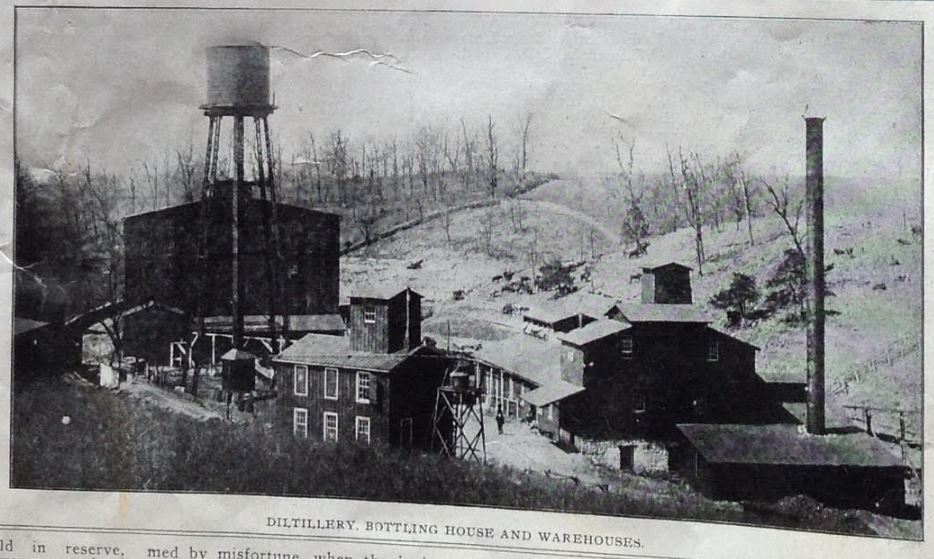

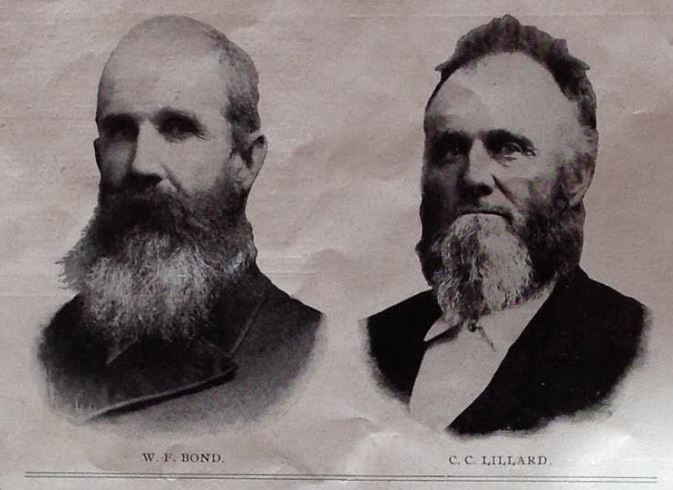

The remains of the Bond & Lillard bourbon distillery in Lawrenceburg, Ky. The elm tree is just visible to the left. (Photos by Rick Showalter) The remains of the Bond & Lillard bourbon distillery in Lawrenceburg, Ky. The elm tree is just visible to the left. (Photos by Rick Showalter) As we approached what remained of the Bond & Lillard bourbon distillery just south of Lawrenceburg, the first thing I noticed was the sprawling elm tree that towered over the lone wall that had withstood the battle. It was immediately clear that Mother Nature had once again asserted her dominance over the feeble constructions of man. In a 1906 “Souvenir Supplement” to the Anderson News, Lawrenceburg’s longtime newspaper, the unidentified author waxes poetic about the still thriving distillery perched in a lush natural environment: “As the traveler winds his way around [the lake stocked with fish and minnows] that leads to this plant, he is greeted by nature’s own sweet breath, spiked with mint, and the pungent and invigorating aroma of Bond & Lillard grown ripe and mellow.” At the time of this writing, in 1906, the distillery was owned by Stoll & Company of Lexington, who had purchased it from Mr. William F. Bond in 1899, after the 1896 death of Mr. C. C. Lillard, his brother-in-law. John Bond had erected the distillery on this site in 1836, drawn there by the nearby creek and a natural spring. Upon his death, his son David Bond managed the operation before being succeeded by his brother, William F. Bond, in 1849. William F. Bond forged the partnership with C. C. Lillard in 1869. The Bond history is what drew us to this site on a sunny, warm May morning. Bobby Cole, whose family owned the farm where he and Pud established Camp Last Resort, was a descendant of the Bonds. His two children, Bob and Julie, had wanted to visit this site redolent with their own history. Pud’s family had some tangential connections to the site, too. Thanks to a document preserved in a Bond family scrapbook, we had discovered that Pud’s great-grandfather, Hamilton Moore, had done some business with William F. Bond and his brother John W. Bond in 1856. It appears ol’ Hamilton, who had a reputation as a bit of a swashbuckler after his exploits at the Battle of Buena Vista during the Mexican-American War, was serving as a broker for a sizable whiskey transaction: $799.50 to transfer 1,818 gallons of “good merchantable whiskey” from William Bond’s warehouse to Mr. James Butts.  Hamilton Moore, Pud Goodlett's great-grandfather. Hamilton Moore, Pud Goodlett's great-grandfather. To add yet one more hue to Hamilton Moore’s colorful saga, family legend has it that, not long before he died at the tender age of 34, he was run off the family farm, about three miles south of the distillery, by his mother-in-law, Sally Morton Searcy. Evidently, Hamilton’s business dealings—or perhaps his reputation in general—were not well received among the others in his family’s long line of ministers. Ironically, Hamilton’s son, born just a year before he died, achieved more notoriety as a minister perhaps than any of his Moore or Hedger ancestors. Rev. William Dudley Moore, Pud’s grandfather, pastored numerous rural churches in the area and was both respected and beloved by many. He had also served as the local school superintendent. Perhaps he inherited just a bit of his father’s blood, however, for he made a trip to Mexico, to visit the site of his father’s battle, and he famously traveled to the Holy Land in 1911, when a trip of that type by a rural minister was nearly unheard of. While Hamilton died estranged from his family in 1857, four thousand reportedly attended the funeral of his son, Rev. W. D. Moore, when he died due to injuries received in a car wreck in 1935. Eight hundred automobiles joined the procession to the cemetery. I have to confess that the Goodletts I have known may have derived more genetic material from Hamilton Moore than from his son. Bourbon generally has a central role in family gatherings. Perhaps that is just a nod to our Anderson County roots, a show of support for an industry that allowed Lawrenceburg to prosper in the decades before Prohibition. More likely it’s a reflection of our search for shared conviviality or perhaps comfort amid life’s trials. As we’ve seen from Pud’s writing, nature presents another source of solace. In some ways, it was comforting to see the site of a once thriving family business overtaken by lush late-spring vegetation. It seemed the natural order of things. I think I found myself rooting for nature to teach us all a lesson about our own impermanence. Our lustiest human enterprises will all eventually yield to time. Perhaps the editor of the Anderson News had a similar thought in 1906. At the bottom of the article were a few words needed simply to fill the column. At first they seemed almost comically out of place following a story about man reaping the rewards of mastering his environment. But on further reflection, perhaps they’re intended to remind us of the perfect antidote to human hubris: “When in need of rest or recreation, seek out some quiet hamlet in Anderson, and there, under the shade of the magnificent forest trees, enjoy nature and be rejuvenated.”

9 Comments

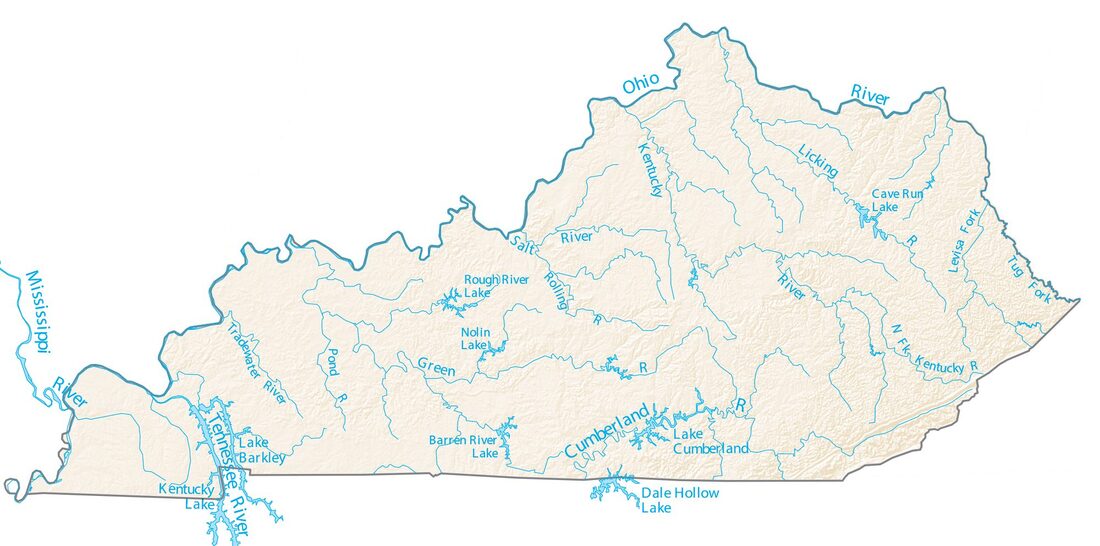

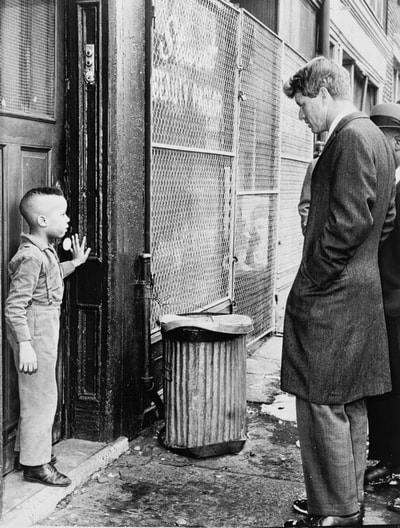

Kentucky's Salt River, site of The Last Resort camp (in Anderson County), and it's "west-flowing sister," the Green River. (https://gisgeography.com/kentucky-lakes-rivers-map/) Kentucky's Salt River, site of The Last Resort camp (in Anderson County), and it's "west-flowing sister," the Green River. (https://gisgeography.com/kentucky-lakes-rivers-map/) David Hoefer, of Louisville, Ky., is co-editor of The Last Resort and the author of the book's Introduction. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Kentucky is naturally a land of rivers. Every major pool of water in the state is a recent innovation of human engineering, a dammed-up and permanently flooded river valley that shares some, though not all, of the characteristics of a geologically formed lake. All these forays into large-scale landscape transformation were just getting underway when Pud Goodlett, Bobby Cole, and their buddies were participating in the much smaller-scale lifeways of Salt River during the first half of the 1940s. Rivers meandered through channels rather than rushing through canals; water was oxygenated by riffles and pools rather than the tailwater churn of turbines. The seasons of a temperate climate, marked by leaf color, flow rate, and other sense-catching variables, pressed directly on the dark ribbons of water threading their way through an abundance of interwoven plants and animals. One can imagine the unselfconscious bliss of immersion in this slow but dynamic pattern, as reflected in The Last Resort. The following video makes evident the steady march of change; it’s the Green River rather than the Salt, but the two are west-flowing sisters whose waters come to mingle in the mighty Ohio. Video courtesy of the National Park Service.  Robert F. Kennedy talks with young Ricky Taggart in the Bedford–Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn in 1966. Tim Cooper says, “My life is a weak attempt to live as Bobby Kennedy did.” Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. Robert F. Kennedy talks with young Ricky Taggart in the Bedford–Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn in 1966. Tim Cooper says, “My life is a weak attempt to live as Bobby Kennedy did.” Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. Tim Cooper of Oakdale, Minn., responds to last week's blog, The Healing Power of Green. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. I am recently returned from a weekend in a cabin in the vibrantly greening woods, in the sharply undulating mountains. By day, I hiked hardwood trails and climbed precipitous ascents, I scanned distant vistas and enjoyed the immediacy of identified and unidentified wildflowers, and I tried to put a name to, by sight or by sound, the abundant birds that sang me down my path. By late afternoon, I opened a bottle of wine and relished the isolation and rustic nature of the cabin. I prepared a sophisticated meal, and I planned the breakfast that would follow. At night, I lay down on a large, soft bed, and I heard the rain that stole into my domain without threat. I still heard distant birds, still felt the protective hug of the trees. And I fell asleep, and I did it all again, the next day. If I so chose, I could do something similar to this every weekend throughout the year. By choice, I am an urban dweller; I live in a major metropolitan area in the upper Midwest. By vocation, I am a teacher, and somehow, some way, I have spent my entire career in a suburban private high school, surrounded by wealth, privilege, and personal satisfaction. And by passion, I am a servant of social justice, a man who resides in an area of comfort and ease, and yet tentatively, feebly, extends my hands to those in need. Much of my journey in the realm of social justice has been as an advocate and direct care provider for the homeless. I still remember speaking to a man I had known for years who resided in a homeless shelter of last resort, the kind of place where Dinty Moore® Beef Stew and bread long past its expiration date were the evening meal, where a shockingly thin mattress placed six inches from a person you didn’t know was your bed, and where personal hygiene might have meant, if you were lucky, a small toothbrush and coarse soap. My conversations with Dick were deep, transcendent, and always instructional—he had a master’s degree in sociology from Northwestern University, but was transformed by Vietnam. On the particular night I remember, Dick told me that “alcoholism, drug addiction, violence, and rage are simply the poor person’s vacation.” He might have told me this as I was scheming about a weekend retreat to a cabin on the shore of Lake Superior. I’ve also served young children in inner-city public schools, the kinds of places where a classroom in reading or arithmetic has 45-50 students, and where personal assistance comes from people like me who come in to tutor. Deidra, a fourth grader and crack baby with a mom in jail for any number of nefarious arrests, once tried to stab me with a pencil out of sheer frustration because she couldn’t read the simplest texts. She, and other fourth graders I’ve met, has never seen an expansive green space, has had to navigate through slums where trash and dispossession form the core of her very being. At some point in my education, I remember reading that psychiatrists could not distinguish the brain formation of a Vietnam War veteran from a child raised and educated in an American ghetto. Dick, Deidra, my friends: I wish you could have seen the restorative, spirit-rejuvenating sites that I witnessed recently. My students take family vacations; it’s part of their very being. A cabin in the north woods, a Caribbean resort, a ski chalet in the Rockies…it’s all a part of their formation, their worldview. They are socialized to success, and they will be doctors and lawyers, they will be purveyors of business. They will attain graduate degrees, and they will pass this ethic on to their children. When I am particularly piqued at my students’ assumption that what they have is available to everyone if they just work hard enough, I chide them with the words “you chose your parents well.” I’m happy to say that most understand my meaning, and, perhaps, even a few agree.  I read with interest Sallie Showalter’s recent blog on the need for nature in our lives, “the solace of open spaces” to cite a favorite essayist, Gretel Ehrlich. Sallie’s reference to the psychological and physiological benefits of a natural setting reflects the very way we were both raised. Children of educated, vibrant parents, exposed to the beauty of nature and the arc of cultural wonder, Sallie and I both encourage everyone to tread lightly on this earth, to have a heart for the dispossessed, and to save spaces for both Dick and Deidra as they grope for a horizon. We chose our parents well.  Along a trail at Kentucky’s Natural Bridge State Park. The bridge is visible in the background. Along a trail at Kentucky’s Natural Bridge State Park. The bridge is visible in the background. It has been a spring riddled with grief. Two cousins, a close colleague, my husband’s uncle, a good friend’s mother, a neighbor I didn’t know well but who died so unexpectedly it sent us all reeling. That made getting out in the woods one day last week before the weekend deluge even more healing and restorative than usual. Hiking in Kentucky’s beautiful hardwood forests has always been high on my list of outdoor pleasures. I have to believe that some of my affinity for that activity was handed down to me from my dad—whether through genetics, through family picnics and camping trips, or through the endless hours of slides relating to his research he sometimes subjected us to. In the 1960s, most families viewed slides of birthday parties or other family gatherings. We sat quietly as he shared images of rock formations and treefall sites. In those days, children rarely had the chance to choose the family’s entertainment. Recent research has provided some evidence of a real connection between spending time in natural environments and reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. The Green Road Project at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., is currently attempting to measure these changes mathematically using biological markers such as levels of cortisol in the blood rather than the self-reported mood surveys commonly used in other research. Researchers involved in the project are particularly interested in understanding if time spent in a natural environment will promote healing among veterans suffering from PTSD or traumatic brain injuries. A more far-reaching goal of projects such as these is to offer community decision-makers objective evidence for championing local green spaces that improve health and well-being. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) produced a comprehensive report titled “Urban green spaces and health.” The report particularly focuses on how easily-accessible green spaces provide a respite from stress, a venue for physical activity, and an environment shielded from a city’s air and noise pollutants. The report concludes in part that “The evidence shows that urban green space has health benefits, particularly for economically deprived communities, children, pregnant women and senior citizens. It is therefore essential that all populations have adequate access to green space, with particular priority placed on provision for disadvantaged communities. While details of urban green space design and management have to be sensitive to local geographical and cultural conditions, the need for green space and its value for health and well‐being is universal.” My personal anecdotal evidence fully corroborates any conclusions correlating time spent in the woods and better emotional and physical health. Walking along a woodland trail, removed from the stressors and pressures of daily life, immediately calms you. The serene environment soothes you. The beauty awes you. Sometimes the experience even reminds you of our interconnectedness with nature and how we rely fully on the natural areas of this world for each and every breath. Which is why the disclaimer on the WHO report was more than mildly disturbing. I could just imagine the machinations behind the scenes before this report was published. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. I would like to think that our country’s questionably named Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) still cares about protecting our natural environments. But we have all come to understand that that is a naïve assessment of the agency’s role. So it’s up to us to protect these precious areas. I hope you will consider the small things you can do to help preserve the natural woodlands that support human life. And when you need relief from the vagaries of a sometimes cruel existence, I hope you, too, will wander a nearby woods and reclaim a sense of peace. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed