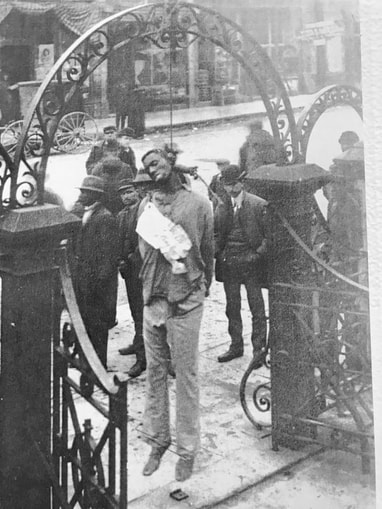

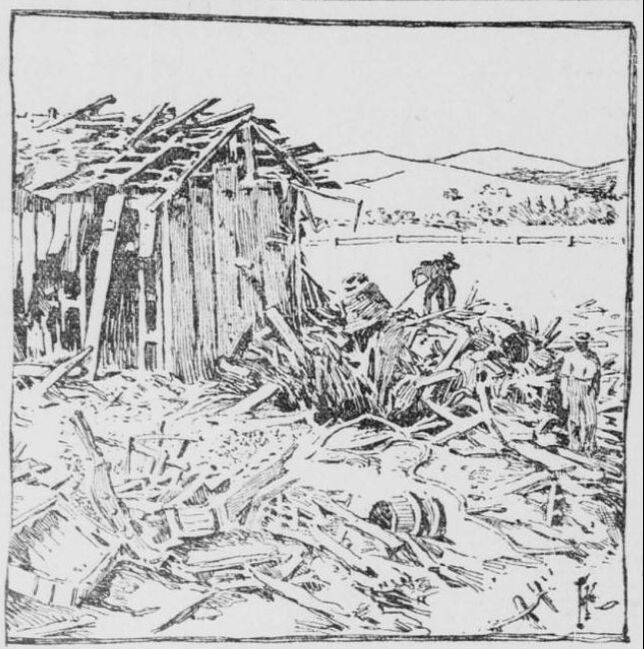

George Carter and the crowd he attracted after his hanging in February 1901. George Carter and the crowd he attracted after his hanging in February 1901. I have been haunted by the case of Ralph Jarl, the Black 16-year-old in Missouri who was shot by Andrew Lester after ringing the elderly white man’s doorbell. Jarl’s mother had asked him to pick up his two younger brothers at a nearby home, but Jarl had mistakenly approached a home on the wrong street. Everything about this situation is shocking. Lester’s behavior is reprehensible and inexcusable, no matter how broadly you interpret Missouri’s Stand Your Ground law. Jarl did nothing more threatening than ring the man’s doorbell. In my youth, someone like Lester might have yelled, “Scram, you punk!” (Well, he might have used a different epithet.) Lester also could have opted to ignore the doorbell and simply not answer the door. But Lester made the choice to shoot the teenager—twice—without exchanging any words. In the criminal complaint, Lester stated that he was “‘scared to death’ due to the male’s size.” This is the detail that caught my attention. Jarl’s family has reported that the youngster is 5’8” and weighs 140 pounds. Lester claimed Jarl was 6 feet tall. There is a considerable discrepancy here between reality and Lester’s perception. I have seen this before. In Tessa Bishop Hoggard’s book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter, Hoggard relays the story of my great-grandmother’s alleged assault by a Black man while crossing a covered bridge in Paris, Ky., in December 1900. The initial report in the Kentuckian-Citizen newspaper described the incident as an attempted purse snatching. In my great-grandmother’s words, her attacker “had brown skin, weight about 200 pounds, fairly well dressed….” Two months later, a suspect was pulled from his jail cell by a group of local men and lynched in front of the county courthouse. The victim of this extrajudicial justice, George Carter, had never been charged with my great-grandmother’s assault. He was being held in the jail for another offense. But rumors had led to suspicions that he was the guilty man, and the crime against my great-grandmother had also morphed in the prurient imaginations of concerned citizens. But, as you can see from the photo, George Carter clearly was not 200 pounds. In their rush to defend my great-grandmother’s honor, did the mob hang a man who had nothing to do with the incident on the bridge? Or was the description my great-grandmother gave the newspaper at the time of the attack yet another example of white victims reporting Black perpetrators as much larger and more physically threatening than they actually are? In her book, Hoggard also relays the story of another mob lynching in Paris in 1889, where the victim had again been described by the woman he allegedly attacked as “a large, burly Negro, weighing over 200 pounds.” We have no photograph of Jim Kelly to confirm his physical size, but the common language feels suspicious, like a trope that was cemented in the minds of a fearful white population. According to the Washington Post: “In multiple studies, people who were asked to judge the size of Black people tended to see Black men as bigger and stronger than they actually were, and gave Black children the attributes of adults. The result is that they are seen as more dangerous....In some studies, [Kurt Hugenberg, a professor in psychological and brain sciences at Indiana University] showed participants images of Black men and White men who are about the same height and weight. Participants often thought the Black men appeared larger...” Yes, Virginia, there is systemic racism. It permeates so many aspects of our lives and our interactions that even those of us who try valiantly to reject racist tropes inevitably fall under their sway. Racism is pernicious, it’s prevalent, and it’s dangerous. If we refuse to recognize that, we can’t even begin to chip away at the corrosion it has caused. And our fellow citizens will continue to pay the price.

4 Comments

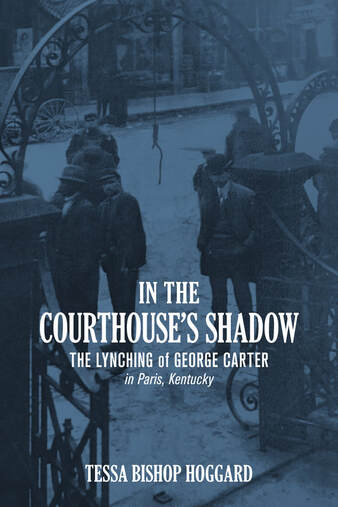

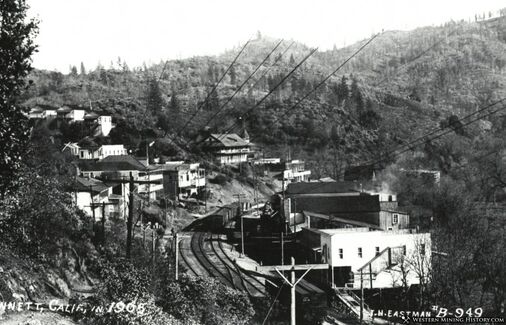

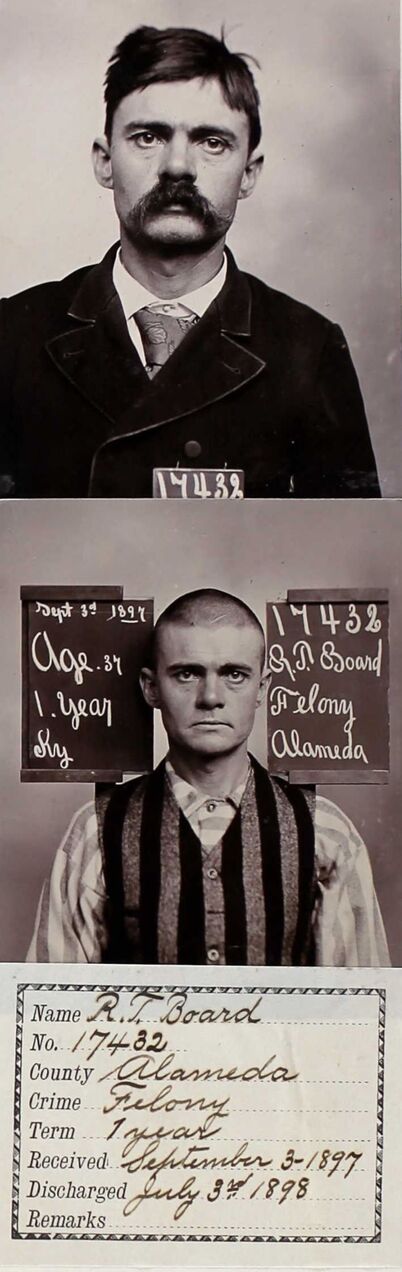

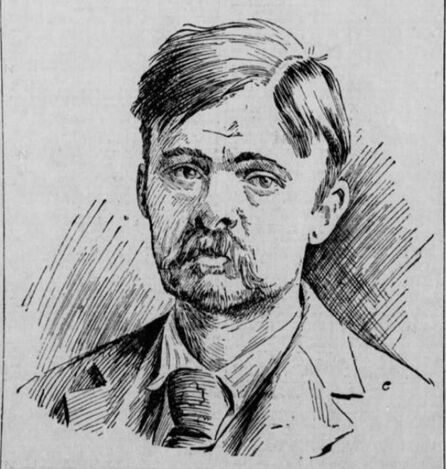

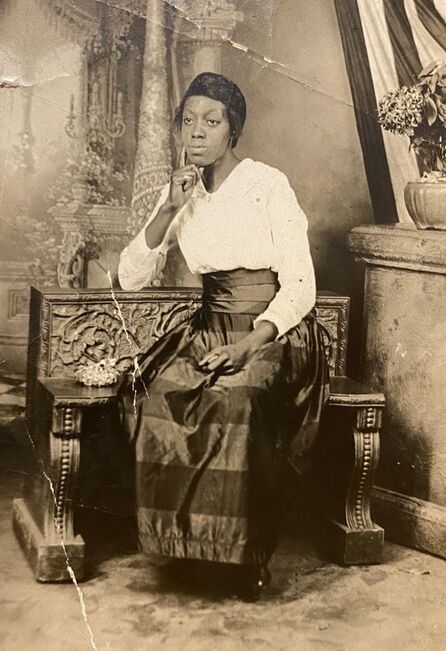

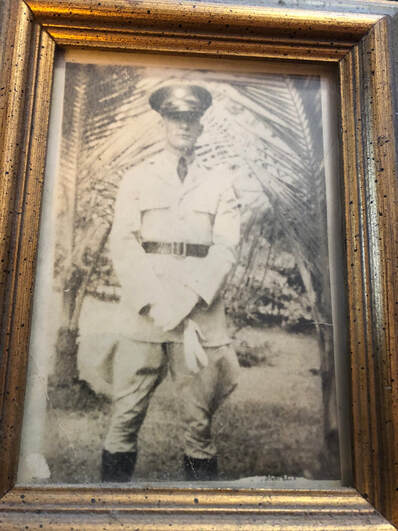

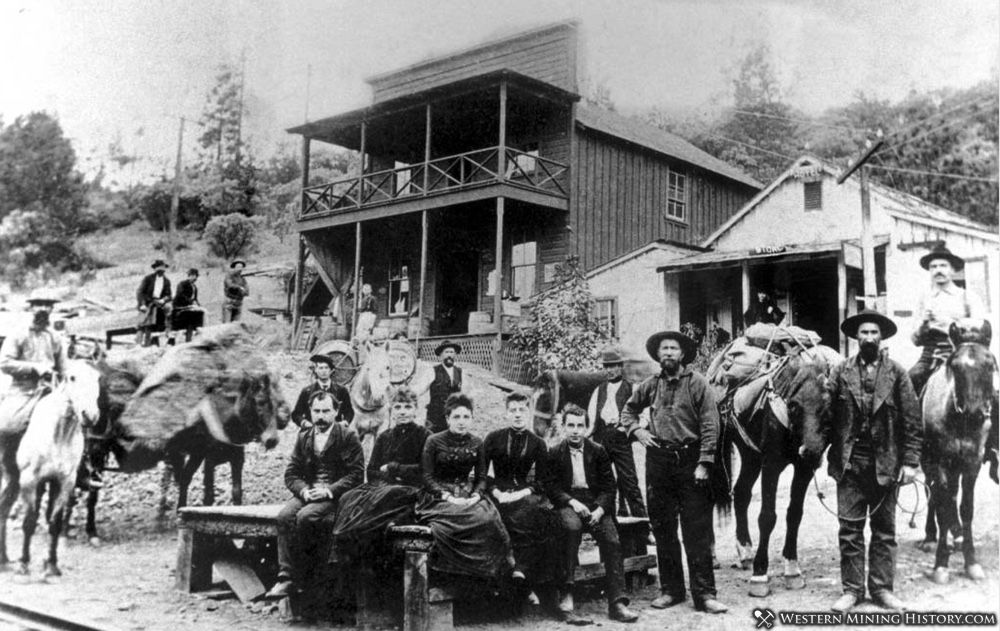

Tessa Bishop Hoggard with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of a lynching victim, George Carter. Tessa Bishop Hoggard with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of a lynching victim, George Carter. She spent years researching his family. She wrote and published a book examining the tragic story of his great-uncle. She arranged for him to meet a descendant of the woman who brought enormous grief upon his family. But she had never met him in person…until this week. Tessa Bishop Hoggard is on a mission. She recently traveled from her current home in Texas to her hometown of Paris, Ky., to round up support for her latest project: erecting a historical marker near the Paris courthouse where two Black men were lynched, in 1866 and 1901. The proposed marker will also honor a third man who was lynched nearby in 1889. Tessa’s purpose is clear: She wants to ensure that the citizens of her hometown—the old and the young—have the opportunity to confront the truths of its past. She is certain that only through acknowledging our dark history can we heal as a community and as a nation. So far her trip has been a success. After sending numerous emails and letters to local citizens and officials over the last year, she is finding that a brief face-to-face encounter seems to seal the deal. “I came prepared to recite the history of each of the three lynchings, to introduce these officials to the specific story of each individual,” Tessa told me. “But that hasn’t been necessary. As soon as they learn what I am proposing, they are offering support. I am truly flabbergasted. And elated.”  One of those victims of mob violence was Jim Bannister’s great-uncle, George Carter, who was hung on the iron gate in front of the courthouse in 1901. Carter was the older brother of Jim’s grandmother Katie—the woman who raised him. Two photos of Carter’s body hanging from the noose still exist and are reprinted in Tessa’s superb book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky. Those photos, and the newspaper description of the original incident that eventually led to mob violence, raise suspicions about whether Carter was even involved in the alleged “assault” of a local banker’s wife, Mary Lake Barnes Board, my great-grandmother. Initial reporting described the incident as an attack by “a negro man, who attempted to grab her pocket-book.” [The Kentuckian-Citizen, Paris, Ky., December 5, 1900] Many of you already know the story of how Tessa arranged from afar for me to have a public conversation with Jim Bannister in 2020. That conversation offered him an opportunity to express his grief and his frustration at not being able to uncover the truth of his great-uncle’s story, as well as his relief that it was finally being aired in public. It offered me a chance to publicly voice my regret for the horror his family endured and my apology for the role my family played in what took place. This week Tessa, Jim, and I gathered together for the first time. Emotions ran high. We took turns expressing how profoundly grateful we are for all that has transpired in the last two years. We hugged. I shed a few tears. Jim and I talk fairly often (we have to dissect Kentucky basketball on a regular basis), and I have seen him a handful of times, despite the challenges of the pandemic. But he and Tessa were in the same room for the first time. It was breathtaking to witness. In early 2023, Tessa will submit her application to the Historical Marker Program of the Kentucky Historical Society. It appears her trip this week has accomplished her goals: she has met with local officials, she has solicited letters of support, and she has revisited the scene of these tragic extrajudicial hangings. She also met George Carter’s great-nephew for the first time.  Sallie Showalter, the great-granddaughter of the woman allegedly assaulted by George Carter, with his great-nephew, Jim Bannister. Jim is holding his school photo from 1947-48, which Tessa found in her late mother’s belongings. Tessa’s interest in George Carter’s story was ignited when her mother shared a newspaper clipping she had kept from 1978 retelling the story of the hanging.  The remote community of Kennett in northern California in 1905. Some local newspapers referred to the town as “Kennet.” The remote community of Kennett in northern California in 1905. Some local newspapers referred to the town as “Kennet.” This is the third in a series of blog posts about my great-great uncle Richard T. Board, the uncle of my already infamous grandfather William Lyons Board. (Read Part I and Part II.) Many thanks again to my friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard for discovering yet another curiously dissipated ancestor of mine. It is only because of her extensive research that I am able to share these startling stories with you. As Richard Board approaches 40, perhaps he takes stock of his various schemes to find his fortune. As a young man, he evidently abandons a steady position as the deputy clerk to his father in his hometown of Harrodsburg, Ky.—or is run off for his repeated petty thefts and frauds. In 1885, when President Grover Cleveland appoints him to a federal position with the National Railway Service despite his criminal history, he steals a money order during his first trip aboard the train in New Mexico. Arriving in California sometime after serving two years in a federal prison in Illinois, he takes up with the former nurse to a soon-to-be-heiress. When no king’s ransom comes her way, he resorts to sending teenage boys into local stores to defraud proprietors. But that gets him a year in San Quentin. So what’s next? What might catch the attention of our aging antihero in California in 1899? Gold. By 1900, Richard and Mary have settled in Shasta County in northern California, near the town of Redding, with their son, approaching five years of age. The couple welcomes another baby about that time, a girl. They’re living in a cabin in the remote mining community of Kennett, where Richard is a partner in a gold mine. But it’s not long before he finds more trouble. Parties had evidently wrangled over who owned the Clipper Mine, and the courts had ruled in favor of one Alfonso di Nola over W. V. Huntington, from whom Board leased a portion of the mine. A fellow named Ross Spencer sub-leased from Board. On Monday, November 12, 1900, Spencer accompanies the newly certified owner, Alfonso di Nola, to the mine. Board appears from the mine with a gun and threatens to kill Spencer. Spencer and the three other men overpower Board and take his gun. Two days later Spencer swears out a warrant on Board for assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill, a felony. Board is arrested the next day. Simultaneously, Board is served a second warrant for a misdemeanor: passing a fraudulent $30 check at the Golden Eagle Hotel with no funds in the Bank of California to cover it. Bonds of $500 for the felony and $50 for the misdemeanor are somehow paid—or dismissed, with the help of Board’s attorneys—and Board is released from custody. On November 19 Board pleads not guilty to the misdemeanor, and the case is eventually settled out of court. On December 13 the felony charge is referred to the Superior Court. On January 4, 1901, the same Redding newspaper that has been meticulously covering the criminal charges against Board reports in the “Town and County” section that “R. T. Board, lessee of the famous Clipper mine near Kennett, spent New Year’s in this city.” Richard T. Board Jr. has once again found his way from the police blotter to the society pages. Late that same New Year’s Day, a monstrous snowstorm descends upon northern California. One hundred miles north of Redding, the town of Yreka reported 63 inches of snow had accumulated by January 3, where “snow drifts were 6-7 feet in town, and businesses came to a halt so everyone could shovel snow off the businesses and keep their roofs from collapsing.” Rather than returning home to Kennett to check on his family as the storm settles in, Board chooses to travel on to San Francisco to meet with the owners of the Clipper mine. A week later, on Monday, January 7, Mr. Robert Hart—who had been part of the group accosted by Board in November and whose life it was rumored Board had threatened even before that incident—takes another man to Kennett to check on the Board family, “thinking the heavy snow might have caused them to be in distressed circumstances.” [The Searchlight (Redding, Calif.), January 8, 1901. All subsequent citations are to this newspaper unless otherwise noted.] They discover the Board cabin has been crushed under the weight of the snow. The tableau inside is horrific. On January 17, 1901, The Feather River Bulletin (Quincy, Calif.) runs the following headline: “Five Days the Baby Lived While Starvation and Gangrene Sapped Life.” The article included this report from the Free Press: Mrs. Board was killed by a falling of the roof. She had perhaps doubted if it would hold up under the great weight of snow. She may have been in fear for hours, and had drawn on a pair of overalls as if to be ready to flee the cabin if necessary. She had gone to the buggy where her baby lay. A key carried in her hand she thrust between her teeth that she might use both hands to lift the baby. As the mother bent over, a corner of the roof gave way and the timbers fell upon her, crushing her across the baby buggy. Her throat fell across the wicker side and she was strangled to death. The lad was not hurt by the falling roof. Tracks around the cabin showed where he had crawled out and run about, probably shouting, only to be mocked by the solitude. At last weakened by starvation he had lain down by his mother's upright dead body and exposure soon brought about his death. The child in its perambulator was shielded from the cold blasts. It could not freeze, but slowly it starved. The mother's body pressed the child's abdomen and circulation in the lower half of the body had ceased. Though the child was alive after five days, when discovered Monday, its tiny feet had turned black and gangrene was reaching upward toward the knees. The little one lived only a few hours after being released. Removing the bodies is not an easy task. “It was found necessary to make an improvised sled from one of the doors of the house and upon it the bodies were drawn to Kennet over the deep snow.” (January 8)

As word spread of the tragedy, the newspapers speculate about Richard Board’s whereabouts. His horse had been found at Kennett, probably at the train station where he had embarked first to Redding and then to San Francisco. Not being able to ascertain where he was during the storm, reporters don’t hesitate to admonish him for having abandoned his family in a time of peril. He is accused of longtime negligence. Three days later he is sighted in Redding. “Thursday evening R. T. Board passed through Redding on the northbound California express en route to Kennet, from where no one knows…Early Friday morning [he] started for the Clipper mine.” (January 11) When he arrives at Kennett, he finds his family’s coffins on the platform at the station. Arrangements had been made by Mary’s sister, Mrs. Martha Beadle Gowans, to transport the bodies for burial near her home in Sonoma County. Richard has a week to come up with a story. On Saturday, January 19, he returns to Redding to make a statement to the newspaper. He tells a convoluted tale of having asked a friend to check on his family as the snowstorm arrived and he departed for San Francisco, and of three men ordering him out of Kennett when he arrived to find his family’s remains at the train station. The newspaper immediately counters its recent accusations of negligence with a rather fantastic tale based on Board’s personal report. The next day, the headline offers this new narrative: “R. T. Board Experiences a Tragedy of Woe.” The article gushes with new-found sympathy for the bereaved widower: “But few men suffer the lot of Richard T. Board of Kennet. While far from his home and loved ones on business, the result of which meant the very means of sustaining life within them, the unfortunate man was robbed of his wife and two babies by one fell stroke.” His woes are indeed piling up. On that same Saturday, Board appears before the superior court judge on the felony assault charge. When the district attorney reduces the charge to simple assault, Board changes his plea to guilty, claiming that his actions were in response to Spencer coming to his home back in November at a time when he was away and ordering his wife and children from the house while insulting his wife with “unbecoming language.” (January 25) In lieu of a $180 fine, which Board cannot pay, the judge sends him to the county jail for 90 days. Board soon discovers more anguish for his baleful lot. As the Redding Searchlight continues its rapid reformation of its opinion of Board—who’s now sitting in the county jail—it writes the following headline on February 15: “Troubles Come in Battalions: More Sorrow for R. T. Board, to Whom the Fates Have Been Unkind Indeed.” The article relays that “After having passed through troubles more than sufficient to try the stoutest heart [Board] learned by dispatches in the coast’s papers that his sister-in-law has been made the victim of a negro fiend.” The sister-in-law referenced would be my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Board, who had allegedly been assaulted on the 2nd Street bridge in Paris, Ky., in December. That incident resulted in the lynching of George Carter in front of the Bourbon County Courthouse on February 11, 1901. In response, Board writes to the editor of the Redding Searchlight from his jail cell: “My poor old mother must be heartbroken….It is almost enough to drive me crazy, but I will overcome it and yet make my way through this world, in a way which will be a blessing in the memory of my dear ones.” Upon his release from jail in April, the San Francisco Chronicle (April 20, 1901) further embellishes on his family’s plight in an article headlined “Victim of Many Misfortunes”: “Since his incarceration his brother’s wife has been assaulted by a negro at Paris, Ky., and the negro burned at the stake.” Those of you who follow this blog know that is a false statement, yet there appear to be no bounds for newspapers at the time when invention fosters sensationalism that sells papers. Richard T. Board Jr., with his privileged upbringing, regular access to men of power, and his recognition of the authority of the press to shape a story, can construct his family’s narrative, and our nation’s recorded history, through a series of glib conversations and eloquent letters. Ultimately, what was Richard’s response to his “many misfortunes”? As seemed to be the Board family ritual, he took the next train out. The next month, May 1901, he leaves Kennett for Los Angeles to work for the Sierra Railway Co. of California, which was then engaged in a large tunnel project. Accounts seem to indicate he spent a relatively quiet year or two there, working as an assistant agent and a car cleaner, before returning to the mines in northern California, and to his life of petty crime.  Richard T. Board’s intake photo (top) and discharge photo (bottom) from San Quentin Prison. His offense is listed as “felony”—probably a clerical error since he was convicted of forgery. Richard T. Board’s intake photo (top) and discharge photo (bottom) from San Quentin Prison. His offense is listed as “felony”—probably a clerical error since he was convicted of forgery. This is the second in a series of blog posts about my great-great uncle Richard T. Board, the uncle of my already infamous grandfather William Lyons Board. (Read Part 1) Many thanks again to my friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard for discovering yet another curiously dissipated ancestor of mine. It is only because of her extensive research that I am able to share these startling stories with you. Nine years after being released from federal prison in Illinois, where he served two years for stealing a $163 money order from a mail service train on its way to Santa Fe, N.M., Richard T. Board Jr. sits next to his attorneys in another courtroom, this time in Alameda County, Calif., with a baby in his arms. It’s August 1897. During the trial, he does not deny that he endorsed a $50 check with his kindly benefactor’s name—a woman who had provided him shelter on her ranch when he was destitute—and then asked a 15-year-old boy he approached in the street to have it cashed at Kahn Brothers shoe store. But he claims that he was driven to this criminal act only by the dire circumstances of his poverty. After losing his job at Judson Iron Works, he had been struggling to find work and was searching for a way to feed his family, including his wife, there in the courtroom anxiously watching the proceedings, and the baby he continues to hold. He also makes a point to mention that he and his wife, Mary, had recently lost another child. How had Board gotten into this predicament? After being discharged from the Army in July 1894, he had remained in the San Francisco area and married Mary Hannah Beadle in December. He may have done a brief stint in the Marine Corps, serving at the Navy Yard on nearby Mare Island. It’s more certain that he joined the National Guard in April 1896 and was honorably discharged in September. Now in his mid-30s, these enlistments may well have been his best shot at a steady paycheck. The U.S. military services were evidently happy to accept a convicted felon in their ranks. But now he finds himself in yet another courtroom facing yet another term in prison. Newspapers across the country are covering this trial, just as they did his first. Board is repeatedly identified as “a protégé of ex-Senator Joe Blackburn of Kentucky [whose] father was for thirty years clerk of the United States circuit court of Kentucky.” [The Omaha Evening Bee, 04 July 1897] No newspaper mentions the younger Board’s multiple arrests for forgery or theft. None mentions his previous incarceration. Board tells them exactly what he wants them to print, which is whatever he thinks will help his case. In the end, the judge—clearly affected by the pathos of the situation before him—gives Board the minimum sentence for his offense. Board is sent to San Quentin for one year. Is it possible that the judge was not aware that Oakland police had a warrant for Board’s arrest a year earlier for similar crimes: sending boys into butcher shops and breweries to cash checks and thus defraud the proprietors? According to the San Francisco Call, a string of these crimes had again been reported in the weeks leading up to Board’s arrest in June. His forgery of the check in the shoe store was not an isolated crime committed in a moment of desperation. Nevertheless, it’s almost certain that the judge was aware of who Mary Beadle Board was. Just as it’s almost certain that Richard Board knew who Mary Beadle was long before he ever left St. Louis for his Army stint in San Francisco. Was it mere happenstance that he landed in the very city where one of the nation’s most sensational trials was taking place? Or did Richard Board arrive in California with designs on the aspiring teenage heiress Florence Blythe or her nurse, Mary Beadle? Let’s jump back a bit and pick up Mary’s story.  Heiress Florence Blythe Hinckley, from the San Francisco Chronicle, 01 December 1892. Heiress Florence Blythe Hinckley, from the San Francisco Chronicle, 01 December 1892. On April 4, 1883, real estate tycoon Thomas Henry Blythe died suddenly at his home in San Francisco at age 60. A native Englishman of some reserve and mystery, he had amassed a $4 million fortune and owned vast property in San Francisco, San Diego, and Mexico, as well as a mining property in Nevada. Upon his death, more than 100 women came forward claiming to be his widow or his heir. Ten-year-old Florence Blythe, whose family asserted she was Blythe’s illegitimate daughter and sole legitimate heir, was brought to California from her home in England shortly after her father’s death by her maternal grandfather, Mr. James Crisp Perry, his wife, Kate Beadle Perry, age 30, and her sister, Mary Beadle, age 24. Mrs. Kate Perry was frequently identified in the press as Miss Blythe’s “guardian” and Mary Beadle as her “nurse” or as a servant in the Perry household. Initially, no will could be found, and the courts wrestled with Blythe’s estate until the matter was sent to trial, six years after his death, on July 15, 1889. A verdict would not be reached in the complicated case until 1895. Five days after the trial began, one of the attorneys for Florence Blythe announced that he had located Mr. Blythe’s missing will in Los Angeles, where it had been stashed by Mr. Blythe’s housekeeper, who claimed after his death to be his widow. The will bequeathed the entire estate to his young daughter, Florence Blythe. The attorney also had letters written by Mr. Blythe to his daughter and his daughter’s mother, many which had contained money for her support. The almost cartoonish melodrama of the trial was breathlessly covered by newspapers across the country, including in St. Louis, where Richard Board could follow the lurid details in the Globe-Democrat after he got out of prison. He likely was familiar with all the major players, including Mary Beadle, who with her older sister and brother John were put on the stand to testify about their history with their young charge, Florence Blythe, when they all lived in England. When Richard Board lands in San Francisco for a stint in the Army in April 1892, he may have had designs on the young heiress herself. But on June 22, 1892, 19-year-old Florence Blythe surprises her loyal followers by marrying the boyish Fritz Hinckley, 23, heir to his father’s foundry business. (Fritz dies tragically five years later after suffering appendicitis while traveling with friends to Salt Lake City.) So perhaps Richard then sets his sights on Mary, who expects to receive a sizable sum ($10,000-$15,000) for her services working for the Perry family once the estate is settled. And on December 3, 1894, Richard marries her. But things don’t go as planned for the newlyweds. Florence Blythe Hinckley disapproves of the marriage (because Board had made overtures to her?) and casts Mary aside. Florence’s grandfather, James Crisp Perry, dies and his wife Kate, Mary’s sister, remarries. The Boards find themselves abandoned by Mary’s family and penniless. Before her husband’s trial begins, Mary announces she intends to sue the Blythe Hinckley estate and her sister for the money she feels she is due. A few months after Board’s trial, while Richard remains incarcerated in San Quentin, Mary’s sister Kate, now Mrs. John E. Byrne, receives $250,000 from the heiress. From all we know, Mary patiently waits for her husband’s return from San Quentin. Three months after his homecoming, Richard Board is working in the nitrate house at Judson Dynamite and Powder Works in Berkeley when there is an explosion in the adjoining mixing room. The building is destroyed and the two men who had been in the mixing room are “blown to atoms.” [Evening Sentinel, Santa Cruz, Calif., 24 October 1898] Board is thrown 60 feet but receives only lacerations. Only a wooden bulkhead had separated him from the 200 pounds of gelatin (guncotton, nitroglycerine, potassium nitrate, and other ingredients) that was being made into dynamite next door. Board described his experience to a reporter from the San Francisco Call’s Oakland office: “A little after 8 o’clock the explosion occurred, but it came so suddenly that I hardly heard anything. In fact I did not have time to think before I was in the air, with lumber and dirt flying all about me….I cannot describe the sensation…for it was most peculiar. First I seemed to be falling into a deep abyss, then the walls seemed to all cave in and I was drawn right up into space.” After yet another encounter with fickle fate, Richard T. Board Jr. walks away nearly unscathed. Soon his remarkable luck will protect him once again, while tragedy befalls all those around him.  Richard T. Board Jr., from a drawing that appeared in the San Francisco Call in 1897. More on that story in Part II. Richard T. Board Jr., from a drawing that appeared in the San Francisco Call in 1897. More on that story in Part II. This is the first in a series of blog posts about my great-great uncle Richard T. Board, the uncle of my already infamous grandfather William Lyons Board. Many thanks to my friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard for discovering yet another curiously dissipated ancestor of mine. It is only because of her extensive research that I am able to share these startling stories with you. The Republicans were outraged. Couldn’t this administration appoint any officials who weren’t already corrupt or proven criminals? Grover Cleveland, the newly elected president, was the first Democrat to sit in the White House since the Civil War, and newspapers across the country railed against his inept hiring practices. The St. Albans [Vermont] Weekly Messenger repeated what was evidently a common refrain: “Another jail bird appointed to office by the democratic administration.” The article goes on to say that soon after Richard Board, age 25, was appointed clerk for the Rincon to Deming, N.M., route of the U.S. Railway Mail Service, prominent citizens in his hometown, Harrodsburg, Ky., notified the federal government that “Board was under three indictments for forgery, and had been three times arrested in Cincinnati for getting money under false pretense, once in Texas for robbery and twice for theft in Kentucky.” I have not been able to corroborate all these claims. Nonetheless, how on earth had young Richard Board gotten this plum assignment in the 15-year-old Railway Mail Service? Richard T. Board Jr. was the eldest of three sons of Richard T. Board Sr., the highly respected longtime circuit clerk in Mercer County, Ky. (county seat, Harrodsburg). The son had worked as the deputy clerk to his father for at least a couple of years. Richard Board Sr. was well known among Kentucky’s political powerbrokers. The First Comptroller of the Treasury in the Cleveland administration was Hon. Milton J. Durham, a native of Danville, Ky., one county south of Mercer. Durham had evidently sponsored Board’s appointment upon the recommendation of Kentucky’s Democratic U.S. Senator Joe Blackburn (younger brother of Kentucky Governor Luke Blackburn, whose term had ended in 1883). It probably didn’t hurt that the assistant postmaster general during the Cleveland administration was Adlai Stevenson, a Kentucky native who evidently was eager to fire Republican postal workers and replace them with Southern Democrats. This was the machine behind young Richard’s federal appointment. Somewhere along the way, no one bothered to ask about his character. Two weeks after Board was named to the post, Comptroller Durham, according to the St. Albans newspaper, “got a lively letter from a friend in Kentucky, reciting Board’s criminal record in full. The letter concludes with the prediction that Board would steal something before he had been in the service a month. The prediction was fulfilled. Before the warning note was written Board had stolen a money order for $163.” Board had been appointed to the position on July 7, 1885, dismissed on July 30, and, on August 17, was arrested in St. Louis where he previously had been living with his wife of eight months, Fannie Mace. The St. Louis Globe-Democrat claimed he had illegally used his Railway Mail Service transportation card to travel back to Missouri after his dismissal. Board was unable to pay the $1,500 bail and was remanded to jail in St. Louis. After being transferred to a Santa Fe jail, he stood trial in Socorro, N.M., in March 1886 and was found guilty of robbing a registered letter from a train heading to Santa Fe. Never one to blame himself for his misfortunes, Board evidently claimed, and The Sierra County Advocate of Kingston, N.M., reported, that “His downfall [was] attributed to an immoral female.” After the trial, federal marshals brought Board back to St. Louis and he was delivered to Southern Illinois Penitentiary at Chester (now Menard Correctional Center), 60 miles southeast of St. Louis, to serve a two-and-a-half-year term. On February 7, 1888, while his oldest son was still in prison, Richard T. Board Sr. died of a paralytic stroke at age 62. According to the Stanford, Ky., Interior Journal, he had been “on the street apparently well an hour before.” Newspaper documentation shows that Richard T. Board Jr. had indeed been arrested multiple times for forgery and theft before he was incarcerated in Illinois. Reports indicated that his father had done all he could to honor his son’s debts and rescue him from his scrapes with the law. In September 1883, records show Richard Board Jr. had been arrested in Cincinnati for forging his father's name to a check at the National Saloon. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, “In his pocket was found a touching letter from his brother in Harrodsburg, Ky., begging him for the sake of his folks to behave himself.” That brother would be my great-grandfather, William Ellery Board, father of William Lyons Board. A few months later, in January 1884—while working as a bookkeeper in St. Louis, a few months before marrying Fannie—Board passed a false $10 check written on a Harrodsburg bank to the Pacific Express Company. In lieu of an $800 bond, he went to jail. I can only assume that Richard Board Jr. returned to his wife in St. Louis after he was released from prison on May 4, 1888. By June 1892, however, Fannie had filed for a divorce from Richard Board, accusing him of “brutality and general indignities,” according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. By then, Board was already gone. On April 30, 1892, at 31 years old, he had enlisted as a private in the Army and was stationed at the Presidio in San Francisco. Richard Board Jr. had landed in the wild west, and he would spend the next 25 years wreaking havoc up and down the coast, leaving tragedy in his wake.  Katie Carter, the younger sister of George Carter and the grandmother of Jim Bannister. George Carter was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901. Photo provided by Jim's daughter, Cheryl. Katie Carter, the younger sister of George Carter and the grandmother of Jim Bannister. George Carter was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901. Photo provided by Jim's daughter, Cheryl. On February 23, 1900, Rep. George Henry White (R-N.C.), the sole Black U.S. lawmaker at the time, gave an impassioned speech on the House floor about the antilynching legislation he was proposing. The bill would make mob violence that resulted in the victim’s death a federal crime of treason to be tried in U.S. courts. White had felt compelled to act after witnessing the bloody Wilmington, N.C., race riot a little over a year before, during which a mob of white locals toppled the city’s multiracial government and ruthlessly murdered an estimated 60 innocent Black citizens. After White’s speech, his fellow congressmen applauded his words but failed to pass the bill out of committee. Thirty-five years after the Civil War, Southern devotion to states’ rights was still paramount. White called out some of his colleagues who had spoken against heinous lynchings in their own communities. In White’s view, these legislators would not countenance federal legislation because “this would not have accomplished the purpose of riveting public sentiment upon every colored man of the South as a rapist from whose brutal assaults every white woman must be protected.” [Washington Post, February 21, 2020] A year later, on February 11, 1901, a determined mob of local townsmen hung George Carter in front of the Bourbon County Courthouse in Paris, Ky. His crime? According to news reports: an attempted purse snatching. According to rumor and innuendo: rape.  My great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. My great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. The woman George Carter allegedly accosted was my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Board. The eight-year-old boy who identified Carter as his mother’s assailant was my maternal grandfather, William Lyons Board. There are reasons to question whether George Carter was indeed the man who assaulted my great-grandmother. There was no trial, no presentation of evidence. There was almost certainly no capital crime. In her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky, Paris native Tessa Bishop Hoggard scrutinizes the contemporaneous documentation and then offers a riveting account of the lead-up to the encounter with my great-grandmother and its chilling aftermath. The hanging also plays a pivotal role in the novel I wrote about my grandfather, Next Train Out. Of course, no one in that Paris, Ky., mob was ever identified or arrested. No one was charged or convicted of murdering George Carter. There was no federal hate crime or antilynching law on the books, because Congress had failed to act the year before. It was not until 1920 that “Kentucky became the first southern state to pass an antilynching law.” [John D. Wright Jr., “Lexington’s Suppression of the 1920 Will Lockett Lynch Mob,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 84, no. 3 (1986): 263-79.] This month, 122 years later, after 200 failed attempts, Congress finally succeeded in passing the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, named in honor of the 14-year-old boy who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. After President Biden signs the bill into law, a lynching resulting in death or serious bodily injury can be prosecuted as a federal hate crime punishable by up to 30 years in prison. It’s too late for George Carter, of course, or for the estimated 2,000 people who were lynched in this country after White’s original bill failed. But perhaps it’s a sign that our nation’s citizens are finally ready to take some initial steps toward ensuring justice prevails when racial hate crimes are committed. Just last month a Georgia jury found the three white men involved in Ahmaud Arbery’s murder guilty of federal hate crimes. The next day the three Minneapolis police officers who remained inert as Derek Chauvin slowly killed George Floyd were all found guilty of violating Floyd’s civil rights. It may feel like way too little way too late, but perhaps we can sense a slight rebalancing of the scales of justice. Perhaps we are moving at a snail’s pace toward that more perfect union where all men and women truly are created equal. Despite current efforts in statehouses across the country to restrict discussions of our nation’s documented history relating to racial injustice and oppression, perhaps these concrete actions are signs of movement in the opposite direction, toward transparency and a more honest reckoning of our past. We all need to feel uncomfortable about the atrocities that have been committed in this nation to buttress unequal power structures. We need to feel shame. And then we need to take action to address the lingering institutions and sentiments that perpetuate these injustices. Rep. Bobby Rush, D-Ill, the longtime champion of the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, said after the bill passed: “Lynching is a longstanding and uniquely American weapon of racial terror that has for decades been used to maintain the white hierarchy…. [This bill] sends a clear and emphatic message that our nation will no longer ignore this shameful chapter of our history and that the full force of the U.S. federal government will always be brought to bear against those who commit this heinous act.” [NPR, March 7, 2022] Bill signedOn Tuesday, March 29, 2022, President Biden signed into law the Emmett Till Antilynching Act. Till’s cousin, Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., the last living witness to his abduction, said in response, “Laws make you behave better, but they cannot legislate the heart.” Let’s hope the hearts of all Americans are slowly recognizing the injustices that have stained our nation since its inception. eventOn Saturday, March 26, 2022, Tessa Bishop Hoggard and I participated in a Zoom virtual conversation hosted by the Paris, Ky., Hopewell Museum. We discussed the 1901 lynching of George Carter and how that dark episode prompted both of us to write our books. Connecting with Tessa ultimately led to my friendship with George Carter’s great-nephew, Jim Bannister.  In June 1946, John C. “Pud” Goodlett travels third class from Bamberg to Le Havre before boarding a ship home. In June 1946, John C. “Pud” Goodlett travels third class from Bamberg to Le Havre before boarding a ship home. My father, the rule-follower. At least now I know where I get it. “It will always be a source of regret to me that I followed Army regulations and failed to keep a diary of my days in Europe from Jan 1945 to June 1946.” Pud wrote that in the Preface to the journal he started well after the war, in February 1953, while employed as a research associate at Harvard Forest in Petersham, Mass. Though this journal focuses on his efforts to complete his doctoral dissertation, his interactions with other scientists and their research projects, and his introduction to academic and work-life politics, he is nonetheless just a few years removed from his march across Europe as a lieutenant in Patton’s army. Every now and then, wartime memories would interrupt his typical journal remarks about New England weather or frost heaves, with no elaboration. The specific horrors or searing experiences that prompted a terse reference were not permitted to stain these pages. For example, here is how he opened his post on 31 March 1953: Eight years ago about this time I was crossing the Rhine at Mainz. This afternoon about 1600 the sun broke out and stayed until sunset. We’ve had about a week of lousy weather—rain or cool and cloudy. Rain gauge showed almost 3 in. for last week. Worcester had 8 in. rain in March—more than any March since 1936, the year of disastrous floods. Last weekend the Conn. and Saco Rivers were on the rampage. … After crossing the Rhine to Frankfurt, Pud and his unit would follow Germany’s 6th Infantry Division east to Mühlhausen, south to Erfurt, through the Thüringer Wald to the Danube at Regensburg, and eventually on to Austria. They encountered increasingly demoralized enemy forces and human atrocities unlike any the modern world had seen. My father witnessed all of this first-hand. As an intelligence staff officer and a battalion S2, Pud was responsible for relaying to his commander the threat that lay just ahead: the number of and preparation of the enemy forces, the terrain and battlefield conditions, and the risks to a successful completion of the mission. The accuracy of his assessment and the clarity of his communication could save—or cost—American lives. Amid the chaos of war, the Allied forces had one goal: the defeat of Hitler and the forces he had aligned behind the Nazis. The enemy was so clear, the purpose so important, that young American men, including members of my family, eagerly volunteered to fight, sometimes before they were of legal age to join the military. I recall this family history, of course, as Vladimir Putin sends Russian forces westward into Ukraine. Putin has his own reasons for this aggression, claiming, falsely, that the democratically elected Ukrainian government grabbed power illegitimately. Putin wants us to believe he is fighting the Nazis--“like 80 years ago.” He is not. But he believes that he can win support among Russian people if he resurrects the horror inflicted on millions of Russians during the Second World War. The Nazis were the clear enemy then, so they will be a convenient enemy now. We have all seen the rising influence of Nazi sympathies in recent years. It is a cancer that seems to metastasize unchecked in dim corners of civilized society. I expect Ukraine, like most Western countries, has some number of Nazi sympathizers. It is not, however, a nation ruled by Nazis. Our parents and grandparents fought the evil that was Nazism. As did the parents and grandparents of Russian citizens. And Ukrainian citizens. Putin’s forces today are not fighting Nazism. They have been conscripted to fight Putin’s war to realize his fever dream of an expanded Russian state. It is Putin who is using Nazi tactics like disinformation and a nationalistic love for the motherland to further his own totalitarian ambitions. We see this clearly. We ache for the Ukrainian and the Russian citizens; the refugees and the nations that have opened their arms to them; the Russian soldiers who are being sent to fight their neighbors and their family members; the Ukrainian forces that are withstanding the assault of a larger, better equipped opponent; the Ukrainian citizens who are fighting back in the streets; the Ukrainian officials who are standing strong in the face of mortal threat and the physical destruction of their cities and their homes. Experts tell us this tragedy is still in its opening act. It’s hard to know how it will play out. We can only hope, once again, that the rest of the world can find the courage to stop a madman.  The author’s father, Corporal Joseph P. Anthony, circa 1940 in Hawaii. The author’s father, Corporal Joseph P. Anthony, circa 1940 in Hawaii. Joe Anthony, of Lexington, Ky., wonders whether Americans have what it takes to defeat our 21st-century enemy. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. During the 1940s, do you think our parents and grandparents would sometimes complain to each other? “I’m so tired of news about the war. Can’t we talk about something besides the Pacific Front or Allied landings?” I’m sure they did, occasionally, but they knew the war was center stage. Covid is our war. It doesn’t matter if we’re “over it.” Our enemy, Covid, is endlessly crafty, energetic, and vicious. I know. I recently spent 16 days in the hospital and nine days in a rehabilitation facility after contracting the virus. I was fully vaccinated and boosted, and it nearly broke me. As in all battles, it’s ourselves that matter even more than our opponents: our vanities, our fears, our prejudices, our malice. If we can manage ourselves, we will vanquish the enemy. George Will, the conservative columnist, wondered if our country, as constituted now, could win the Second World War. I wonder, too. It isn’t only the reluctance to sacrifice for the common good; it’s the refusal to believe the credible. Millions indulge themselves with fantastic speculation backed by no evidence and sometimes no logic and reject that which comes with freight-loads of scientific proof or that which they witnessed—re January 6th—with their own eyes. That refusal to acknowledge basic reality breaks down community, too. We can’t even get to the point of disagreeing. A sub-group of Americans in the ’40s, die-hard America-Firsters, pushed the theory that FDR had been behind the attack on Pearl Harbor. But they were called nuts by the huge majority. Now there is no “nut” theory that doesn’t get a hearing and eventually, it seems, a substantial following. Our parents and grandparents may have grumbled, but they collectively pulled themselves together: gathered scrap, rationed, and sent their sons to fight. They accepted hard truths, facts they didn’t like. They knew the news wasn’t always going to be good and didn’t reach for a scapegoat to blame. Well, not usually at least. And when the dreaded telegraph arrived, they grieved but knew their sacrifice went beyond themselves—went out to the country they loved. They got some comfort from knowing that. Though death is always solitary, the country they sacrificed for came back to them in a collective embrace. We love the same country. And if we truly love that country, it will love us. Can we do less than our previous generations? Can we even imagine loving our fellow Americans?  Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, surveys Georgia’s political landscape. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. Once again, it appears the state of Georgia will be the center of the political campaigning universe in the United States during 2022. With David Perdue’s entry into the gubernatorial race, the plot thickens. Months ago, when Herschel Walker announced his candidacy as a Republican opponent to Sen. Rev. Raphael Warnock, I started writing a post entitled “Run, Herschel, Run (right back to Texas).” Now his campaign is just one ingredient in the Georgia political stew. I still think it’s unethical for Herschel Walker to “move back” to Georgia two weeks before filing as a candidate to represent the people in a state he left in 2011. Walker also has a history of mental illness and alleged domestic violence. But this is politics, folks. Laws and ethics don’t seem to influence (or apply to) the behavior of many political figures. While some of us may believe it’s unethical, under the Constitution it is perfectly legal for him to run. Of course, University of Georgia football is a religion all its own, so Walker is like a god to many Dawgs fans. Plus, he may get the endorsement of 45, which will garner him much favor with the far-right crowd. The former president could be a significant problem for Brian Kemp in his campaign for re-election as Governor. If you recall, Kemp refused to help “find votes” to reverse Biden’s win in the Georgia presidential election. Now David Perdue presents a challenge as well. Democrats are quietly celebrating the entry of Perdue, as his candidacy will likely force a Republican run-off election. That makes three Republican gubernatorial candidates, including Big Lie supporter Vernon Jones. I’m sure there are bookies taking bets on who 45 will back: Perdue or Jones? What might he say or do to retaliate against Kemp’s disloyal behavior? Stay tuned for what is bound to be the worst kind of reality TV. Just a few years ago, the idea that Georgia would elect two Democratic U.S. Senators, and that we were a swing state that could win Democratic control of the Senate, would have been laughable. In many Georgia communities, the Democratic party did not field candidates in local and state legislative races for roughly 20 years. I have no doubt that voter registration and GOTV efforts for 2022 will be extraordinary. Stacey Abrams, her supporters, and the Fair Fight* organization excel at both. I believe electing Stacey Abrams Governor of Georgia will bring joy, hope, and continued motivation to Democrats, most African Americans, and many women. It will also represent a monumental achievement in a deep south state steeped in racism since colonial times. Sixteen miles east of Atlanta lies Stone Mountain Park, where the largest bas-relief artwork in the world—featuring three Confederate leaders—was completed in 1972. The 90-foot-tall engraving looms over the patrons of the public park from the façade of Stone Mountain. A portion of funds for the Confederate memorial project came from the federal government’s 1925 issuance of fifty-cent commemorative coins featuring two Confederate generals. (Yes, that’s right. The federal government issued coins to commemorate traitors, and to help fund a monument to them.) The Ku Klux Klan held a revival during a 1915 cross burning atop Stone Mountain. According to an article by Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Joshua Sharpe, the most recent KKK permit request to burn a cross atop Stone Mountain was in August 2017, the same month as the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. That permit was denied. In 2022, Georgians can elect Stacey Abrams as Governor and choose Renitta Shannon as Lieutenant Governor. Electing two African American women to top leadership in a state with such a sordid history around race and white supremacy will be a colossal achievement. In addition, we can select Georgia State House member, and daughter of Vietnamese refugees, Bee Nguyen as our next Secretary of State. And we can also choose gay State House member Matthew Wilson as our next Insurance Commissioner. I look forward to the day when electing someone of a particular gender, race, religion, or sexual orientation doesn’t signify a great advancement in our society. Until then, I’ll mark these candidacies and their political wins as monuments—monuments that signify progress for the entire human race. *Fair Fight works to register voters and protect voting rights across the United States. To learn more or get involved, visit https://fairfight.com/

I’m old. And I’ve recently decided that aging after 60 is exponential: each day I age feels like a hundred; sometimes a thousand. When I was 59, I was doing OK. A few years later, and I hardly recognize myself. Not that long ago I was a competitive triathlete and runner. Then work and injuries—and a pandemic—got in the way. I hung up my sneakers and decided it was time to give it a rest. But today I took a leap of faith. I ran a 10K race, my first since 2018. As I analyzed what possessed me to throw good money at such insanity, I settled on three things: 1) I whole-heartedly support the work of the Kentucky Historical Society Foundation, which was the beneficiary of a portion of the race fee; 2) Running in downtown Frankfort, Ky., is challenging and full of distracting and visually arresting historical landmarks; 3) I wanted to see if I could. After a night of torrential downpours, it was a startlingly beautiful morning: sunny and cool (around 52 degrees), with the clearest sky we’ve seen in days. That alone gave me an edge, after running through the prolonged summer’s heat and humidity. I had convinced myself to take it easy, go at my training pace, and not try to keep up with my former competitors. Frankfort sits astride the Kentucky River, and the city’s hills and bluffs offer challenging terrain. We started downtown at the Thomas D. Clark Center for Kentucky History, ran along Broadway where railroad tracks bisect the street in front of the old Greek Revival capitol building, traveled back down Main Street and up Capital Avenue to circle behind the new capitol, then returned to Main Street. At that point, your stomach knots. As we turned east, we headed straight up a nearly half-mile hill past the old arsenal to the historic and exceptionally scenic Frankfort Cemetery, the final resting place of Daniel Boone. The hilly path through the cemetery offers a breath-taking vista of the city and the river below. After turning back toward the entrance, we encountered a lone drummer and cornet player in Revolutionary War garb playing period music. The smile on my face was as broad as the river, and my pace quickened. Once we exited the cemetery gate, it was a fast downhill back into town and around to the finish line. I had a good race, exceeding all my expectations. Although I’m decidedly slower than I was in 2018, I felt at ease remembering what it’s like to push my body beyond what I think it’s capable of doing. And even this cranky old body cooperated. For nearly an hour I did not think about any of the sources of the summer’s sorrow and grief. I concentrated on my breathing, on the sights around me, and on chatting briefly with other runners along the course. For a few minutes, I was a kid again racing ahead of all the adult troubles sneaking up behind me.

|

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed