Fairfax Hall in Waynesboro, Va. Fairfax Hall in Waynesboro, Va. When I was 15, I attended a boarding school in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. How I ended up there is a long story, and I won’t bore you with that. But I was attracted to the school largely because its beautiful old building—originally a Queen Anne style wood-shingled resort hotel--was butted up against a mountain. In addition, one of the school’s most renowned features was its equestrian program, which prepared well-heeled young ladies for the pageantry and horsemanship of local fox hunts. Like most girls my age, I was a horse enthusiast. I had attended summer camps where I learned to ride and care for horses. I had even tried a little “hunt seat equitation,” learning to coax those thousand-pound athletes over a variety of fences. I was tiny, however, and although very little scared me, that did. So, after arriving at boarding school, I quickly realized the riders there were out of my league, in more ways than one. I was more drawn to the mountains anyway. I signed up for every canoe outing, every hike. I rode my bike over to Staunton. I played a lot of tennis on the school’s courts, partially to soak in the view of the mountain at the edge of campus. I reveled in the heavy snowfalls in the winter. It was year-round camp, with a healthy dose of academics on the side. Since then, I have harbored an affinity for mountains that is hard for me to explain. I was born in a city, spent my early years in another East coast city, and came to maturity in a small town in central Kentucky, far from any mighty peaks. But I crave spending time in the mountains. I heave a deep sign of contentment the minute I see the mountains looming as we drive east toward the Appalachians. In the novel I just completed, I describe how Effie Mae feels as she leaves the looming mountains of Bell County for the first time. To capture her thoughts, I relied on the visceral sadness I experience when we drive home toward the Bluegrass. While in New England recently, we made a short side trip to Mt. Greylock, the tallest mountain in Massachusetts at nearly 3,500 feet. From its summit, you can see mountain ranges in at least four states. That, indeed, is heaven for me. We had time to hike a rugged loop trail part-way down the mountain and back up, briefly segueing with the Appalachian Trail. I was happy. I don’t know if you can inherit a love of the outdoors or a near-physical need to be in the woods. But after recently reviewing scores of photos of my dad in the field mapping the trees of our eastern forests, I have to believe it’s possible. How I regret never being able to walk the woods with him, learning a tiny portion of what he knew. How fortunate I am to have this time in my life—that he never did—to leisurely explore the quiet majesty of those mountains, before human indifference threatens their very existence. After visiting Mt. Greylock, Henry David Thoreau wrote the following (which is engraved in a stone on the mountain’s summit):

"As the light increased I discovered around me an ocean of mist, which by chance reached up to exactly the base of the tower, and shut out every vestige of the earth, while I was left floating on this fragment of the wreck of the world."

5 Comments

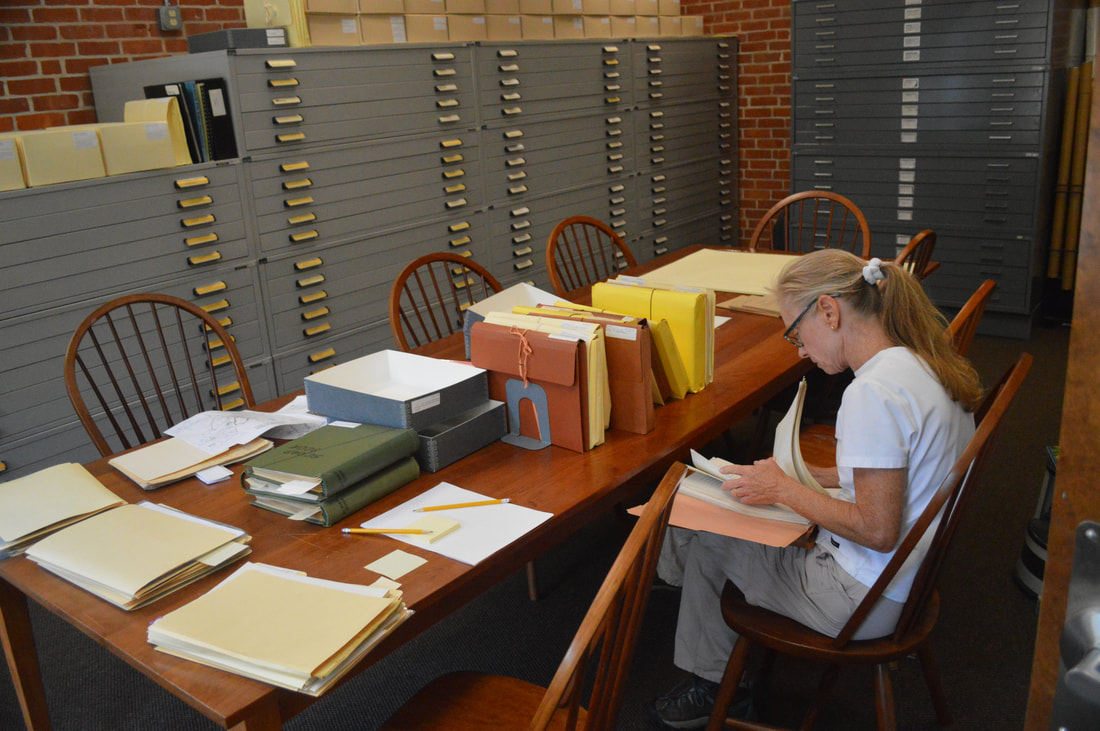

Photos by Rick Showalter. Photos by Rick Showalter. When I first saw the sign, I snickered. I’ve been traveling a lot this summer—long days in a car, routines upended, meals eaten out—and I’m definitely more “thickly settled” than I’ve been in a while. That’s common for someone my age, I suppose. But the unexpected sign seemed a mocking public rebuke. Of course, the sign was warning us of the population density outside Athol, Massachusetts. Here in Kentucky—a rural state by all accounts—we’re more accustomed to seeing “Congested Area” signs when a curve in the road reveals a cluster of homes or other indications of human activity. Perhaps New Englanders adopted their expression back in the mid-1700s, when most of these towns were established. A few moments later, as we approached the iconic New England village of Petersham, there stood another “Thickly Settled” sign. I could count three or four houses dotting the rim of the beautiful town common, a gathering place for all 1,200 people who live there. The expanding roll around my middle, I thought, is denser. By all appearances, Petersham hasn’t changed since the 1950s, when my family lived there. The Unitarian church is still at the center of the green, with the handsome stone library just a couple of doors down. Across the common, the general store still serves the residents, although the current proprietor is more interested in selling you healthy snacks than the cigarettes I remember buying there for my mother when we visited some years after moving away. The town hall is next door. And in the middle of the common is the obligatory bandstand, where we enjoyed a concert by the Petersham Band on Sunday evening. The closest gas station? Fifteen minutes north or south of town. Harvard Forest, the 4,000-acre research forest where my dad worked, is just down the road. We were in Petersham to meet with the director of the Forest, David Foster, who had invited us to review the voluminous materials relating to my father’s work currently housed in their archives. Julie Hall, Harvard Forest archives assistant, had covered a long cherry conference table with sleeves of photos, scrapbooks, published materials, bulging pocket folders of research notes and presentations, and correspondence between my dad and other staff scientists. I couldn’t hold back a few tears as I surveyed the treasures on the table and considered the painstaking care of the archivists who had stored these materials for nearly 70 years. I settled in at the table and consumed as much as I could in the few hours I had. Then we headed back outside to walk through the surrounding woods, the target of much of the research ongoing at the Forest. I discovered that Prospect Hill Road—a path my father frequently mentions in the journal he kept while at the Forest—is not a road at all, at least in our lifetimes, but a 2.5-mile loop trail through the forest, passing tagged trees and research equipment. We walked amid beeches, oaks, pines, and maples; dense ferns nearly disguising stone walls built by early settlers; twisted trees that survived the 1938 hurricane; hemlocks severely threatened by the woolly adelgid; 300- and 400-year-old black gums in a swamp area. It is a gorgeously diverse woodland. Back at the parking lot in front of Shaler Hall—the red brick office and classroom building named for Kentucky’s own Nathaniel Southgate Shaler—I looked around one more time at the buildings and the land so familiar to my parents so many years ago. As a young couple hoping to start a family and build a career far from their Kentucky home, my parents faced many challenges while in Petersham. But the area evokes a sort of nostalgia for me. My dad still has a presence there. The people welcome us as if we naturally belong. The woods beckon. In town and at the Forest it’s as if time has stood still, even if my graying hair and growing girth attest otherwise. For an up-close view of the work going on at Harvard Forest and how scientists there are striving to measure the toll of climate change, I highly recommend Witness Tree by Seattle environmental reporter Lynda V. Mapes. You can watch the daily changes in the 100-year-old red oak she observed for more than a year by accessing the Harvard Forest webcams here. Scroll to the bottom of the page for a view of Mapes’ witness tree.

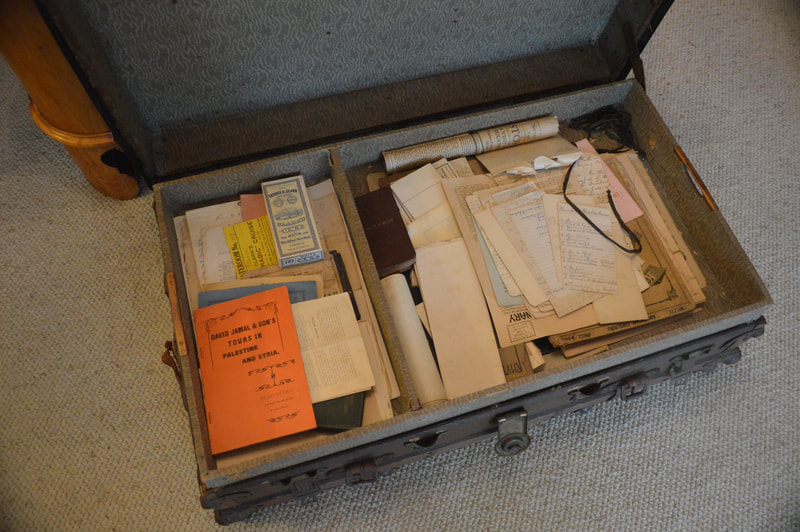

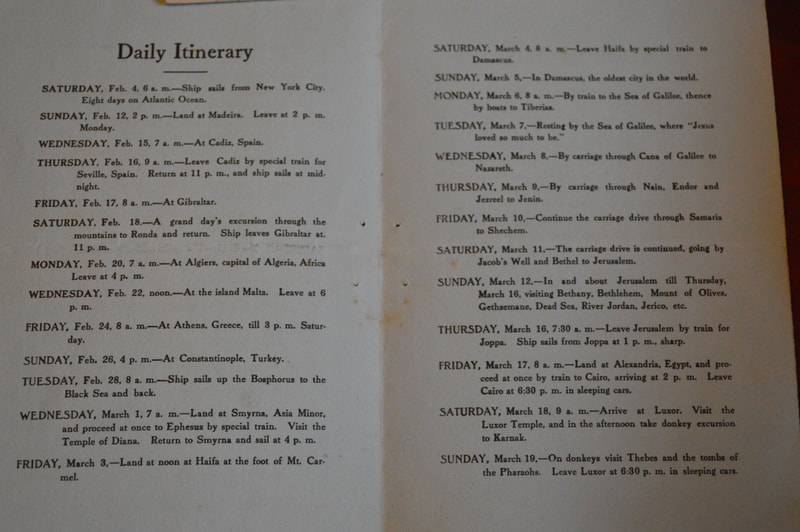

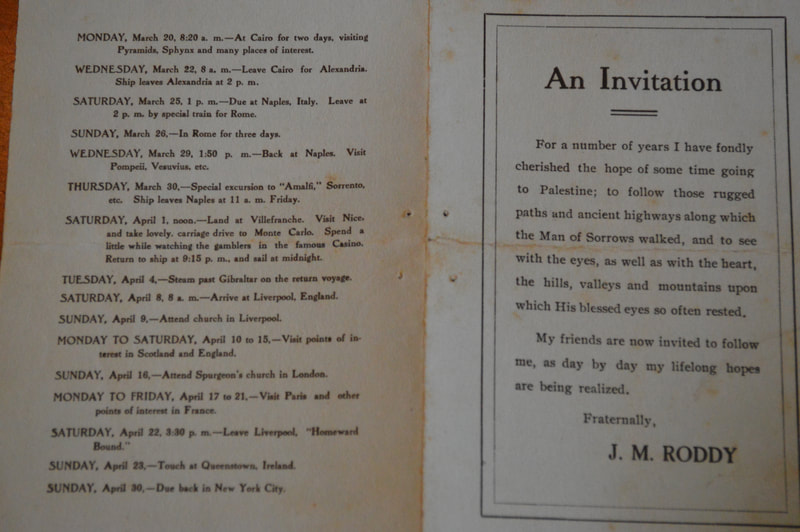

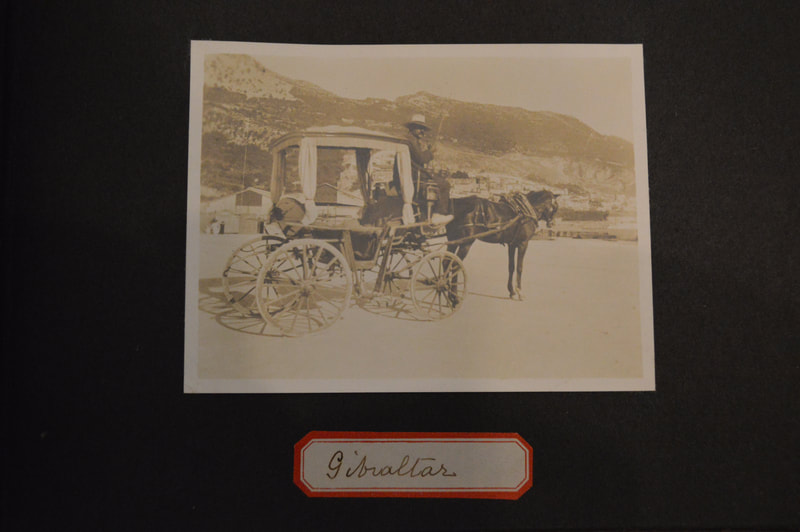

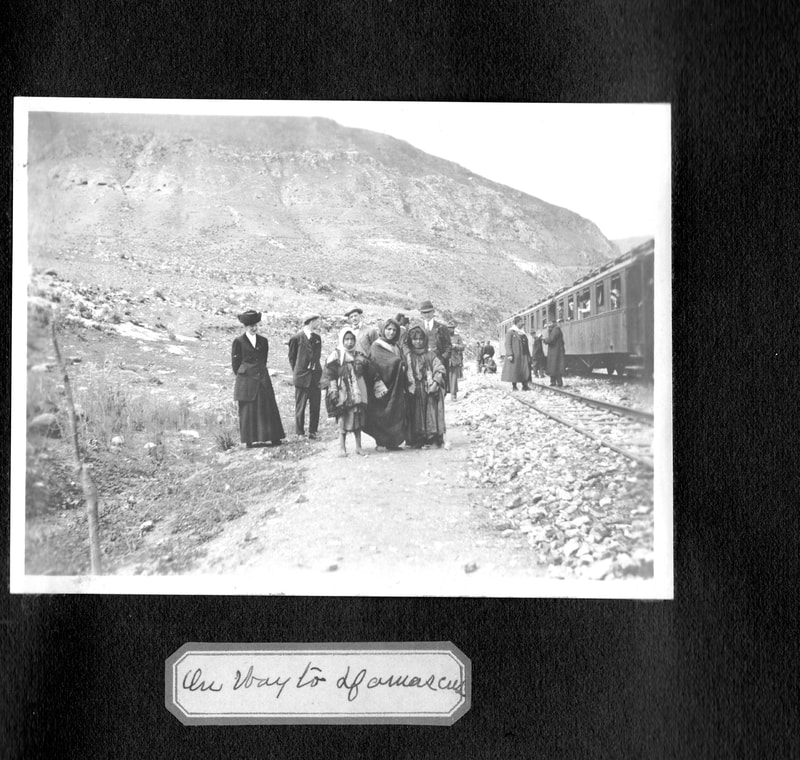

It’s like a geode I’ve successfully cracked open but haven’t yet had the chance to examine. It’s waiting there expectantly, with all its sparkling treasure, this ancient trunk with its broken clasps and brittle leather straps. It arrived yesterday, a mysterious portmanteau that holds within its confines the length and breadth of my great-grandfather’s restless mind and peripatetic wanderings: the sermons outlined, the teachers certified, the schools visited, the marriages performed, the eulogies delivered, the newspaper articles written, the farm business documented. His journal from 1876. Notebooks from his Georgetown College days that include Greek and Latin translations, advanced math, and notes about his roommates’ romances. The camera he took to Europe and the Holy Land in 1911. The pebbles collected from around the world. The 1920 registration card for “Old Danger,” the Ford he never drove. Sheet music and a piano method book. Virtuoso panegyrics to exotic lands. All of Bro. W. D. Moore’s extraordinary life seems compressed in this chest. Photos, letters, postcards, itineraries, sermons, ledgers. I’m itching to dig through it, to read every one of the letters and finger each artifact, trying to imagine his life. It may take my lifetime to look through it all. But it’s beckoning me to set aside my plans, ignore my commitments and kneel before this sarcophagus that holds another man’s secrets. What could possibly be more interesting? Or more important?

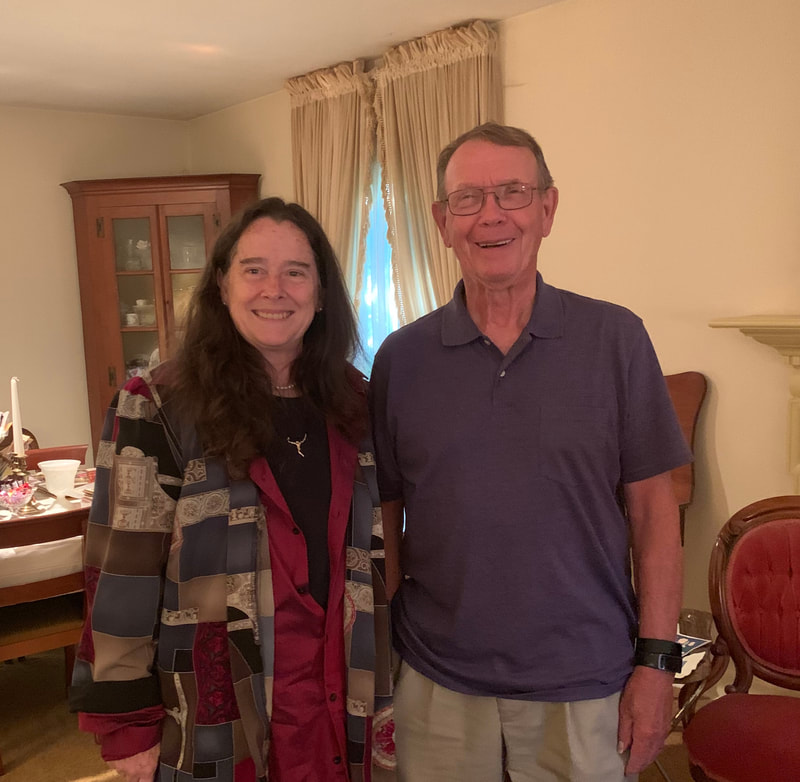

But, alas, it has to wait. I’m off on another adventure of my own, seeking to learn more about Dudley’s grandson, Martha’s youngest boy, my father. When I return from that journey, I’ll carve out the time to dive into this treasure chest and immerse myself in the minutiae of an uncommon life, a life that spanned nearly 80 years more than 100 years ago. The trunk arrived after a curiously circuitous journey, after having been lost to the family for a number of years. I had no idea it even existed until a few months ago. It evidently has landed in my home now because others believe I have room to keep it—or, rather, that I will keep it safe. Or perhaps they know I’m a sucker for historical family documents. Whatever it’s tortuous path, it’s here now, for a stay of uncertain duration. Anyone interested is welcome to come visit and pan for gold. As I’m able, I’ll share items from its contents that I think might interest you. Let me tease you with one of my favorites: a rare informal photo of the respected and beloved itinerant preacher.  A very young Pud Goodlett protectively embraces his cousin Jane Moore, circa 1926. Photo from the collection of Jane Moore McKinney. A very young Pud Goodlett protectively embraces his cousin Jane Moore, circa 1926. Photo from the collection of Jane Moore McKinney. “I can’t believe those two boys built that cabin all by themselves.” And with those words I discovered one more among us who still remembers Camp Last Resort along Salt River. On Saturday I had the privilege of chatting at length with another of my dad’s first cousins: Jane Moore McKinney, the older sister of John Allen Moore to whom I dedicated the book. At age 96, her smile lights up the room and she demonstrates the same knack for storytelling as her two brothers. Her memories are clear and precise and she is a delightful conversationalist, even though challenged by encroaching deafness. Her grammar is impeccable, reflecting the education she received as a young girl at an Atlanta academy associated with Emory University (her father worked for the railroad at the time). For example, my editor’s ear perked up when I heard her say, “He was seven years older than I…”  Photos from our visit all courtesy of Bob Goodlett. Photos from our visit all courtesy of Bob Goodlett. She talked of our Aunt Sallie hauling heavy containers of milk from Grandpa Moore’s milking barn to the road to be picked up by a truck from the cheese factory in Lawrenceburg. She described how her future husband, stationed at a Navy facility outside Atlanta during World War II, leaned out of a passing streetcar madly calling her name as she stood along Peachtree Street. (She had met him once before. Click here to listen to her relay that scene.) She described life in 1940s boarding houses and sharing a bathroom with four other couples. I learned that before her marriage she had dated my mother’s cousin—and my father’s friend and classmate—George McWilliams, whom she spoke of repeatedly and fondly. When I talked to her on the phone about a month earlier, using a TTY device, she assured me drolly, “I inherited the deafness: It wasn’t something stupid I did.” She wanted to be sure we knew she had been driving and attending her weekly supper parties just a couple of years ago. Spending time with her this weekend, I have no doubt she charmed everyone at those gatherings. Now, frustrated by having to rely on a wheelchair, she seems bewildered that her body has begun to bow to age. I had met Jane briefly at a couple of family funerals. I knew she was fond of my dad. But, inexplicably, I had never made the short trip to Owensboro to get to know her or her children. So the traveling trio of Goodletts—my cousins Sandy and Bob and I—arranged a brief visit with Jane, her daughter Jane Allen, and her son Jim. This is the legacy of publishing The Last Resort. By delving a bit into my father’s story, I have been inspired to spend time with family I hardly knew. I am getting to know John Allen’s family and Jane’s family, and I have visited their brother Joe and his wife, Jean, who rescued me when I was a lost high school student in Atlanta years ago. I have spent hours talking to two of my first cousins as we traveled across the South—two cousins who had launched their careers by the time I was a child settling back in Kentucky after my father’s death. I look for reasons to get in touch with my McWilliams cousins, my Hanks cousins, and my Birdwhistell cousins. And I am delighted by all my interactions with them. Unexpectedly, I am finding family and family connections endlessly fascinating. I wish I had had the impetus long ago to reach out to them. As one of the youngest of my generation, I think I was mildly intimidated by all my interesting older cousins. But I’m glad I rounded up the courage to push myself into their lives in some small way. And I am deeply grateful for the opportunities to get to know them.  Jane's daughter, Jane Allen McKinney, is a nationally recognized artist. Her immense sculpture, towering over the Tennessee State University Olympic Plaza, is constructed of metals representing the actual percentage of gold, silver, and bronze medals the university's athletes have been awarded. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed