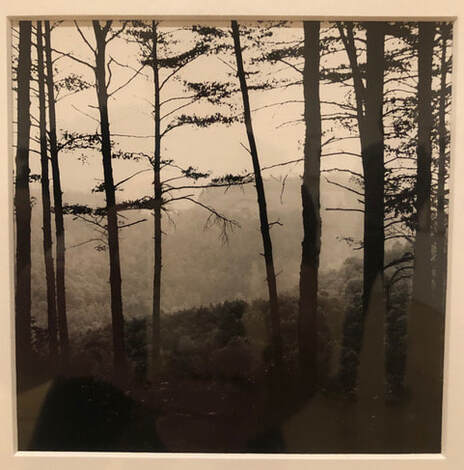

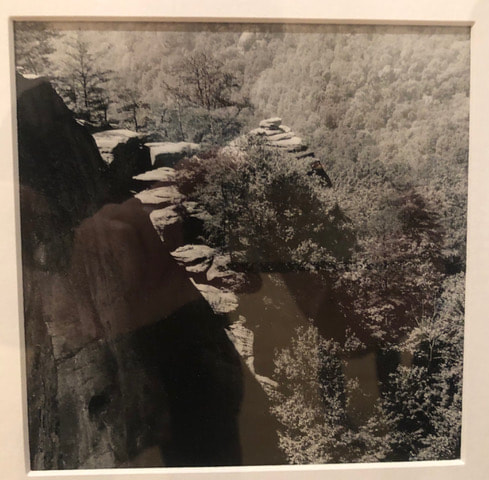

Photograph by Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925–1972) from “The Unforeseen Wilderness,” 1967–1971, as currently exhibited at the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Ky. ©The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Images of exhibited artwork captured by David Hoefer. Photograph by Ralph Eugene Meatyard (1925–1972) from “The Unforeseen Wilderness,” 1967–1971, as currently exhibited at the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Ky. ©The Estate of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Images of exhibited artwork captured by David Hoefer. David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, reminds us of the power of art. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw the emergence of environmentalism as a significant element in the political wrangling of the day. Kentucky old-timers likely remember one of the pivotal episodes in that emergence: the battle over damming the Red River and what would have been the wholesale alterations to landscape and ecology resulting from infrastructure of that magnitude. The Army Corp of Engineers and many local residents lined up on one side; the Sierra Club, environmentalists, and various culture warriors lined up on the other. Each alliance had serious points in its favor. Ultimately, with the scrapping of construction plans, the environmentalists won out. The gorge is now protected by inclusion in federal programs for natural, historic, and archaeological settings. I bring this up because the J. B. Speed Art Museum in Louisville is currently hosting an exhibit that was directly inspired by the battle over Red River Gorge. One of the dam’s chief opponents was Kentucky author Wendell Berry. Berry coauthored a book, The Unforeseen Wilderness, with another native artist, the Lexington photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard. It is Meatyard’s photographs from this collaboration that are on display, and which allow us to reenter that time and place in history. The Unforeseen Wilderness is undoubtedly the most important document for the defense of the ecological and spiritual qualities of a unique landscape to emerge from the conflict. (I suppose the other side could point to the dam’s architectural plans and, no, I’m not being facetious. Good engineering is to be admired.) Meatyard and Berry worked separately and together to produce their dual vision for preserving the gorge. Berry uses words, so he carries the weight of argument, which is sometimes cranky and polemical. Meatyard uses shadow and light, which means that he comes closer to presenting the gorge as it is, or was, within the limitations of photographic technology and one man’s subjective response to the world in front of him. The great variety of settings at Red River, the many microclimates and eco-niches, becomes immediately apparent in Meatyard’s camerawork, which is amply attested to in the book and the exhibit. That diversity bounding on the infinite may be the best case for leaving the flood-prone gorge in its (more or less) natural state. My wife and I noted the darkness of many of the photographs. Some of this was attributable to museum lighting, but the darkness was also a conscious decision by the artist, either in camera settings or darkroom procedure (or both). Berry addresses this facet of Meatyard’s work in his foreword to a revised and expanded edition of The Unforeseen Wilderness, published after the photographer’s death from cancer: “As I look now at [Meatyard’s] Red River photographs, I am impressed as never before by their darkness. In some of the pictures this darkness is conventional enough. It is shadow thrown by light; we see the lighted tree or stone and we see its cast shadow. In other pictures the darkness is not shadow at all. It is the darkness that precedes light and somehow includes it; it is the darkness of elemental mystery, the original condition in which light occurs…The darkness of these pictures is an imagined darkness; and this was a courageous imagining, for the darkness is made absolute in order to make visible the smallest lights, the least shinings and reflections. Sometimes the lights require hard looking to be seen” (1991:xi-xii). Here we’re edging into the metaphysical. Maybe Meatyard’s Red River Gorge is more art than nature after all. The Meatyard exhibit is showing at the Speed until February 13, 2022. I’ve included a few photographs of the photographs as enticement. (Just think about how much better the originals will be in person.) Click here for more information on this intriguing backward look to the early days of the environmental wars.

4 Comments

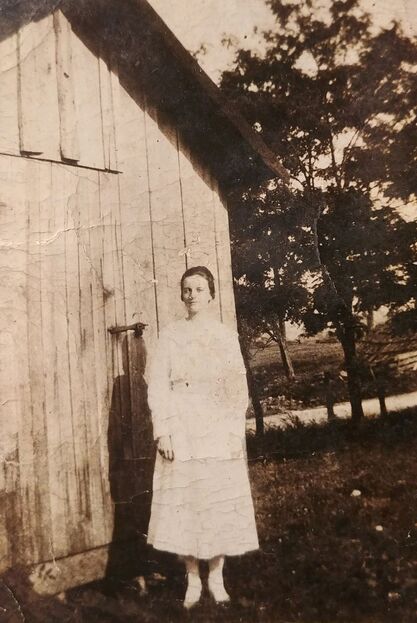

Allie Dudley Dawson, age 16. Photo provided by Jane Allen McKinney. Allie Dudley Dawson, age 16. Photo provided by Jane Allen McKinney. He carried this photo of Allie with him every day he was deployed to France during the Great War. Only sixteen, she was already lovely and as unbowed as the boards of the outbuilding behind her. Soon after he returned in the spring of 1919, he married her. She was just seventeen. He had first met her shortly after her birth. He was twelve when his father, a highly respected country preacher, walked him across the road to the neighbors’ farm to welcome the new baby. Their fate was already set. He must have watched her grow up, keeping a keen eye on her. At some point, while he waited, he left the farm where he had been raised with his five siblings and went to work as a telegraph operator in other Kentucky communities—Owensboro and Maysville—some distance from his homestead in Anderson County. Perhaps it was that experience that landed him in the Headquarters Company of the 338th Infantry when he was drafted in 1918. And perhaps that kept him just removed from the front lines that bloody fall as the infantrymen in his unit replaced exhausted or fallen fighters.  John Foster Moore. John Foster Moore. After their marriage, he settled in with his wife’s family on their farm, already so familiar to him, and worked again as a telegraph operator. Her five younger siblings made the household a lively one. In time, he took a job with the railroad in Louisville, moving his bride far from her family. When the Great Depression took its toll, he accepted a job that sent him to Atlanta, where the young family made their home until he died in 1966, and she followed in 1996. He was my grandmother’s younger brother, John Foster Moore. The couple’s oldest surviving son, John Allen, was one of my dad’s best friends. Their daughter, Jane, died May 26 at age 98, leaving only their youngest son, Joseph Perry, who still resides in Atlanta. All of John and Allie’s children were born storytellers, with family facts and lore at the ready, awaiting a simple prompt from an interested party. Their lives spanned a family’s generations. They knew my father, and they knew his grandfather. I never knew either. The memories they shared are priceless. As those in my generation continue to sort through the detritus of our parents’ lives, as we downsize and try to organize what will be handed down to the next generation (where there is one), we must preserve these photographic gems. They reveal who we are, where we came from, what mattered. They reveal the love that held a family together. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed