Central Kentucky scene (photo by Rick Showalter) Central Kentucky scene (photo by Rick Showalter) I’ve been reading the shockingly beautiful On Homesickness by Kentucky native Jesse Donaldson. In what has been called a hybrid memoir that includes elements of history and mythology, Donaldson writes about his yearning to return to Kentucky after marrying and settling in Oregon. Like many young Kentuckians, he couldn’t wait to leave the state to pursue his dreams elsewhere, and he landed temporarily in several different states across the U.S. Then, unexpectedly, powerfully, he began to succumb to an overwhelming homesickness. He writes, “I feel Kentucky’s draw like the thinnest of threads stitched into my heart—unspooled and fastened to a stake sunk into the marrowbone of home.” During a recent speaking engagement at the new Brier Books in Lexington, he confessed that he wrote the book in part as a plea to his wife to consider relocating. However, now that they are raising a daughter in Oregon, he realizes that that goal has become increasingly unlikely. After poring over my father’s journals, there is no doubt that Pud Goodlett was intensely homesick for Kentucky. He, too, had left his home state, although perhaps a bit more reluctantly, first to fulfill his military obligations and later to continue his education. Upon returning to The Last Resort after training at Camp Wolters, Texas, and Ft. Benning, Ga., he wrote “Coming home I was even more amazed at the wonderful countryside—HOME. Nothing can ever beat it.” As his academic career continued to hold him in rural Massachusetts, he chafed at his inability to move closer to home. When he learned about a promising opportunity at the University of Kentucky, he and his wife, Mary Marrs, joyfully began preparing for the move, while fretting about its projected cost. It is one of the few truly sunny portions of his second journal, which is filled with professional turmoil and angst. That makes the heartbreak he conveys nearly unbearable when he learns that the position will not be offered to him because the current staff member has decided not to retire. As a teenager, I remember learning how shocked some of Pud’s cousins had been when he chose to go out-of-state to complete his education. They had never left Kentucky and could not imagine why anyone would. At the time, that seemed laughably parochial to me. Now that I’ve read Pud’s most intimate thoughts at the time, I realize how well they knew him and just how much he suffered because of his choice. As Donaldson writes, “life takes from us the places we’ve known and we rarely return to root ourselves a second time.” But he also mentions notable Kentuckians who have returned following a time away. Readers of Kentucky literature are fortunate that Wendell Berry, Bobbie Ann Mason, Ed McClanahan and many, many others found their way home and chose to share their observations of their beautiful, mysterious, sometimes wacky, and sometimes damnably infuriating home. Kentucky seems to have a draw like few other states. Few leave without suffering a nostalgia that many times brings them home. If this nostalgia is indeed a sickness, modern medicine has yet to find a cure.

1 Comment

David Hoefer, second from left, author of the Introduction to The Last Resort, talks with Dr. Michael Hamm, professor emeritus of history at Centre College. David Hoefer, second from left, author of the Introduction to The Last Resort, talks with Dr. Michael Hamm, professor emeritus of history at Centre College. On Saturday I was on the campus of Centre College in Danville, Ky., for a book signing event. The previously quiet lobby and art gallery of the beautiful Norton Center became considerably noisier as more and more people arrived for the 11:30 alumni recognition ceremony. Folks were milling about the tables where a number of authors were prepared to introduce their books to the crowd. A robust-looking older gentleman and his smiling wife approached our table and picked up a copy of The Last Resort. I glanced quickly at their name tags, which identified them as members of the class of ’48 and ’46 respectively. I immediately recognized that they would be about the same age as some of the boys who visited Pud’s camp—which meant they might have a genuine interest in the book’s first-person account of a time they would remember. Before I could formally greet them, the gentleman looked at the author’s name and said, “Goodlett, huh? I used to know a Vince Goodlett in Frankfort.” I smiled broadly. “Well, that would be my uncle, the oldest brother of the author.” “One of the best attorneys of his time,” he continued. “With Hazelrigg & Cox, you know.” And thus began a wonderful conversation with this couple who still reside in Frankfort. With so many of their generation no longer with us, it was just amazing to stumble into someone who knew my uncle well, who had fond memories of Vincent Goodlett, who died in 1973. During the event that morning I was able to reconnect briefly with a number of other people who have danced through my life: classmates and professors and people I admired from afar. I also chatted at length with a few who were inspired by the work we had done capturing a piece of family history. So many of us have possession of stories or letters or diaries that we find fascinating and that we’re fairly certain other readers or history buffs would enjoy. Sometimes we just need a little nudge to take that first step toward sharing them. I hope the publication of The Last Resort will encourage others to dig into the documents their families have preserved. Day by day we’re losing an entire generation—a generation whose lives spanned incredible changes in our country and who played pivotal roles in both building and preserving this nation. I wish I had had more time to talk to the couple who stopped by our table and learn more about their own stories. I hope they enjoy reading about Vince’s younger brother and the close bond that existed between the two. At the next book signing, I think I’ll be more prepared to listen rather than talk.  Rice Crossing, October 2017, after a week of significant rain. (Photos by Rick Showalter) Rice Crossing, October 2017, after a week of significant rain. (Photos by Rick Showalter) A lot has changed in the last 75 years. I don’t need to detail that here. But I have occasionally wondered how Pud would respond if he suddenly appeared among us. Who’s driving all these big truck-like cars? When did every town start looking the same? What is everyone staring at, eyes lowered, as they walk along the sidewalk? Why will no one make eye contact? If he had the chance to head back to The Last Resort, however, he might be pleased to learn that the area near his camp on Salt River has not changed all that much. The property has new owners and the wooden cabin has been taken down by the ravages of time (although the limestone chimney the boys built is still standing). Coming from Lawrenceburg, he would pass a large commercial area he probably could never have imagined, as well as a high school, an elementary school, and a couple of subdivisions. But a few miles out, he would still recognize the entrance to Powell-Taylor Road and the remains of the rock quarry on the right. As he turned left on the road to the camp, he would see the cemetery on the right. To the left of the road, the river looks pretty much the same. And, sure, there are a few new houses along the road to the camp, but the character of the road has not changed dramatically. It’s still largely farmland. There are no subdivisions. The road has not been widened, even though it is now paved. That’s also true of Rice Road on the north side of the river. It still feels like a rural road you would expect to find much farther from town. In fact, the unimproved river crossing on Rice Road that Pud and his buddies used regularly to get to camp has not changed at all. Cars still have to drive across the slate river bed to get to the other side. There is no bridge. In the low-water summer months, you may see families there, cars or trucks parked in the river as they wade or hang out on innertubes or fish. But when the water level is high, traversing Rice Crossing can be extremely dangerous. It is frequently impassable. This is the type of inconvenience few of us experience in today's United States. But it puts a smile on my face every time I drive this road. In our fast-moving, unpredictable world, it gives me a sense of calm to know that some things have not changed. Some things are still good enough, just the way they’ve been for generations.

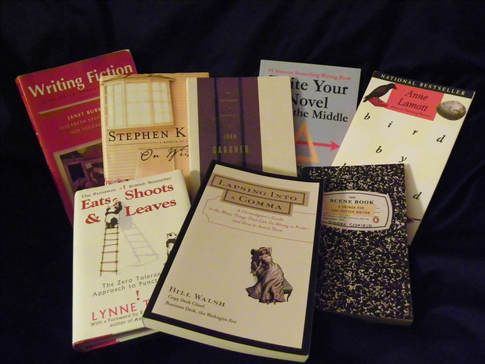

Sometimes it’s OK to slow down, to be forced to take the winding road, to simply enjoy the beauty of a spot without considering how it might be made better. Pud’s journal still presents a handful of mysteries that we haven’t been able to solve: names of people we could never identify, fishing regulations we couldn’t ascertain, even the precise source of the nickname “Pud.” During the early months of the project, perhaps the one that bothered me the most was our inability to identify that “cursed” Jack. For the most part, Pud’s entries reflect a generosity of spirit and a good-naturedness that may seem almost precious to today’s readers. Sure, there are flashes of annoyance, such as when the younger Boy Scouts bring too many supplies to camp and not enough blankets, or when Bobby plays the radio all night. But they’re always short-lived, and then the tone assumes the same equanimity that permeates the majority of the pages. And that’s why the one exception stands out, the one seeming fit-of-pique that Pud allows himself to express. On Friday, May 8, 1942, he writes: “Came to camp with Bobby and Jack (curses) at 4:30. The river is high and has a very peculiar yellow color.” And with that, the hint of anger is over. But who was this “Jack,” who had elicited such an uncharacteristic response? I asked everyone I could find. I asked my cousins. I asked the graduates of the long-defunct Lawrenceburg High School at their annual reunion. I asked the two surviving members of Pud’s core group of friends, Rinky and John Allen. Thankfully, as it turned out, no one could recall a “Jack” who would have been at the camp. It was enormously frustrating not to be able to identify who prompted Pud’s unrestrained reaction. Then one day, deep into the research process, I finally got to sit down with Bobby Cole’s son, Bob, at his house in Salvisa, Ky., not far from the site of the camp. I had a long list of questions for him. He had spent a lot of time on Salt River with his dad, and he certainly knew more than anyone else about the fishing holes, the neighbors, his extended family, and the stories he had heard about Pud and his father. I worked my way through my list, madly scribbling notes. Then I looked at him and asked, “Do you have any idea who Jack was?” And he didn’t hesitate. “Oh yeah, Jack was dad’s dog.” And there you have it. Never once had I considered the possibility that Jack was not a person. Jack was Bobby Cole’s dog who loved to frolic in the river, and thereby ruin the fishing for the two young men. On May 8, Pud was looking forward to a good day of fishing, but as soon as he saw Jack he knew the chances of that were slim. And, for possibly the only time in the journal, he allowed himself to document his frustration. As with nearly all facets of life, I finally had to accept that I wasn’t going to get answers to all of my questions. Some mysteries would remain. And perhaps that’s as it should be. The Last Resort was, after all, the boys’ private hideaway on the river. We weren’t supposed to have full access to all that went on there. But I sure am glad that Pud left behind a multi-pane window that lets us glimpse just a little of what those boys were up to. Special thanks to Bob Cole and his son, Evan, for providing these video clips.  I’ve been in a lot of writing classes lately, and one of the pieces of advice I’ve heard repeatedly is “As soon as you finish one project, start another one.” The point of this admonition, as I understand it, is not only to continually hone your craft but also to demonstrate to a potential publisher that you always have another book or article just weeks or months away from completion. Putting that into practice has proven to be a bit of a challenge for me. When The Last Resort was finally available for purchase, I was ready to kick back and take a breather. Granted, on that project I wore a lot of hats: I wasn’t the author, but I was an editor, the book designer, the operations manager, the financial manager, the website and software manager, the interviewer, the Anderson County expert (solely because of my family’s roots), and the general contractor, responsible for handling the contributions from various craftspeople (artists, photographers, and mapmakers, to name a few). Little did I realize as the book went to print how much time I was just beginning in invest in marketing. So, when I look back on it, perhaps I had good reason for wanting to celebrate what we had accomplished, instead of digging immediately into my next project. But other commitments I had made didn’t allow me to step away from the grind. About a week after the book was published, I started a nine-month partnership with a mentor who is helping me shape a novel about a very different character in my family’s history, my maternal grandfather. In many ways, that project is much more daunting for me. I don’t really see myself as a creative writer, and I’ve never written fiction. That alone would probably halt any reasonable person from taking on such a challenge. But I’m intrepid, if not very wise. And I had an incredible story fall into my lap, so I feel some responsibility for rendering it in a compelling fashion on the page. So now here I am, trying to juggle ongoing marketing responsibilities and my somewhat harrowing attempt at crafting a novel, plus assignments for my writing classes and the writing and editing I do part-time to earn a living. Some days I find myself leaping from one to the other every hour or even half hour. It can be wildly disorienting, and I wonder if anything is being done well. But I have to embrace this amazing opportunity I have created for myself. In part because of my wanton fearlessness—and thanks to a very understanding and encouraging husband—I am doing something many people dream about but never give themselves permission to pursue. I, on the other hand, never really saw myself as a writer, but somehow stumbled into this place. The one thing I have learned in my many decades on this earth is to welcome every unexpected twist in your own life story with enthusiasm and bravado. Who knows where it might take you? |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed