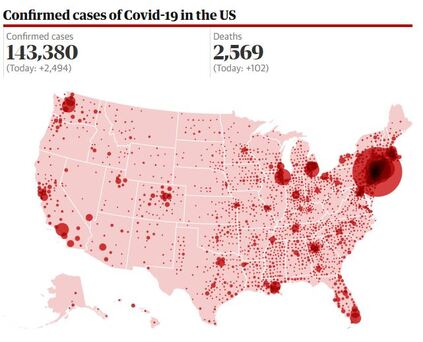

We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. It occurred to me recently that I’ve already heard from people in six states who have read Next Train Out: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Florida. I know that individuals in Georgia, Ohio, and New York have ordered the book. I have been thinking of the book as a “regional” novel, perhaps because of its settings in Kentucky, Ohio, and the Maryland coast. So I’m pleased to see its reach extend to New England, the Upper Midwest prairie, and our nation’s southernmost state. Though I confess that all of these readers have some sort of connection to Kentucky—however tenuous—I want to believe nonetheless that my limited data indicate the book has a wide appeal. That little survey of Next Train Out readers also made me realize that even during this period of social isolation we can share common experiences with far-flung friends and relatives, as well as people we’ve never met. I’ve delighted in the conversations and email exchanges I’ve had with those of you who have read the novel and have reached out to ask questions or offer critiques. We may not be able to meet for coffee or lunch, but we can still connect remotely and discuss something of interest to us both. In a much broader sense, I’m reminded that, while we’re in isolation, reading affirms our affiliation with greater humanity. Reading prods us to feel profound human connections with the characters in a book, however dissimilar we believe they are to us. While this worldwide pandemic might force us to become more self-centered in our daily routines, reading coaxes us to imagine ourselves in someone else’s situation. Faced with that character’s challenges, how would we respond? What would we do? How would we feel? In a time when the empathy of America’s citizens is once again being severely tested, it’s critically important that we look beyond our own perhaps small inconveniences and annoyances and consider the sacrifices and the heartaches of those around us. It’s impossible to turn on the television or check the news without seeing heart-wrenching stories of people who are ill, who have lost loved ones, who are tending to the medical needs of the sick without the necessary life-saving equipment, who are going to work every day to provide us with the goods and services that remain essential, who are struggling to patch together a precarious financial situation, who are wondering if the business they built will survive another month, who are fretting about their children’s education, who are struggling to stay healthy, both physically and mentally, during our voluntary home incarceration. How equipped are we, individually, to acknowledge their struggles? Do we fully recognize the need to change our habits to possibly keep someone else safe? Are we willing to make those little sacrifices? Reading widely helps train us for moments like these. It teaches us empathy. And compassion. It reminds us how small our own little world is. It reminds us that there are others with needs so much greater. In a recent article in The New Yorker, Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard, wrote: “Reading may be an infection, the mind of the writer seeping, unstoppable, into the mind of the reader. And it is also … an antidote, proven, unfailing, and exquisite.” In order, potentially, to reach an even wider audience—to spread “the contagion of reading,” as Lepore describes it—I have now released a Kindle version of Next Train Out. If you or someone you know prefers to read books on a tablet, e-reader, or other device—whether for convenience or to easily enlarge the size of the text—the Kindle version might be a good choice. It’s also an economical option for those watching their budget during these uncertain times. If you have read Next Train Out, I humbly ask you to consider writing a brief review of the book on Amazon. That may help other readers stumble across the title as they’re looking for a new diversion during our nationwide quarantine. I remain grateful for your interest.

2 Comments

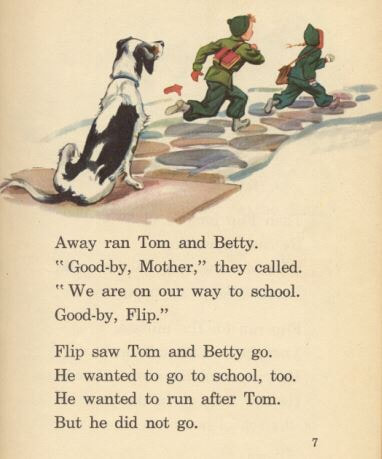

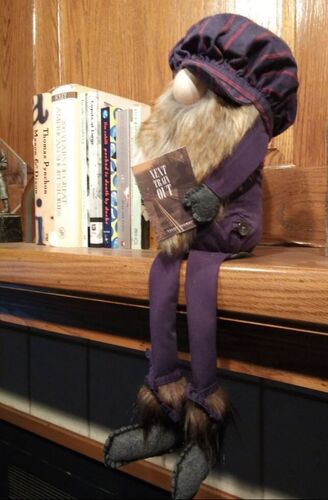

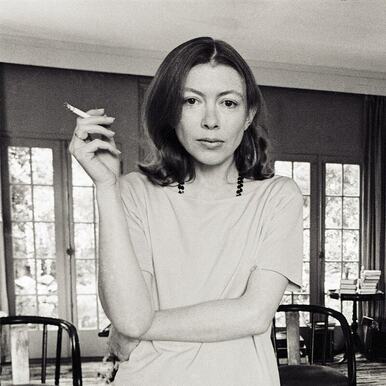

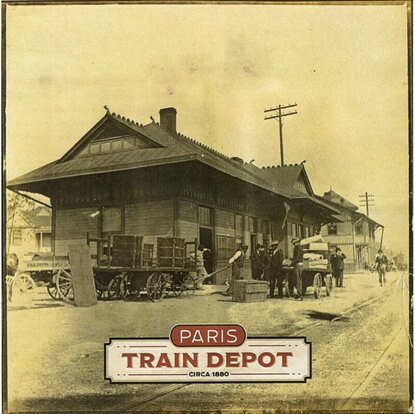

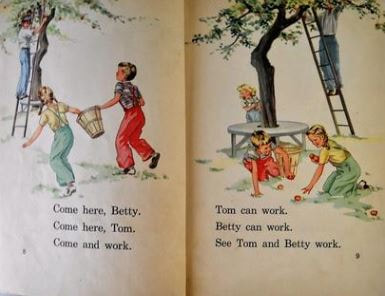

One of the riveting photos from “Celebrate a Community.” One of the riveting photos from “Celebrate a Community.” When I established Murky Press in the summer of 2017, it was originally a means to an end: I wanted to publish The Last Resort. And since I was already working on my novel, Next Train Out, I expected Murky Press would eventually have at least two titles in its catalog. But once the business was set up, I realized Murky Press could also provide a service for others who had a project they wanted to publish. I didn’t have a clear vision of how that might work, but it seemed a logical proposition to use the infrastructure and the experience I had gleaned to help others get their books in print. I’ve been so busy with my own writing that I hadn’t yet promoted this idea beyond casual conversations with a few folks I knew had projects underway. But back in December, I was approached by the two editors of Celebrate a Community, a handsome coffee table book that uses photos, historical documents, and well-researched text to tell the history of Perry Township and Fayetteville, Ohio. I began corresponding with Peggy Mezger Cooper, one of the book’s editors and a recent contributor to "Clearing the Fog," and we gradually put together a plan to reprint the book. They had depleted the copies from their first press run and were seeking a way to meet demand for additional copies at a reasonable price. I’m pleased to announce that the book is now available to all interested parties. You can read more about it on the Murky Press home page or order a copy from Amazon.com. If you are working on a book that you think reflects Murky Press’ mission, and you are searching for a way to get it published, get in touch with us. We may be able to help you find your way.  Who didn’t learn to read alongside Tom, Betty, and Flip? Who didn’t learn to read alongside Tom, Betty, and Flip? As many of us find ourselves with time to pick up a book, Peggy Cooper, of northern Kentucky, recalls first learning to read. Her ruminations may even inspire you to start putting words on a page. Peggy is the co-editor of Celebrate a Community, reprinted by Murky Press and available now from Amazon. It was 1960. I’d been ill and out of school because of some childhood illness. When I returned to school, there was catching up to do. Mrs. Johnson brought me to the front of the class so that we could do some work together while the rest of the class did other things. In the front of that classroom on a table perfectly sized for a first grader stood a huge book, a book that was taller than I was. I was going to learn to read. I knew my numbers and letters. I liked hearing stories and looking at the pictures in books. I liked school and Mrs. Johnson. She had taught my father when he first attended the one-room schoolhouse just south of Chasetown. He could read before he even went to school because he’d watched and listened and learned alongside his brother, John, who was two years older. Because he already knew first-grade learning, my father managed to skip that grade. I didn’t understand what I was supposed to do. It always helped to see other children do things first. Cousin Barbie, best friend and confidante, sat in the desk in front of my desk at school. She lived in town. She was wise in the ways of the world. She always knew what to do. We would talk and whisper and plan and play together. She was not at the table in the front of the classroom with me. I was lost, in more ways than one. Mrs. Johnson pointed to the picture in the book. The boy, Tom, was running. Yes, I could see the picture of Tom running. There were big black letters too. S-E-E. Yes, I knew those letters. What did those letters sound like? They sounded like an ess and an eee and another eee. How did they sound together? What did that mean, sound together? And what did Tom have to do with those letters on the page? Mrs. Johnson had been teaching for many years. In some way that now seems magical, she helped me make the connection between those letters on the page and how those letters could be put together to make words that told a story. I don’t remember how long she worked with me that day or over the next several days; I know it was a struggle. Mrs. Johnson knew how to help: SEE! See Tom. See Tom run! Then Betty joined the story, and Susan, and Flip, the dog. I could read! Triumph! Now I am putting letters on a page to tell stories myself. The stories, and the writing, are often like that experience of learning to read—a struggle to create meaning from a jumble of things that don’t seem to be connected. Sometimes the stories are about people who have lived and worked together and had a life before I was even born, remembered because it, the story, or they, the people, were significant in some way. Sometimes the stories are memories from my own life, savored because they were important to me. Sometimes the story evolves out of a photograph or a document, again, saved for a reason, and sometimes saved across generations. The essence of the story is the feeling it provokes, and often the meaning is caught up in the reason that the history, or the memory, or the photo or document, was saved. But, how to find that meaning, put it into words, and then share it? Feelings are elusive—and sensitive—things. Meaning is equally elusive, and personal. And the personal is, oftentimes, private, delicate, and special. A decision must be made—share or not? Struggle sums up the process. I’m still working on the triumph.  Everyone’s reading NEXT TRAIN OUT! Even this winsome locomotive engineer, handcrafted by my talented friend and neighbor, Lynne Craft. Everyone’s reading NEXT TRAIN OUT! Even this winsome locomotive engineer, handcrafted by my talented friend and neighbor, Lynne Craft. As a socially awkward introvert, I don’t always look forward to parties. But I was really, really looking forward to celebrating the release of Next Train Out with you. As I’m sure you have surmised by now, it is necessary to postpone our book launch party scheduled for April 5. We have also postponed my April 14 presentation before the Anderson County Historical Society. I am terribly disappointed. But none of us wants to play any role in inadvertently spreading this dangerous virus. We hope there will be a time later this year when we can come together and raise a glass of “Bourbon on the Tracks” in celebration. But now it is critical that we all heed the recommendations of our governor and the CDC and remove ourselves from society as much as we possibly can. The good news? It’s a great time to read! I hope you’ll consider ordering a copy of Next Train Out from Amazon. If you prefer, contact me here and I’ll mail you a copy. I’ll warn you that elements of the book may now hit a little close to home. There are references to the 1918 flu pandemic, as well as the 1929 stock market crash and its aftermath. I had no clue, of course, as I was writing the book how eerily familiar this period in our history might feel to contemporary readers. Since I can’t see you in person, I hope you’ll drop me a note or call to let me know what you thought. I’m finding that readers frequently are curious about what in my grandfather’s story is fact and what is fiction. I’ll be happy to pull back the curtain a bit if you’re interested. Finally, let me say, most importantly, how grateful I am for you interest. Please, do everything you can to stay safe and healthy during these trying times.  On Presidents Day (February 17), the Goodlett cousins gathered for a quick visit in Oldenburg, Indiana, oblivious to the dramatic shifts all Americans would face less than a month later. On Presidents Day (February 17), the Goodlett cousins gathered for a quick visit in Oldenburg, Indiana, oblivious to the dramatic shifts all Americans would face less than a month later. For three years I’ve looked forward to finishing my novel so I would have time for other things I enjoy: watching college basketball, attending chamber music concerts or literary events, having lunch with friends, traveling. You know where this is going. I am trying hard to maintain perspective on the grave threat our country—and, indeed, the entire world—is facing as the coronavirus spreads rapidly. I understand the exponential rise in cases demonstrated by the line charts we’ve all seen. I am taking this very seriously. So I’m only going to whine once: Why not while I was already hunkered down in isolation writing the book?! OK, I’m done. In reality, I am in an unusually felicitous situation. I do not have young children whose routines and education, not to mention safety or food security, have been upended. I do not work outside the home, so deciding how to fulfill my employment obligations without interacting with others is not a burden. I have no family members in nursing homes or assisted living facilities. As far as I know, I am healthy—even if I have now been defined as “elderly.” My risk of having a bad outcome even if I contract the virus is low. And I like being alone. I can readily entertain myself. I have scores of books here in my home that I have not yet read. I have big organizational projects around my house I have put off for years. I thoroughly enjoy walking my dog and paddling around the lake (if it ever stops raining). There is plenty to occupy me here. Nonetheless, even I—an affirmed misanthrope and regular avoider of social gatherings—am feeling the isolation. I think that’s in part because it came on so suddenly. Last Tuesday I was gathering with friends and family at a restaurant in Lawrenceburg. By Wednesday things were beginning to unravel. Today it would feel irresponsible to make plans for such an outing. I tend toward depression, and I could feel the darkness closing in at the end of the week. I took the actions I could to forestall it. I went for a long run on the beautiful Legacy Trail (in between rain showers). I cautiously attended a cycling class at my gym, trying to avoid the other participants and wiping down every surface I touched. I finished a book I had been reading. But I do have concerns about the mental health implications of this necessary social-distancing and the open-ended period of isolation we are facing. As entertainment options and our usual distractions become unavailable, where do we turn? As our social network narrows, how does that affect us? Are those with addictions at particular risk? Is anyone preparing for this next crisis? Many of you know that I’ve fretted over the years as we’ve shifted to online virtual connections and abandoned both casual and committed interpersonal interactions. The fears I expressed about social media in a 2016 op-ed today seem almost quaint. The norm is now to look down at our phones rather than acknowledge the presence of an individual we pass on the street—or someone sitting beside us at the table. It’s not just young people now who don’t know how to exchange common courtesies with a clerk or politely answer a phone call. We had already willingly moved toward “self-isolation.” How much farther will this pandemic push us? How will we recover as a human community, a community of individuals who genuinely need each other? I’m much more worried about that right now than I am about whether I can get toilet paper at the grocery.  Joan Didion in 1970. Photograph by Julian Wasser / Netflix. Joan Didion in 1970. Photograph by Julian Wasser / Netflix. Recently I had an insight into why so many women are writers. When men talk, women listen. When women talk, men walk out of the room. Turn off the TV. Look incredulously at the she-person who dared interrupt their brilliant interlocution. Come on, ladies. You know what I’m talking about. Sure, that’s an oversimplification. And I expect many men are totally unaware they do it. They’d be horrified if we pointed it out. But we never would. We’re too polite. Usually. But since the beginning of the written word, women have found our revenge. All those letters we wrote? All those diaries and journals we kept? All those underappreciated, and sometimes anonymous, reporters and novelists and poets and activists? All the women who fill the writing classes I take, eager to put on the page all those thoughts that have been stymied or crushed or tuned out? More and more these days I find myself keeping my mouth shut when I’m among a group of people. Or choosing not to venture out among people at all (a particularly valuable proclivity during this pandemic). Even during one-on-one interactions, I’m finding my best tactic is interested silence. As soon as I say something, I am doomed. But when I return to my computer, I can write it all down. There I can take the time to ruminate. To consider other perspectives. To do a little research, if I want. Or simply to sharpen my pen. Or my tongue. Then, if I choose to share my thoughts with others—either online or on the printed page—I don’t see you walk away. I don’t hear your insults or your disparaging comments. I don’t have to deal with your anger. In fact, I don’t really care how you react. I have had my say. And I am content. A writing instructor of mine once quoted Joan Didion during a memorable class: “In many ways writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It's an aggressive, even a hostile act . . . [T]here's no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer's sensibility on the reader's most private space.” [The italics are mine.] I was shocked. I wanted to dispute that. Slowly, though, I’ve come to realize just how honest a comment that is. Last week Elizabeth Warren spoke after she suspended her presidential campaign. Whatever you think about Warren, you have to acknowledge she has a lot to say. She thinks deeply. There is substance behind her plans. And she evidently enjoyed talking to the people at her rallies. She was good at spinning her tale of growing up in a family that was nearly left destitute when her father had medical issues—that is, until her mother stepped up and secured her first job at a nearby Sears store and rescued the family financially. Warren says she’ll have a lot more to say about what it was like running for president as a woman. I’ll be interested to hear her comments. I know a lot of people complained about her schoolmarm mannerisms or her histrionic delivery. A lot of people tuned her out. Walked away. And despite an early surge in the polls, her support eventually dwindled. I’m not sure she was ever at the top of my shifting list of preferred candidates, but I always respected her and, like with so many of the others running, I would have been perfectly happy if the nation had selected her as the nominee. We’ll hear more from her, though. She won’t be shy about writing another book. I expect she’s already realized how much easier it is to put a complete thought down on paper than it is to get heard among the human cacophony that surrounds us. I realize I’m old. And I’m tired. Tired of watching this same fight. Tired of watching bold women choke up as they describe the little girls they’re letting down because they couldn’t reach a goal they had promised those little girls was possible. I don’t expect to see any shift in my lifetime. But I do expect that, with the advent of self-publishing and easy access to the Internet, we will hear more and more from women who have a thing or two to say. If you let them into your private space, if you read their words, you may just find something of value.  In 2017, the Poynter family acquired the historic Paris train depot and began a careful and loving renovation of the property. It is now the Trackside Restaurant and Bourbon Bar, the site of our book launch party April 5. In 2017, the Poynter family acquired the historic Paris train depot and began a careful and loving renovation of the property. It is now the Trackside Restaurant and Bourbon Bar, the site of our book launch party April 5. I did it. Next Train Out is published. For those of you who have faithfully followed the twists and turns of my adventures writing a novel, this is supposed to be the sweet spot. The pinnacle. But I largely feel relief. And fear. What did I miss? What did I forget to do? Was I right to scale back Effie’s vernacular? Should I have expanded the story, given that there were so many more details to share? It’s time to find my way to acceptance. I am a severe taskmaster, but at some point I had to cut the cord and release this product of hard work and imagination to you. I hope it will find a few readers. I hope some of those readers will find Effie Mae and Lyons memorable. I hope the twentieth-century story will shed some light on the issues we’re still facing today. Thank you, again, for coming with me along this journey. Your words of encouragement and support are what finally got me to the finish line. If you decide to read the novel, I would be further indebted if you would consider writing a few words about your response to it on amazon.com. (Scroll to the bottom of the page to see where you can submit a review or a video.) Or send me your comments for a blog post. Either might encourage others to give it a look. Meanwhile I invite all of you to join us for the official book launch April 5 at the very train depot in Paris, Ky., where I have imagined Lyons first made the decision to turn his back on his family and his reasonably secure life. We’ll have music provided by Carla Gover—traditional Appalachian singer, songwriter, instrumentalist, and clogger—playing Effie Mae’s favorite music, and special food created by Trackside Restaurant’s chef John Wheeler to represent dishes evocative of the narrative’s historic period and geographic region. On April 14, I’ll be speaking about Lawrenceburg’s ties to the story at the monthly meeting of the Anderson County Historical Society. Everyone is welcome at both events. (Details) Many of you have asked, “What’s next?” My usual response: “Retirement!” I consider myself a “one-and-doner.” But Effie Mae’s words may better reflect what's in store for me: “It’s all part of life’s road map that I have no way of reading. I just take the turns as they come.” |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed