At the summit of the Teeter-Totter Trail. Photos by Rick Showalter. At the summit of the Teeter-Totter Trail. Photos by Rick Showalter. Last Sunday, on yet another unusually cool morning, we decided to take Lucy for a walk at a nearby network of mountain bike trails appropriately called Skullbuster. Rather than staying on the abandoned roadbed as we typically do, we donned hiking pants in a vain effort to ward off ticks and chiggers and headed for the orange trail, a byzantine loop of crisscrossing singletrack that features behemoth oak and maple trees as well as the old Stockdell family cemetery. At one crossroads we decided to check out the Teeter-Totter Trail. I initially imagined the name referred to an undulating path with sharp up and downhill sections. Instead, it turned out to be a gradual uphill through both pastoral woodland and some slightly more open brushy areas. At one point we passed an old stone wall, evidence of a former homestead, which currently serves neither as property line nor rudimentary enclosure. A few yards farther up, at the highest point on the trail, we arrived at a small clearing where a simple bench had been erected among the towering trees. A few steps beyond the clearing were…two teeter-totters. I had not expected that the trail would lead me—literally—to teeter-totters or, as I always called them, seesaws. It was a moment of pure surprise and delight. They appeared rough-hewn but sturdy enough for two adults, so Rick and I tried them out. Lucy was quickly bored, so we took the intersecting path to Wyatt’s World, a trail full of laid stone ramps and log jumps to challenge the cyclists, and eventually found ourselves back on a familiar stretch of the orange trail. As we walked, I thought about how those teeter-totters had gotten there. Remembering the stone wall, I imagined a family in the early twentieth century constructing them to entertain a passel of children. That idea had evidently settled in my mind when Rick mentioned that just as Wyatt’s World was likely named after a central Kentucky cyclist with a penchant for treacherous downhills, he suspected a cyclist named Teeter had been inspired to construct the teeter-totters from leftover lumber as he worked with other volunteers to develop the trail system. His comment startled me. We had both stumbled upon the teeter-totters for the first time just moments earlier and, in that brief period, we had both quietly come to radically different conclusions about how they got there. My romantic mythology arose from my limited understanding of the history of the place, which I had concocted purely from the scant evidence left behind by long ago inhabitants. In my silent musings, those who built the trail system had happened upon a relic of another world. Seeing the same evidence, Rick concluded quite sensibly that those constructing the trail simply hadn’t wanted to lug unused lumber back down the trail and had had imagination sufficient to figure out an entertaining application for it. If a conversation hadn’t ensued, we would have left the trail carrying two immensely different interpretations of this site of human activity. I look to my friends with backgrounds in archaeology or anthropology to explain the human frailty this experience reveals. I will admit it has humbled me. Although I was still embellishing my romantic vision of farm children running toward the teeter-totters after a day of chores, I can imagine how quickly that initial vision might have congealed into “fact.” Can my experience, my understanding of what I observe, my conclusions be so errant from what may actually be true? How quickly I could have gotten to certainty—and been dead wrong. At that moment I realized how easy it is to create our own mythologies. And once we have created them, we are emotionally bound to them. We will not give them up easily. After listening to Rick’s unexpected interpretation of what we saw, I felt fairly quickly that his scenario was probably more likely than mine. But if my vision had had more time to gel, I might have been more stubborn. He might not have been able to change my mind, and I might have fought tooth and nail to defend the mythology I had created. I could imagine myself insisting on the validity of a baseless story I had simply told myself over and over. Perhaps this experience not only provided a much needed dose of humility. Perhaps it also provided a window into the empathy I currently lack to understand those who seem to have fallen under the spell of what I believe to be false interpretations of facts or experiences. I may never share their beliefs, but perhaps, if I were willing to set aside my own contrariness, I can better understand how they came under the sway of a mythology they so dearly want to believe.

6 Comments

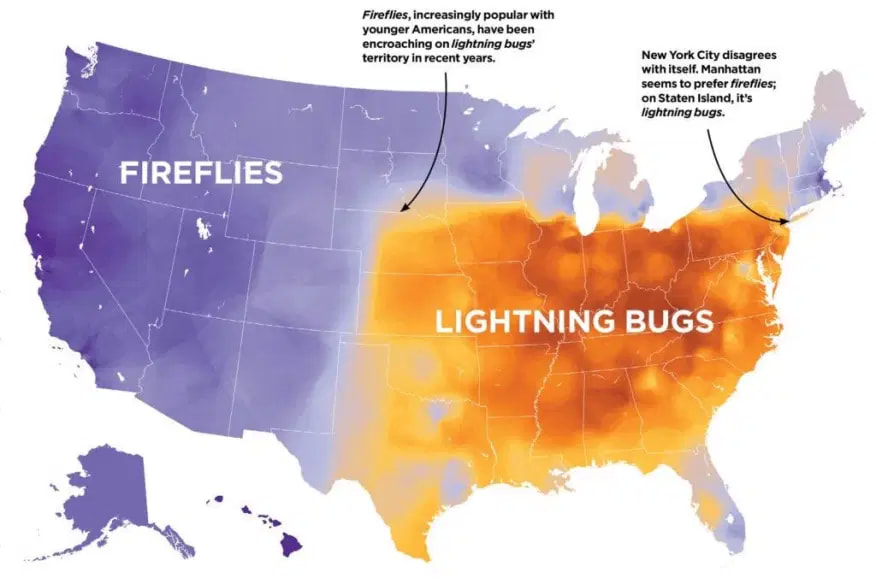

The creature in question. (Well, one of many: there are actually thousands of firefly species. Or lightning-bug species. Or whatever.) The creature in question. (Well, one of many: there are actually thousands of firefly species. Or lightning-bug species. Or whatever.) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, explores our relationship with a beloved emblem of summer. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. They dot warm summer nights like phosphorescent punctuation marks. They carry bioluminescent chemicals in their abdomens that produce a cold light, more like LEDs than Edison incandescents, to attract potential mates. Little children (and adults behaving like little children) enjoy chasing after them, catching them in hand and watching them glow on release. (I’ve been known to do this after a couple of beers.) What am I talking about? Lightning bugs, of course. Or fireflies. Or glow worms. Well, which is it? It turns out that it’s all three, though the first two names are now more common than the third. But it also turns out that what you call these creatures is, in part, dependent on the section of the country from which you hail. The following map recently appeared in an article on the Rochesterfirst.com Web site: This makes sense to me. I’ve called these beetles both names at different times but lean toward lightning bug. No surprise there, as Kentucky is smack dab at the center of lightning-bug territory. But I grew up in North Syracuse, New York, at the northern edge of the same region, and called them lightning bugs up there, too.

The article goes on to note an interesting coincidence. Firefly is more common in parts of the country that record more wildfires. Lightning bug is more typical of areas with higher frequency lightning strikes. The author correctly states that this is not proof of causation. But it is definitely intriguing. We get no help from John Goodlett on this topic. The bugs are never mentioned in The Last Resort. (Pud always was a plant guy, first and foremost.) What to call an insect may seem like a purely academic question, of little import to anyone other than linguists or entomologists. That notion would be mistaken, however. Sectional differences are an integral part of American history, with serious and sometimes dire consequences. These many differences—a true, organic form of diversity rather than the often forced and phony stuff that we’re being inundated with now—are gradually being rung out of our lives by the growing homogeneity of corporate-state culture. I like lightning bug but am okay with firefly as well. I hope distinctions like this one, and thousands of others, stick around for a while longer. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed