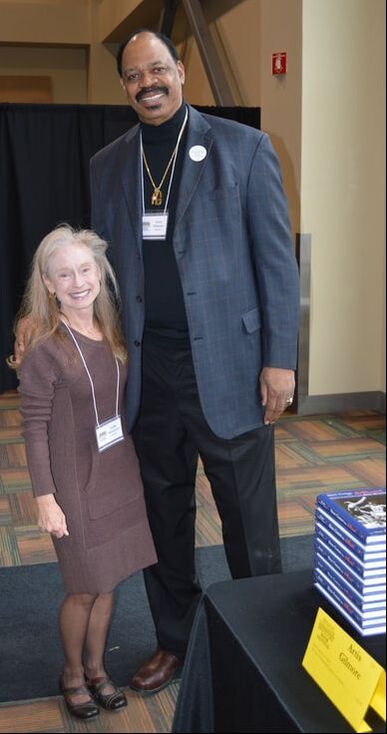

A photo op with the gracious Artis Gilmore at the 2018 Kentucky Book Fair. A photo op with the gracious Artis Gilmore at the 2018 Kentucky Book Fair. My name is Sallie, and I am a basketball fanatic. I blame my mother. About the time I was entering my early teens, I recall how surprised I was to find my serious, book-reading mother occasionally watching University of Kentucky basketball games on TV. I don’t remember her talking about basketball much, but she had taken me to a few high school games, where my cousins starred. Up until that point, though, I hadn’t thought of her as someone who watched sports on television. At the time, I was devoted to Wide World of Sports and broadcasts of the Olympic games, but no one in my household was a fan of professional sports. I couldn’t imagine how my mother had the patience for such a tedious, and to me at the time boring, pursuit. But I took notice. Basketball was not frivolous. Her interest had given it a certain heft. When I was in college, UK won a national championship. Shortly afterward, so did the University of Louisville. My interest was piqued again. When home for the holidays, I watched what games were available. I started developing loyalties and interest in the players. By the time I went to graduate school in Chapel Hill, N.C., I was hooked. While there, UNC and N.C. State won championships. I adored Jim Valvano. Some guy with an unpronounceable name had just started coaching at nearby Duke, trying to pull that team up from the bottom of the heap. Michael Jordan, Sam Perkins, Matt Doherty, and Brad Daugherty wandered in and out of the foreign languages building where I taught. I was mesmerized. Settling back in Kentucky after school, there was almost no way to avoid full basketball fanaticism. It was all around me. It was what I had in common with the majority of people I encountered. Some were suspicious of me because I rooted for both UK and UofL. But I was a pure college basketball fan. If a team was on TV and the players had signs of talent, I was interested. I was awed by their athleticism. By their tenacity. By their skill. If you know me at all, you’ve probably heard me say, “God gave Kentuckians basketball to help us through our dark, dreary winters.” Why else would the typical college basketball season begin when the time changes in November and end in April, just as we’re all busting to get back outside? Some of my friends still have trouble reconciling that someone who loves a good book and a classical music concert also loves college basketball. Thankfully, I have a handful of cousins who are just as diverse in their interests as I am. During this strange basketball season and the unexpectedly exciting men’s NCAA tournament, my cousins and I have connected from our homes in two different (rival) states. It’s been sheer delight watching their take on the games: the scientist who’s crunching the stats in real-time; the former player who’s questioning the coach’s call or the offensive set; the UofL and IU grad who’s trying to remain loyal to his alma maters and the Big Ten while honoring his Kentucky roots; and me, the simple-minded humanist who’s interested in the characters and the drama that’s playing out on the floor. While my cousins are breaking down plays, I’m texting “Woohoo! What a pass.” I don’t see the intricacies of the game; but I do see effort, determination, teamwork, and joy. Another basketball season is about to end. I have a favorite team in the Final Four whose players unexpectedly earned my love and devotion only a month ago. The two teams I followed all season never even made it into the tournament. Initially I thought that meant I’d have a March free to do other things, but I surprised even myself. I adapted. I watched the games because I find beauty in the athletes’ ability. It makes me happy. And these days, that’s the only reason I need to invest some time in front of the TV. P.S. Before you ask, of course I’m an equally avid fan of the women’s game! I’ll pull for our SEC arch-rival South Carolina in the Final Four, even though it hurts just a bit.

4 Comments

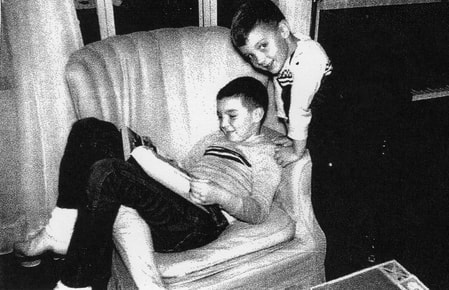

Vince Fallis, mugging for the camera, while his older brother, Dave, lounges in the chair. Vince Fallis, mugging for the camera, while his older brother, Dave, lounges in the chair. Vince Fallis, of Rabbit Hash, Ky., recalls a previous nationwide vaccination effort. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. On March 9, I received my second dose of the Pfizer vaccine at a well-organized assembly line managed by St. Elizabeth Medical Center, also known as The Empire around these parts. I was in the old folks group because I am one. Everyone seemed eager, yet somewhat reserved, as we went through the process. I profusely thanked the vaccinator, since I understand most are volunteers. I think we should have a parade for them when this is over (if it is ever over). I felt somewhat elated as I drove away. Barbara and I will now be able to see the granddaughters. That has not happened since last fall. Excruciating. The whole experience also brought back the memory of a day in 1955 when I stood with my parents, Leonard and Virginia, and my brother, Dave, in a long line outside Beechwood School to receive the Salk vaccine. I knew very little about polio but remember seeing on our black-and-white TV the images of dreary, hopeless hospital wards filled with iron lungs with only the heads of the pitiful victims visible. In our minds the polio vaccine was a miracle that would keep us from the fate of those we saw in those terrifying hospital scenes. However, as an 8-year-old standing in that line, I was experiencing what I would now recognize as an approach-avoidance conflict. Some years before I had undergone the painful series of rabies shots after a dog bite, and I wasn’t sure how closely this vaccination would match up to that somewhat traumatic memory. But I survived, and we were thrilled to do our part to eliminate the dreaded virus. Drs. Salk and later Sabin became national heroes. Fast forward to the present day. With over 550,000 of our fellow Americans already struck down by the novel coronavirus, many of my surviving fellow citizens have now made shunning the vaccine an emblem of personal freedom, tribal politics, or general disbelief in science. Substantial numbers of adults—many with higher education and, I must assume, a reasonable level of intelligence—have chosen to decline the vaccine. Barbara recently said that if polio threatened us today, it would not be eradicated. I agree. Perhaps more disturbing is our total inability to come together for the common good. We see other acts of humanity: volunteers handing out boxes of food to long lines of people who have lost their livelihood during the pandemic; donors generously opening their wallets to help those in areas stricken by natural disasters; yellow-vested volunteers walking through Chinatown to deter criminals who are attacking people of Asian descent. Many choose to participate in these acts of compassion, but protecting each other from a deadly virus is, for some, a bridge too far. I’m coming close to going off the rails, but I must say one more thing. We should all be outraged when we see white males wearing clothing displaying Nazi images. My uncle, John C. Goodlett, the father of my dear cousin, Sallie Showalter, walked through one of the death camps during World War II. We have a handwritten letter in which he describes the experience. I often wonder how he did not see those images every night when he was trying to sleep. This country yearns for a new call to the real meaning of Patriotism, not one based in hate and exclusion, but one that lifts us up by working for the common good of everyone in this country. Will this happen? You may be skeptical. But I remain the eternal optimist. Peace be with you.  Does this young fella look like a criminal? As an adult, he stole over $20,000. Does this young fella look like a criminal? As an adult, he stole over $20,000. I am a descendant of thieves. One grandfather—while a partner in an automobile dealership—stole a friend’s 1920 Oakland Sedan and then wrecked it, resulting in damages to the tune of $1,000. During the Great Depression, my other grandfather evidently mismanaged some county funds, perhaps to his benefit. About the same time, my maternal grandmother’s half-brother, while working in the Kentucky Auditor’s office, pocketed more than $20,000 in state money in an elaborate six-year scheme. In 1885, my great-great uncle was charged with embezzlement in Kentucky—a great embarrassment, evidently, to his many benefactors, including U.S. Senator Joseph Clay Stiles Blackburn. In 1897, the same uncle was charged with forgery in California. Embezzlers. Grifters. Hucksters. Glory be. Before their alleged malfeasance was exposed, each man had by all accounts been a well-respected government functionary or businessman, a churchgoer from a locally recognized family. There had been not a whiff of impropriety, as far as I’m aware. But something compelled each of them to make a bad decision, or a series of them—to take risks that may have been uncharacteristic of their normal dealings. The temptation was too great. Human frailty prevailed. When the repercussions became apparent, two ran away, leaving Kentucky behind. Two didn’t live to see the matter resolved. Family paid the price of their perfidy. We are more than our misdeeds, of course. We are all complex: good and bad, wise and foolish, brave and cowardly, generous and selfish. None of us can predict how we might have responded to their particular circumstances. As I chew on another juicy tidbit about my mysterious ancestors, I have to remind myself not to let that one savory crumb define them. I have learned that families don’t tend to share this information with each other. Why not just sweep it under that very lumpy rug? Nothing good could come from talking about the family troubles. After all, these problems were all in the past, safely locked away in faltering memory. That is, until some nosy granddaughter starts picking through yellowed newspaper articles. On the one hand, I am happy that my ancestors were “colorful.” I would have lost interest long ago if they had only been Sunday School superintendents and hard-working family providers. In small towns like Lawrenceburg and Paris and Harrodsburg, some of that probity would have gotten them mentions in the local newspapers. As it was, the society pages detailed their comings and goings. But, as always, I imagine the scandals sold more papers. What this teaches us, of course, is that our ancestors were just as complicated as we are. Each of us has had moments when we filled with pride and moments we hope will never be known to any other living soul. Unfortunately for my ancestors, these particular moments of weakness, these missteps were captured by the press—or the courts. If we’re lucky, no yet-to-be-born great-granddaughter will stumble across accounts of our failings. Perhaps the public persona we’ve all so carefully crafted for our friends and families—and ourselves—will hold. But our moral failings partially define us, whether we want to admit it or not. We’re not just the sum of the good things. It’s never that simple. Some of my ancestors were thieves. And loving husbands and fathers. And hard-working citizens. And human beings, as inscrutable as we all are. Sometimes even to ourselves. I would be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge my good friend Tessa Bishop Hoggard, who provided many of the newspaper clippings related to these incidents. Lord knows why she has found my family so interesting, but I am indebted to her research prowess and the gift of her time. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed