Photo by Rick Showalter. Photo by Rick Showalter. My husband and I spent Thanksgiving Day raking. An acre of property, 40 mature deciduous trees. We barely made a dent. Nonetheless, it was a rare sunny, cool day and a pleasant way to avoid any potential holiday stress. The irony of our labor didn’t strike me until a friend called me out. “So, you’ve been out raking the forest floor, huh?” he chided. “Doing your part to prevent local forest fires?” Most of us have enjoyed the sardonic memes posted by the Finns after President Trump’s public statements about how the good citizens of Paradise, Calif. (not “Pleasure,” dear President) could have avoided near annihilation if they had properly raked and cleaned the floors of the nearby forests, like the Finns. (Never mind that the Finnish President has denied ever mentioning “raking” when talking with President Trump. Or the fact that the Finns have complex structural and systemic ways of preventing forest fires in their country.) Twitter exploded with photos of Finns smiling with their rakes and references to #RakeAmericaGreatAgain and #Rakenews. In the Washington Post, columnist Philip Bump kept a straight face as he calculated how many man hours it would take to sweep and cart away all of the debris on America’s forest floors. And how much of our budget would be required for the purchase of equipment for that purpose. (No mention was made of the devastation that would rain upon forest critters large and small who depend on that debris for cover or sustenance.) All humor aside, the rampaging wildfires are real. The loss of life is real. Those who survived have found their lives totally upended, with no home, no supplies, no job to return to, no idea of what their future holds. The president is right that we must find a way to prevent this sort of devastation. We must work together to protect land and property and lives. But we cannot do that successfully until we admit that climate change is worsening the natural disasters afflicting us around the world. As the Camp Fire in northern California raged, Cal Fire spokesman Bryce Bennett told the Sacramento Bee, "Right now, Mother Nature is in charge." That will never change. But there are things we can do to mitigate the conditions that fuel droughts and wildfires in the western part of our country, floods in the east, and hurricanes along the coasts. Unfortunately, we as a nation have no appetite for addressing what is at the crux of the problem: greed and a craving for comfort. We seem unwilling to make sacrifices to protect our forests, our shorelines, our food sources, our water supply, the purity of our air, or the diversity of our ecosystems—despite the avalanche of data about what our future holds. For some reason, other countries see the writing on the wall and have joined together to protect their citizens’ interests, while here in the U.S. we strip environmental regulations, over-develop threatened areas, and decry a “War on Coal.” A persistent chorus of experts, thankfully, continue to sound the alarm. Another month, another comprehensive report about imminent catastrophes from climate change. Last month scientists representing the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned of the dire consequences we can expect by 2040 if we don’t take steps now to slow the warming of the planet. This month—the day after Thanksgiving, alas—13 federal agencies in President Trump’s executive branch predicted economic devastation by the end of the century if we don’t heed the warning signs. According to the New York Times, “All told…climate change could slash up to a tenth of gross domestic product by 2100, more than double the losses of the Great Recession a decade ago.” The projected price tag for our inertia? “$141 billion from heat-related deaths, $118 billion from sea level rise and $32 billion from infrastructure damage by the end of the century.” International trade will be disrupted. Agriculture will suffer. Diseases will spread. The numbers of people dying in heat waves and storms will dramatically increase. You would think that would get President Trump’s attention. He likes to think of the value of things in dollars and cents. Perhaps someone will finally convince him to listen to his administration’s experts at NASA, NOAA, the EPA, and other agencies. But don’t hold your breath. We’re not talking about the future any more. We’re talking about now. We’re talking about the devastation that is occurring in our own country right now. And we’re still sticking our heads in the sand. Here in central Kentucky, we’ve had 20 more inches of rain than we typically have by this time of year. We’re mired in mud and mildew. The grass is still growing. I have a lot of raking yet to do. Our lives may have been inconvenienced. But we still have our home. Our health. We’re comfortable, you know. But for how long? What will it take for us to act?

0 Comments

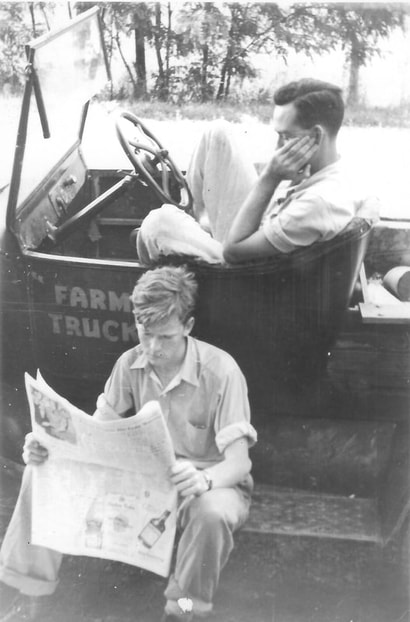

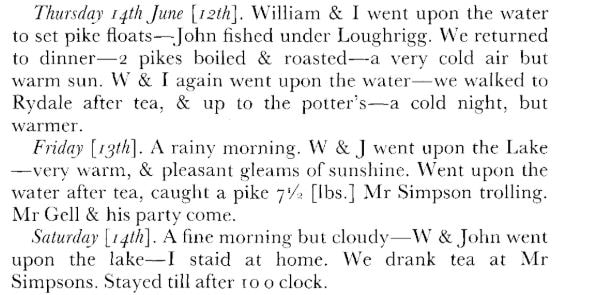

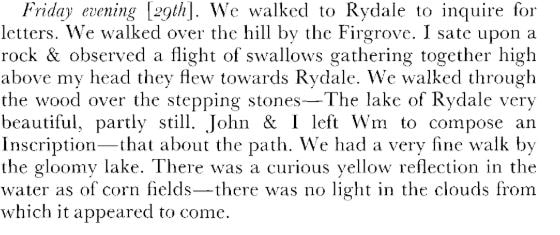

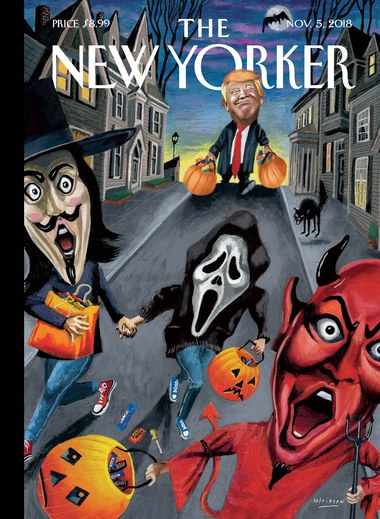

I was unable to hide my delight when poet Maurice Manning wanted to discuss "The Last Resort" with me after his reading at The Berry Center on November 10. Photo by Rick Showalter. I was unable to hide my delight when poet Maurice Manning wanted to discuss "The Last Resort" with me after his reading at The Berry Center on November 10. Photo by Rick Showalter. Here in Kentucky we have a sometimes shocking ability to rub elbows with the literary lions who live among us: Bobbie Ann Mason, Silas House, Maurice Manning, Richard Taylor, Crystal Wilkinson, Ada Límon, Mary Ann Taylor-Hall, Ed McClanahan, bell hooks, C. E. Morgan, Robert Gipe, Frank X Walker, Kim Edwards, Gurney Norman, and, of course, Wendell Berry. It was at a Kentucky Arts & Letters event sponsored by The Berry Center in New Castle, Ky.—in Wendell Berry’s beloved Henry County northeast of Louisville—that I was recently approached by award-winning poet Maurice Manning. I had interacted with Manning intermittently when I worked at Transylvania University, where he is a professor of English and the Writer in Residence. At last year’s Kentucky Book Fair, writer (and Lawrenceburg resident) Bobbie Ann Mason had alerted me that Manning had read The Last Resort and was enamored by it. But I didn’t really think he knew who I was or would recognize me in a large crowd of admirers. His first words stunned me: “Your dad’s journal is one of my favorite books of all time.” I’m fairly certain I stared at him stupidly, my mouth agape, as I tried to formulate a gracious response that didn’t fully betray my giddiness. We ended up talking for a while, and he relayed to me that my dad’s writing reminded him of the journals kept by William Wordsworth’s sister, Dorothy. Now I was an English major many decades ago, and I paid my respects to the English Romantic poets once upon a time, but I was not familiar with Dorothy Wordsworth. So I did what every 21st-century faux-researcher would do: I googled her and read a little of her work. And Manning was right. I was stunned at the similarity between her reporting of the day-to-day events of her life with her brother, William, and my dad’s reporting of the day-to-day activities at the Salt River camp with Bobby. Here is an excerpt from her Grasmere journal, which she began keeping in 1800: The rhythm of her days during that summer feel very much like the days spent at The Last Resort in the 1940s. Like Pud, Dorothy meticulously captures the details of the weather as well as the practical results of the fishing outing. The daily menu plays an important role in her notes. In another entry, she writes: “I went & sat with W & walked backwards & forwards in the Orchard till dinner time - he read me his poem. I broiled Beefsteaks.” Like Pud, and like most poets and artists of her era, she also paid close attention to her natural surroundings. William Wordsworth had said of his sister, “she gave me eyes, she gave me ears,” and the descriptions in her journals were sometimes the inspiration for his poems. The following extract from her Grasmere journal seems strikingly similar to entries in The Last Resort: I occasionally find poetry in the simple journal my father kept at the camp along Salt River. But I had not considered how similar his inclinations and his observations were to the aesthetics of the great Romantic poets. In a later email, Manning wrote to me, “your father's journal reminds me very much of the Romantic poets from the late 1790s, namely Wordsworth and Coleridge when they were both living near Nether Stowey, in Somersetshire.” Imagine that. Pud Goodlett, scientist, naturalist, ecologist, Romantic.  Crystal Wilkinson, left, prepares for a conversation with Wendell Berry, right, at The Berry Center's Kentucky Arts and Letters event Nov. 10, 2018, in New Castle, Ky. The two authors talked about their rural upbringings that evoked the strong sense of place in their writing and how the family members who loomed large in their early years play significant roles in their work. Photo by Rick Showalter. Just a reminder: More than 150 authors—including Bobbie Ann Mason, Silas House, Wendell Berry, Crystal Wilkinson, Mary Ann Taylor-Hall, and Richard Taylor--will be armed with a stack of books and ready to talk with you at the 37th Kentucky Book Fair Saturday, Nov. 17, 2018, at the Kentucky Horse Park near Lexington, Ky. If you love books and the people who write them, you don’t want to miss this event.  The first edition of Lewis Carroll’s "The Hunting of the Snark," March 1876. Illustration by Henry Holiday. The first edition of Lewis Carroll’s "The Hunting of the Snark," March 1876. Illustration by Henry Holiday. I never intended to stumble into a career as a writer and editor. I chose my college major based on which professors appeared to be the most entertaining or, perhaps I should say, the most inspiring. Although both my parents had been scientists, I loathed the idea of spending beautiful fall afternoons in dark, windowless labs. I decided, however, that I could spend those afternoons sitting under a tree reading a book. And so I did. I went to graduate school largely because someone—or rather some institution—offered to pay my way. And probably because I still had no idea whatsoever what to do with myself. So I spent two and a half more years studying literature and—much to my chagrin—philosophy and literary criticism. But, as I discovered only recently, it appears all I would have needed to do to become a clear, effective, and even amusing writer would have been to read the words my father left behind. I could have avoided all of that formal education if I had just pored over his publications. Reading academic papers about fragipans, tree throws, and surficial geology, however, wasn’t really my cup of tea. I knew that my dad’s colleagues had regularly praised the clarity of his writing, and he had demanded the same standard from his students. And I had seen glimpses of those practices, as well as his innate poetry and cleverness, in the two journals and the letters I had studied at some length to publish The Last Resort. But the other day I read three short book reviews my father had written in the early 1960s, which David Hoefer had unearthed in a search for all of my father’s publications. And I finally understood just what everyone had been talking about. In my favorite, my father references a Lewis Carroll poem to make a point about the author’s conclusions. David has now educated me about the seriousness of the book’s thesis in academic circles, but most of that flies blithely over my head. I have insufficient understanding of the content of the books my dad reviewed to embrace or reject the accuracy of his arguments. But I can evaluate his writing. In his review of the book The Upland Pine Forests of Nicaragua: A Study in Cultural Plant Geography by William M. Denevan, my dad remained unconvinced that Nicaraguan natives had used fire to manage the original forests despite Denevan’s repeated assertions, assertions that my dad felt lacked documented evidence. In wrapping up the review, he writes: "The aboriginal pyromaniac may indeed have produced the pine forests of Nicaragua, but Mr. Denevan does not convince me. I am reminded of Lewis Carroll's Bellman in The Hunting of the Snark: 'Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice: What I tell you three times is true.'" I was not familiar with this particular Lewis Carroll poem, although I now realize that his Jabberwocky is one of the few I have even partially memorized, thanks to Carroll’s books being omnipresent during my childhood. And his exposure of the inanity of repeating phrases of questionable veracity feels especially relevant today. Here are the first two stanzas of the poem: "Just the place for a Snark!" the Bellman cried, As he landed his crew with care; Supporting each man on the top of the tide By a finger entwined in his hair. "Just the place for a Snark! I have said it twice: That alone should encourage the crew. Just the place for a Snark! I have said it thrice: What I tell you three times is true." --The Poetry Foundation The book review my father penned appeared in Agricultural History, Vol. 36, No. 3 (Jul., 1962) and was indeed a serious academic critique of a work that remains relevant today. David Hoefer tells me that my dad’s skepticism, though perhaps a valid criticism at the time, has since been largely addressed as more evidence has been presented. But it was my dad’s introduction of a totally disparate text, a Lewis Carroll nonsense poem, to drive home a point that caught my attention—and made me chuckle. And that is the writer I want to be.  John Allen Moore reads the newspaper as Bobby Cole snoozes. John Allen Moore reads the newspaper as Bobby Cole snoozes. Tim Cooper, of Oakdale, Minn., does not consider newspaper journalists the enemy of the people. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Let’s think of this as an experiment. Twenty people are brought into a room and are monitored by 20 other people. Each participant has a comfortable chair, perhaps a cup of coffee. The monitor is nonintrusive but alert to his or her assigned participant. The participants are given a copy of the Sunday New York Times and told they have one hour to read the paper. As participants choose sections of the paper to read, the monitors will record their preferred order and the titles of the articles they read. Simple. Or maybe not. The premise of the experiment is, perhaps, a leap of faith. The idea of sitting down, reading the paper, developing a passion and a cadence for a paper’s nuance seems antiquated with the preponderance of devices that continually distract us. And, it seems to me as I get older, abundantly necessary. J. D. Salinger once wrote, “(T)he goal of education should be wisdom, and not just knowledge.” Salinger’s words, extrapolated to a broader understanding, demand us to be thinkers, not simply reactors. Our democracy is not one of passivity, but rather one that is participatory. And can there be a more profound way to immerse ourselves in the social, political, and cultural world of our participatory democracy than the simple act of reading a newspaper? I emphasize the order of the sections that we read for no great intent. I am simply amused that my newspaper reading habits are so rigid. Here’s my Sunday New York Times sequence: 1) Book Review; 2) Travel; 3) Sunday Review (opinion pages); 4) Arts & Leisure; 5) The New York Times Magazine; 6) front section. I book end my reading with something I dearly love—book reviews/discussions—and something I am driven to immerse myself in—the unfolding of the world’s events. In between, I vacillate between dreaming and thinking. During the week, I follow a similar practice with the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. And you? When I was 15, my father demanded that I read the morning paper (The Louisville Courier-Journal) from cover to cover before he awoke and came to breakfast. Perhaps my committed truancy sparked that directive. Suffice it to say, he was fearful that I would develop into an uneducated, ill-informed young man without a clue about the world. And I think he intrinsically knew that reading a daily newspaper and being forced to distill its disparate parts into something cogent was an education in and of itself. When he was situated at the table, my job was to give him an accurate and detailed précis of the paper’s contents. His order, too, was unchangeable: 1) sports; 2) front section and op-eds; 3) local news; 4) arts. I think that what this practice solidified for me was the notion that there is a seamless whole between the past, the present, and the future, and that newspapers are indeed the first draft of history. I am unabashedly political, obsessed with our electoral process, curious about public policy. I am appalled by the fear, loathing, and contempt currently practiced by our executive-in-chief. I am captivated by the young progressives running for public office who, to use Jon Meacham’s phrase, call us to our better angels, who are aspirational rather than dismissive. The photo in The Last Resort of John Allen Moore intently reading the newspaper while seated on the Model T running board makes my heart sing. What is he reading, what is he thinking? What discussions did his reading prompt with Pud, Bobby, and any other visitors to the camp? No matter, he is simply reading. A lesson for us all.  Photo provided by Joe Ford. Photo provided by Joe Ford. Joe Ford of Louisville, Ky., muses about Halloween and what is true. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Halloween was rainy in my neck of the woods. The few kids who braved the weather were either soaked—layers of costumes wet and matted together—or covered by plastic ponchos that hid their costumes entirely. I missed the costumes but took solace in the realization that the candy was, well, all mine. Of course, I buy the kind I like most—Snickers, Peppermint Patties, Dark Milky Ways—for just such a scenario. My wife, recognizing a temptation too hard to resist, won’t let the stuff stay in the house, so I take it all to work and eat it over the next couple of months, er, weeks. OK, days. I feel terrible though. Some neighborhoods in my city declared Halloween to be the day before the true day in anticipation of better weather, or even the weekend before, to avoid a school night. This is disturbing, as bogus as a Donald Trump speech (i.e., “not genuine or true”). I do believe that teachers should avoid big homework assignments or papers due on November 1. But managing your homework and activities and chores—milking the cows, bringing in the harvest—are part of Halloween. Well, maybe not the milking part. I think that happens in the morning. And maybe not the harvest part, as that sounds like a lot of work. But you get my drift. Halloween is for Halloween. It is the day before All Hallows Day, that is, All Hallows Eve. What are all those saints supposed to do? They’re no doubt totally confused. I did carve a pumpkin this year, in an effort to keep some traditions that make life enjoyable even though my daughter has moved away to college. Someone suggested I cut out the bottom of the pumpkin rather than the top. Let me say that again: cut off the bottom of the pumpkin. Duh! You would think that at my age I would have at least heard about that. I’ll say this: it works brilliantly! You can cut a larger hole to remove all the brains, and you don’t have to scrape the bottom part at all. I did sit out on the porch with my cauldron of candy and jack-o-lantern waiting for the little devils and princesses and ninjas-too-old-for-this-but-want-the-free-candy kids. After a bit Mr. Scotch joined me, and I enjoyed the rain just a little more. I thought about The Last Resort and the boys talking into the wee hours of the morning with the rain pattering on their leaky roof. In the end, I did not get too many more trick-or-treaters at my house than might stop by the boys’ camp. But I did make a significant dent in that candy. Be sure to vote. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed