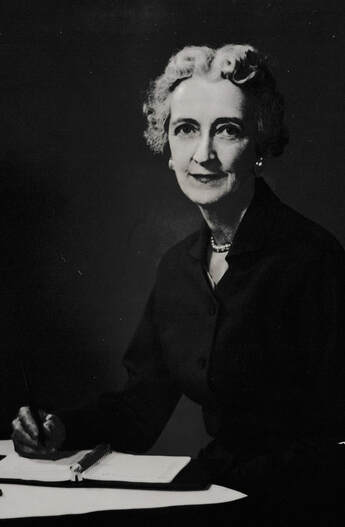

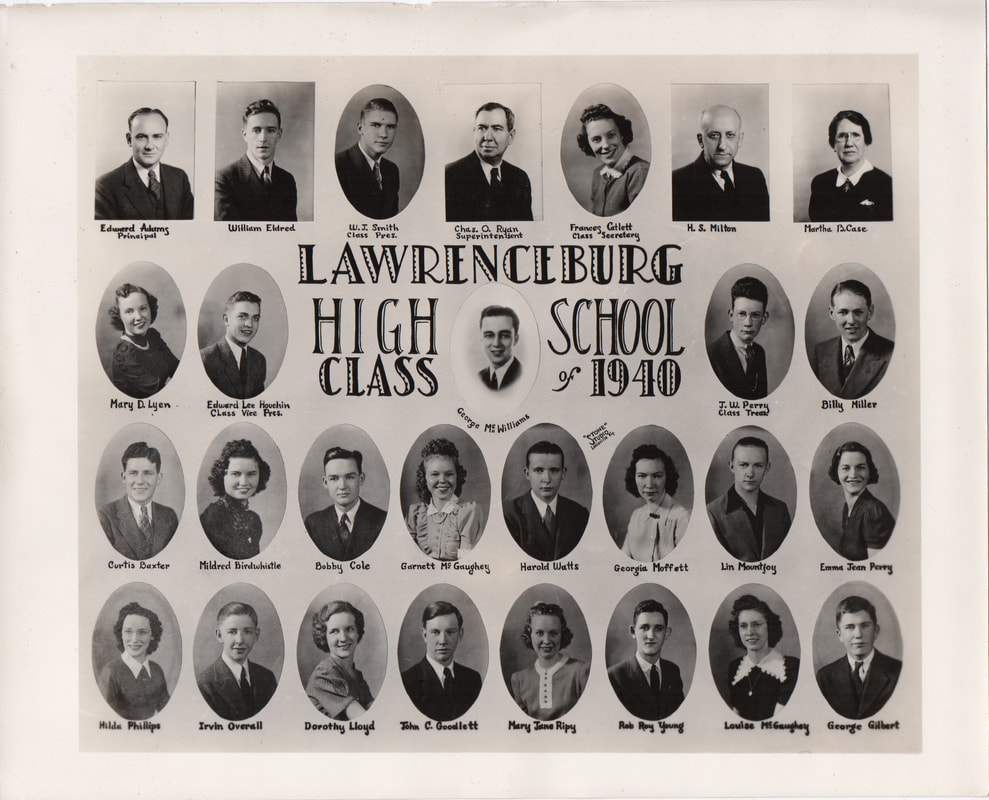

Mary Louisa Marrs McWilliams (1894-1977). Photo provided by Bob McWilliams. Mary Louisa Marrs McWilliams (1894-1977). Photo provided by Bob McWilliams. After my great-aunt Mary McWilliams suffered her final stroke, she was lying in a hospital bed, largely unresponsive. I approached her bedside with some trepidation. I was 17. I had something important to tell her. “Mamaw,” I said, “I’ve decided to go to Centre College.” She smiled. She did not respond verbally. She did not open her eyes. But she heard me, and she was pleased that I had finally decided to follow her to her alma mater. At the time, I wasn’t particularly happy about that decision. I had wanted to go far, far away from Kentucky, far away from Lawrenceburg. I had never quite found my footing in my parents’ hometown after being dislocated from Baltimore shortly after my father died. I was still largely alien to my classmates. But I was set to graduate from Anderson County High School in a couple of months, and I had finally accepted my mother’s arguments for going to a school 30 miles away rather than one hundreds of miles away. Knowing that Mamaw approved made the choice a little more palatable. I was happy that I had shared some news in her final days that made her happy. It sometimes seems ironic to me now that I am spending so much time digging into my ancestors’ stories and learning about Lawrenceburg’s history. I had hoped I had gotten away for good when I went on to graduate school in North Carolina. But I unexpectedly ended up back in Kentucky, and somehow I have never left. So now I am looking forward to joining over 30 other authors at the Anderson Public Library’s First Annual Book Fest on Saturday, October 19. It feels a bit like a homecoming. As I’ve traveled to various communities in the last two years sharing the story of Pud and Bobby down on Salt River, I’ve begun to feel pride in my Anderson County roots. Under my cousin Sandy Goodlett’s patient tutelage, I’ve learned how widespread my ties to the county are. It seems appropriate that this event will be at the beautiful, recently renovated Anderson Public Library. Adjacent to the library’s front door is a portrait of Ann McWilliams, Mary McWilliams’ daughter-in-law, who dedicated a decades-long career to improving the viability of that local institution and making it a proud testament to the community’s curiosity and love of reading. Mary McWilliams’ sister, Nell—my grandmother—worked at the old Carnegie library on Woodford Street, which is now the Anderson County Tourism Office and History Museum. Growing up, I spent many hours in both buildings. My mother made sure of that. For me, the library was always a welcoming place that offered spellbinding riches: all the books you could read. For free. Now, of course, libraries offer so much more. I hope you’ll make plans to stop by Saturday, October 19, between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m. and say hello. It’s an honor to be there to represent the story of an Anderson County native and chat with my Anderson County family.

2 Comments

Along the trail at Bernheim Forest. Along the trail at Bernheim Forest. Joe Ford of Louisville offered these thoughts after reading the post “Home on the Ridge,” which ponders whether an affinity for the outdoors can be inherited. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. When we were young, weather permitting, my parents would stuff all eight of us children into the car and head south out of Louisville to Bernheim Forest. Once there, the doors flung open and we loudly poured out. Save for a couple of ponds where you could feed the (kind of scary, tall as us) Canada Geese with a fistful of corn from a converted gum ball machine, there wasn’t much there except the miles of expansive woods, rocky streams full of crawdads (“Oh sister, I have a surprise for you!”), and a few picnic areas good for frisbee and football. Perfect. And almost deserted. Toward evening, the deer would steal into the meadows and we fell silent and talked in whispers. At times, though, we drove right past the entrance to Bernheim, continuing west then south down SR 245 to Bardstown, past the Cathedral, south across the bridge at Beech Fork and left at the tiny sign that simply read “Trappist.” Once inside the stone walls that flanked the parking lot for the Abbey of Gethsemani, we knew to keep our voices hushed and our steps measured. No one told us. It was just the nature of the place. My Dad would slip inside the gate house and let the brothers know we were there. We’d drive or walk across the fields to the edge of their woods and haul our picnic fixings up to a few tables scattered among the trees. We were popular picnic company, as we came bearing fried chicken and beer—neither a normal item on the monks' menu. (I know I don’t need to say this to the readers of this blog, but just in case it somehow falls into the wrong hands… You cannot just show up and invite the monks out for a couple of cold brewskies and fried chicken. My father taught them philosophy and maintained ongoing friendships with many of them. You have to bring St. Thomas, too.) Afterwards, we would walk the woods and then attend vespers or compline before heading back home, a quieting and sacramental end to the day. In later years I’d walk those woods again, a little more cognizant of “the nature of the place.” But what stayed with me was the sense that every wood, every meadow at evening, was imbued with meaning, with beauty, was sacramental. That is, whether considering the joy of Bernheim or the sense of the sacred at Gethsemani, in my young mind they mixed; woods were woods, and woods were sacred. Why do we have such a sense of awe for nature, such reverence? Think of all the cultures that consider the woods or the mountains either sacred in themselves or as the dwelling place of gods. The Incas in South America. The Sherpas in Nepal. Where in our brain—or should I say soul—is that, and why? Of what evolutionary advantage is that? Or, purely from an aesthetics point of view, why do we think they are beautiful? Why are they pleasing to us? I’d like to think it is the little bit of divinity in each of us that connects with nature's sublime beauty. We recognize and respond to the Creator's presence there amid the mountains and the trees and the gurgling streams. It’s why we say we feel at home. "Home on the Ridge" ended with a quote from Henry David Thoreau. I will take that as permission to end this with a rather long quote from a resident of the abbey itself. I’ve loved this passage for years, but only noticed just now how much Merton recognizes the echoes of the divine in nature. "The Lord plays and diverts Himself in the garden of His creation…,We do not have to go very far to catch echoes of that game, and of that dancing. When we are alone on a starlit night; when by chance we see the migrating birds in autumn descending on a grove of junipers to rest and eat; when we see children in a moment when they are really children; when we know love in our own hearts; or when, like the Japanese poet Bashō we hear an old frog land in a quiet pond with a solitary splash—at such times the awakening, the turning inside out of all values, the “newness,” the emptiness and the purity of vision that make themselves evident, provide a glimpse of the cosmic dance… "No despair of ours can alter the reality of things; or stain the joy of the cosmic dance which is always there. Indeed, we are in the midst of it, and it is in the midst of us, for it beats in our very blood, whether we want it to or not. "Yet the fact remains that we are invited to forget ourselves on purpose, cast our awful solemnity to the winds and join in the general dance." —Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation  Salt River near Shepherdsville, Ky. Photo credit: https://www.facebook.com/awesomelazyriver/ Salt River near Shepherdsville, Ky. Photo credit: https://www.facebook.com/awesomelazyriver/ David Hoefer, co-editor of The Last Resort, shares a contemporary view of Kentucky’s Salt River. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Recently, while driving south on I-65 from my home in Louisville, I reached the point where Salt River passes underneath the interstate near Shepherdsville. From here the river flows west toward its confluence with the Ohio River at West Point. What I saw that day was very similar to what appears in the accompanying photo. The river bloomed with colorful innertubes whose passengers were basking in the glow of sunshine and (who knows) maybe an occasional adult beverage or two. I had a good laugh, because I’ve trained myself to think of Salt River as Pud’s private Arcadian getaway. But other people have other ideas about possible uses for this natural resource. Awesome Lazy River evidently sponsors these Salt River floats most summer weekends, creating a motley human carnival on the river. It’s a far cry from the mid-century black-and-white images of intrepid fishermen in waders standing in the shallow riffles near Camp Last Resort. Indeed, the American entrepreneurial spirit is something to admire. As I continued traveling south, I pondered the paradox, remembering that even Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond was within walking distance of an already substantial civilization. It appears that we humans continue to find respite in nature, especially when the comforts of society are close at hand. A few months after my father died, after we had moved from Baltimore and settled in our new home in Kentucky, I woke up late one evening in a panic. I thought I was going to die. I was certain of it. I don’t remember if I had a sensation that my heart was failing me, or if I just had a sense of dread. I was eight years old. I remember sitting with my mother on her bed as she called the doctor. I don’t recall if I was crying. I expect I was frightened. I know my mother must have felt a sense of panic and helplessness. Thankfully, our doctor at the time, George Gilbert, was not only a small-town doctor (who later made regular house calls to soothe my troublesome earaches with shots of penicillin), he had also been a classmate of my father’s. He had known both my parents well. After briefly explaining the situation to him, my mother handed the phone to me. I listened as he tried to reassure me that everything was OK. I don’t think I believed him. But I understood even then that death was inevitable, and if it was my time, it was my time. This long-repressed scene played out again in my mind as I heard details of the Inspector General’s report relating to the harm done to small children who were separated from their parents upon arriving at our southern border. One child reported, “I can’t feel my heart.” Another said, “every heartbeat hurts.” These were explained as physical manifestations of the emotional pain the separation had caused the children. One story in particular stuck with me. “A 7- or 8-year-old boy was separated from his father, without any explanation as to why the separation occurred. The child was under the delusion that his father had been killed and believed that he would also be killed. This child ultimately required emergency psychiatric care to address his mental health distress.” I suppose it makes sense that young children who identify with their parents might expect that their parent’s fate could be their own. If parents can’t protect themselves from some harm—arrest, separation, death—how can they protect their children from these same terrors? I am still amazed when I wake up each morning. I have always expected to share my father’s fate. But I’m old now. I’ve outlived him by 16 years. I did not succumb prematurely. Nonetheless, this is a tiny trauma I have carried throughout my life as a result of losing a parent unexpectedly at a young age—at the same age as the boy separated from his dad. Yet I knew what happened to my father. I had a loving mother who cared for me in a secure home. I cannot imagine the lifelong repercussions and insecurities this young boy might face. For me, this is a reminder that all this country is doing in the name of “policy” is personal. Our separating families at the border affects all of us. Our denying climate change and rolling back common-sense regulations affects all of us. Our refusal to restrict widespread access to military-style weapons affects all of us. We will feel the pain of the Central American refugees, the residents of low-lying coastal communities, and the families who have had loved ones slaughtered. We all share common humanity. We all respond to loss and fear the same way. I had promised that I would not revisit my “father loss” theme again so soon, but circumstances keep pushing me back to that well. If that early experience is what connects me to the world at large, then its value—and its pain—is a privilege that I need to share. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed