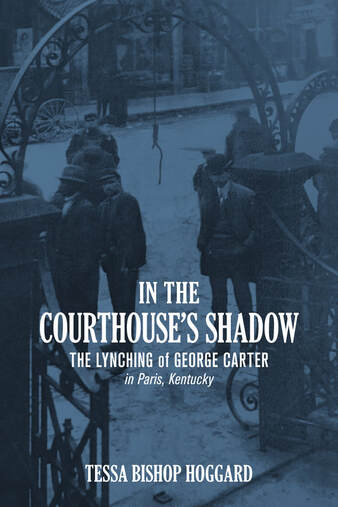

Tessa Bishop Hoggard with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of a lynching victim, George Carter. Tessa Bishop Hoggard with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of a lynching victim, George Carter. She spent years researching his family. She wrote and published a book examining the tragic story of his great-uncle. She arranged for him to meet a descendant of the woman who brought enormous grief upon his family. But she had never met him in person…until this week. Tessa Bishop Hoggard is on a mission. She recently traveled from her current home in Texas to her hometown of Paris, Ky., to round up support for her latest project: erecting a historical marker near the Paris courthouse where two Black men were lynched, in 1866 and 1901. The proposed marker will also honor a third man who was lynched nearby in 1889. Tessa’s purpose is clear: She wants to ensure that the citizens of her hometown—the old and the young—have the opportunity to confront the truths of its past. She is certain that only through acknowledging our dark history can we heal as a community and as a nation. So far her trip has been a success. After sending numerous emails and letters to local citizens and officials over the last year, she is finding that a brief face-to-face encounter seems to seal the deal. “I came prepared to recite the history of each of the three lynchings, to introduce these officials to the specific story of each individual,” Tessa told me. “But that hasn’t been necessary. As soon as they learn what I am proposing, they are offering support. I am truly flabbergasted. And elated.”  One of those victims of mob violence was Jim Bannister’s great-uncle, George Carter, who was hung on the iron gate in front of the courthouse in 1901. Carter was the older brother of Jim’s grandmother Katie—the woman who raised him. Two photos of Carter’s body hanging from the noose still exist and are reprinted in Tessa’s superb book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky. Those photos, and the newspaper description of the original incident that eventually led to mob violence, raise suspicions about whether Carter was even involved in the alleged “assault” of a local banker’s wife, Mary Lake Barnes Board, my great-grandmother. Initial reporting described the incident as an attack by “a negro man, who attempted to grab her pocket-book.” [The Kentuckian-Citizen, Paris, Ky., December 5, 1900] Many of you already know the story of how Tessa arranged from afar for me to have a public conversation with Jim Bannister in 2020. That conversation offered him an opportunity to express his grief and his frustration at not being able to uncover the truth of his great-uncle’s story, as well as his relief that it was finally being aired in public. It offered me a chance to publicly voice my regret for the horror his family endured and my apology for the role my family played in what took place. This week Tessa, Jim, and I gathered together for the first time. Emotions ran high. We took turns expressing how profoundly grateful we are for all that has transpired in the last two years. We hugged. I shed a few tears. Jim and I talk fairly often (we have to dissect Kentucky basketball on a regular basis), and I have seen him a handful of times, despite the challenges of the pandemic. But he and Tessa were in the same room for the first time. It was breathtaking to witness. In early 2023, Tessa will submit her application to the Historical Marker Program of the Kentucky Historical Society. It appears her trip this week has accomplished her goals: she has met with local officials, she has solicited letters of support, and she has revisited the scene of these tragic extrajudicial hangings. She also met George Carter’s great-nephew for the first time.  Sallie Showalter, the great-granddaughter of the woman allegedly assaulted by George Carter, with his great-nephew, Jim Bannister. Jim is holding his school photo from 1947-48, which Tessa found in her late mother’s belongings. Tessa’s interest in George Carter’s story was ignited when her mother shared a newspaper clipping she had kept from 1978 retelling the story of the hanging.

1 Comment

With my cousin Sandy Goodlett, who died in April 2021, my cousin Joe Moore, and his wife, Jean. In Atlanta, August 2015. Photo by Robert Goodlett. With my cousin Sandy Goodlett, who died in April 2021, my cousin Joe Moore, and his wife, Jean. In Atlanta, August 2015. Photo by Robert Goodlett. When I was a sophomore in high school, my mother decided for a number of complicated reasons to send me to a boarding school in Virginia. Nestled at the base of a mountain in the Shenandoah Valley, it was the perfect place for me. I could canoe, camp, ride horses, play tennis, and even join a synchronized swimming team. Classes were tiny: typically five or six students, maybe 12 in my biggest class. We got to know our teachers personally. After overcoming initial loneliness, I made some friends by the end of the year. Sadly, that was the last year the school, which had been in operation for nearly 100 years, was financially able to stay open. A number of my classmates chose to attend similar schools in the area. For some reason, inexplicable to me now, I decided to try something completely different: a large urban school in the swanky north end of Atlanta that accepted only a few boarders, largely international students. It was an academically competitive school, and I devoted hours every night to homework, rarely finishing before the wee hours of the morning. The Southern norms and mores mystified me. I joined the marching band and the volleyball team, but otherwise completely isolated myself. I was miserable. I became anorexic, starving myself both to avoid solitary meals in the cafeteria and in a vain attempt to exert some control over an immensely painful situation. When I dropped to 82 pounds, even the women who cleaned the dorm were asking me about my health, expressing genuine concern. I batted away their inquiries. At my previous school, I couldn’t avoid knowing that a number of the girls purged after meals. One in particular, a friend of mine whose room was across the hall, was a competitive figure skater from Wisconsin. She didn’t come back the second semester, and I heard through the grapevine that alcohol and bulimia had landed her in the hospital. The public was just becoming aware of eating disorders and their toll on young women and their families, but I couldn’t imagine myself falling victim to such self-abuse. Then my circumstances changed. My dad’s first cousin, Joe Moore, lived in Atlanta, and he and his wife, Jean, periodically brought me to their house or took me sightseeing around the city. They gave me a taste of normalcy. I was deeply grateful to them for taking me in when I most needed to feel welcome somewhere. I doubt I was able to express at the time what their kindness meant to me. At Christmastime that year, my mother recognized the severity of my illness and didn’t let me return to Atlanta. With her quiet, non-pushy supervision, comfortable in my own home, my health improved. A few years ago, my cousin Sandy Goodlett helped me reconnect with Joe, his brother, John Allen, and their sister, Jane. We made a couple of trips to Atlanta and Owensboro, Ky., and relished the family stories they could share with us. Having lost my father at a very young age, I was always thirsty for details about my dad from those who knew him best. On Sunday, January 9, Joe’s wife, Jean, died of complications from Covid and increasing dementia. She was fully vaccinated but still vulnerable at 83. As I work through my own sadness, I realize it’s tied to the kindness she extended to me in a time of real distress. A new year, more time to grieve. This virus is not done with us. We’re still losing more than a thousand Americans each day. Each victim leaves behind a loving family and friends. We know this. It sounds trite. But we should not forget it. We should not get complacent. And we should not decide it’s OK to sacrifice the aged and the vulnerable so we can blithely go about our lives without disruption. We must take the simple steps that we can to limit the virus’s spread: get vaccinated and boosted, wear a mask, avoid large crowds. That is not asking too much. The piercing shriek launched me from my position reclining on the sofa. I had landed there moments before after relinquishing my spot in the bed to my elderly dog, her whole body shaking in distress from the thunder and lightning and pounding rain. Was it the smoke alarm? I sniffed. No detectable smoke. I stumbled toward the sound. My cell phone was on the kitchen table, practically bouncing from the urgency of its alert. “Tornado Warning,” I saw on the screen. The phone rang—an old-fashioned ring from a land line—and when I picked up the receiver, I heard this simple message: “Tornado warning. Take cover.” I raced back to the living room, just as the siren near the front of our neighborhood began to wail. I turned on the TV to a local channel and heard, “The possible tornado is directly over the city of Frankfort heading toward northern Scott County.” That’s where I live.

I called out to Rick that we had to go to the basement. I dragged Lucy down the stairs and into the interior bathroom, grabbing my cell phone and a flashlight as I went. I turned up the TV in the basement to hear the reports and kept the bathroom door ajar. I heard Chris Bailey of WKYT say, “If you have a helmet—a batting helmet, a bicycle helmet, anything—put it on. Protect your head.” I made a mental note to store those old bike helmets in the bathroom. Then, “The suspected tornado is moving toward Peak’s Mill on its way toward Stamping Ground and Sadieville.” We were directly in its path. I watched the radar on my cell phone. The storm was moving fast. In a matter of minutes, it appeared the worst of it was skirting the northern edge of our neighborhood. And then it was gone. We escaped again. Although Stamping Ground, a small community in western Scott County, had suffered extensive damage from a smaller EF1 tornado just five days earlier, no other nearby areas were significantly affected by this storm. It was not until early Saturday morning, when I turned on the news, that I had any idea of the extent of the devastation to Kentucky and surrounding states. It’s almost a cliché, but tornadoes in particular make you wonder why you, your loved ones, your home were spared when others lost everything. In communities like Bowling Green, where the tornado made a more traditional swath of destruction, news images show one house demolished and the one across the street still standing, relatively unharmed. In Mayfield, unfortunately, there seem to be few random “lucky ones.” The storm appears to have annihilated most of the town. Many lives have been lost. As I type this, families are still searching. The grief and horror are immeasurable. The trauma to these communities will endure. The costs to rebuild will swell. Yet back in Scott County, the sun is shining and the sky is a brilliant blue. The crisp air invites you outdoors. The winds are finally calm. It’s hard to reconcile this pristine day with what I know has happened a couple hundred miles west. I’ll save my screed on climate change for another day. Today we are all thinking of those affected by these storms. Today, once again, I am wondering why my life has been left intact, as the wheel of fate continues to turn.  June Camp made this bracelet from safety pins, gold elastic thread, beads, and buttons. Photo by Lynne Craft. June Camp made this bracelet from safety pins, gold elastic thread, beads, and buttons. Photo by Lynne Craft. My dear friend and neighbor, Lynne Craft, recently sent me the following message: When I dressed for my family’s Thanksgiving celebration, I put on the bracelet that June had given me several years ago. I have thought a lot lately about the hours she and I spent making those bracelets and laughing together while you and Chuck were out biking or visiting on your back patio. I got to know her well as she shared her crafting techniques with me. She was a beautiful soul. My two grandsons were both intrigued by the bracelet. Miles, the seven-year-old, couldn’t believe it was made of safety pins. I took it off and he carefully examined the construction. Then he said, “This is sooooooo cool. Momma uses safety pins to hold our clothes together when they break. How did you make this?” I told him a very dear friend of mine made the bracelet and gave it to me. She then taught me how to make them. He asked, “On our next sleepover, can we make one for Momma?” It was so sweet, I couldn’t help but get choked up. I told him we would, and he could give it to her for Christmas. If you ever wonder what legacy you will leave behind when you depart this earth, take a moment to examine the everyday interactions you have with the friends and family who move through your life. It may be the smallest gesture, a simple word, a seemingly insignificant shared experience that reverberates for generations to come. It may be your own grandchild or relative who stows away a memory of you that influences who they become or how they carry themselves in the world.

Or it may be a youngster you have never met, who was not yet born when you were friends with his grandmother, who internalizes your kindness and wants to mimic your talents so he can bestow his mother with a special gift—a gift that she may later share with her own grandchild. June, our former neighbor, recently succumbed to cancer after a long and difficult struggle. A few years ago she and her husband, Chuck, had moved to Massachusetts to be closer to family. It was hard for those of us left behind to be aware of the decline in her health while being so physically removed and unable to help. But her spirit has clearly not left us, and moments of her life will be cherished by those who knew her—and even some who didn’t. Our human engagements are as complex as the construction of that bracelet, and sometimes as tangled and inscrutable. We can’t always recognize our influence or the sway we hold. When we’re at our best, in fact, we don’t worry about how others perceive us. We forget that they’re watching. Upon inspection, our lives are a collection of ordinary moments strung together to fulfill largely ordinary goals. The extraordinary is rare, and perhaps unnecessary. As we piece together our personal histories, we make mistakes, undo errors, are surprised by unexpected pricks to our ego or our conscience or our sense of self. But the body of work we leave behind can only be discerned by those who loved us. What matters is not really for us to decide. As we relish time with family and friends during the holidays, I encourage you to focus on the little things—the laughter with a friend, the solace offered to one who grieves, a safety pin produced to mend a tear—rather than worrying about the lavish spectacle or the ostentatious gift. What may seem inconsequential to us today is what may eventually define us.  Running relatively pain-free in November 2021, at The Gobbler 10K north of Lexington, Ky. Photo by JA Laub Photography. Running relatively pain-free in November 2021, at The Gobbler 10K north of Lexington, Ky. Photo by JA Laub Photography. “I didn’t know what it was like to live pain-free until after…surgery. I was so much more productive. I was so much more calm. I could think clearly. And it made me mad because I realized that this treatment I got at 36 should have happened in my early 20s. As women, you just want to have an equal opportunity at achievement that your male counterparts do, but if you’re saddled with such a severe…issue, you’re starting from way back behind the starting line.” —Padma Lakshmi When I read these words from author, actress, and television host Padma Lakshmi in a recent Parade magazine supplement that came in my newspaper (yeah, the ones constructed out of newsprint), I nearly stopped breathing. I had heard Lakshmi’s name, but I am not a foodie and I knew nothing about her. I’ve never seen her shows. I was not aware of the essay she wrote for the New York Times in 2018 speaking out about her own sexual assault after Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court, or that she is the American Civil Liberties Union ambassador for immigration and women's rights. I did not know she was once married to author Salman Rushdie. But here was a celebrity with a huge following voicing publicly one of my most deeply buried secrets. If she said it out loud, I decided, I can too. No one but my husband knows how I suffered for decades from undiagnosed endometriosis, and he only had a vague notion of how it affected my ability to function normally. I never missed a day of work or school because of it, although I did leave each early once, 25 years apart, when I nearly passed out from the pain. I barely remember a classmate leading me to my high school’s office so someone could call my mother after I had nearly slid out of my chair during advanced math class, half unconscious. That day my doctor gave me a shot in the hip of some sort of potent pain reliever. No one had any idea what to do with me. In my 40s, I discovered that my body would go into “labor” 14 minutes into an intense run, such as when I was racing. It was like clockwork. Evidently, I finally surmised from my own research, the adrenaline rush kicked in a whole series of hormonal reactions. I usually made it to the finish line, where I would crawl into the bushes somewhere and crumble into a fetal position until the pain subsided. Then I would be fine. Like Lakshmi, I consulted doctors annually about my troubles. I was soothed and patronized. My mother had been prescribed Diethylstilbestrol (DES) when she was pregnant with me, a nonsteroidal estrogen given to women in that era who had trouble carrying pregnancies to term. In 1971, the FDA withdrew approval of DES as a treatment for pregnant women. The medical community calls me a “DES daughter.” I have known since puberty that I was at high risk for gynecological cancers and related issues. Endometriosis is common. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, it affects an estimated two to ten percent of American women between the ages of 25 and 40. It causes immense suffering and infertility. Yet rarely do people talk about it. To address its near invisibility, Lakshmi co-founded the Endometriosis Foundation of America to promote early diagnosis and intervention and to better inform the medical community and the public about the disease. Lakshmi was 36 when she first found relief. I was 49. When the pain started persisting for up to 25 days a month, my doctor finally recommended exploratory surgery. I gladly assented. Evidently there are no adequate imaging tests to identify the scar tissue that twists and binds the abdominal organs when the endometrial tissue begins to grow outside the uterus. After the surgery, the doctor found my husband in the waiting room and showed him pictures she had taken of my bladder and bowel and ureters and appendix and fallopian tubes all bound together in a sticky mess. He promptly passed out. I found him lying on a gurney next to me when I awoke from the anesthesia, being pampered by the nurses who were offering him cookies and orange juice. I had major surgery a month later. The relief was nearly immediate. Within a few months I left behind a part-time job that was all I could manage at the time and accepted a big new job that I knew would challenge me. I was up for it. Like Lakshmi, I felt calmer, more capable, better able to handle whatever life threw at me. My career took a distinctive turn that eventually led to Murky Press. I can’t imagine any of that happening without that surgery. Like Lakshmi, I have frequently, quietly, reflected on why I couldn’t get help earlier. I have dealt with the anger. But, as Thanksgiving once again approaches, I am thankful that my health dramatically improved 12 years ago. The absence of pain allows us to forget, but reading her story reminded me of how different my daily existence is now than it was for nearly 35 years of my life. So this week, with Lakshmi’s prompting, I am celebrating good health. I am celebrating a decade of embracing bold actions. I am celebrating the kinder, gentler attitude my good health has permitted me. And as the niggling aches and pains of old age fail to completely quash my good spirits, I am celebrating more good years to come.  Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., reflects on how to move forward after a painful disruption. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. “My books are friends that never fail me.” —Thomas Carlyle When crisis enters our lives, some of us head to the cookie jar, some to the TV remote, others out into nature, to phone a trusted friend, or possibly to some sort of substance to numb the pain. I am one who heads straight to the bookstore. I begin to look for answers, insight, explanations, and causes for my plight in the words drawn from someone else’s experience or expertise. I generally believe I cannot go through something that someone else has not already lived through and learned from. Often, some of those people have graciously taken pen to paper, or fingers to keyboard, and provided me with a book in which I can find solace, advice, and confirmation that I am not alone in my struggles. At present, I am going through a divorce, which was preceded by about a decade of my 27-year marriage unraveling slowly and painfully. Once the plan changed from working to reconcile and rebuild the relationship, I donated my stash of a dozen or so books about how to save/repair/improve a relationship. Likewise, I’ve recently acquired (so far) six titles on self-love, adult attachment styles, unlearning patterns and beliefs from childhood, attracting a well-suited life partner, essays to change the way I think, and a workbook for healing. I’m sure this new collection will continue to grow. I recall that when we first started dating, one of our favorite places to go for a night out together was the gigantic Joseph Beth Booksellers in Lexington, Ky. I guess I have come full circle in “completing” that relationship. Before making the decision to split permanently, we attended copious therapy sessions with four (!) different marriage counselors and invested much time, effort, and funds attempting to repair what ultimately has been deemed “irretrievably broken.” While I can’t help feeling deep sorrow at choosing to end such a long-term relationship, I am (finally) certain it is the right decision. So, I am trying to focus on the incredible growth that came from the lessons learned during the difficult times, and the grand opportunities this new, unexpected, chapter will offer me. I also occasionally remember with gratitude the many good times we shared, and that our union resulted in three wonderful new human beings. The ending of this, or any, marriage is not altogether a failure. Through all the therapy, and attempts to reconcile, I’ve become much more self-aware. I’ve had to reflect on the part I played in the dysfunction and the dissolution of what once seemed a rock-solid bond. There is no doubt in my mind that my soon to be ex-husband has been one of the greatest teachers of my lifetime. I know I am a stronger, smarter, more resilient, and more compassionate person as a result of our tumultuous marriage. I predict the divorce process will earn me even more knowledge, skills, and tidbits I never asked for, but surely need for my journey. I try to remember my current situation represents a tiny slice of what makes up the rich, tasty pie of my greater life experience. While divorce defines a part of my reality right now, it does not define me. Rather than dwell on the fact that I am walking away from something unhealthy, I’m choosing to see myself as someone stepping out into the light on a bright new path forward. Along this detour, I’ll continue to learn more about myself and strive to live my best life as the days continue to unfold. I’m choosing to take care of myself. I’m choosing happiness and contentment. I wish I could say I never experience the pain of euphoric recall, and that I never shed a tear mourning the loss of what I thought we had. While I am strong, I am not a stoic. From all that therapy, and my trusty books, I have learned that feeling and acknowledging my emotions and letting them move through me, rather than denying them and soldiering on, makes me a more complete human being, a more grounded, compassionate (and sane) person. I’m hopeful that someday I may find another partner to love and share life with. In the meantime, I’ll keep visiting the bookstore and continue learning how to improve my skills at navigating this life, so I can be an even better potential mate. It’s probably a good idea to add some fun fiction to my collection, too. After all, we can always use more friends.  My mother, Mary Marrs Board Goodlett, would have celebrated her 100th birthday on October 26. My mother, Mary Marrs Board Goodlett, would have celebrated her 100th birthday on October 26. On October 26, 1991, a sunny autumn Saturday, we threw a small party for my mother’s 70th birthday at her modest home in Georgetown, Ky. Esophageal cancer had nearly stolen her voice, but she managed to engage with a few friends and relatives. After a short while, she retreated to her recliner in her bedroom and evidently decided she had fulfilled her earthly obligations. Sixteen days later she died. At her funeral, during the eulogy by Rev. Bob C. Jones, her longtime pastor at the Lawrenceburg First Baptist Church, I learned that she had told him she wanted to live to be 70 years old, the length of a life as stated by King David in Psalm 90:10: “The days of our years are threescore years and ten.” (King James version) I remember thinking at the time that I sure wished she had shared that goal with me. As her primary caregiver, if I had realized she was committed to making it to 70, perhaps I could have planned things a little better during those last weeks, or made better decisions. Now the 100th anniversary of her birth is nigh. And I have been thinking about her a lot. I cannot tell you how frequently I have wished for her wisdom over the last 30 years. When I was 30, I was too young and self-absorbed to inquire about her life, her experiences, her challenges, her sorrows. By the time I was 32, she was gone. But I learned a lot from my mother watching her die. I am grateful for that. If you’ll indulge my somewhat morbid mood, I’ll share my mother’s unspoken doctrine for a graceful exit, as divined at the time by her grief-addled daughter:  My mother’s final birthday party, October 26, 1991. Our lives are as ephemeral as the flowers on the table. My mother’s final birthday party, October 26, 1991. Our lives are as ephemeral as the flowers on the table. 1) Leave this world as quietly as you traveled through it. Although my mother was evidently a gregarious young woman, by the time I knew her she seemed most comfortable with a good book and a glass of bourbon. She was not one to make a fuss about anything. She left us as gently and simply as she had lived. I suppose the corollary of that might also be true. If you have been inclined to make a ruckus all your life, you will probably make a ruckus as you slam the door behind you for the last time. 2) Maintain whatever dignity you can. Although sickness and dying infamously heap myriad indignities on you, hold tightly to whatever scraps of your dignity you can. If you still have your wits, treat those around you—both loved ones and medical professionals—with the kindness and the respect they deserve. Make ribald jokes to break the tension during uncomfortable moments. Encourage laughter. 3) Stay engaged with the wider world, even if that means watching Clarence Thomas insult and demean Anita Hill during Congressional hearings. Stay curious. Take interest in things outside your own sometimes harrowing situation. 4) Things really don’t matter. I was in that “acquisitive” phase when my mother died. I had already acquired a husband and a dog and a house, and I was busy acquiring all the other accoutrements of a middle-class adult existence. In her final months, I kept wanting to give her something she had always wanted, but that list for her had been empty for years. I recall that I found our contrasting attitudes jarring. I was both annoyed that I couldn’t give her something she might fleetingly treasure in her final days and ashamed that I would confer that sort of value on something I could buy. We rarely have a choice about how this life ends. But every moment we’re still here we have a choice about how we live the one we have.

Happy birthday, Mary Marrs.  John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett with his beautiful bride, Mary Marrs Board, December 27, 1947. John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett with his beautiful bride, Mary Marrs Board, December 27, 1947. I’ve never liked Father’s Day. My father died unexpectedly when I was seven, and I’ve felt cheated ever since. I could happily wipe that holiday off my calendar. This year, however, marking Father’s Day is putting a smile on my face. Recently, my cousin Bob Goodlett had some iconic family video digitized to share with relatives near and far. Today, I’m sharing my Father’s Day joy with you. It turns out that my Uncle Leonard Fallis, husband of my dad’s older sister, Virginia, had an 8mm movie camera as early as the 1940s. I don’t recall ever having seen the following clip before Bob shared it with us last month. But there’s my father, before the war and all the horror he witnessed, strutting around his family’s property in Lawrenceburg, Ky., in his University of Kentucky ROTC uniform, being silly, mugging for the camera, while his faithful dog, Mike, gambols at his feet. The youngster at the beginning of the clip is my dad’s nephew Robert Dudley “Sandy” Goodlett, who died April 26, 2021. Readers of The Last Resort may remember references to “Sweetpea” visiting the boys’ camp. At the end of the clip, you’ll see my dad’s nephew Davy Fallis, aka “Sluggo,” who died March 7, 2018. One of the letters that Pud wrote to Davy and his parents while at basic training in Texas is included in Appendix A of The Last Resort. During a Goodlett family reunion in 1984, I remember being emotionally walloped when one of the Fallises played some of their archival movie footage that, at the time, I had no idea existed. By that summer, my dad had been gone 17 years. Suddenly, on a small screen in a northern Kentucky hotel gathering space, there he was in an intimate, playful moment with my mother, shortly before they were married. I gasped, and then I sobbed. If they played more old footage of either of my parents that evening, I missed it. (That’s Davy Fallis again, chaperoning the scene.) In the following clip, that footage is preceded by images shot on their wedding day, December 27, 1947. Lawrenceburg natives may recognize several in the wedding party: Lin Morgan Mountjoy, Bobby Cole, George McWilliams Sr., George McWilliams Jr., Vincent Goodlett, Ann McWilliams, Mary Jane Ripy, Ann Dowling, and Madison Bowmer (of Louisville). In this era of cell phones and selfies and images and video shared instantly with the world, it may be hard to imagine what it means to me to have this rare video of my dad. I have only a few memories of him from my childhood. So seeing him move—his mannerisms and his interactions with others—makes him real. It confirms what others have told me in recent years about his sense of humor and how much fun he was to be around. And, of course, it confirms all that I missed by losing him at such a young age. I am deeply grateful to Vince Fallis for preserving the original 8mm reels for more than 70 years and to Bob for making the video more widely available. This Father’s Day, I am thinking about playful Pud, and I am having a good day. The only other video of Pud that I’m aware of was shared with me by Bob Cole, Bobby Cole’s son. Appropriately, my dad is fishing. You can watch it here.

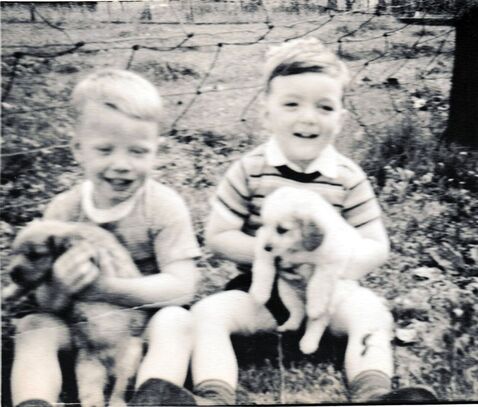

Philip on his new trail horse, October 2020. Philip on his new trail horse, October 2020. Philip Cullen was irrepressible. If he wasn’t racing, he was volunteering at a race. Or officiating. If he wasn’t focusing on triathlons, he was fooling around with trail running or Ride & Tie events—at least until an unfamiliar horse got the better of him last spring. So Maureen gave him his own horse when he retired this past fall so they could trail ride together. At triathlons, he usually attached a stuffed animal to the front of his bicycle just to give all the serious racers around him a laugh. He was good, and I imagine the sight of Philip passing with a stuffed tiger on his bike gave his competition motivation to pass him later. He didn’t care. He trained with discipline and he wanted to race well for the Irish National Team, but the focus was always on fun. What surprised me most about Philip was the volunteering he did. He always volunteered to work the polls on voting day. He volunteered at every area triathlon he did not participate in. He helped coordinate training tris. He led the Tri Club. In just the last six months, I know that he volunteered to get jabbed in the J&J COVID vaccine trial back in November; volunteered to help with traffic and statistics at COVID testing sites; volunteered with the Red Cross assessing flood damage to homes in Eastern Kentucky this spring; and volunteered at the Big Turtle race in Morehead, Ky., in April, where he had planned to complete a 50K trail run before those niggling chest pains caught his attention and finally sent him to the doctor the day before.  Philip's wife, Maureen, took this photo as he headed to his last day of work at Lexmark. Philip's wife, Maureen, took this photo as he headed to his last day of work at Lexmark. And, of course, it was only recently that Philip stopped working. He used to come out to our place after work, swim a mile and a half, have a beer, and then participate in a conference call with colleagues in the Philippines on my back patio before heading home. That’s when he didn’t have to be in China or Cebu handling business. Evenings when work wasn’t pressing, he might have a couple of beers and then start storytelling in his fading Irish brogue. I used to worry that his long stories might disturb the neighbors. But I expect they were laughing along with us. Philip had tales of killer kites in India or the heat in Singapore. His years at the rival engineering school in Louisville. His frequent trips back to Ireland and the family he discovered there. And we cannot forget his devotion to his family. He usually called me when he was on I-64 heading to Louisville to see his dad (and his mum before she died in 2018) or on I-75 to Ohio to see Maureen’s family. He was always there for them, whether helping address health issues or celebrating holidays or simply offering a helping hand. In short, his heart was bigger than most. It gleefully carried a bigger load than most. It worked at a superhuman pace for sixty full years. No wonder it needed a rest. Philip, you got more out of life than most of us ever dream of. You brought laughter and encouragement to the rest of us. You overcame injuries that might have beaten down a mere mortal. But nothing stopped you. You went full bore all the time. The lucky among us only get nine lives. You used up every last one of them. Rest in peace, my friend.  Sweetpea and Sluggo (Sandy Goodlett and Davy Fallis). Sweetpea and Sluggo (Sandy Goodlett and Davy Fallis). Only two children appear in The Last Resort, my dad’s 1943 Salt River journal: Sweetpea and Sluggo. The affectionate nicknames Pud had for his first two nephews tell you everything. In March 2018, I memorialized Sluggo, aka Dave Fallis, the elder son of my dad’s sister Virginia Fallis, when he died after a long illness. Today, I honor Sweetpea, aka Robert Dudley “Sandy” Goodlett, the first son of my dad’s brother Billy Goodlett, who died unexpectedly Monday after a brief illness. When David Hoefer, the co-editor of The Last Resort, suggested that we annotate many of the personal and historical references in the journal to provide a more fulsome picture of Pud’s world, I knew we had some work to do. David researched most of the historical and technical details. I started digging up information about Pud’s family circumstances and his Lawrenceburg friends. The first person I called was Sandy. He was the Goodlett family historian, and he had sustained ties to Lawrenceburg longer than the rest of us. David and I met with Sandy in his office in the building I still think of as the old post office, and we peppered him with questions. He was able to answer most of them, and I think he reveled in being a critical informant for our project. Soon I realized I wanted to make a trip to the Atlanta area to talk to a couple of the “boys” who used to join my dad at his Salt River camp: my cousin John Allen Moore and Lawrenceburg native Bill “Rinky” Routt. Sandy said, “Let’s go.” We picked a date and Sandy drove me and our cousin Bob Goodlett to Atlanta and back. During that trip, we were also fortunate to spend some time with John Allen’s younger brother, Joe Moore, and with Lawrenceburg natives Eugene Waterfill and Mary Dowling Byrne. It was a magical trip. And Sandy made it happen. Today, of all my dad's family and friends we visited, only Joe Moore survives. Sandy was always unselfish with his time and his wisdom. If I planned a family gathering, I knew he’d be there. In his van, we discovered we could talk for eight straight hours and still learn something new. When Sandy died, I lost not only a beloved cousin and my go-to guy for all Goodlett family questions. I lost one more connection to the father I never really knew. I’ve laughed this week with some family about Sandy’s rare equanimity and quietude in times of crisis and distress. That is not a typical Goodlett trait. Most of us are hard-headed and opinionated and high-tempered. We are intense and hard driving. Sandy kept his intelligence and his passion quietly under wraps. And when he offered us a glimpse, it was usually accompanied by that inimitable grin. If we want to honor Sandy, we should all strive to approach life’s vicissitudes with his calmness and acceptance. We should strive to be as kind and caring as he was. And we should strive to love our family half as much as he did. Read Sandy's obituary.

|

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed