John Allen Moore, seated on the running board of Thomas (the Model T). Bobby Cole is behind the wheel. John Allen Moore, seated on the running board of Thomas (the Model T). Bobby Cole is behind the wheel. One of the regular visitors to The Last Resort was John Allen Moore, Pud’s first cousin whose family had moved to Atlanta during the Depression when his dad was offered a new job with the railroad. Although John Allen was three years younger than Pud, the two were close. In 1933, when the boys were 11 and 8, Pud traveled with John Allen and his parents to the World’s Fair in Chicago to celebrate a Century of Progress. While there they stayed with another cousin, Will Maurer, who was a chiropractor in the city. It’s clear from Pud’s journal that he was always pleased to have John Allen’s company at the camp. On May 31, 1942, soon after John Allen arrived in Kentucky for a summer visit, Pud describes the two of them having a “sleepless and reminiscent spell, not going to sleep until 2:00 [a.m.].” About a week later, there’s another entry: “John Allen and I went swimming in the Camp Hole and had a swell time riding the current, which must have been running about eight miles an hour.” At Christmas time, John Allen was back in Kentucky with his family. On Dec. 24, 1942, Pud writes: “Scoured the countryside with John Allen in search of a Christmas tree. Saw only two rabbits, but lots of birds.” When I chatted with John Allen about this book project, he would frequently recall the terrifying lightning strike that hit the cabin in June 1942. Pud described the scene: “A bolt of lightning ripped through the partly opened door between John Allen and me and crashed like a giant cracker. John Allen tried to wrap his legs and arms around his head…” Both men survived service in the infantry during World War II and both married a few years after they returned. Pud was John Allen’s best man in 1951. Their friendship endured until my father’s life was cut short. John Allen once described meeting the train that carried my father’s remains when it arrived in Kentucky in April 1967. He had not shaken the shock of my father’s untimely death. When he described the scene to me in 2015, I felt fairly certain that he still hadn’t fully recovered. On April 25, 2018, John Allen passed away after a long and eventful life. I am so grateful for all the stories he shared. I have to imagine that throughout his life he was the kind and gentle man I came to know. His ability to recall names and dates and details of our family history going back generations, even into his 90s, never ceased to amaze me. To John Allen’s wife, Jane Chappell, to his sister, Jane McKinney, and his brother, Joe, to his children and his grandchildren, I offer my sincere condolences. I want to honor him as my father would have honored him. In my imagination, the two are now hip deep in a flowing river, fishing rods in their hands. Bobby Cole, Joe Goodlette, and George McWilliams are probably nearby. Rest in peace all.

4 Comments

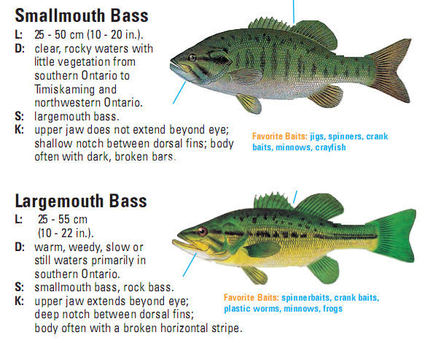

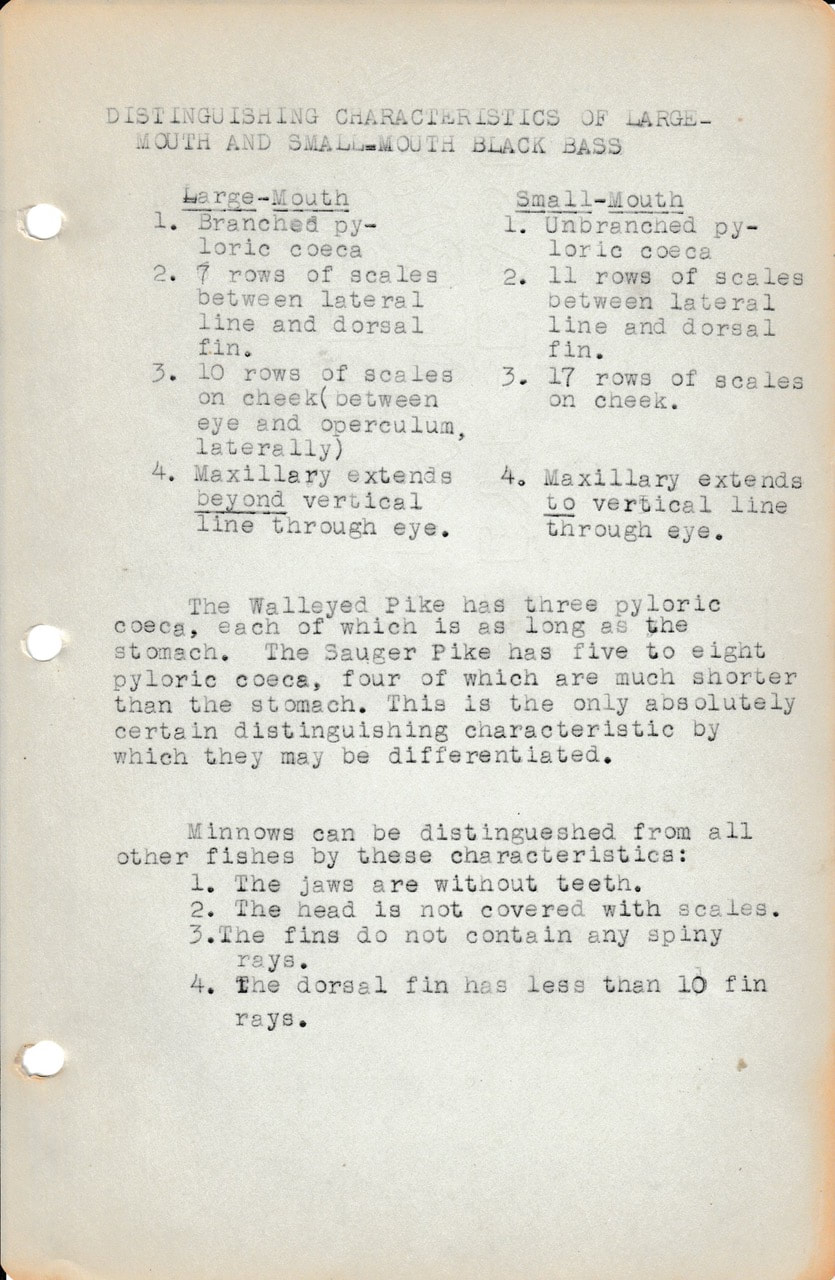

I’ve recently come to understand that writing is simply a series of decisions. We all have the essential vocabulary and familiarity with English syntax necessary to put words on a page. But every word, every phrase, every metaphor, every construction is a choice. If you’re writing fiction, every setting, every plot complication, every character’s reaction, every character’s character is likewise a choice. If I had understood this earlier, I sincerely doubt I would have launched so heedlessly into this vocation. I am typically paralyzed by decision making. When I was in college, I took a class called Cognitive Processes. I was fascinated by psychology and it was taught by one of my favorite screwball professors. Early in the semester I recall discussing how many decisions, large and small, we make each day. For a short period thereafter I froze as I stood in the cafeteria line trying to select something for breakfast. I had never before thought of that simple task as a series of decisions. Daily existence became almost unbearably cumbersome. For the writer, even if you survive the thousands of decisions necessary to complete an essay or short story or, heaven forbid, a novel, you are then faced with hundreds more related to marketing the work. During my checkered career, I learned that marketing has at least one thing in common with teaching: you can always do more. You can always be more imaginative, do more research, connect with more people, prepare more thoroughly. It’s open-ended. You are limited only by resources and time. Mostly time. Unless you are slavish to a data-driven method, marketing usually results in some hits and some misses. You make the best choices you can given what you know and the time you have to invest. It’s always a bit of a crapshoot. And that can make it particularly rewarding when some of the choices you make result in real opportunities to get the word out about a favorite project. On Saturday, April 28, I will have the privilege of participating in the Local Author Showcase celebrating Independent Bookstore Day at Lexington’s oldest—and largest—independent bookstore: Joseph-Beth Booksellers. Anyone who has spent time in central Kentucky in the past 25 years is familiar with the multi-level wonderland that is Joseph-Beth. It has been a key local source for books and gifts for two generations of readers. It’s one of the places that defines Lexington as a city that embraces literary artists, reading, and the life of the imagination. If you have a chance to stop by Saturday between 4 and 6 p.m., I would love to chat with you about The Last Resort or anything else on your mind. While you’re there, pick up something special for yourself or a gift for someone else. We can choose to support our local independent booksellers just as we choose the first words that open a story.  Image courtesy of www.fishingfury.com. Click the image for more information. Image courtesy of www.fishingfury.com. Click the image for more information. David Hoefer, of Louisville, Ky., is co-editor of The Last Resort and the author of the book's Introduction. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Much of the pleasure of reading The Last Resort journal lies in John Goodlett’s casual recording of a day’s adventures in a style that reflects the camp's relaxed atmosphere. We shouldn’t forget, however, that Pud had a second reason for writing: to try on for size the classroom instruction he was receiving in biology as an undergraduate at the University of Kentucky. Many of his observations involve the identification of plants and animals that were part of the natural wealth of Anderson County. In other words, the power to name, deployed with rigor and care. Of course, the boys of The Last Resort already possessed a vocabulary in the hundreds for local flora and fauna. But Pud was learning a new precision in naming based on scientifically defined relationships of plants and animals. The criteria for choosing one name over another is built into these schemes, typically as the presence or absence of one or more physical attributes. This branch of science, called taxonomy or systematics, is a refined form of pattern recognition. The difficulty Sallie and I faced in assembling The Last Resort’s taxonomic list was trying to link the variably deployed common names—sometimes called folk taxonomy—to the scientific equivalents of greater precision. Linguists have long noted that folk taxonomy favors family or genus over species. We comment on sparrows picking up crumbs off the sidewalk rather than House Sparrows (Passer domesticus). The existence of slangy terms adds further complication because slang comes and goes and can vary in meaning by region. I was surprised to find out that the redbellies caught by Bobby Cole in Salt River were Pumpkinseeds, a kind of sunfish (Lepomis gibbosus). In other places, a redbelly is a Redbreast Sunfish (Lepomis auritus). Does this mean that folk terms—those common names we all use, including scientists—are in some sense faulty and to be avoided? Definitely not. Popular terms do what they’re supposed to do: provide a robust, if flexible, basis for everyday communication, at exactly the level of precision required. Scientific classification sometimes goes too far in the opposite direction, pushing distinctions based on trivial differences and filing away our easy observations of nature (and nature’s beauty) in dusty cabinets of the mind. That said, it’s heartening to see Pud’s dedication to correctly identifying the living things around him. One senses the importance he placed on proper naming and, behind that, the joy he experienced in honestly acquired knowledge. Sure, The Last Resort journal was meant as a record of the daily doings of Pud and his pals in their Salt River haven. But the journal had another purpose all along: to help young John Goodlett build a bridge to his future, which he had already glimpsed in excellent new words for identifying the marvels of his daily acquaintance. In the photos above, David Hoefer displays a Smallmouth Bass (left) and a Largemouth Bass (right) pulled from Lake Cumberland in south central Kentucky. For a comprehensive database of fish species, click here.

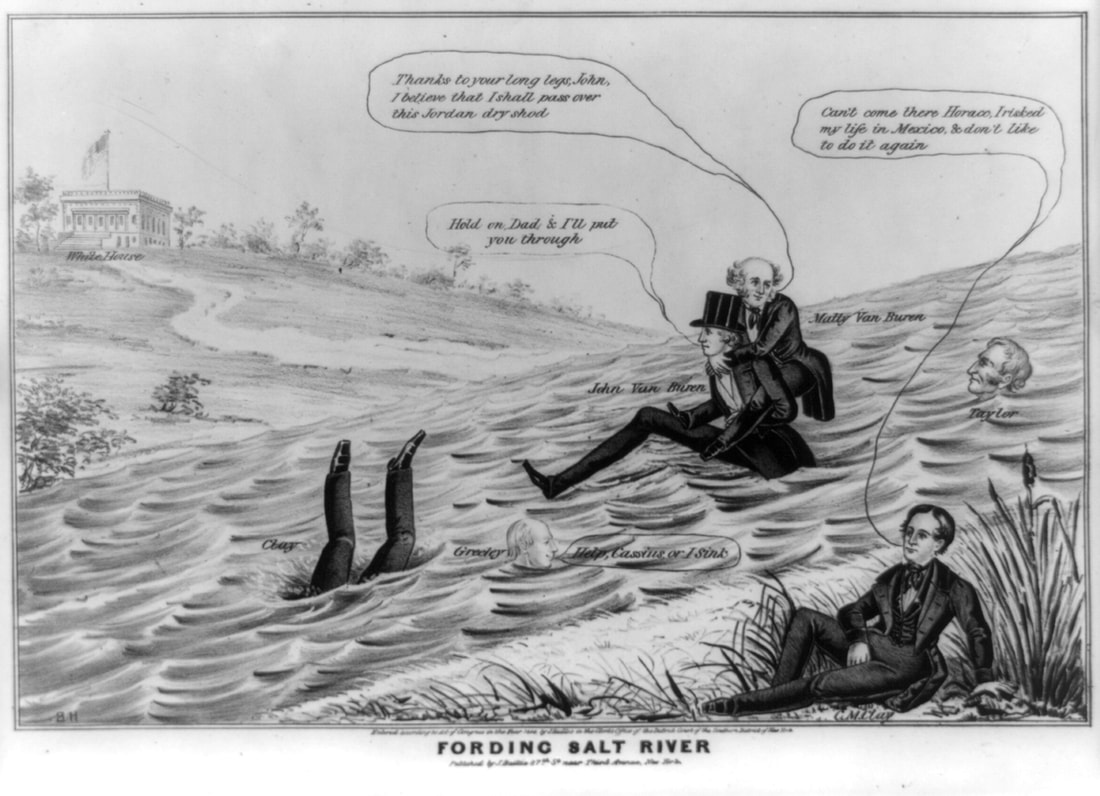

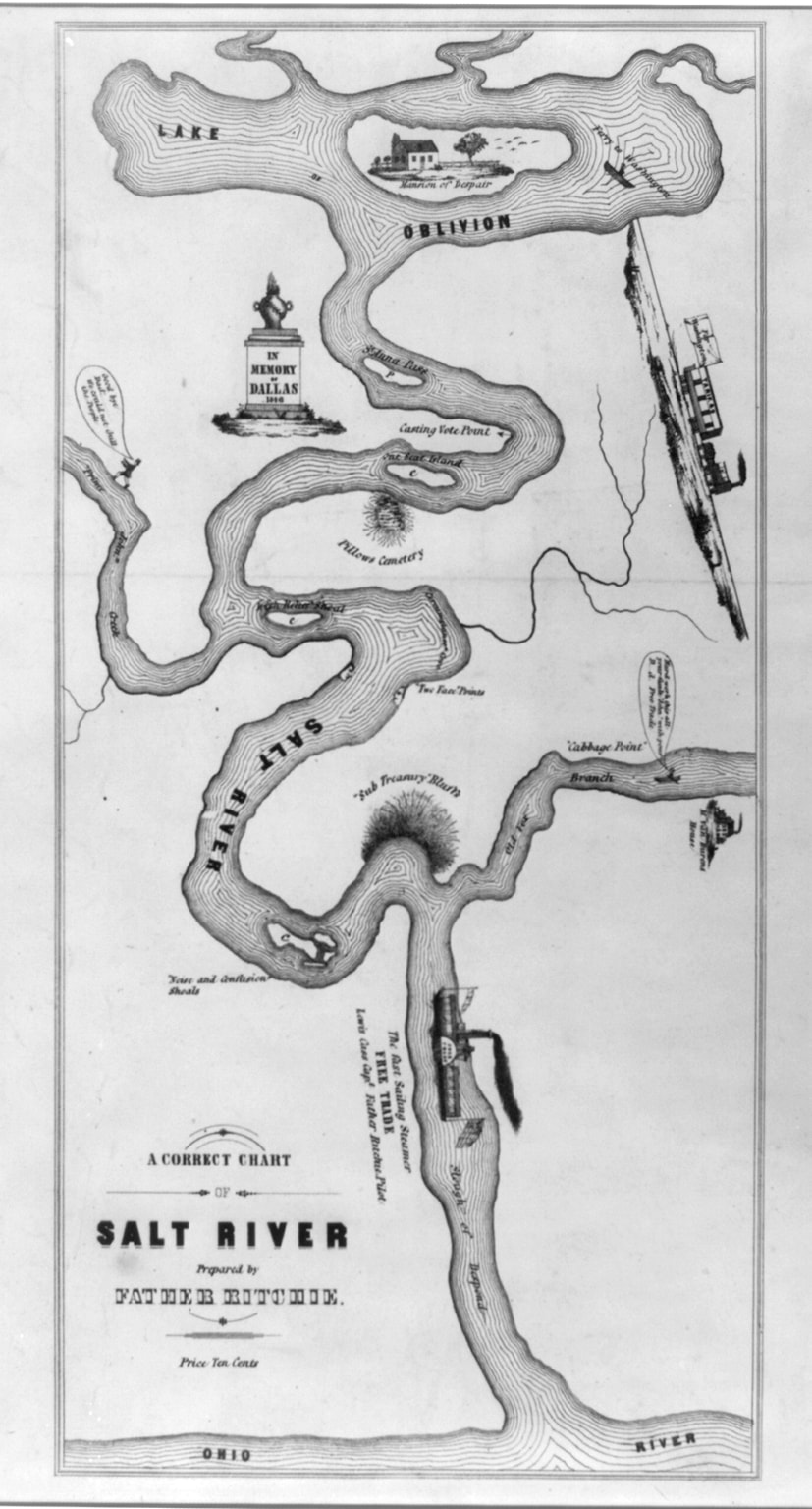

Salt River in Anderson County, about 50 miles east of Bullitt County. Note the downed tree and the rocky snag just upriver of the large boulders. (Photo by Rick Showalter) Salt River in Anderson County, about 50 miles east of Bullitt County. Note the downed tree and the rocky snag just upriver of the large boulders. (Photo by Rick Showalter) In addition to reveling in time spent camping and fishing along central Kentucky’s Salt River, Pud Goodlett was deeply interested in both politics and history. So I have to wonder if he was familiar with the nineteenth-century phrase “rowed up Salt River.” Clearing the Fog reader Liz Atchison passed along the tip about this expression, commonly used to describe a political candidate who finds himself in inhospitable waters, usually because of the machinations of a political adversary. With defeat nearly certain, the hoped for victory seems as impossible as successfully rowing up the shallow and rocky shoals of Salt River. As we wade deeply into the 2018 political season, it seems like a good time to bemuse ourselves with a colorful expression that reveals much about both our nation’s raucous political history and the central role that the unassuming Salt River played as a conduit for the unwieldy transportation of people and products to and from the mighty Ohio. In her blog, political historian Susan Barsey describes the “mythical” river as follows: “Salt River was, to begin with, a real place: a small, winding tributary of the Ohio River originating in the wilds of Kentucky. Before railroads, the Ohio was the main cross-country route for reaching the eastern cities. To go up Salt River was to leave a broad waterway, which steamboats plied daily carrying hundreds of passengers, and end up in the middle of nowhere on a dead-end stream.” (“The New Jeffersonian,” Mar 25, 2012) There appears to be some mystery about the origins of this expression of ignominious defeat. According to Charles Hartley of the Bullitt County History Museum in Shepherdsville, Ky., Franklin Pierce used the phrase in a letter dated 8 Oct 1831. Apocryphal stories tell of Henry Clay succumbing to the treachery of a Jackson Democrat who, in 1832, rowed Clay up Salt River rather than to a speaking engagement in Louisville. An 1848 political cartoon shows Zachary Taylor rowing his resigned opponent, Lewis Cass, up Salt River. Another shows Martin Van Buren being carried piggyback through the dangerous waters by his son, John, while Henry Clay plunges head-first under the water and Cassius Clay lounges out of harm’s way on the shore. Hartley cites several other possibilities for the origin of the phrase, including river pirates and a smart-mouthed local postmaster. In “Bullitt Memories: Getting Rowed Up Salt River,” he concludes that the phrase most likely came into usage in the 1790s when newspapers reported that local officials rowed a petty thief up the river to administer a punishment outside the jurisdiction of the town and perhaps outside the law. Pud never uses the phrase in his 1940s journal. Perhaps the expression had fallen out of favor by that time. Or perhaps the unsophisticated teens weren’t yet plotting the political doom of candidates they deemed loathsome. Unsurprisingly, Goodlett returns from the war in Europe with a more keenly developed political acumen. His 1950s journal makes it clear that the adult scholar would have been quick to name several politicians he would have liked to row up Salt River, if he only could have lured them to his boyhood haunt. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed