Cover art by Stacia Brady, Ada Limón’s mother. Cover art by Stacia Brady, Ada Limón’s mother. Last week I had the privilege of hearing Kentucky resident and nationally-acclaimed poet Ada Limón read from her newest collection, The Carrying. Rich Copley, writing for the Lexington, Ky., Herald-Leader, said, “The book is colored by the deep green of Kentucky….Limón’s work is marked by exquisite, minute details that pass by many people.” It is indeed a lovely book, with heart-rending personal reflections and keen observations of the world that surrounds her. After the reading—during which Limón exhibited her usual warmth and quiet exuberance—an audience member asked why she wrote so frequently about nature. I wish I had been prepared to capture her full response, but my general recollection is that she writes about nature because she has to. It defines her place in this world. The first poem in the collection, “A Name,” reminded me of my father. When Eve walked among the animals and named them-- nightingale, red-shouldered hawk, fiddler crab, fallow deer-- I wonder if she ever wanted them to speak back, looked into their wide wonderful eyes and whispered, Name me, name me. At its most elemental, the journal my father kept at The Last Resort was a means for recording the natural world around him: the birds, the trees, the wildflowers, the river level, the snakes, the peepers calling in the spring. He documented the names of each, both the common names and the scientific names, as he prepared, wittingly or unwittingly, for a future career. He understood that in order to acknowledge the intricate parts of the natural environment, it was important to be able to identify each by its name. The name itself would then call up a fulsome list of traits and characteristics—some unique, some common with other similar species—that defined that particular plant or creature. If the critters could talk, I suspect there were moments when they indeed had a name for my dad: threat, intruder, murderer. He describes a memorable moment after he has shot a young squirrel: “I can still see that tiny baby sitting hunched on that limb, chattering gleefully to himself and gnawing on a pignut. To think that I would snuff out such a happy existence. It will never happen again.” Sadly, it took being hunted by his fellow man during World War II for Pud to finally end his hunting of animals for sport. Is there perhaps a more sinister consequence of naming others who share this world with us? When Eve named the things in the garden, did she innocently guarantee their ultimate destruction? Once they became separate from the two who claimed dominion over them, once they were identified as different, were they expendable? Insignificant? Unprotected? On the other hand, it’s hard to truly see what we can’t name. During our daily rush to and fro, we pass trees and wildflowers and songbirds. If we can’t name them, we don’t see or hear them. We don’t recognize them or respect their importance. If we don’t recognize their value, we don’t feel remorse when they are destroyed. We stand by and allow their annihilation without understanding what we have lost. Part of this journey for me, as I write about my father and the words he left behind, has been learning what it means to belong to the genus Goodlett. As my cousins and I gather more regularly to honor our long-gone parents, we ponder the mysteries of our Goodlett ancestors, and we try to figure out who we are. If our name is Goodlett, what does that mean? What are our traits and characteristics? Would a dichotomous key distinguish us from the Smiths and the Joneses? Does the name carry pre-packaged notions? How do others respond to it? How do I live up to it? Or carry its burdens? How has my name defined who I am, or my ultimate fate? In Limón’s poem, Eve’s plea to be named also feels like a voicing of her desire to be part of the community she is ordering. Perhaps a name would define her place, her role, her responsibilities among the others that share her space. Perhaps once we identify ourselves, we can see more clearly how we must defend and protect all the species that inhabit this earth. For more on the importance of naming things in The Last Resort, refer to David Hoefer's blog The Power to Name.

0 Comments

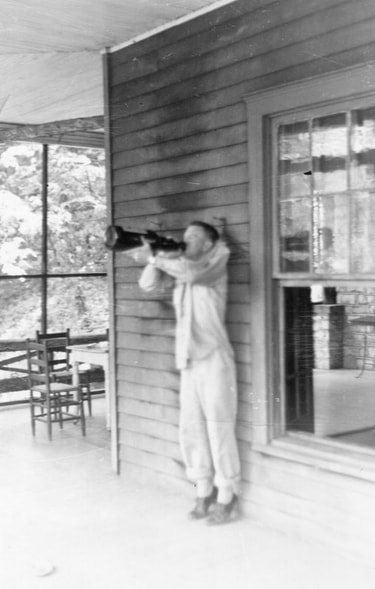

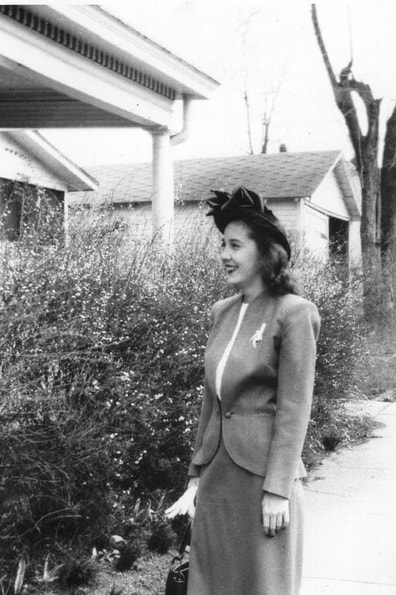

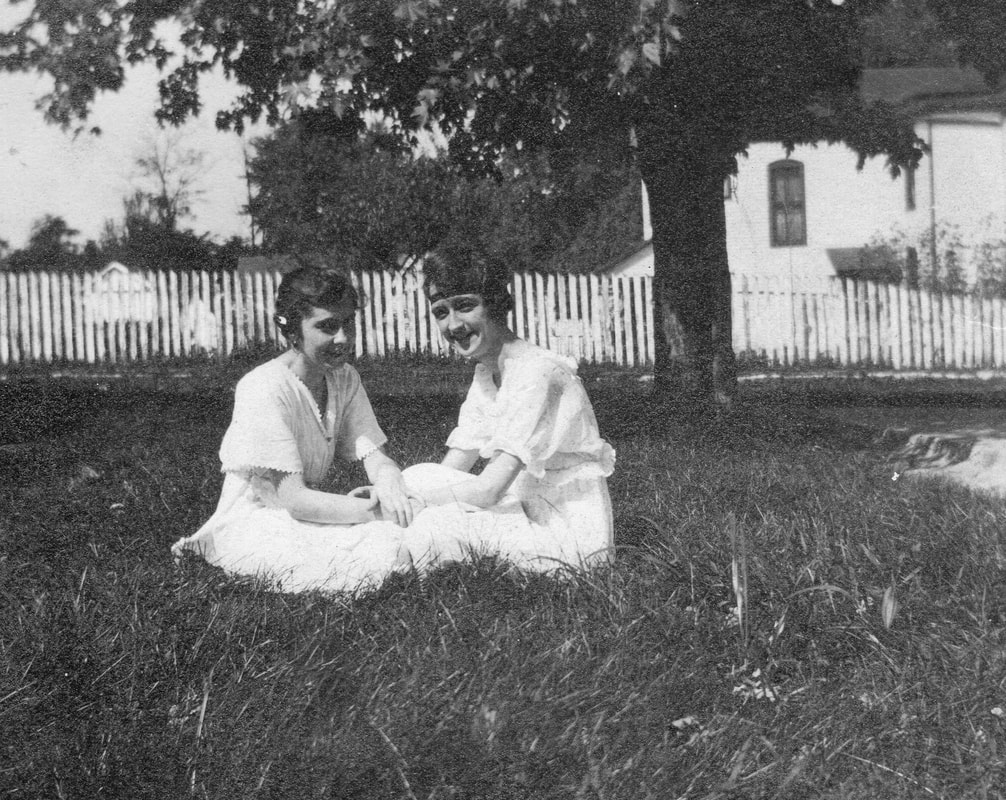

Could this be my grandfather, William Lyons Board (1892-1946)? Could this be my grandfather, William Lyons Board (1892-1946)? As I dug around in a box of old photos that appeared to be relics from my mother’s family, I stumbled across one I’m certain I had never seen before. It’s a photo of a man in a WWI Army uniform standing near a river, hand on hip, cigarette in hand, with a rakish grin on his face. Could it be? In January (Whispers from the Past) I wrote about my efforts to develop a distinctive voice for my maternal grandfather, who is at the heart of a novel I’ve been working on in fits and starts. In that blog, I indicated that I did not have a photo of him. Or did I? When I found the photo, I immediately flipped it over to see if there was a name scrawled on the back. What I found instead was another photo: a photo of two young women smiling broadly as they engaged in what appeared to be an intimate tête-à-tête, cross-legged on a well-maintained lawn. Judging by the dress, I put the date in the early 1900s. I was not certain that I recognized the women, who appeared to be in their late teens or early twenties. On a hunch, I sent the photo to my cousin Bob McWilliams. He immediately identified the woman on the right as his grandmother, Mary Marrs McWilliams, born in 1894. In my mind, I then felt fairly certain that the woman on the left was her older sister, my grandmother, Nell Marrs Board, born in 1890. (I give both women’s married names, but I doubt either was married at the time of this photo.) I searched and eventually found other photos of Nell from that general era and now feel certain she is indeed the young lady on the left. My heart started pounding. Had I finally found a photo of Nell’s scoundrel husband, William Lyons Board, the man who abandoned Nell and her infant daughter, my mother, shortly after the baby was born? (Contrarily, had Nell’s family run him off for some reason? Had they forbidden her to keep any photos of him?) Had Nell glued the smaller photo of Lyons to the back of this innocent photo of her and her sister, so she could keep some small memento of him? If it is indeed Lyons, is the river the Ohio River near where he trained at Camp Zachary Taylor south of Louisville before being shipped off to France? Or might it be a site near Le Havre or Cherbourg, two French cities he passed through en route to the limited action he saw? Is it the Isle River, which runs through West Perigueux, where he trained in September 1918? Or the Cher River on the outskirts of Saint-Aignan, where Lyons’ unit joined the 1st Depot Division and were later redeployed as replacements for combat divisions at the front? At the moment, I have no way of knowing. My good friend Chuck Camp, who has devoted a massive number of hours to researching this mystery, summarized his conclusions this way: “So [Nell] had this picture of her beloved sister, and hidden behind it is a picture of the man she married. She couldn't bear to throw it away, as she had so many others. But she couldn't bear to have it out all the time, either, so she hid it. “How poignant, how romantic, how sad. Here he is in his uniform, as he was in 1918, the dashing young man who came home from the war and swept her off her feet. And now, 100 years later, his little girl's little girl has found him and brought him home again.”  Pud goofing around at Johnson's Camp, summer 1947. Pud goofing around at Johnson's Camp, summer 1947. “When I think of Pud, I think, ‘Here comes fun!’” That’s how Diana Mountjoy Hill responded in 2015 when I asked her about any memories she might have of my father. I had just started working on The Last Resort, and I was trying to track down anyone I thought might be able to offer me insights into his life in Lawrenceburg. Bill Bryant, a Lawrenceburg native and retired professor of biology who had written an article about my father’s academic career—which included the statement “Common sense, and a sense of humor, were essentials for John Goodlett”—pointed me to Diana, whom I had always known as “Dyna.” Pud and her dad, Lin Morgan Mountjoy, were great friends. The Mountjoy family had a big farm between Lawrenceburg and Pud’s camp on U.S. 62, so I have to imagine Pud stopped by there frequently on his way to or from Salt River, occasionally entreating his buddy to join him for some fishing. And I know Lin Morgan and his wife, Joy, visited the camp after the war with Pud and Mary Marrs.  Lin Morgan Mountjoy. Photo provided by Diana Mountjoy Hill. Lin Morgan Mountjoy. Photo provided by Diana Mountjoy Hill. Like nearly all of Pud’s buddies, Lin Morgan also served during WWII. Diana tells me that he and Joy wrote each other every day while he was in training at Deming Air Base in New Mexico and later while serving in North Africa at a base near Casablanca. When they all somewhat miraculously made it back safely to Lawrenceburg, Lin Morgan was in Pud and Mary Marrs’ wedding in December 1947. Diana was born to Lin Morgan and Joy a couple of years after that. So she was still pretty young when Pud would stop by the Mountjoy farm on his rare visits home from the Northeast. “Whenever I heard Pud’s Ford convertible careening down our long driveway, I would run to the front window,” continued Diana. “I knew all hell was about to break loose.” I can’t think of a better legacy than to be forever associated with “fun.” When I first heard this anecdote, I admit I was surprised. Others had shared stories about my dad’s sense of humor and his ability to talk easily with anyone from any circumstances. I had heard him described as “folksy.” But none of this initially jibed with my recollection of a disciplinarian and a serious academic. I’ve been delighted, however, to embrace this image of the man I never really knew. Sometimes, when I choose going outside to play rather than spending another hour inside taking care of work, I think of him. When I’m spending time with friends and I see myself fall into playful behavior unbefitting a woman d’un certain âge, I think of him. When I jump in the lake for a swim or paddle my boat to a back cove in search of turtles or Great Blue Heron, I think of him. My cousin Vince, Pud’s nephew and namesake (“John Vincent,” named for his uncle John Campbell [Pud] and his uncle Robert Vincent, the youngest and oldest Goodlett brothers), told me, “He was a cool dude. He just seemed relaxed and easygoing.” I’m not sure those are shoes I can fill, but a legacy of “fun” is one I’d be proud to continue.  Mary Marrs Board in Lawrenceburg in April 1947, shortly before she married Pud Goodlett. Mary Marrs Board in Lawrenceburg in April 1947, shortly before she married Pud Goodlett. Tim Cooper of Oakdale, Minn., responds to the recent post Whistling Past the Graveyard. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. T. S. Eliot once wrote, “Great works of art always mean more than they are capable of expressing.” Whenever I return to Pud Goodlett’s journals in The Last Resort and reread his thoughts as a young man, I am reminded of Eliot’s quote, of how even something as apparently straightforward and unencumbered as a camp logbook can resonate with unexpected intent and purpose. I am particularly cognizant of Goodlett’s love of place and family, and how scholarly success never weakened his ties to Kentucky. When I read Sallie Showalter’s recent blog—which mirrors this attachment to family and place—I realized there must be a mystical connection between people and location that sometimes transcends all else. As I was growing up, my family moved a dozen times to a dozen different states while my parents pursued graduate degrees and visiting professorships. I learned early not to form an attachment to a place. I am also the only child of an only child, and I can count my remaining relatives on one hand. I am watching my mother die from Parkinson’s disease. So I use the term “mystical” deliberately when thinking of those who experience this ineffable pull of family and place. As a young man, I was unaware of its power. As I contemplate the latter phases of my life, as I extricate myself from the shackles of my career, I yearn for those ties to a constant place and to people who knew me way back when. That, in a roundabout way, brings me to Pud’s wife, Mary Marrs, and my brief encounters with her when I was young. I recall her as a woman of unassailable beauty and grace. She, too, served her country during WWII by leaving her small-town home in central Kentucky and going to work for the Navy in Hawaii. (A tough gig, that.) Like many of the more fortunate members of her generation, she returned to her roots when the conflict concluded.  Mary Marrs around the time Tim Cooper met her. Mary Marrs around the time Tim Cooper met her. I must have been 15 years old, a friend of her older daughter, when I met her. She always treated me with the utmost kindness. One story will suffice: I’m not sure where her two daughters were, but she and I found ourselves in her kitchen, drinking coffee early one morning. We must have talked for an hour, and while I don’t remember the thread of our conversation, I do recall that she took me—a 15-year-old boy and all that that entails—seriously. I also recall her discussing her deceased husband and telling me how I would have liked him. It was only years later, after the death of my own father at an absurdly young age, that I recognized in the eyes of my mother the look on Mrs. Goodlett’s face during that talk: a look of bereavement, confusion, controlled anger, and a sadness that cannot be articulated. And just as Mary Marrs had returned to Lawrenceburg from her home in Maryland after Dr. Goodlett’s passing, so my own mother left Kentucky and returned to her family in Minnesota after my father’s death. The pull of place, of family, of familiarity surmounted the grip of artificial roots. And while we could argue whether these two women made the right decision, who can argue with the gravitational pull that lured them home? Camus wrote: “There are places where the mind dies so that a truth which is its very denial can be born.” The human condition is absurd: we plan, we strive, we rely on rational, systematic thought to live. And yet, our mortality tells us that our existence is provisional and transitory; it is irrational. We carve out careers, and they crumble into insignificance when we visit the gravesites of our relatives; we remember our deceased loved ones in their vibrant youth, and yet we somehow live longer than they; we live in exciting locales among interesting friends, and yet our profound meaning comes from our place of origin. It is, indeed, when we delve into and accept the irrational—the “dying of the mind”—that we find our true selves, our “truth.” And for those, like me, who do not have roots, who do not have a family or place which circles the wagons and protects us, this irrational absurdity compels us to act, to rebel, to define ourselves by our actions, by our choices. Pud Goodlett, writing home about what he witnessed at the Nuremburg war crimes trials, wonders if his brother Vincent, an attorney who had served his country in England, would have found the events interesting. And his widow, talking about her deceased husband to a teen-age boy as though this untamed youth were the most important person she had ever met, perhaps unwittingly reveals the most profound truth she knows: family and place are what bind us to this earth, and to each other. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed