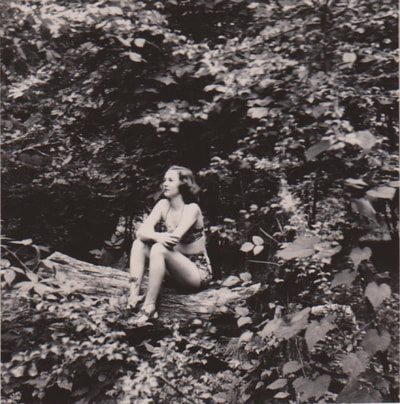

My cousins John Allen Moore and Bob Goodlett. My cousins John Allen Moore and Bob Goodlett. I come from a very small family. After my father died in 1967, it was my mother, my older sister, and me. My mother died in 1991. My sister lives hundreds of miles away. I quickly realized that I didn’t much like the feeling of being “untethered” from the mooring of a family. My husband has a wonderful, rather large family, but I wanted ties to folks who knew something about the people who had populated my early years, folks who could help me remember my parents and others of their generation and who could perhaps help me understand a little more about myself. So over the last three decades I have made concerted efforts to reach out to my many cousins, to invite them to my home, and to get to know them better. They are all older than I am, so I felt a bit like the annoying kid sister trying to wheedle my way into their orbits. Much to my relief, they have been largely tolerant of my whims, and I am immensely grateful for their ongoing support. My cousins are all fascinating people. Every last one of them. They intrigue me. They surprise me. There’s so much more I want to know about each of them. One of the unexpected benefits of publishing The Last Resort has been the opportunities it has created for me to connect with my extended family. While preparing the manuscript, I relied on them for information and family history. I had no choice but to call and ask them questions. In the process, I hoped to drum up their interest in the project so they would look forward to reading the book. What I didn’t predict was how the published book would open up conversations about family. I have heard stories that no one had thought to share before. I have discovered how many of my cousins had spent time at my dad’s camp on Salt River. I have spent hours traveling by car with two of my more intrepid cousins. Although the trips were long, the conversations we had were worth every moment of sedentary discomfort. Last weekend, the three of us visited two cousins in the Atlanta area: John Allen Moore, one of the original band of boys who joined Pud and Bobby Cole at The Last Resort in the early 1940s, and his younger brother, Joe Moore. We had seen them both two years ago as I was beginning work on this project, looking to them for information. This time I thoroughly enjoyed learning what footnote or story or photo in the book had piqued their interest. I eagerly anticipate continuing the conversations about family and mid-century life in Lawrenceburg and World War II. When you start a project like this, you think you can see where it will take you. You imagine holding the finished product in your hands. What you can’t fully anticipate are the unexpected personal connections and the emotions of the journey. Their breadth and depth have astonished me. And I might have missed it all if I hadn’t had the courage to reveal a family story and a family who would embrace it.

4 Comments

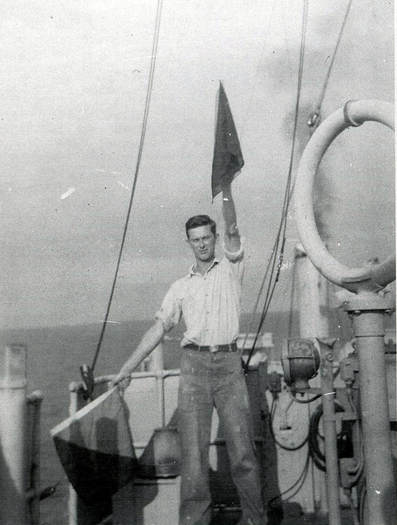

George McWilliams Jr. served as a B-24 navigator in the U.S. Army Air Corps; photo circa 1944 George McWilliams Jr. served as a B-24 navigator in the U.S. Army Air Corps; photo circa 1944 Bob McWilliams of Frankfort, Ky., offered the following as a comment to Joe Ford’s Unexpected Artifacts post. It generated such interest that I wanted to make it more widely available to Clearing the Fog readers. Pud Goodlett was a friend, fellow Boy Scout and classmate of my father, George McWilliams. As Sallie has mentioned, my dad camped with Pud and others at The Last Resort. Pud became part of my family when he married Mary Marrs, who was my Dad’s first cousin on his mother’s side. Mary Marrs and my dad were only children and they were the closest thing they had to a brother or sister. They may have even lived in the same house at one point in time. Growing up I heard stories about Pud and Dad camping and fishing at Salt River. Of course the fact that Pud and Bobby Cole built their own cabin by the river was for me about the neatest thing ever. In about 1964, my dad took my friends Bob Crossfield and Bill Stewart and me to The Last Resort for a camping trip. We were twelve years old. As was common, my dad let us explore and then left us for the night to fend for ourselves. The Last Resort was still standing then, though the roof had caved in as had most of the floor. The fireplace, chimney, walls, windows, kitchen, and front porch were intact. I made several return camping and fishing trips to The Last Resort over the next couple of years, camping under the stars and the trees. It was truly wonderful. On one of the visits I was sitting on the front porch when I noticed something partially concealed under the leaves and twigs on the ground. I picked it up and it was a piece of Masonite, painted chocolate brown. There was a ghost image of lettering on the board. I cleaned it up and could see that it said Last Resort. I knew then that there had been letters attached to it. I sifted through the leaves and found several pieces of straight wood, each cut from a sapling. Each one was approximately one-quarter inch in width and had been split in half lengthwise and varnished. The end of each piece was beveled. Some were longer than others and we took all the pieces and laid them on the porch floor on top of the Masonite board. To my shock, we were able to place every letter in its proper place, clearly spelling out Last Resort. We celebrated when the last piece of the puzzle was laid down. Alas, I left the sign there on the porch, not being able to project just how special this piece of family lore would have been to Mary Marrs, Ginny, and Sallie. I have tried to recreate the “twig lettering” in pen and ink to no avail. It seems I cannot recall how the curved letters were formed. I thought it would be a nice addition to Sallie’s book but I simply could not replicate it in decent fashion. When Pud passed away and Mary Marrs and the girls moved back to Kentucky, Mary Marrs gave me Pud’s L. L. Bean Maine Hunting Shoes, his backpack, snakebite kit, and snakebite boots. The latter had leather so thick and tough that a rattlesnake’s fangs could not penetrate the leather. It seems that I was the only one in the family who loved the outdoors to any degree and had feet small enough to wear the boots. Size 7 I think. Truth be known, I probably wore them for a long time after I had outgrown them. They were special gifts. She didn’t give me his machete, which was probably a good thing.  Photos by Rick Showalter, from a 2014 ice storm. Photos by Rick Showalter, from a 2014 ice storm. *Yes, that’s a direct theft of the title of Gwyn Hyman Rubio’s wonderful novel. My apologies, but perhaps it will inspire you to read it, or re-read it. Last week we had one of those Kentucky ice storms that creates an enchanted crystal wonderland without wreaking havoc on the roads or leaving thousands without power. By my estimate, the twigs and evergreen needles in my neighborhood were encased in a quarter-inch of ice, or perhaps a bit more. When I tried to walk the dog that morning, I discovered that every blade of grass had its own icy sheath. It was difficult to stay upright, especially with 70 pounds of dog muscle dragging me along. It remained cold overnight, and the next morning was absolutely magical. The sun came out for the first time in days and we were reminded that the sky can be a shocking shade of blue. On our morning walk, the sun backlit the trees along the eastern edge of the road, creating thickets of Christmas trees laden with shimmering tinsel. I was awestruck. I had to shade my eyes from the sun as I lingered to take in the view. On our afternoon walk, the trees on the western edge of the road were backlit, and the scene was completely different but just as startlingly beautiful. I hated to return home. The next morning it was gray again, and when we first headed out I thought it was raining. But I quickly realized that was just the ice inevitably melting from the trees as the temperature nudged above freezing. I know my neighbors are eager for spring after an already long and unusually cold winter. But I love this season, and I want to pay homage to it before it grudgingly gives way to the warmth of spring. I’m happy that we had a substantial snowfall back in January that shrouded the lake, the hills, and the woods in a peaceful white blanket. The backdrop made the deer and their normally camouflaged activities more visible amid the stands of hardwoods. Neighbors enjoyed a rare opportunity to lace up the skates, demonstrating varying degrees of skill as they circled the frozen lake behind my house or raced to the dam and back. Today, it's mud season. Two days of heavy rains have created new streams and ponds all around the neighborhood. The ground is so saturated it nearly swallows up my boots as I make my way across the sodden fields. This is the transition I dread, but I know it's part of the natural order. I couldn’t live somewhere without four distinct seasons. I seek variety in everything I do. I like change. And when spring finally does arrive, I’ll be just as thrilled by the blooming redbuds and the warm breezes as I have been by the frozen ground and the chickadees at my feeder.  The author's father, Jack Ford, U.S. Navy Signalman. The author's father, Jack Ford, U.S. Navy Signalman. After reading the blog post “Collecting Memories,” Joe Ford of Louisville, Ky., shared these memories of his father. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. I’ve been thinking about family “artifacts,” especially those that surprise rather than merely remind. My father was of the same generation as Pud Goodlett: he, too, interrupted his studies to go to war, returned to eventually get a Ph.D. (his in philosophy), taught college and engaged his students (in and out of the classroom), raised a family (eight of us), and like Pud had an impressive breadth of interests. He lived a long life, but even so there are these artifacts that surprise. I knew some of them existed, but never learned the story that would lessen the mystery of how they fit in with the fabric of his life. They are photos, physical items, even stories. I encountered them, new and old, known and unknown, after his recent death. A photograph of my father with Thomas Merton, John Howard Griffin, and Jacques Maritain. A pilot’s license. A hunting shotgun we kids would surreptitiously pull out of the attic and admire. A trumpet in a case lined in red velvet. A small box containing the relics of three saints. Every “Calvin and Hobbes” book ever published. And an oft-repeated story from his good friend Jim Henry describing the first time he met my father: he came down the steps of a Navy ship and there sat Jack Ford at the bottom, reading Aristotle. Yes, yes, I knew he rubbed shoulders with those Catholic thinkers, had a sense he flew before I came along, had a vague notion he hunted (there was that gun in the attic, after all). But a trumpet for a man who was seemingly tone deaf? No idea. The relics—with authentication records, no less? Total mystery. But what are the stories behind the artifacts? Why did they all come, those men, that day, to Merton's hermitage? How did someone of such modest means learn to fly and why did he give it up (other than those students in our basement throwing up after a flight)? Who taught that city boy to hunt? What did those relics hold for a rigorous, philosophical mind? And how does it all weave together for a man who lost his father at an early age and had a difficult childhood, yet found deep satisfaction in his life and family and students? We look to artifacts to bring meaning, to fill out memories, to explain. Some do. But some only give a sense of the richness and inherent mystery of a life. In The Last Resort, Sallie Goodlett Showalter took a rare opportunity to explore and understand at least a part of her father’s life. She could have pointed to the fly rod in the garage and remarked that he had a fishing spot with some buddies on Salt River. End of story. Just some stuff, some artifacts. Instead, she and David Hoefer have brought his journal to life, a journal that touches and reflects many lives, and I am sure the research and conversation and countless artifacts have enriched her far beyond what she expected. For all of us, in all of us, there is still mystery. Go, surprise. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed