genre or style—allows us to shut out the raging noise of the world around us as well as drown out our own cacophonous thoughts. It’s also a way to share with others one of the truly sublime human endeavors. For all those reasons, I hope your holiday is full of music.  Bobby Cole on his family's farm. Bobby Cole on his family's farm. The Last Resort—the camp along Salt River and, ultimately, the book by the same name—came to pass because of the bond that formed between two classmates. Pud Goodlett and Bobby Cole shared a love of the outdoors and relished the time they spent together fishing and hunting. At some point in their teen years they hatched the plan to build the cabin on the bluff above the river on the Cole family farm. Thus began the idyllic days described in Pud’s journal. The relationship between the two boys appears deep and sometimes complicated. Pud is occasionally annoyed by Bobby’s radio, his fastidiousness, or his desire to head home for a shower and a shave after a few days at camp. But Pud is also proud of Bobby’s marksmanship and his ability to identify the trees along the river. It is clear that he is devoted to his friend, and his sadness when Bobby is called up for service is profound. On November 1, 1942, Pud writes, “Went to camp early this morning for the first time since Bobby left. All the bottom seems to have fallen out of the joy of that wonderful, free life on the river. Bobby’s worrying about the dirty floor, the big leak, the state of his radio, the fact that our floor has spread and the countless other dear old-maidish things he did are gone, seemingly forever. I don’t believe I’ll ever be able to spend a weekend here until he can again spend it with me.” Of course, Pud did return to the camp, but he had to enlist a whole group of young boys from his Scout troop to try to fill the hole created by Bobby’s absence. That never proved completely satisfactory, but it did allow Pud to extend his time at the camp until he, too, was called to fight a war. From the limited evidence we have, the boys seemed tighter than mere friends. They seemed more like brothers. In fact, we now know that they were cousins. Bobby had a keen sense of his family’s history and its roots in the area, and I imagine he was aware that the nearly 400 acres his father and older brothers tilled had been in the family for generations. John W. Cole had pieced the property together in the 1880s from extensive lands owned by his Bond, Kavanaugh, and Penney (yes, of J.C. Penney lineage) ancestors. Some had settled the area in the late 1700s. The main Kavanaugh home had been built in 1840. The stone for the chimney Bobby and Pud constructed, which still stands today, was confiscated from the crumbling foundation of a former slave cabin.  On the farm, circa 1918. Left to right: James L. Bond (1855-1934), William B. Cole (1881-1983), Lula Roach Cole (1880-1964), J. W. Cole (1905-2001), Allen Carroll Cole (child, 1916-1987), John William Cole (1860-1924), Mary Louise Cole Ransdell (girl standing, 1911-1988), Annie Bond Cole (1862-1948), John W. Bond (1846-1929), Phoebe Utterback Bond (1851-1940). Photo provided by Bob Cole. Bobby knew all this. But I doubt that Pud was aware of his own familial ties to the land. Thanks to the curiosity of Bobby’s daughter, Julie, and to the detective abilities of her son, Nicholas, we now know that Pud and Bobby share a common ancestor. William F. Bond was born in Virginia in 1740. After his first wife died sometime around 1786, he accepted a land grant awarded for his Revolutionary War service and moved his four children west with the Penney and Burrus families to what is now central Kentucky. In 1790, he married Sarah Cranson, who hailed from what was then Woodford County, Virginia. William and Sarah had five more children. Bobby was a descendent of their oldest son, John. Pud was a descendent of their second oldest daughter, Ailse. In fact, the boys can also trace their families back to a common Utterback ancestor. And Pud’s mother had connections to the Bond family through her maternal grandmother, Mary Ann Routt. Of course, we’re talking about a small rural community. It’s no surprise that two families with longtime roots in the same geographic area have common ancestors. But it somehow feels special to know that Pud and Bobby were connected by more than the teeming water of Salt River. They were connected by blood. Transcription of marriage contract (with gratitude to Nick Wilson, Bobby Cole's grandson, for offering his legal and historical expertise):

Know all men by these presents that William Bond and Sherwood Knight are held and firmly bound unto his Excellency the Governor of this Commonwealth in the first and full sum of fifty pounds current money to which payment will and truly to be made we and every of us bind ourselves and every one of our heirs Executors and administrators jointly and severally firmly by these presents sealed and dated this 29th day of November 1790. The condition of this obligation is that whereas a marriage is shortly intended to be solemnized between the above bound William Bond and Sally Cranson of the County of Woodford. Now if it shall hereafter always appear that there is no just cause to obstruct this said marriage then this obligation shall be void or else to remain in full force. Test: Thomas Arnold William Bond Sherwood Knight |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed