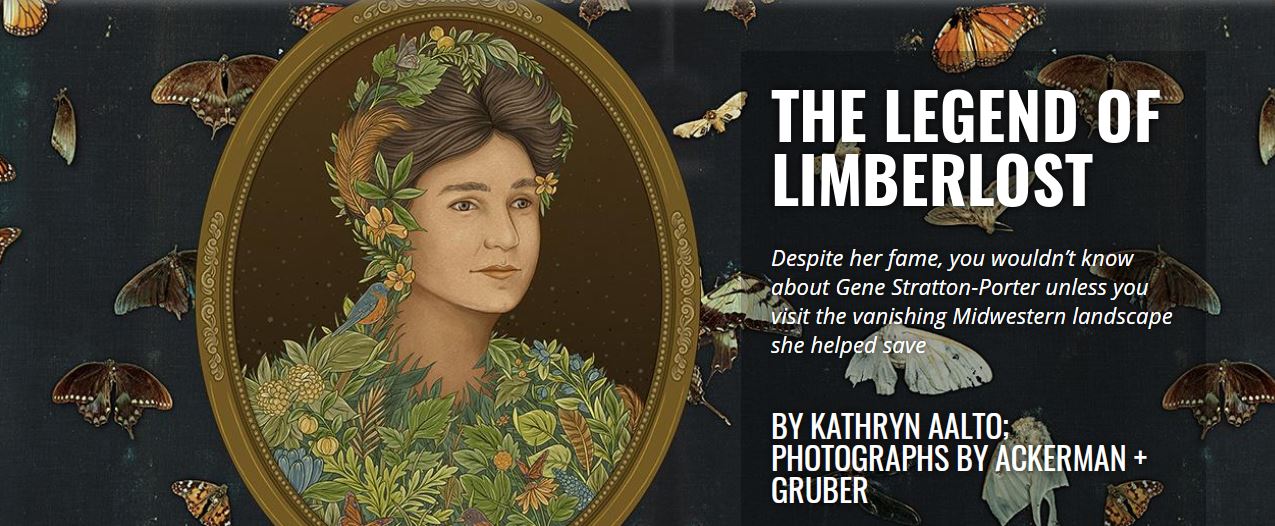

A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? Recently I wrote that I now have two books in my “catalog.” As I worked on the second book, it frequently occurred to me what strange bedfellows they are: a first-person narrative by a still innocent 19-year-old naturalist driven to document the flora and fauna inhabiting his halcyon getaway; and an almost gritty tale of a man stripped of his innocence who leaves his home behind and wanders from one commercial/industrial area to another with hardly a nod to the natural world around him. I love to spend time outdoors, and I sometimes feel ill-at-ease in the city. I am the daughter of a naturalist, a scientist who could identify any specimen he encountered during an amble through the woods. I, however, was never disciplined enough to fully develop his prodigious skills. While I can identify many native woodland trees and common birds, the names of most wildflowers, grasses, and garden plants are a mystery to me. And I truly regret that I can’t recognize bird songs. For years I was certain that that shortcoming alone disqualified me from writing a novel. Successful fiction is full of lush details of blooming flowers and the bees hovering around them. Or a prairie of grass and the animals that live there. Or a midnight sky and the constellations that awe us. In “Seeing the World Around Us,” I mused about the importance of being able to name a thing for that thing to fully enter our consciousness. Without that ability, we are blind. We look past the diversity of life all around us. We come to consider ourselves the all-important foreground spotlighted against an indistinguishable background. I still believe that my deficiency seriously weakens my ability to provide the sensory details readers need to feel a place. The plants and critters who share our space define our world, perhaps even define a part of who we are, even if we can’t always recognize them. So when I had a story I just had to share with others, and a fictional narrative seemed the only way to tell it, perhaps I was fortunate that that tale largely unfolded in cities or confining indoor spaces—steamy kitchens, tiny apartments, the birthing bedroom. I stole a few opportunities to place my characters outside in the fresh air. In retrospect, it’s clear that my characters, like their creator, look outdoors when they are seeking balm for a troubled soul, or a place for reflection. I was reminded of my inability to fulsomely describe a lush plein air scene as I read a recent article in Smithsonian magazine, sent to me by my cousin Barbara, about an acclaimed “naturalist, novelist, photographer and movie producer” whose name I had never encountered: Gene Stratton-Porter, born Geneva Grace Stratton in Wabash County, Indiana, in 1863. Perhaps I’m showing my woeful education by admitting I was not familiar with her, since both Rachel Carson and Annie Dillard cite her as a keen influence. I have not read any of her work—fiction, nonfiction, or poetry—but I can only imagine the richness of the natural scenes she portrayed. Her intimate knowledge of the Limberlost wilderness she wrote about, gained during countless days exploring on horseback and waiting quietly for the perfect photo, must make her tales of plucky young girls and strong women come alive. Stratton-Porter evidently brought to her writing both my father’s ability to document the natural world and my desire to tell a personal story. She had both the scientist’s eye and the writer’s imagination. In addition, she had the patience of a photographer, willing to devote the time needed to capture the most arresting photo, and then to indulge in the careful writing necessary to relay that vivid image, and her human response to it, in words. Amid all her talents, Stratton-Porter most relished her simple sensory responses to the world she discovered while wandering outdoors: “Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras.” I, too, am a nature-lover, not an academic or a trained naturalist. As life seems to slow for all of us, perhaps this is the time I need to devote to not only admiring but learning to name the beautiful things that catch my eye and restore my soul. The author of the Smithsonian article, Kathryn Aalto—a landscape historian and garden designer, as well as an author of several books—is herself a master at describing natural detail. Her first paragraph immerses the reader in northeastern Indiana’s Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, a small part of the vast swamplands that Stratton-Porter spent her life documenting: “Yellow sprays of prairie dock bob overhead in the September morning light. More than ten feet tall, with a central taproot reaching even deeper underground, this plant, with its elephant-ear leaves the texture of sandpaper, makes me feel tipsy and small, like Alice in Wonderland.” Stratton-Porter also recognized early the danger of mankind’s desire to tame the land for our own use. As Aalto writes:

“Twenty years before the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Stratton-Porter forewarned that rainfall would be affected by the destruction of forests and swamps. Conservationists such as John Muir had linked deforestation to erosion, but she linked it to climate change: “It was Thoreau who in writing of the destruction of the forests exclaimed, ‘Thank heaven they cannot cut down the clouds.’ Aye, but they can!...If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distill moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, they prevent vapor from rising. And if it does not rise, it cannot fall. Man can change and is changing the forces of nature. Man can cut down the clouds.”

0 Comments

Nobel Prize-winning writer Czeslaw Milosz is often quoted as saying, “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.”

I stumbled across this quote recently when reading about the one-woman play based on Elizabeth Strout’s novel My Name is Lucy Barton that opened earlier this year in New York. I chuckled. As I have pursued publishing two books about family members—one about my father who died when I was seven, and the other about my maternal grandfather whom my mother never knew—I have frequently wondered about the propriety or even the dangers of writing about family. In my case, I did not set out to write a “tell all” book or to reveal any uncomfortable truths about my personal experiences. In The Last Resort, I essentially let my father do the talking, and I was cautious not to include in the excerpts from his Harvard Forest journal any details that I thought might be construed as too personal or too negative toward those in his orbit. Nonetheless, I did want to reveal just enough to make him feel more fully human to readers. Next Train Out is, of course, a novel. It is a fictionalized telling of my grandfather’s life. I relied on the facts I had at hand to discern possible motivations or character traits that would lead him to take the actions he did. Some may consider the details of the story scandalous or horrifying. I simply view them as the facts. Nearly all the people who populate these books are long gone from this earth. That distance gave me some comfort and perhaps the license to share these stories. At the same time, I felt some responsibility for making my representation of the characters as truthful as I could, given the limitations of my knowledge. I would sometimes ask myself, “If Effie Mae’s descendants were to read this book and somehow recognize her in the telling, will they feel I have maligned her memory?” I don’t think so. There is one character in Next Train Out who is portrayed as a sort of villain, which I don’t believe is truly accurate. But I needed a foil for Lyons, and he was a good choice. I checked with his great-grandsons—my cousins—twice to be sure they would be OK with my fictional representation. They assured me I didn’t need to worry. Another cousin called recently to say how delighted she was to find her grandfather and other relatives identified by name in the novel. It made the whole story come alive for her. She probably didn’t remember that I had called her late last year to be sure she was OK with my using their real names. During that conversation, she offhandedly shared some physical and personality traits of those family members with me, which I dutifully incorporated into the story. So it can indeed be dangerous to have a writer in the family. Or in your circle of friends. But, as Anne Lamott wrote in Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”  John Prine, from the Bruised Orange album cover. John Prine, from the Bruised Orange album cover. Charles Goodlett, of Zionsville, Ind., captures the sense of helplessness and grief so many of us are feeling as Covid-19 strikes our friends and our heroes. If you would like to submit a posting for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. We heard last night that John Prine succumbed to COVID-19 in Nashville, having been critically ill for at least a week. It shocked and saddened me and elicited a melancholic reflection back 50 years, reminding me how much his music, especially his first album in 1970, infused my entry into young adulthood. When I was a senior in high school and just coming of age in the tumultuous era of Vietnam War protests, culture wars, Nixon, drugs, and the shock of assassinations, riots, Kent State, and paranoia, this album shed resonating light on the hardships of everyday people with humor, irony, and grit. “Sam Stone” is a gut punch about the consequences of Vietnam combat, heroin addiction, and PTSD. The carefree pleasure of getting high and “just trying to have me some fun” was the theme of “Illegal Smile.” “Spanish Pipedream” described a deserting soldier's escapist dream. “Hello in There” offered an unforgettable immersion into the loneliness of growing old. And, of course, who can forget the mocking sarcasm directed at hypocritical Christian patriotism in the chorus of the song whose title is its first line: But your flag decal won’t get you into Heaven anymore They’re already overcrowded from your dirty little war Now Jesus don’t like killin’, no matter what the reason’s for And your flag decal won’t get you into Heaven anymore "Six O’clock News" reminds us of the life story behind the shocking destruction of a young man. And then there's the anthem for all rebellious Kentuckians (and a rage against Mr. Peabody’s corporate environmental destruction well before anyone ever mentioned global warming), a favorite of so many, “Paradise”: The coal company came with the world’s largest shovel And they tortured the timber and stripped all the land Well, they dug for their coal till the land was forsaken Then they wrote it all down as the progress of man Chorus So Daddy, won’t ya take me back to Muhlenberg County, Down by the Green River, where Paradise lay. I’m sorry my son, but your too late in asking, Mr. Peabody’s coal train done hauled it away. Listen to my 6-minute tribute, featuring one of Prine's most frequently performed songs, “Angel from Montgomery.” Prine was a singer-songwriter with a legendary cult following who served up folk tales of biting humor—all told in stories about people, the truth unvarnished with searing insights and hilarious wit. He captured life’s humor and made it more interesting and fun for all of us. Perhaps the most hilariously ironic statement of independence in all of folk/rock is the first verse of “Sweet Revenge” from his album of the same name: I got kicked off of Noah's Ark I turn my cheek to unkind remarks There was two of everything But one of me And when the rains came tumbling down I held my breath and I stood my ground And I watched that ship go sailing Out to sea John, we are all mourning your death while poignantly celebrating your life by singing along with you one more time, with a tearful twinkle in our eyes. Benediction[offered by Sallie Showalter] In late March, soon after the news broke of John Prine's diagnosis, my friend Peter Berres of Lexington, Ky., eloquent and sage writer about the Vietnam conflict, sent me a Prine performance of "Hello in There." In Berres' words: "Forty-five years of bringing, at least, a tear to my eye each and every time I listened (hundreds to thousands?). This seems like one of the most poignant performances, in my mind. I suppose it may have something to do with our times and situation. Been watching this daily for several weeks. Now, with news of his diagnosis, watching has transformed into treasuring this performance, this song, this man..." |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed