Cicada crash. That’s an empty flask of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky you see. Some of these characters had a little too much fun. Photos by David Hoefer. Cicada crash. That’s an empty flask of Fireball Cinnamon Whisky you see. Some of these characters had a little too much fun. Photos by David Hoefer. David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, bids a fond farewell to the Brood X cicadas. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. The cicada bloom is finally starting to wind down in my neck of the woods (which is the Louisville Highlands). It is increasingly possible to hold an intelligible conversation with another human outside the house and to travel the sidewalks without the regular crunch of dead or dying bugs underfoot. That said, I had a final cicada experience that might be worth relating. I’m currently taking an online birding course through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (an organization whose praises I’ve sung previously on this blog). One of the exercises, called “sit-spotting,” involves sitting outdoors for 15 minutes, observing the immediate surroundings, and making note in a field journal of all that which most impinges on the five senses. In a Kentucky suburban environment, that ought to mean birds, squirrels, chipmunks, bees, cats, breezes, floral scents, etc. I did this a couple of weeks back, when the cicadas were still hot and heavy. Not wise. My entries read something like:

I’ll give the cicadas this: every 17 years they put on what is truly a command performance. I guess part of the diversity of nature that we always go on about, is that sometimes there is very little diversity at all.

4 Comments

John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett with his beautiful bride, Mary Marrs Board, December 27, 1947. John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett with his beautiful bride, Mary Marrs Board, December 27, 1947. I’ve never liked Father’s Day. My father died unexpectedly when I was seven, and I’ve felt cheated ever since. I could happily wipe that holiday off my calendar. This year, however, marking Father’s Day is putting a smile on my face. Recently, my cousin Bob Goodlett had some iconic family video digitized to share with relatives near and far. Today, I’m sharing my Father’s Day joy with you. It turns out that my Uncle Leonard Fallis, husband of my dad’s older sister, Virginia, had an 8mm movie camera as early as the 1940s. I don’t recall ever having seen the following clip before Bob shared it with us last month. But there’s my father, before the war and all the horror he witnessed, strutting around his family’s property in Lawrenceburg, Ky., in his University of Kentucky ROTC uniform, being silly, mugging for the camera, while his faithful dog, Mike, gambols at his feet. The youngster at the beginning of the clip is my dad’s nephew Robert Dudley “Sandy” Goodlett, who died April 26, 2021. Readers of The Last Resort may remember references to “Sweetpea” visiting the boys’ camp. At the end of the clip, you’ll see my dad’s nephew Davy Fallis, aka “Sluggo,” who died March 7, 2018. One of the letters that Pud wrote to Davy and his parents while at basic training in Texas is included in Appendix A of The Last Resort. During a Goodlett family reunion in 1984, I remember being emotionally walloped when one of the Fallises played some of their archival movie footage that, at the time, I had no idea existed. By that summer, my dad had been gone 17 years. Suddenly, on a small screen in a northern Kentucky hotel gathering space, there he was in an intimate, playful moment with my mother, shortly before they were married. I gasped, and then I sobbed. If they played more old footage of either of my parents that evening, I missed it. (That’s Davy Fallis again, chaperoning the scene.) In the following clip, that footage is preceded by images shot on their wedding day, December 27, 1947. Lawrenceburg natives may recognize several in the wedding party: Lin Morgan Mountjoy, Bobby Cole, George McWilliams Sr., George McWilliams Jr., Vincent Goodlett, Ann McWilliams, Mary Jane Ripy, Ann Dowling, and Madison Bowmer (of Louisville). In this era of cell phones and selfies and images and video shared instantly with the world, it may be hard to imagine what it means to me to have this rare video of my dad. I have only a few memories of him from my childhood. So seeing him move—his mannerisms and his interactions with others—makes him real. It confirms what others have told me in recent years about his sense of humor and how much fun he was to be around. And, of course, it confirms all that I missed by losing him at such a young age. I am deeply grateful to Vince Fallis for preserving the original 8mm reels for more than 70 years and to Bob for making the video more widely available. This Father’s Day, I am thinking about playful Pud, and I am having a good day. The only other video of Pud that I’m aware of was shared with me by Bob Cole, Bobby Cole’s son. Appropriately, my dad is fishing. You can watch it here.

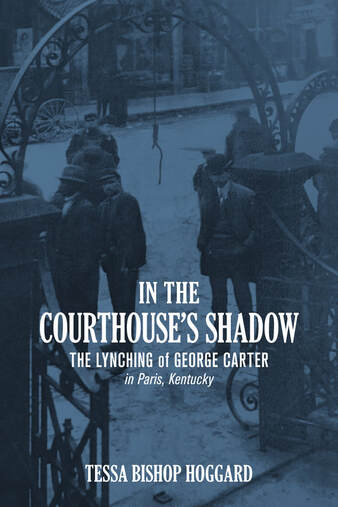

The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. As I started working on Next Train Out, I knew that racial conflict had to be a theme of the novel. It seemed clear to me that the trajectory of Lyons Board’s life had to be predicated in part on his role, as an eight-year-old boy, in having a Black man lynched in his hometown, Paris, Ky., in 1901. As I researched the various cities and towns where my grandfather eventually lived, I found plenty of instances of racial unrest in their histories: mob violence, riots, lynchings, the obliteration of sections of towns where Blacks lived and prospered. Soon I began to better grasp the bigger picture, that the whole country was awash in deadly racial conflict just after World War I, when Black soldiers returned home expecting opportunities and respect in return for serving their country in the trenches in Europe. Instead, they found resentment and violence stoked by the belief among some white citizens that these returning veterans threatened their jobs and their status in the community. I learned about the Red Summer of 1919, which made me realize how widespread these race problems were. These confrontations were not isolated to the Deep South. They erupted in our nation’s capital, in Chicago, in New York and Omaha—in at least 60 locations from Arizona to Connecticut. How this anger and suspicion manifested itself in towns like Corbin, Ky., and Springfield, Ohio, are part of Lyons’ story. As we all now know, an area referred to as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Okla., waited until 1921 for its turn at center stage. On June 1, after 16 hours of horror, more than a thousand homes and scores of businesses had been incinerated. Somewhere between 100 and 300 people had been murdered. Thousands of Black survivors were then corralled into a detention camp of sorts and assigned forced labor cleaning up the mess the violent white mob had created. Before June 2020, when President Trump landed in Tulsa for a campaign rally originally scheduled to take place on Juneteenth, few Americans knew the lurid history of Black Wall Street. The facts had been suppressed, kept out of classrooms, out of the news, out of polite conversation. Black families in Tulsa passed down stories of violence and terror and escape—or stories of family members never seen again, their fates unknown. Few public officials dared recognize what had happened to all those people and their livelihoods and their property and their wealth. This year, on its 100th anniversary, the entire nation has been awakened to Tulsa’s tragic history. LeBron James produced a documentary—one of many. Tom Hanks wrote an op-ed. HBO made its Watchmen series accessible to more viewers. News forums of all types reported on the anniversary. Survivors of the massacre—all more than 100 years old--testified before Congress and met with President Biden. Under the leadership of Tulsa’s young white Republican mayor, G. T. Bynum, archaeologists have resumed the search for mass graves that had finally begun last summer. How a community like Tulsa now, finally, begins to reckon with its history is significant for all of us. We as a nation, as a collection of human beings, must break the silence we have permitted ourselves for generations and acknowledge how gravely we have wronged indigenous peoples, Blacks, and other minorities. How we blithely destroyed their culture, their history, their identities, and their lives. Acknowledging the truth is a start. Reporting historical facts is essential. Engaging in respectful, compassionate, and sensible discussion can prompt healing. Some communities—and even the U.S. Congress—are now beginning to discuss what reparations might look like. Other communities first need to simply acknowledge both the shame and the pain that have churned for decades among their citizens. When I first met with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of the man lynched because of an alleged incident with my great-grandmother, he made it clear that it was the silence that weighed most heavily on him. He had tried to learn more about the lynching of George Carter, but no one would talk about it. His elders wouldn’t talk about it. The Black community wouldn’t talk about it. Fear and shame and ongoing oppression had kept everyone close-mouthed for generations. The emotional damage accrued. The human damage. The not knowing. The not understanding.  With her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow, Tessa Bishop Hoggard provided the key that Jim needed to open the door to his family’s history. She pulled his story out of the shadows. Jim has told me repeatedly that he feels an extra spring in his step now that he knows the facts. He has found a peace that had eluded him all of his eighty years. In her interview with Tom Martin on WEKU’s Eastern Standard program this week, Tessa said, “As we peer into our history, hate crimes were a common daily occurrence….Accountability and consequences were absent. There was only silence. This silence is a form of complicity….Today is the time for acknowledgment and healing. Let the healing begin.” (Listen to the 10-minute interview.) We have to acknowledge our difficult history. We have to face what happened. And then we have to consider the steps, both small and large, that we can take to heal the wounds that will only continue to fester if we stubbornly ignore them.  This year, on the morning of Juneteenth (Saturday, June 19), I’ll have copies of Tessa’s book and my novel available for sale at the Lexington Farmers Market at Tandy Centennial Park and Pavilion in downtown Lexington, Ky. In August 2020, the citizens of Lexington agreed to rename Cheapside Park, the city’s nineteenth-century slave auction block and one of the largest slave markets in the South, the Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park, honoring the freed slave who did masonry work for many of Lexington’s landmarks, including laying the brick for the nearby historic Fayette County courthouse, built in 1899. One of the organizers of the “Take Back Cheapside” campaign, DeBraun Thomas, said at the time: “Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park is one of the first of many steps towards healing and reconciliation.” Fittingly, I’ll be at the Farmers Market as part of the Carnegie Center’s Homegrown Authors program. Tandy had a hand in the construction of Lexington’s beautiful neoclassical Carnegie Library on West Second Street in 1906, now the home of the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning. If you’re in Lexington that morning, stop by and we can continue this conversation.  The Brood X cicada is descending on the eastern U.S., from Illinois to New York and south to Georgia. Photos by David Hoefer. The Brood X cicada is descending on the eastern U.S., from Illinois to New York and south to Georgia. Photos by David Hoefer. David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, examines our latest plague. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. They’re here. In fact, they’re everywhere—gazillions of them. They’ve come up from holes in the ground, where they spent 17 years sucking nutrients from plant roots in the dark, biding their time until nature called them to invasion. With their cellophane wings and bulbous red eyes they look like something out of an Old Testament plague or maybe next-of-kin to the “Bug-eyed Monsters” (BEMs) that infested the covers of science-fiction pulp magazines from mid-20th century America. And the racket—an incessant loud thrumming from high in the air, as though alien spacecraft were massing behind tree cover or Saruman the White was working up his war engines, as described by Tolkien in The Lord of the Rings. Reportedly, that racket can raise noise levels in neighborhoods up to 100 decibels. What am I going on about? Why the 2021 vintage of Brood X cicadas, of course. You likely know the story by now. Brood X is number ten of 15 groups of periodical cicadas resident in eastern North America. It consists of three species and is the largest and most widespread of its kind. Brood X nymphs tunnel up from their underground lairs every 17 years, once soil temperatures reach 64 degrees Fahrenheit. They shed their exoskeletons, briefly taking on a final adult form. What follows is a furious few weeks of them discharging their Darwinian duty—flying, mating, laying eggs in the trees, and dying. And, yes, all that noisemaking—the male’s monochromatic version of a mating song. Brood X cicadas are estimated to emerge in the trillions, and species survival depends on it, because these defenseless insects make easy prey for a variety of birds and other hungry creatures (including my dog, who wolfs them down like a human chomping on potato chips—a protein supplement, I suppose). In the meantime, cicadas are as common as hydrogen, and getting into everything. You name it and they‘re on it—clothing, hair, cars, furniture, rugs, sidewalks, houses, and every other manifestation of human culture. Their weird insect noises and alien ugliness make them unwanted guests, but the fact is, unlike last year’s virus, they’re perfectly harmless. Brood X cicadas may be the ultimate proving ground for the philosophical notion of “live and let live.” Kentucky is not actually at the epicenter of Brood X, but the bugs are certainly present and accounted for in the Bluegrass State (including in great numbers in my treelined yard). Entomologists see this North American version of a locust visitation in effect until mid-July, when the survivors will begin a new 17-year cycle of root-sucking and apocalyptic emergence and transformation. The best we can do for now is batten down the hatches and learn to live with one of nature’s stranger life utterances. If you’re inclined toward more active observation, I can suggest an interesting application that is downloadable to iPhone and Android devices. Developed by an academic at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati and called Cicada Safari, it enables Joe and Josephine Test-tube to take on a citizen-scientist role during the Brood X interval by documenting local cicada activity with photographs and videos and posting them to an ever-growing database curated by the application’s sponsors. I’ve enjoyed running around my neighborhood looking for interesting shots, once I got over my initial repulsion. Just remember: the cicadas probably find us at least as hideous to contemplate. AddendumThere is no mention of cicadas in The Last Resort, which makes me think that John Goodlett didn’t observe them in the Lawrenceburg environs during 1942-43. Brood X outbreaks would have occurred in 1936 and 1953, outside of the journal’s timespan. But there are other broods on different schedules, waiting for long periods to climb into the light and then share the world with us, if only briefly.

|

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed