Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, Ga., describes her awakening to the racial inequities that remain endemic in U.S. society. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. I was blind, but now I see. As Black History Month 2021 comes to a close, I’m also marking nearly a year of much more time, and need, for mulling over the human condition. So, I’ve been reflecting on the evolution of my awareness of racism. I grew up a cis white female in central Kentucky. I went to a very small elementary school with zero Black students and a high school of 800 kids with around 15-20 Black students. I had much more experience with the Huxtable family, Sanford and Son, and the Jeffersons than I did with real Black people. It would be generous to describe my view of the Black experience and racial inequity as narrow. When 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was shot and killed, the scales fell from my eyes. At the time, my second son, a white boy, and his close friend and neighbor, a Black boy, were 12. It struck me suddenly that my son’s friend, my kind neighbors’ child, could have easily been killed in cold blood for walking around at night in a hoodie, just like Trayvon. This fact made me sick to my stomach, and it readjusted my understanding of racism. I hadn’t fully realized until then how a person’s Blackness still made him or her a target, and how a person’s whiteness gave him or her protection. That day I started to understand the concept of white privilege. I realized I had never felt the need to have a talk with my sons about how to act around police in order to save their lives during a traffic stop, or anywhere else. I never had to tell them to keep their hands out of their pockets when in a store, and to make sure they got a receipt, and a bag, at the checkout. I never feared that when they went out at night with friends, they might be shot and never come home. I felt guilty and embarrassed by my depth of ignorance around racial issues. In the last few years, I’ve learned more about the history of policing, cash bail, and mass incarceration. I’ve read the statistics on Black women’s health and rates of Black maternal death. I’ve watched the reports of how the coronavirus has stolen a disproportionate number of Black lives. I’ve heard the stories of racially motivated voter suppression laws, the higher rates of toxic pollution present near neighborhoods populated mostly by people of color, the racial bias in education and testing, and systemic racism that permeates nearly every institution throughout the United States and weaves its threads throughout our culture. I used to claim, “I’m not racist.” Now I know this: it’s impossible to escape the effects of racist ideas in a society that was built on racism and has laws that support racist policies still today. I believe it’s time we all consider getting on board with the Avenue Q song and just admit it—“Everyone’s a Little Bit Racist,” because we have grown up in a deeply racist society. Ibram X. Kendi explains that the only way out of this quagmire is to become antiracist. It’s not enough to try to be “not racist.” If people want to bring about changes that promote equity, we have to actively work to become antiracist individuals. From that place, we can work to bring about antiracist policies. His book How To Be An Antiracist has helped me see even more of my blind spots and learn how to overcome them, along with ways our communities, organizations, and laws can become antiracist. He shares stories of his lived experience along with the history of race as a social construct created to achieve a sense of supremacy and privilege for some people, and to strip it from others. Regardless of our physical characteristics and beliefs, I am certain that until all of us feel safe, cared for, respected, and valued, none of us truly are. Working at becoming antiracist is one step I can take toward promoting a more secure existence. I still have much to learn.

4 Comments

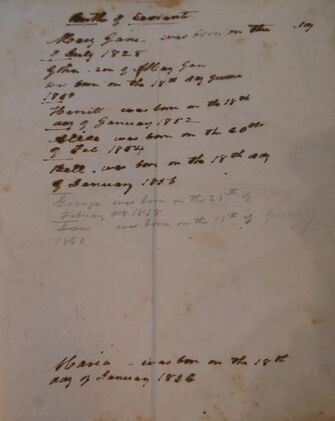

Image of a peaceful protest: the Women's March in Washington, D.C., the day after the 45th President's inauguration. I was there. Photo by Mary Henson. Image of a peaceful protest: the Women's March in Washington, D.C., the day after the 45th President's inauguration. I was there. Photo by Mary Henson. And so he has been acquitted, as we all anticipated. His loyalists never abandoned him, not really, even if some publicly wavered moments after he put their lives at risk. Because of that undying fealty, and despite what some pundits are saying, I fully believe he will run again. Why wouldn’t he? He craves the white-hot heat of that spotlight in the political crucible. He will crush all comers. As I watched the brilliant impeachment managers present their evidence last week, I alternated between traumatized, tearful, and comforted. Comforted because I realized how much I needed someone to confirm that this has all been real. I needed to see the horrors of his presidency presented in a cogent and organized way. Seeing the chaos neatly packaged helped me breathe again. It wasn’t just a terrifying, perpetual nightmare. Others saw it, too. Around the world, they were watching. I wish I could believe it is over. But his chilling words on Saturday tell us otherwise: “Our historic, patriotic and beautiful movement to Make America Great Again has only just begun.” We are all exhausted, and I intend to heed our duly elected President’s calls to move on. But we must remain vigilant. We cannot allow our hope and our relief to blind us to the anger and the violence of Trump’s toxic brew. We watched it boil over on January 6. He will turn up the heat again.  The first edition of Albert Camus’ “La Peste,” or “The Plague,” published in 1947. The novel is a fictional telling of a 20th-century epidemic. Its “truths” seem all too real to contemporary readers. The first edition of Albert Camus’ “La Peste,” or “The Plague,” published in 1947. The novel is a fictional telling of a 20th-century epidemic. Its “truths” seem all too real to contemporary readers. Back in December, in the awful year of our Lord 2020, I happened to flip on a news program just as author Salman Rushdie pronounced, “Lies are a way of obscuring the truth. Fiction is a way of revealing the truth.” Having taken numerous classes and read many books on fiction writing in recent years, this concept was not novel to me. (Sorry…) Nor is it original to Rushdie, of course. Writers Albert Camus and Jessamyn West, for example, famously used nearly the same words to relay the same idea. But I hurriedly scribbled the words on a pad of paper that I’ve learned to keep in front of the TV—my oracle for inerrant wisdom—and they’ve rolled around in my consciousness ever since. This week our nation will be subjected to yet another impeachment trial of Former President Donald J. Trump (or “the 45th President Donald J. Trump,” as he evidently prefers to be addressed). He is in this predicament once again because of his lies. He lied about the fairness of the election before the election, and he lied about the results of the election afterwards. He also pressed other people, such as Georgia election officials, to lie for him. Many, many people believed his lies, and, ultimately, his lies led to the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6. People died, and other people’s lives were threatened. Trump obviously felt it was to his advantage to “obscure the truth.” If he is not convicted, if he never faces any further accountability for his lies or the damage they caused, what deterrents will there be for other elected officials not to lie to further their agenda? Or to cry “Fraud!” every time they lose an election? In fact, our country seems to be so awash in lies that I’m not sure how we ever find our way back to the truth. Perhaps that’s why Rushdie’s comments have stayed with me. Some of the most powerful—or memorable—fiction tells the stories of ordinary people who find themselves in horrific situations: war, poverty, imprisonment, abuse, persecution, pandemics, social or political upheaval. It’s by temporarily inhabiting these fictional characters, seeing their world through their eyes and ears and emotions, that we can begin to understand their truth. It’s not until we actually feel ourselves in that battle or in that degrading circumstance, or we feel that hunger or those taunts or that pain, that we begin to fully grasp their reality. It may seem odd at first to think that a made-up story taking place in a made-up world is where we may logically find the most truth. But perhaps that imaginary incarnation permits greater honesty. Or perhaps it helps remove our own prejudices so we can see things more clearly. Which leads me to ask: Will we have to wait until some great works of imagination are written about these dark days—these days spent watching our democracy teeter on the brink—before we are able to fully untangle all the lies? Or can a nation of disparate peoples with disparate experiences and viewpoints finally, through sheer will, recognize a common truth so we can heal this country? This week the impeachment managers will carefully present all of the facts they have collected, drawing the clearest picture they can to support their contention that the former president incited the insurrection. But can they “reveal the truth” in a way that the majority of our citizens, let alone two-thirds of the Senate, will accept it? We’ve already seen most of the evidence. Many of us watched it play out in real time. But, still, we don’t agree on the appropriate response. The truth remains elusive. Fiction may be our last hope.  Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. It’s Black History Month, so it’s time for more reckoning. I have written freely in this blog about my family’s role in the lynching of a Black man, George Carter, in Paris, Ky., in 1901. I have written about my horror in learning about that incident. I wrote last summer about my rising fury at the unending injustice in this country that has led to the unconscionable loss of Black lives, tragedies that have been ongoing for generations but which have become more public with the advent of cell phone videos. I remain angry and disgusted with the lack of progress on the underlying issues that allow this to continue. I hope to write more about that before February comes to an end, and we give ourselves permission to stop thinking about these things until next February. Right now, however, I need to talk about the family Bible. I remember this Bible being displayed on a dropleaf cherry table in front of the picture window in our living room in Lawrenceburg, Ky., when I was a child. It was an enormous, handsome, heavy book, in good condition for a book of its age. I remember flipping through it; I remember noticing handwriting on some of the pages. But I don’t believe I could have told you what branch of my family it represented or anything about the people whose births and deaths and marriages had been noted. Recently a family member shared some photos she had taken of those pages. I immediately recognized that the Bible was yet another relic of my missing grandfather’s family, the grandfather who abandoned my mother shortly after her birth. The Bible was published in 1848, so the Bible first belonged to my grandfather Lyons Board’s grandparents, Dr. L. D. Barnes and his wife, Mary Parker Roseberry Barnes, of Paris, Ky. After all the research I—and others—have done into that family over the past ten years or so, I now recognize the names. Those of you who have read Next Train Out might, too. There’s the marriage of Dr. Barnes’ daughter, Mary Lake Barnes, to William Ellery Board, originally of Harrodsburg, in 1888. There’s the marriage of their only surviving son, William Lyons Board, to Nell Hardeman Marrs of Lawrenceburg, in 1920. There are the births—and the deaths—of all the children who didn’t live to adulthood, or didn’t even survive infancy.  And there are the births of the “servants.” The servants are identified only by first names: Mary Jane, John, Harriett, Alice, Bell, George, Dan, and Maria. The listing is separate from the “Family Record” listed in a fine hand on decorative pages. The handwriting on the servants page is less careful and difficult to read. It grieves me that I may not have all of the names correct. Another thing we have learned this year is how important it is to say their names. All of the servants were born between 1828 and 1860. All were born, I have to assume, into slavery. I don’t know that for certain, of course, And it’s possible they had been freed by the time they were listed in the family Bible. But any other scenario is hard to imagine in central Kentucky before the Civil War in a family of some status living in a county with a large population of slaves working expansive agricultural land. The fact that they are included in the Bible makes me want to believe that they were indeed considered members of the household and were treated gently and respectfully and were well loved by the Barnes family. None of that excuses the fact that some or all of them were at some point the property of the Barneses. I had already discovered some time ago that at least three of the four branches of my family once owned a small number of slaves, probably all doing domestic household work. I had already reckoned with that in some small way. It was not a surprise to discover this listing of the Barnes family servants. But it remains painful to see the evidence handwritten in such a personal way in the family Bible. Many of us from the South share a similar family history. It’s remote to us now. We’re talking about more than 150 years ago, after all. Nonetheless, I feel it’s important not to deny our intimate connections—no matter how tenuous, no matter how seemingly innocent—to the national shame our country has to bear, and bear witness to. My family played a role. The Bible tells me so. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed