|

Parts of the country are buried in snow. We’re demoralized by rain. Heavy, relentless rain. Cold rain. This past week we had two days of rain—occasionally with thunder--while the temperature stubbornly sat at 34 degrees. It has warmed now, but we’re back to steady, obstinate, pitiless rain. Roads are closed. Dams are holding back record levels of water. Topsoil and grass have washed away. Leaves leftover from late fall are matted to the ground in dense carpets, never having been dry enough to rake. The deer in our neighborhood apparently have little to forage. They stare in my front windows, lean over the porch railing, pleading for corn. Young calves are dying in the fields, stuck in the mud, frozen in cruel temperatures that never quite dip low enough to offer firm footing but are certainly low enough to bring on hypothermia. Once picturesque horse farms are vast mud pits, reminding tourists that these postcard-perfect stretches of land are still farms, wrestled into their summer beauty through the brute force and determination of committed men and women laboring behind the scenes. In 2018, we had 72 inches of rain, 160% of our average (45.21 inches). By December 1, it was already the wettest year on record. Then we had five more inches of rain before the year ended. In the first eight weeks of 2019, we have had 10 inches, almost double the average and on target for a year similar to last year. Don’t tell me you don’t believe in climate change. Don’t tell me that, all across the country, we haven’t seen extreme weather that has altered our lives, damaged our economies, and endangered our future. You may not agree with the specifics, or the vague generalities, summarized in the Green New Deal proposed by Democrats in the House and the Senate, but after years of inaction and denials, I give them credit for taking a bold first step. For at least trying to rivet our attention away from mopping basements, resodding lawns, digging cars out of snowbanks, fleeing wildfires and mudslides, standing in line for FEMA assistance, watching helplessly as the latest storm, the latest flood, the latest once-in-a-hundred-year event wipes out our homes, our businesses, our towns. Meanwhile, President Donald Trump is planning to establish a 12-member Presidential Committee on Climate Security to refute recent reports that climate change poses clear risk to our safety and our economy. Science and data be damned. Back in Kentucky, I woke up on Thursday morning and the rain had stopped. The sky was blue. The birds were singing. I had no idea where I was. We are so disoriented by these rapid changes in weather and climate—just as we are disoriented by new norms for civility and verbal expression and respect for our fellow man—that we have become numb to it all. Numb to the dangers. Numb to the costs. Numb to who we’re becoming. And that perhaps poses the greatest threat of all.

1 Comment

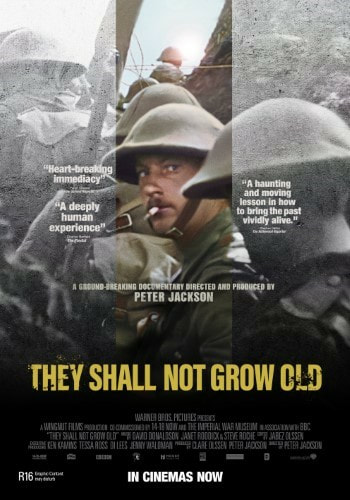

I don’t believe I’ve ever truly had writer’s block. Sure, there have been many, many times when I’d rather do anything other than the hard work of writing. But, once I finally convince myself to sit down at the computer, once I have some inkling of a topic or a scene in mind, I can usually put words on the page with ease. I suppose that makes me lucky. Or perhaps just a blowhard. My good fortune comes, I imagine, from the fact that I worked as a writer for many years under various sorts of deadlines. When your paycheck depends on it—or at least your professional reputation—you tend to find a way to deliver. For me, sitting down at the computer is a sign to get busy. The sooner I complete whatever ugly task is staring me in the face, the sooner I can get outside with the dog or tune back in to college basketball (at least this time of year). Of course, I also know that getting the words on the page is just a start. The fun part, for me, comes after that. I enjoy playing with words, upending sentences, moving the parts of the puzzle around to see what happens. I like to get my writing so “tight,” as some editors call it, that my fiction writing mentor used to call it “airless.” That might be a good thing for a press release or a technical manual, but that’s evidently not a good thing for a novel. So as I work on this book, I’ve had to learn to give the words room to breathe. I’ve had to give the characters time to fumble around with an idea or a thought. Their communication might not always be the most direct or the most efficient. It may well use more words—sometimes more colorful words—than the expression or the thought actually requires. That at times makes me very nervous. “Cut those unnecessary words!” I hear my invisible editor exclaim. “Make every word pull its weight. Murder your darlings!” But I’m learning that that approach can make for rather dull reading if you’re trying to create an interesting character. It’s been a tough lesson for me. I’ll discover soon whether I’ve figured it out. Meanwhile, I’ve been doing a lot of writing lately. That means my brain has been turned to “writing mode” nearly 24 hours a day. Last night, for example, as I lay in bed, I mapped out chapters and wrote snippets of text from 1:30 until 5 a.m. I got up a couple of times and made a few notes. Now, after a couple of hours sleep, we’ll see how much I can capture and actually use. That’s the disadvantage of finding writing a fairly easy endeavor. Once you turn on the spigot, it’s hard to turn it off. At the moment, though, I need my muse to keep working overtime. I have a deadline looming that I’m determined to make. That should keep me seated, focused, for a few more weeks to come.  By the time I was 14, I had read Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Pierre Boulle’s The Bridge Over the River Kwai, and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22. I don’t think I was particularly precocious or drawn to novels about war. These books just happened to be in my family’s library, and something I can’t possibly recall prompted me to pull them from the shelf. I’m certain I was a little young to fully appreciate the books, and I need to reread them all. But I can tell you that these fictional representations of two world wars both fascinated and repelled me. I was horrified by the realities and the inanities of war, and reading these books made me militantly anti-war at a very young age. As I prepared to write my own novel, I had to dig into each of these wars in a little more depth. The primary character, based somewhere between loosely and explicitly on the grandfather I never knew, served in France during World War I and accepted a job as a civilian at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland during World War II. I had already spent some time digging into WWII while David Hoefer and I were compiling The Last Resort. But, for the novel, I needed to know particulars, especially about the first few months of America’s involvement and how civilians responded to having the country engaged in yet another war. WWI was much fuzzier for me, so I’ve done some reading over the past couple of years to catch up. I also had the good fortune of multiple visits to an expansive exhibit about the war, curated by Margaret Spratt, at the Hopewell Museum in Paris, Ky., in 2017. And today I attended a screening of the cinematic wizardry that is the film They Shall Not Grow Old, Peter Jackson’s montage of original film footage transformed by vast teams of immensely talented technicians and then overlaid with excerpts from BBC interviews with soldiers who served during the war. The result is a powerful immersion in the trench warfare experienced by tens of thousands of soldiers, many of them absurdly young. I came away wondering what I always do when I gain a clearer understanding of the brutality of war: how anyone survives intact. I am by no means a scholar of these two wars. I do not have the depth or breadth of understanding of a curious high school student. But I have tried to grasp some kernel of truth about the sacrifices these men made and the moral lassitude that threatened their souls while fighting in a foreign land for reasons that weren’t always clear against men who in so many ways were just like them. If I have any hope of understanding my grandfather’s story, or my father’s story, I have to peer into that ugly maw, if only from the shelter of my comfortable armchair.  Rick showing off his new cast at Bluegrass Orthopaedics in Georgetown, Ky. Rick showing off his new cast at Bluegrass Orthopaedics in Georgetown, Ky. In mid-January, my husband, Rick, slipped on a muddy hillside while walking our dog and fell and broke his arm. It was a simple, clean break, only requiring a basic cast. But it radically—and immediately—altered the ebb and flow of his days. Rather than spending eight to ten hours a day at work moving heavy boxes of auto parts, he has found himself rattling around the house getting reacquainted with the TV, the washer and dryer, and his computer. He can stay up until midnight, if he chooses, and wake up when he wants. He can ponder home projects we’ve delayed for years, even if we both know we’ll never get around to tackling them. Some things haven’t changed. He and Lucy continue to take long walks, whether the temperature is 4 or 64. Tuesday nights he still joins the West Sixth Run Club, even if he’s walking rather than running. And, for those of you most concerned about whether he can still churn out hundreds of bourbon balls a week, fear not: he quickly adapted to one-arm candy-making. He also hasn’t been homebound. Despite the fact that both of our cars have a manual transmission—requiring two hands or, in Rick’s case, one very busy right hand—Rick hasn’t let his temporary disability keep him from his usual gallivanting. One evening he may head to Lexington for a music or cultural event. The next evening he’ll see what’s shaking in Frankfort. If it’s a day ending in “y,” there’s a bourbon celebration somewhere in central Kentucky. And Rick will most likely be there. As usual, he has taken this unexpected turn of events in stride. He prefers to think of it as “practicing retirement.” Meanwhile, I have also been navigating a shift in perspective. At the end of 2018, I decided to dedicate the first few months of 2019 to the novel I’ve been working on, with various levels of commitment, for years. I’m close—really close—to finishing it. I’m newly enthusiastic about the work. And I’m trying my best to ignore as many distractions as possible and devote my time to that singular task. To that end, I recently spent 10 days on a writing retreat in Minnesota under the hawkish eye of my newly minted writing coach, Tim Cooper. Together we scoured every word, every nuance, every historical fact in the first 20 chapters. He offered helpful criticism and much-needed encouragement. As a result, I have renewed confidence that I can get this thing done, and I have a clear plan to get there. Transitioning from writing nonfiction—in this blog, in op-eds provoked by national events, in materials related to The Last Resort—to fiction has not been easy for me. I’m comfortable writing about factual events and people’s individual and collective responses to them. I feel much more inept at imagining characters and scenes and conflicts and, most importantly, effectively rendering the emotions inherent in each. It has taken some time, and a lot of classroom instruction and mentoring, to help me understand how to capture the human condition, essentially, in words on a page, with the goal of evoking an authentic response from the reader. Rick may be comfortable behind the wheel of a car right now—reaching across the steering wheel for the turn signal, taking corners by alternately turning the wheel and shifting gears with the same hand—even if I’m not comfortable watching him do it. But I’m paying attention to him, trying to adopt his sanguine approach to an unexpected challenge. I think I can persevere. I hope the result will be a story worth reading. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed