Katlin Roberts, right, the Bourbon County winner of the conservation essay contest. Katlin Roberts, right, the Bourbon County winner of the conservation essay contest. One of the unexpected joys (or terrors, depending on when you ask me) of having published The Last Resort has been the opportunity to talk about the book to various civic or environmental groups. On Tuesday, I spoke to nearly a hundred farmers and civic leaders in Paris, Ky., at the Bourbon County Conservation District’s 60th Annual Dinner Meeting. The food, prepared by a men’s group at the Church of the Annunciation, was outstanding and the crowd was friendly and welcoming. I was honored to donate a generous honorarium for my presentation to the Woods & Waters Land Trust, an organization dedicated to protecting forests and streams in the Lower Kentucky River watershed. The theme for the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources’ annual essay and art contests, sponsored by the local conservation districts, was “Diggin’ It”: soil as the foundation of life. I had little trouble connecting that theme to my father’s love of the rural central Kentucky land and his collaborative research with soil scientists and geologists later in his career. A quote from one of his contemporaries, which was included in the event brochure, summed up the focus of the evening: “Essentially, all life depends upon the soil…There can be no life without soil and no soil without life; they have evolved together.” –Charles E. Kellogg, third Chief of the USDA’s Bureau of Chemistry and Soils, 1938 A presentation last October before the Anderson County Historical Society led to another unexpected invitation: putting together an exhibit about my family history at the newly refurbished Anderson County History Museum. I spent a good deal of time this spring talking with family members and collecting photographs and other memorabilia for the display. It has been exciting to work on a project that connected my father’s side of the family—featured in The Last Resort—with my mother’s side of the family—featured in the novel (tentatively titled Next Train Out) that I’m about to wrap up. In the photos below, the portraits on the wall are of George Dennis McWilliams Sr. (1893-1982) and Mary Marrs McWilliams (1894-1977), my great uncle and aunt. The exhibit will be on display from April 2 through at least the end of the month. If you can find an excuse to travel to downtown Lawrenceburg, I hope you’ll stop by and take a look. We’ve left a notebook there for you to record your comments, insights, or any family stories of your own you’d like to share.

Anderson County History Museum 108 East Woodford Street Lawrenceburg, KY 40324 502-598-3127 The museum is inside the Tourism Office, just around the corner from Main St., in the old Carnegie library building (where my grandmother Nell Marrs Board worked for many years). It’s generally open weekdays during regular business hours, but you may want to call before you go. Kendall Clinton, the executive director of the Lawrenceburg/Anderson County tourism commission, may also be able to arrange a weekend visit, upon request.

0 Comments

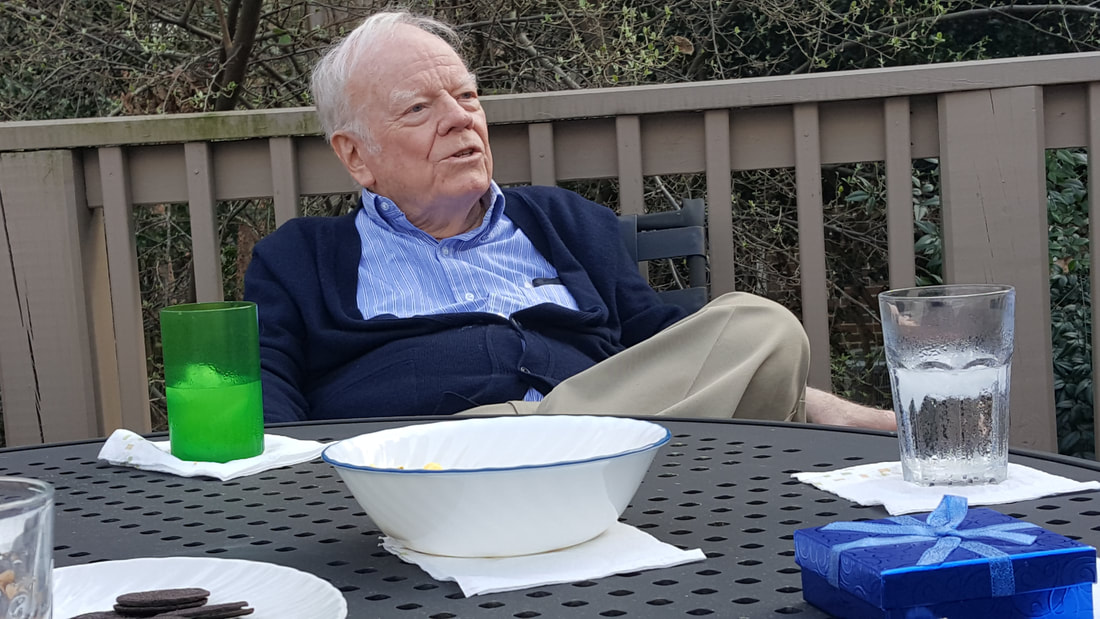

David Foster’s “Thoreau’s Country.” Cover illustration by Abigail Rorer. David Foster’s “Thoreau’s Country.” Cover illustration by Abigail Rorer. Last month I received an unexpected email. I did not recognize the sender’s name, but the email address appeared to be associated with Harvard University. The message began: “I am a tremendous admirer of the work of John Goodlett and had the wonderful experience of having heard stories from many of his close colleagues in Petersham over the 35 years that I have spent at the Harvard Forest. I greatly appreciated reading the journals and the wonderful tributes by Alan Strahler, Sherry Olsen, and Margaret Davis.” I was stunned. Who was this gentleman who, more than 50 years after my father’s death, was still familiar with his work and appeared to recognize his colleagues and students from the 1960s? The letter was signed David Foster, and I quickly searched for more information. I was pleased, and honored, to learn that he is the longtime director of Harvard Forest, located in Petersham, Mass., where my father began his career in plant geography in the 1950s. Thus began a weeklong correspondence of wide-ranging subjects. I learned that Foster worked with and knew well several of my father’s colleagues at the Forest, including some I still remember fondly. I learned that he devoted some time to resurrecting my “father’s maps on oak distribution” and publishing “the map and overview of that classic and unrivaled study.” I learned that he is in the process of digitally archiving much of the Forest’s history and has come across photos and letters and other materials related to my father’s work. I learned, not surprisingly, that he is fascinated by first-person journals and has collected and written about several relating to the land around Harvard Forest and New England. And I learned of another Kentuckian associated with Harvard Forest: Nathaniel Southgate Shaler (1841-1906), originally from Newport, Ky., a student of the controversial Louis Agassiz while at Harvard. Shaler later became, as Foster wrote, “the dean of the Lawrence School of Science at Harvard, one of the great minds to teach natural history and geology at the university, [and] the founding power behind the Harvard Forestry School and the Harvard Forest.” (For a more unsettling overview of Shaler’s changing philosophies, I cautiously refer you to the Wikipedia article.) But, perhaps most interestingly, I also learned, after a copy of Foster’s 1999 book Thoreau’s Country arrived on my doorstep, that Foster, like my dad, built a cabin in the woods—his in northern Vermont—when he was a young man, and lived a solitary life there for several months. Foster had grown up in semi-rural Connecticut, in an area dotted by farms, which sounds very much like the area around Lawrenceburg where Pud roamed as a youngster. It seems to be a natural path, then, that both my dad and David Foster found their way to Harvard Forest to study and build a career. I have since shared with Foster the complete journal my father kept while working at Harvard Forest. The current director of the Forest found my father’s descriptions of the politics and infighting among the ambitious scientists fascinating, enlightening, and, unfortunately, commonplace. In return for sharing that gem with him, he has promised to look for my dad’s paper on bourbon, which is currently reserved in the Harvard Botany Library—two floors below Foster’s Cambridge office. Publishing The Last Resort continues to open new and surprising doors. I never imagined I would discover so many people who remember my father fondly and are willing to share their stories. It is even more astonishing to learn that the legacy he left behind as a scientist continues to inspire others in his field. What a journey this has been, finally piecing together a fragmented understanding of who my father was and what it means to be his daughter.  John Allen Moore John Allen Moore John Allen Moore would have turned 94 on March 20. This was the first year his family had to celebrate his birthday without him. John Allen was my father’s first cousin and one of the boys who hung out with Pud at Camp Last Resort. The two were fast friends. John Allen’s remarkable memory of my father and of our shared family lore was a primary impetus for the publication of The Last Resort. I dedicated the book to him. This week, my cousins Bob and Sandy Goodlett and I made what has become an annual trek to Atlanta to see our Moore cousins. By happy serendipity, our visit coincided with John Allen’s birthday. We were able to celebrate with his widow, Jane Chappell, and two of his four children, Deborah Costenbader, from Austin, and Cindy Caravas, from Virginia Beach. We also spent time with John Allen’s brother, Joe, and his wife, Jean. Upon our return to Kentucky, we learned that another of the Last Resort boys, “Rinky” Routt, had died in February, soon after celebrating his 98th birthday. We were saddened to get that news and to recognize that not one of my father’s Salt River companions is left to tell their stories. Our lives are cyclical, of course. We all walk the same inevitable path. But as I mourn those we have lost, I’m finding great joy in reaching out to others whose lives intersected theirs either tangentially or prominently. Getting to know John Allen’s children may promise as much joy as getting to know him late in his life. Reconnecting with my father’s friends, students, and colleagues—as well as my older cousins who knew him well—has augmented my understanding of him and of myself. My life is better because of these emerging relationships. If you have questions about your own family history, I hope you will find the courage to ask questions of those who may have answers. You may be surprised at what you learn. Perhaps more consequentially, you may develop friendships that will continue to exhilarate you. Time is short. Don't wait. In MemoriamSeveral individuals associated with The Last Resort have died since its publication in August 2017. I’d like to honor them here. To those who are mentioned in the pages of The Last Resort:

And to those who patiently endured my questions about my father or his Lawrenceburg ties:

|

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed