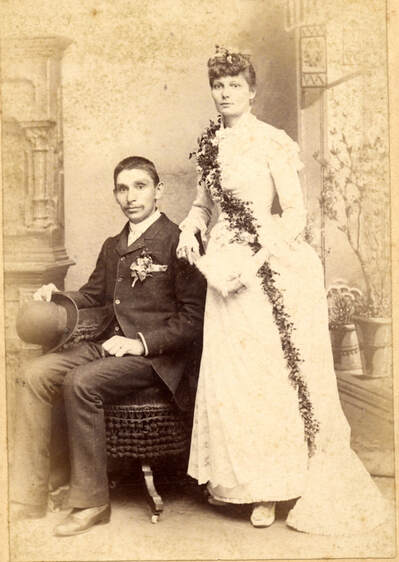

Peggy's family preserved this photograph, but the identity of the couple has been lost to time. Peggy's family preserved this photograph, but the identity of the couple has been lost to time. Peggy Cooper, of northern Kentucky, is the co-editor of Celebrate a Community, soon to be reprinted by Murky Press. Celebrate a Community began as a group project. It grew out of an effort to celebrate the Sesquicentennial of Fayetteville, Ohio. Fifty years before, my co-editor, Harold Showalter, had organized the Centennial Celebration of this small rural community. That celebration was a powerful influence on many of us younger folks. Suddenly, fifty years later, we were the generation that would decide if our community’s history was still important enough to commemorate and remember. My brother-in-law asked a few weeks ago why all of these old stories are important. He couldn’t see any value in things said and done long ago. I mumbled some response that would convince no one of the importance of the task. Having had a chance to consider the question, I would now ask if he would mind being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s dementia. Of course he would! None of us would choose such a disease—death, a little bit at a time, as our memories and all that is important and meaningful slips away forever. Communities can suffer from a kind of Alzheimer’s, too, and the effect is just as devastating for the stricken community as it is for the stricken individual. Remembering is important to who we are, as individuals or as a society. Sadly, the importance of history often goes unrecognized until it is too late to claim it. I am proud to have been a part of the effort to preserve our sense of community.

0 Comments

The pencil holder on my office desk says it all. The pencil holder on my office desk says it all. I typically like detail work. I like precision. My eye is trained to see tiny variations in a pattern or errors that others might skip over. That doesn’t mean I don’t sometimes miss things or get things wrong. But I’m accustomed to settling down and doing careful, painstaking work. I have to confess, however, that there have been times recently when I was ready to raise my hands in surrender as I have worked through the final intensive edits of my novel. I know how critically important this phase of writing is. I usually relish the final polishing. But after three rounds, I am exhausted. Before I say more about that, however, let me first say how deeply indebted I am to the editors and readers who pored over the manuscript and alerted me to issues that, without correction, would have embarrassed me or confused readers. There is no question the book will be better because of their efforts. But back to my numbing fatigue. I have written before about how writing is an infinite series of decisions: choosing the next conflict, the next scene, the next setting, the characters’ reactions, the syntax of the next sentence, the next word, a better word, and punctuation that is both consistent with convention and imbues the rhythm and music—and meaning—that you want to convey. For someone who hates making decisions (that would be me), it can be torture. In this late stage of the novel-writing process, everything is a decision. An edited page that appears to have two simple markups takes 30 minutes to revise. Shall I take that comma out or leave it in? Grammar rules say it’s acceptable, but the short clauses make it optional. Does it change the emphasis if I remove it? Does it change the rhythm? Why did this editor suggest taking it out? Read it with the comma. Read it without the comma. Repeat. One more time. Which option relays what I’m trying to say? Will any reader ever give a damn? Is it time to walk Lucy? Chicago Manual Style or AP Style? Arabic numerals or all numbers spelled out? Spaces between the dots in an ellipsis or use of the ellipsis symbol? And the comment I now dread the most: Is this phrase too modern? Since I started putting words on the page three years ago, I’ve recognized the importance of getting the language right. The bulk of the novel is set between 1921 and 1942. I wish I had a dollar for every phrase I have looked up to see when it came into the lexicon. “Pratfall”? “Down payment”? “Hang with”? “Have my back?” Even with the convenience of the Internet, those searches take time. Once I’m satisfied that the words on the page are the best they can be, there’s the book design to consider. A few weeks ago, I told an interested party that I was starting the page layout process. It was clear that she couldn’t imagine the decisions that requires. A novel has a simple layout, so even I thought that part of the project would be relatively straightforward. But I found a way to agonize over the font size, the line spacing, the margin size, the Table of Contents. Tonight, however, I am celebrating. I am done. I’ll request one final proof. Complete one final read-through. Pray that any remaining issues are tiny and easily remediable. But, mostly, pray that I find them before my careful readers do!  My side yard: A future rice paddy? My side yard: A future rice paddy? “We’re living in a terrarium.” Those were the first words I heard as I stumbled downstairs in the perpetually dark mid-morning gloom. Even my husband was beginning to feel the oppressiveness of the weather. We hadn’t seen the sun in weeks. Heavy rain had turned our yard into an Ichthus-like mud pit. The small lake abutting our property looked like the Mighty Ohio. I contemplated terracing my side yard into a working rice field. With stubborn, heavy clouds trapping the persistent rain, it did indeed feel like living in a glass-cased terrarium. The abundant moisture condensed, fell, partially evaporated, and condensed again. There seemed to be no escape from the cycle. We, fortunately, are not facing the critical, life-threatening flooding of other parts of Kentucky and the South. But my mood and my productivity have suffered during the most depressing winter I can remember. We’ve only had a handful of days where the overnight temperature dipped below freezing and the ground was even partially frozen. Walking the dog across the flooded fields in our neighborhood was, I imagined, like sloshing through a rice paddy. I wash piles of muddy dog towels every other day. The weatherman, however, says there is hope. Tomorrow, perhaps, for the first time since February 2, we may glimpse the sun. According to my running log, the last sun before that was on January 16. No wonder I’ve been suffering. With partial vision loss, my days start off dark. When there is no natural light, I fall into an abyss. A friend recently sent me an unfamiliar word I have now embraced: apricity. It means “the warmth of the winter sun.” Evidently the word was first introduced to our language in 1623, but it didn’t catch on. Today you won't find it in most dictionaries. But apricity is precisely what I’ve been craving for weeks. I’m almost giddy at the thought of it. The word also reminded me of a scene in Next Train Out. Effie Mae is living with her children and her brother in a godforsaken coal camp west of Middlesboro, Ky. One day when she’s out and about she sees an unfamiliar man who ends up playing a key role in her life: “It was late March, as I recall, and the sun had finally risen above the Cumberland Mountains. I found a spot in the sun’s warmth and just stood there, staring at the door he had entered. I don’t remember having no clear intentions. It was as if I was hypnotized by the warmth and the sight of a stranger.” A little sun warms our blood and renews our life force. It gives us hope. It softens our hard edges. It prompts us to act. It may not solve all our ills, but it might provide the energy we need to renew the fight. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed