Every blog I post is a love letter to you. As words begin to attach themselves to a thought whirling around in my brain, I slowly recognize the emotions that are driving an insistent drumbeat. Therein lies the passion that provokes me to write. As I compose a piece—sometimes slowly and carefully, sometimes rapidly with abandon—I realize the subject of the post is nothing more than a vehicle for relaying how I feel. And what could be more intimate than sharing my inchoate thoughts, thoughts that I am just beginning to understand, with you? It’s dangerous, frankly. It’s reckless. It’s exhilarating. Nonetheless, I do it. I don’t always know if my tentative plea to connect with you has been successful. Did my message leap the synapse of time and distance and tingle your nerve endings? Did my words bring us closer? Or did they widen some invisible chasm that threatens to swallow them in its gaping maw? Sometimes you let me know I reached you. You send an email. Post a comment. Other times, I choose to believe my words prompted a slow simmer that may eventually awaken new awareness, without sparking a too-hot flame. Sometimes I learn that my cautiously expressed feelings are universal, or at least more widely shared than my ugly self-absorption would have me believe. Sometimes I learn that my words help you sort out your own thoughts. It has bothered me lately that I seem to have nothing to say to you. No thoughts have bumped rudely around in my head, demanding to be let out. I’ve tried to summon some sort of passion, but I know I cannot press. I must let it develop on its own. Perhaps a year of loss has finally taken its toll, a summer of disruption has knocked me out of rhythm. Too much death, near and far, both inevitable and avoidable. Too much illness, both inconsequential and critical. I can’t find my balance. I have lost my words. They may yet return, and I hope you will again allow me to reach out to you, needy and raw, and share what I’m feeling. By doing so, I have learned, I slowly begin to understand myself. But right now I hate my own voice. It’s irritating. Whiny. Tinny. Uninteresting. Perhaps that will pass. Perhaps not. Meanwhile, I hope you’ll be patient with me, like a faithful dog. We’ll see if my passion for communicating will reignite. Know that I’m grateful for your loyalty, dear reader. I honor the time you spend with my words. I long to reach out to you with more thoughtful discourse. And I hope that when we do reconnect the frisson will startle us yet once more and prompt unexpected discoveries.

11 Comments

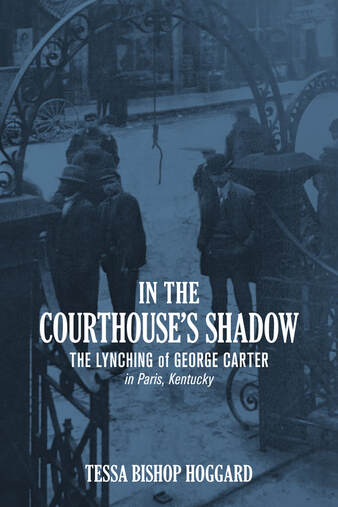

Words can be challenging. Words can be challenging. I suppose it should be comforting that it was a small group of friends much younger than I who shared their common insight. “Words are hard,” they had all agreed, laughing, as one of them couldn’t find the word she was searching for as they congregated for breakfast after a morning walk. When they told me this story a little later, standing in front of my table at the Lexington Farmers Market where I had three books displayed that co-opted tens of thousands of those sometimes intractable words, I smiled knowingly and looked at my friends a little closer. One is a visual artist and professor. Although words are not her preferred medium of expression, I am certain she is articulate and profound during classroom discussions about creating and interpreting art. One is an engineer with a natural talent for managing people, who solves complex problems and coaxes her colleagues in the direction she needs them to go. One is a teacher who compassionately interacts with teenagers from widely diverse cultures, students whose first language is rarely English. In their professions, words are their currency. All are expert communicators. They are quite comfortable expressing themselves. I imagine they rarely think about how fluidly the words come…until a cantankerous one goes missing. These days, I seem to have a particular problem recalling proper nouns: names and places, titles and characters, famous people and family members and longtime acquaintances. Shortly after my conversation with these three remarkable women, a former boss of mine—someone I reported to for four years—stopped by my table and chatted for several minutes. A week later I finally remembered her first name. I still haven’t come up with her last. (If you detect this happening when you next encounter me, please don’t think that means I don’t cherish our relationship. It just seems that my brain has made room for the mountains of new trivia necessary to navigate the modern world by archiving information I would choose to keep close at hand. Too bad my rather headstrong cognitive processes don’t consult me before making these sometimes critical decisions. On the other hand, as I glance around my cluttered office, perhaps that’s for the best.) I also recognize that words’ elusiveness is part of their charm. Ask any writer. Words can indeed be hard. Hard to come by. Hard to conjure. Hard to differentiate. Hard to define. Hard to know. Hard to let go. Hard to lasso for a specific need. If words were easy, we wouldn’t take so much pleasure in wrestling them into cohesive, lyrical patterns. Words can also be hard to hear, if we’re not inclined toward the truth, or if we’re feeling unusually burdened. And they can simply be hard, if their intent is to bruise. Sometimes I seem to have too many words. I can’t get to my computer or to a pad of paper fast enough to capture my thoughts. In those instances, I’m typically just letting off steam about some issue that has me riled up. Or perhaps I’m sorting through an emotion that blindsided me. Occasionally I feel I’ve distilled some human experience in a way that may be worth sharing. Sometimes I say too much when I should have kept my mouth shut. Knowing when to use your words can be hard, too. Those of us who love words, who ache for more time to immerse ourselves in the carefully chosen words of others, who can disappear into a world fabricated by a word artist—we’re the lucky ones. Words are our friends. We’ll put up with a little petulance now and then, even as we sense their smirks as they refuse to come out of hiding.  Tessa Bishop Hoggard has written a compelling book about the people and events surrounding one of the more than 350 extrajudicial lynchings in Kentucky. Tessa Bishop Hoggard has written a compelling book about the people and events surrounding one of the more than 350 extrajudicial lynchings in Kentucky. On May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer in his mid-40s, evidently decided that 46-year-old George Floyd’s alleged infraction of passing a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill should cost him his life. Three other officers watched as Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds—even longer than we had originally understood. Despite exhortations from the other officers and the citizens standing nearby, despite Floyd’s pleas to let him breathe and his invocation of his recently deceased mother, Chauvin kept his knee on Floyd’s neck until he was no longer breathing. And then he kept his knee on his neck for another three and a half minutes. Chauvin’s defense attorneys have posed a number of counterarguments during the initial days of the trial, including that Floyd had illicit drugs in his system, that he had a heart condition that contributed to his death, and that his physical size made him a threat to the officers even after he was handcuffed and lying face down on the ground. Over the past 10 months we have learned a bit more about George Floyd and his family. We know he was a college athlete who struggled to stay in school and struggled with addiction. He spent some time in prison. We know he had moved from Houston to Minneapolis to try to turn his life around. During the trial, we saw his fiancée describe his kindness when he had first approached her at the Salvation Army where he was working security. For months we have witnessed the courage and the oratory and the passion of Floyd’s siblings and his cousins. We’ve seen the confusion of his bright-eyed young daughter whose father is now famous. He has come to feel like someone we knew, like someone we might encounter joking around at a corner market just like Cup Foods. That’s what Tessa Bishop Hoggard has accomplished in her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow. Through diligent research, she has fleshed out the story of one heretofore anonymous young Black man who was lynched in Paris, Ky., in 1901 after being accused of a minor crime. Like George Floyd, George Carter had previously run afoul of the law but was trying to settle down with his young family and build a good life. Like Floyd, Carter never had a chance to claim his innocence or plead his case. A group of white men with power in his community decided that he should pay with his life for a crime that we have no evidence ever even occurred. We also learn that others who endured a fate similar to Carter’s were described in the press the same way, whether accurate or not: “burly negroes over 200 pounds.” As in Floyd’s case, physical size—or perceived physical size—justified illegal actions. In Hoggard’s book, we learn about Carter’s family, their hopes and their dreams, and what happened to them after he was killed. We learn the fate of his two young daughters. We also learn about the family of the white woman who identified him as the man who had assaulted her, a crime that was originally reported as an attempted purse snatching. We learn about the fate of her eight-year-old son, who witnessed the assault and helped the sheriff identify Carter as the assailant. We learn that George Carter, like George Floyd, was a father, a son, a brother—a human being. He was not just a statistic of early 20th-century racial injustice. Just as George Floyd was not merely another victim of 21st-century police brutality. This is a problem our nation obviously has not solved. On March 18, during a House Judiciary Committee hearing on anti-Asian American violence and discrimination, Republican Congressman Chip Roy of Texas said, “We believe in justice. There are old sayings in Texas about find all the rope in Texas and get a tall oak tree. We take justice very seriously. And we ought to do that. Round up the bad guys. That's what we believe." Afterwards Roy refused to apologize for his choice of words and doubled down on the language. As columnist Charles Blow recently wrote in the New York Times: “It is hard not to draw the through-line from a noose on the neck to a knee on the neck. And it is also hard not to recall that few people were ever punished for lynchings. Motionless Black bodies have been the tableau upon which the American story has unfolded…” Those who witnessed George Floyd’s murder have testified about their sense of helplessness at the time and the enormous guilt they still carry. Some videotaped the crime and shared it with the world in horror. Those who discovered George Carter’s body hanging in front of the courthouse on that cold February morning tarried at the scene and took photos, seemingly proud of the town’s latest trophy and the message it sent. Is that a sign of some progress in the last 120 years? Are we finally beginning to push back on these unforgivable acts of oppression and subjugation? What would we do if we found ourselves witnesses to such a crime? Would we simply stand by and watch, as the two doormen in New York recently chose to do as a 65-year-old Asian American woman was being assaulted on the sidewalk in front of their building? Or would we find the power to act? In 1901, George Carter was only 21 years old when he was lynched. I wonder if he, in his final moments, silently called for his mother. Murky Press is proud to offer In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky through Amazon or by contacting Murky Press directly here. We encourage you to recommend the book to others or post a brief review on Amazon to help spread the word.

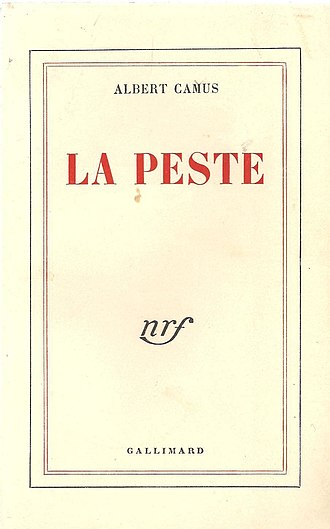

The first edition of Albert Camus’ “La Peste,” or “The Plague,” published in 1947. The novel is a fictional telling of a 20th-century epidemic. Its “truths” seem all too real to contemporary readers. The first edition of Albert Camus’ “La Peste,” or “The Plague,” published in 1947. The novel is a fictional telling of a 20th-century epidemic. Its “truths” seem all too real to contemporary readers. Back in December, in the awful year of our Lord 2020, I happened to flip on a news program just as author Salman Rushdie pronounced, “Lies are a way of obscuring the truth. Fiction is a way of revealing the truth.” Having taken numerous classes and read many books on fiction writing in recent years, this concept was not novel to me. (Sorry…) Nor is it original to Rushdie, of course. Writers Albert Camus and Jessamyn West, for example, famously used nearly the same words to relay the same idea. But I hurriedly scribbled the words on a pad of paper that I’ve learned to keep in front of the TV—my oracle for inerrant wisdom—and they’ve rolled around in my consciousness ever since. This week our nation will be subjected to yet another impeachment trial of Former President Donald J. Trump (or “the 45th President Donald J. Trump,” as he evidently prefers to be addressed). He is in this predicament once again because of his lies. He lied about the fairness of the election before the election, and he lied about the results of the election afterwards. He also pressed other people, such as Georgia election officials, to lie for him. Many, many people believed his lies, and, ultimately, his lies led to the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6. People died, and other people’s lives were threatened. Trump obviously felt it was to his advantage to “obscure the truth.” If he is not convicted, if he never faces any further accountability for his lies or the damage they caused, what deterrents will there be for other elected officials not to lie to further their agenda? Or to cry “Fraud!” every time they lose an election? In fact, our country seems to be so awash in lies that I’m not sure how we ever find our way back to the truth. Perhaps that’s why Rushdie’s comments have stayed with me. Some of the most powerful—or memorable—fiction tells the stories of ordinary people who find themselves in horrific situations: war, poverty, imprisonment, abuse, persecution, pandemics, social or political upheaval. It’s by temporarily inhabiting these fictional characters, seeing their world through their eyes and ears and emotions, that we can begin to understand their truth. It’s not until we actually feel ourselves in that battle or in that degrading circumstance, or we feel that hunger or those taunts or that pain, that we begin to fully grasp their reality. It may seem odd at first to think that a made-up story taking place in a made-up world is where we may logically find the most truth. But perhaps that imaginary incarnation permits greater honesty. Or perhaps it helps remove our own prejudices so we can see things more clearly. Which leads me to ask: Will we have to wait until some great works of imagination are written about these dark days—these days spent watching our democracy teeter on the brink—before we are able to fully untangle all the lies? Or can a nation of disparate peoples with disparate experiences and viewpoints finally, through sheer will, recognize a common truth so we can heal this country? This week the impeachment managers will carefully present all of the facts they have collected, drawing the clearest picture they can to support their contention that the former president incited the insurrection. But can they “reveal the truth” in a way that the majority of our citizens, let alone two-thirds of the Senate, will accept it? We’ve already seen most of the evidence. Many of us watched it play out in real time. But, still, we don’t agree on the appropriate response. The truth remains elusive. Fiction may be our last hope.  This week I’m offering something completely different. Friday night, after trying—fruitlessly—to keep up with the news relating to the COVID-19 cases swirling among our government’s highest officials, I woke in the middle of the night with the following words running through my brain. I finally got out of bed and wrote them down. You will see, clearly, that I have no training as a poet. I know nothing about proper forms or meter or rhyme schemes. So I hope you’ll read this as my nocturnal wordplay, an example of what happens when my subconscious wrests control from my conscious thought. I have not altered what I captured during those feverish moments. I have not allowed subsequent news or insights to inflect these thoughts. I offer this simply as one citizen’s subliminal attempts to make sense of the harrowing world we live in. As the Dominoes FallI wake up and wonder:

Was it all a dream? This fever-pitched Swampiness holed up inside my head For what seems like millennia But was only long enough To topple democracies And eradicate futures and pasts, Fury and white-hot hate Scorching our throats and Trampling our dignity Until one by one they started to fall, Hubris humbled by truth, Surrendered to a force So tiny it arrived Undetected by the Armies forming in our streets, Long guns tossed over shoulders, Chants rending the night, A force too subtle for their Rigid minds, too potent for their Star Wars defense. We had thought it a scourge, Nature doing battle against Man’s unconscionable crimes. As we watched helplessly Thousands succumb—a million-- Innocents lost, Our heroes, our warriors, Our suckers Who shared this precious gift and Delivered us, our nation, From certain death. I have never considered myself creative. I’m a dogged rule-follower. I can read music but couldn’t improvise if you put a gun to my head. I can follow a recipe but rarely experiment in the kitchen. I could never dream up a clever Halloween costume, and I eventually came to hate a holiday that I had loved as a child because of it.

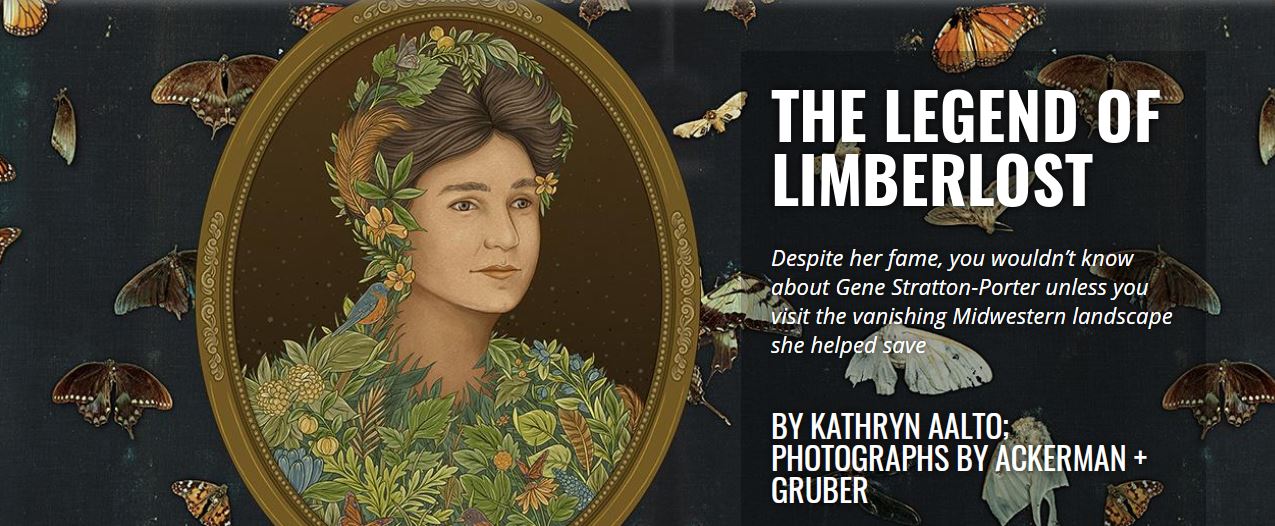

I have absolutely no artistic ability: I can’t draw or paint or sculpt. I have no interest in or talent for what some might call crafts, including scrapbooking or photo collages or needlework of any type. In fact, in high school I tested in the bottom tenth percentile in spatial aptitude. So much for a career as an architect. But recently my cousin Charley shared an article that made me rethink my capacity for being creative. In fact, it made me realize that it may well have been my bent toward creative thinking that hounded me throughout my sketchy professional career. For me, every problem was simply a puzzle to be solved. What I didn’t understand was that solutions that seemed obvious to me were perhaps unimaginable to others. Was it my fearlessness, my ability to envision a positive outcome, my willingness to tackle something new in unexpected ways that frequently made my co-workers so ill-at-ease? In the article “Secrets of the Creative Brain” (The Atlantic, July/August 2014), Nancy C. Andreasen shares the results of decades of research into some of the great creative geniuses of our times, both in the arts and the sciences. Some of these individuals’ common characteristics may not be surprising, but they hit home for me. For example, she found her subjects were “adventuresome and exploratory,” and they were willing to take risks. Check. She added that “Creative people tend to be very persistent, even when confronted with skepticism or rejection.” Check again. Once I’ve decided something is possible and laid out a plan for getting there, I don’t back down. I’m heading to the finish line, whether you’re coming with me or not. Andreasen also relays that many creative people have broad interests across many disciplines, and they are good at making unexpected connections. That, for me, is the essence of good writing—connecting disparate things in surprising ways, using language or metaphor to awaken the reader’s senses. I’ve always been interested in lots of subjects, but I know little about any of them. In a typical day I bop from immersing myself in politics to paddling on the lake and admiring the wildlife to researching a technical computer issue to reading a novel about World War II to trying to understand a poem that a friend has shared with me to romping with the dogs in my neighborhood. I hate routine. I love variety. I never want to do the same thing twice. In graduate school, my department chair railed against "dilettantes," declaring he would have none in his classes. I would laugh and wonder, “What else are we?” I recall sitting in fiction writing classes recently and wondering how on earth writers come up with the story lines and the scenes and the conflicts and the dialogue necessary to create a compelling narrative. Up to that point, everything I had ever written had been based on facts, whether I was preparing a technical manual or promoting an art event or writing a faculty member’s bio. I’ve come to realize that what I sorely lack is imagination. Not creativity. Many have asked me about the subject of my next novel. I swear that I’m a “one-and-doner.” Starting with the realities of a person’s life let me cheat the first time. How could I possibly invent a story and a plot and the characters whole-cloth? I simply don’t have the capacity to do that. But perhaps I will begin to think of myself as creative. I recognize that I tend to look at things a little differently than others. I am fearless. I don’t mind choosing the untrodden path. I embrace making choices that might bewilder others. I might even propose outlandish courses of action. Sometimes they work. Sometimes they don’t. But nothing will hold me back if I think I have a shot at accomplishing it.  A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? A spring cove on our lake. A few days after this photo was taken, there were two types of purple wildflowers and one yellow blooming boldly on the forest floor. I could not name any of them. Did I really see them? Recently I wrote that I now have two books in my “catalog.” As I worked on the second book, it frequently occurred to me what strange bedfellows they are: a first-person narrative by a still innocent 19-year-old naturalist driven to document the flora and fauna inhabiting his halcyon getaway; and an almost gritty tale of a man stripped of his innocence who leaves his home behind and wanders from one commercial/industrial area to another with hardly a nod to the natural world around him. I love to spend time outdoors, and I sometimes feel ill-at-ease in the city. I am the daughter of a naturalist, a scientist who could identify any specimen he encountered during an amble through the woods. I, however, was never disciplined enough to fully develop his prodigious skills. While I can identify many native woodland trees and common birds, the names of most wildflowers, grasses, and garden plants are a mystery to me. And I truly regret that I can’t recognize bird songs. For years I was certain that that shortcoming alone disqualified me from writing a novel. Successful fiction is full of lush details of blooming flowers and the bees hovering around them. Or a prairie of grass and the animals that live there. Or a midnight sky and the constellations that awe us. In “Seeing the World Around Us,” I mused about the importance of being able to name a thing for that thing to fully enter our consciousness. Without that ability, we are blind. We look past the diversity of life all around us. We come to consider ourselves the all-important foreground spotlighted against an indistinguishable background. I still believe that my deficiency seriously weakens my ability to provide the sensory details readers need to feel a place. The plants and critters who share our space define our world, perhaps even define a part of who we are, even if we can’t always recognize them. So when I had a story I just had to share with others, and a fictional narrative seemed the only way to tell it, perhaps I was fortunate that that tale largely unfolded in cities or confining indoor spaces—steamy kitchens, tiny apartments, the birthing bedroom. I stole a few opportunities to place my characters outside in the fresh air. In retrospect, it’s clear that my characters, like their creator, look outdoors when they are seeking balm for a troubled soul, or a place for reflection. I was reminded of my inability to fulsomely describe a lush plein air scene as I read a recent article in Smithsonian magazine, sent to me by my cousin Barbara, about an acclaimed “naturalist, novelist, photographer and movie producer” whose name I had never encountered: Gene Stratton-Porter, born Geneva Grace Stratton in Wabash County, Indiana, in 1863. Perhaps I’m showing my woeful education by admitting I was not familiar with her, since both Rachel Carson and Annie Dillard cite her as a keen influence. I have not read any of her work—fiction, nonfiction, or poetry—but I can only imagine the richness of the natural scenes she portrayed. Her intimate knowledge of the Limberlost wilderness she wrote about, gained during countless days exploring on horseback and waiting quietly for the perfect photo, must make her tales of plucky young girls and strong women come alive. Stratton-Porter evidently brought to her writing both my father’s ability to document the natural world and my desire to tell a personal story. She had both the scientist’s eye and the writer’s imagination. In addition, she had the patience of a photographer, willing to devote the time needed to capture the most arresting photo, and then to indulge in the careful writing necessary to relay that vivid image, and her human response to it, in words. Amid all her talents, Stratton-Porter most relished her simple sensory responses to the world she discovered while wandering outdoors: “Whenever I come across a scientist plying his trade I am always so happy and content to be merely a nature-lover, satisfied with what I can see, hear, and record with my cameras.” I, too, am a nature-lover, not an academic or a trained naturalist. As life seems to slow for all of us, perhaps this is the time I need to devote to not only admiring but learning to name the beautiful things that catch my eye and restore my soul. The author of the Smithsonian article, Kathryn Aalto—a landscape historian and garden designer, as well as an author of several books—is herself a master at describing natural detail. Her first paragraph immerses the reader in northeastern Indiana’s Loblolly Marsh Nature Preserve, a small part of the vast swamplands that Stratton-Porter spent her life documenting: “Yellow sprays of prairie dock bob overhead in the September morning light. More than ten feet tall, with a central taproot reaching even deeper underground, this plant, with its elephant-ear leaves the texture of sandpaper, makes me feel tipsy and small, like Alice in Wonderland.” Stratton-Porter also recognized early the danger of mankind’s desire to tame the land for our own use. As Aalto writes:

“Twenty years before the Dust Bowl of the 1930s, Stratton-Porter forewarned that rainfall would be affected by the destruction of forests and swamps. Conservationists such as John Muir had linked deforestation to erosion, but she linked it to climate change: “It was Thoreau who in writing of the destruction of the forests exclaimed, ‘Thank heaven they cannot cut down the clouds.’ Aye, but they can!...If men in their greed cut forests that preserve and distill moisture, clear fields, take the shelter of trees from creeks and rivers until they evaporate, and drain the water from swamps so that they can be cleared and cultivated, they prevent vapor from rising. And if it does not rise, it cannot fall. Man can change and is changing the forces of nature. Man can cut down the clouds.” Nobel Prize-winning writer Czeslaw Milosz is often quoted as saying, “When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished.”

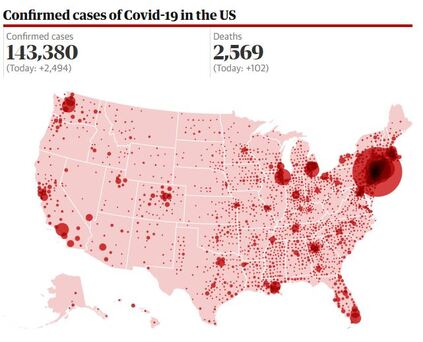

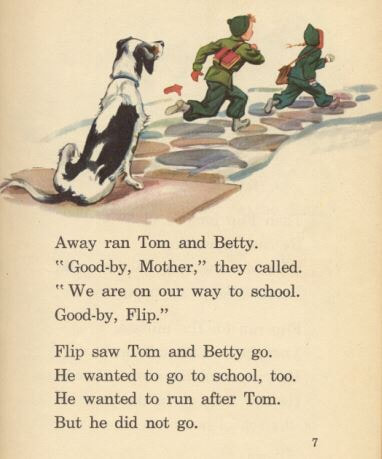

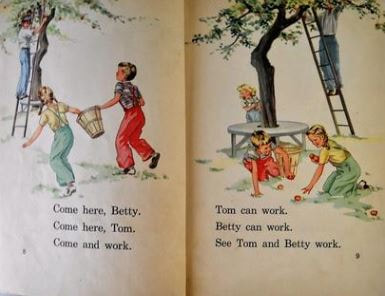

I stumbled across this quote recently when reading about the one-woman play based on Elizabeth Strout’s novel My Name is Lucy Barton that opened earlier this year in New York. I chuckled. As I have pursued publishing two books about family members—one about my father who died when I was seven, and the other about my maternal grandfather whom my mother never knew—I have frequently wondered about the propriety or even the dangers of writing about family. In my case, I did not set out to write a “tell all” book or to reveal any uncomfortable truths about my personal experiences. In The Last Resort, I essentially let my father do the talking, and I was cautious not to include in the excerpts from his Harvard Forest journal any details that I thought might be construed as too personal or too negative toward those in his orbit. Nonetheless, I did want to reveal just enough to make him feel more fully human to readers. Next Train Out is, of course, a novel. It is a fictionalized telling of my grandfather’s life. I relied on the facts I had at hand to discern possible motivations or character traits that would lead him to take the actions he did. Some may consider the details of the story scandalous or horrifying. I simply view them as the facts. Nearly all the people who populate these books are long gone from this earth. That distance gave me some comfort and perhaps the license to share these stories. At the same time, I felt some responsibility for making my representation of the characters as truthful as I could, given the limitations of my knowledge. I would sometimes ask myself, “If Effie Mae’s descendants were to read this book and somehow recognize her in the telling, will they feel I have maligned her memory?” I don’t think so. There is one character in Next Train Out who is portrayed as a sort of villain, which I don’t believe is truly accurate. But I needed a foil for Lyons, and he was a good choice. I checked with his great-grandsons—my cousins—twice to be sure they would be OK with my fictional representation. They assured me I didn’t need to worry. Another cousin called recently to say how delighted she was to find her grandfather and other relatives identified by name in the novel. It made the whole story come alive for her. She probably didn’t remember that I had called her late last year to be sure she was OK with my using their real names. During that conversation, she offhandedly shared some physical and personality traits of those family members with me, which I dutifully incorporated into the story. So it can indeed be dangerous to have a writer in the family. Or in your circle of friends. But, as Anne Lamott wrote in Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life: “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.”  We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. We’re all connected now. The coronavirus knows no borders. Data as of 30 Mar 10:25am EST. Source: Johns Hopkins CSSE. It occurred to me recently that I’ve already heard from people in six states who have read Next Train Out: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Florida. I know that individuals in Georgia, Ohio, and New York have ordered the book. I have been thinking of the book as a “regional” novel, perhaps because of its settings in Kentucky, Ohio, and the Maryland coast. So I’m pleased to see its reach extend to New England, the Upper Midwest prairie, and our nation’s southernmost state. Though I confess that all of these readers have some sort of connection to Kentucky—however tenuous—I want to believe nonetheless that my limited data indicate the book has a wide appeal. That little survey of Next Train Out readers also made me realize that even during this period of social isolation we can share common experiences with far-flung friends and relatives, as well as people we’ve never met. I’ve delighted in the conversations and email exchanges I’ve had with those of you who have read the novel and have reached out to ask questions or offer critiques. We may not be able to meet for coffee or lunch, but we can still connect remotely and discuss something of interest to us both. In a much broader sense, I’m reminded that, while we’re in isolation, reading affirms our affiliation with greater humanity. Reading prods us to feel profound human connections with the characters in a book, however dissimilar we believe they are to us. While this worldwide pandemic might force us to become more self-centered in our daily routines, reading coaxes us to imagine ourselves in someone else’s situation. Faced with that character’s challenges, how would we respond? What would we do? How would we feel? In a time when the empathy of America’s citizens is once again being severely tested, it’s critically important that we look beyond our own perhaps small inconveniences and annoyances and consider the sacrifices and the heartaches of those around us. It’s impossible to turn on the television or check the news without seeing heart-wrenching stories of people who are ill, who have lost loved ones, who are tending to the medical needs of the sick without the necessary life-saving equipment, who are going to work every day to provide us with the goods and services that remain essential, who are struggling to patch together a precarious financial situation, who are wondering if the business they built will survive another month, who are fretting about their children’s education, who are struggling to stay healthy, both physically and mentally, during our voluntary home incarceration. How equipped are we, individually, to acknowledge their struggles? Do we fully recognize the need to change our habits to possibly keep someone else safe? Are we willing to make those little sacrifices? Reading widely helps train us for moments like these. It teaches us empathy. And compassion. It reminds us how small our own little world is. It reminds us that there are others with needs so much greater. In a recent article in The New Yorker, Jill Lepore, a professor of history at Harvard, wrote: “Reading may be an infection, the mind of the writer seeping, unstoppable, into the mind of the reader. And it is also … an antidote, proven, unfailing, and exquisite.” In order, potentially, to reach an even wider audience—to spread “the contagion of reading,” as Lepore describes it—I have now released a Kindle version of Next Train Out. If you or someone you know prefers to read books on a tablet, e-reader, or other device—whether for convenience or to easily enlarge the size of the text—the Kindle version might be a good choice. It’s also an economical option for those watching their budget during these uncertain times. If you have read Next Train Out, I humbly ask you to consider writing a brief review of the book on Amazon. That may help other readers stumble across the title as they’re looking for a new diversion during our nationwide quarantine. I remain grateful for your interest.  Who didn’t learn to read alongside Tom, Betty, and Flip? Who didn’t learn to read alongside Tom, Betty, and Flip? As many of us find ourselves with time to pick up a book, Peggy Cooper, of northern Kentucky, recalls first learning to read. Her ruminations may even inspire you to start putting words on a page. Peggy is the co-editor of Celebrate a Community, reprinted by Murky Press and available now from Amazon. It was 1960. I’d been ill and out of school because of some childhood illness. When I returned to school, there was catching up to do. Mrs. Johnson brought me to the front of the class so that we could do some work together while the rest of the class did other things. In the front of that classroom on a table perfectly sized for a first grader stood a huge book, a book that was taller than I was. I was going to learn to read. I knew my numbers and letters. I liked hearing stories and looking at the pictures in books. I liked school and Mrs. Johnson. She had taught my father when he first attended the one-room schoolhouse just south of Chasetown. He could read before he even went to school because he’d watched and listened and learned alongside his brother, John, who was two years older. Because he already knew first-grade learning, my father managed to skip that grade. I didn’t understand what I was supposed to do. It always helped to see other children do things first. Cousin Barbie, best friend and confidante, sat in the desk in front of my desk at school. She lived in town. She was wise in the ways of the world. She always knew what to do. We would talk and whisper and plan and play together. She was not at the table in the front of the classroom with me. I was lost, in more ways than one. Mrs. Johnson pointed to the picture in the book. The boy, Tom, was running. Yes, I could see the picture of Tom running. There were big black letters too. S-E-E. Yes, I knew those letters. What did those letters sound like? They sounded like an ess and an eee and another eee. How did they sound together? What did that mean, sound together? And what did Tom have to do with those letters on the page? Mrs. Johnson had been teaching for many years. In some way that now seems magical, she helped me make the connection between those letters on the page and how those letters could be put together to make words that told a story. I don’t remember how long she worked with me that day or over the next several days; I know it was a struggle. Mrs. Johnson knew how to help: SEE! See Tom. See Tom run! Then Betty joined the story, and Susan, and Flip, the dog. I could read! Triumph! Now I am putting letters on a page to tell stories myself. The stories, and the writing, are often like that experience of learning to read—a struggle to create meaning from a jumble of things that don’t seem to be connected. Sometimes the stories are about people who have lived and worked together and had a life before I was even born, remembered because it, the story, or they, the people, were significant in some way. Sometimes the stories are memories from my own life, savored because they were important to me. Sometimes the story evolves out of a photograph or a document, again, saved for a reason, and sometimes saved across generations. The essence of the story is the feeling it provokes, and often the meaning is caught up in the reason that the history, or the memory, or the photo or document, was saved. But, how to find that meaning, put it into words, and then share it? Feelings are elusive—and sensitive—things. Meaning is equally elusive, and personal. And the personal is, oftentimes, private, delicate, and special. A decision must be made—share or not? Struggle sums up the process. I’m still working on the triumph. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed