With my cousin Sandy Goodlett, who died in April 2021, my cousin Joe Moore, and his wife, Jean. In Atlanta, August 2015. Photo by Robert Goodlett. With my cousin Sandy Goodlett, who died in April 2021, my cousin Joe Moore, and his wife, Jean. In Atlanta, August 2015. Photo by Robert Goodlett. When I was a sophomore in high school, my mother decided for a number of complicated reasons to send me to a boarding school in Virginia. Nestled at the base of a mountain in the Shenandoah Valley, it was the perfect place for me. I could canoe, camp, ride horses, play tennis, and even join a synchronized swimming team. Classes were tiny: typically five or six students, maybe 12 in my biggest class. We got to know our teachers personally. After overcoming initial loneliness, I made some friends by the end of the year. Sadly, that was the last year the school, which had been in operation for nearly 100 years, was financially able to stay open. A number of my classmates chose to attend similar schools in the area. For some reason, inexplicable to me now, I decided to try something completely different: a large urban school in the swanky north end of Atlanta that accepted only a few boarders, largely international students. It was an academically competitive school, and I devoted hours every night to homework, rarely finishing before the wee hours of the morning. The Southern norms and mores mystified me. I joined the marching band and the volleyball team, but otherwise completely isolated myself. I was miserable. I became anorexic, starving myself both to avoid solitary meals in the cafeteria and in a vain attempt to exert some control over an immensely painful situation. When I dropped to 82 pounds, even the women who cleaned the dorm were asking me about my health, expressing genuine concern. I batted away their inquiries. At my previous school, I couldn’t avoid knowing that a number of the girls purged after meals. One in particular, a friend of mine whose room was across the hall, was a competitive figure skater from Wisconsin. She didn’t come back the second semester, and I heard through the grapevine that alcohol and bulimia had landed her in the hospital. The public was just becoming aware of eating disorders and their toll on young women and their families, but I couldn’t imagine myself falling victim to such self-abuse. Then my circumstances changed. My dad’s first cousin, Joe Moore, lived in Atlanta, and he and his wife, Jean, periodically brought me to their house or took me sightseeing around the city. They gave me a taste of normalcy. I was deeply grateful to them for taking me in when I most needed to feel welcome somewhere. I doubt I was able to express at the time what their kindness meant to me. At Christmastime that year, my mother recognized the severity of my illness and didn’t let me return to Atlanta. With her quiet, non-pushy supervision, comfortable in my own home, my health improved. A few years ago, my cousin Sandy Goodlett helped me reconnect with Joe, his brother, John Allen, and their sister, Jane. We made a couple of trips to Atlanta and Owensboro, Ky., and relished the family stories they could share with us. Having lost my father at a very young age, I was always thirsty for details about my dad from those who knew him best. On Sunday, January 9, Joe’s wife, Jean, died of complications from Covid and increasing dementia. She was fully vaccinated but still vulnerable at 83. As I work through my own sadness, I realize it’s tied to the kindness she extended to me in a time of real distress. A new year, more time to grieve. This virus is not done with us. We’re still losing more than a thousand Americans each day. Each victim leaves behind a loving family and friends. We know this. It sounds trite. But we should not forget it. We should not get complacent. And we should not decide it’s OK to sacrifice the aged and the vulnerable so we can blithely go about our lives without disruption. We must take the simple steps that we can to limit the virus’s spread: get vaccinated and boosted, wear a mask, avoid large crowds. That is not asking too much.

4 Comments

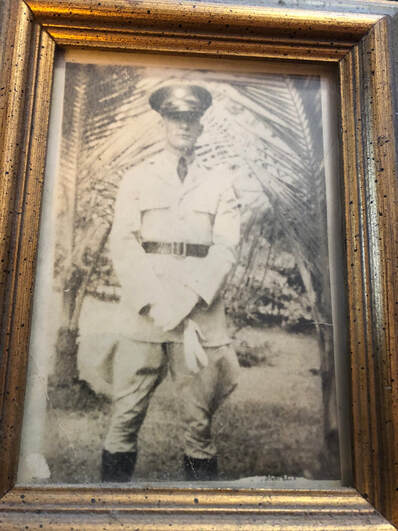

The author’s father, Corporal Joseph P. Anthony, circa 1940 in Hawaii. The author’s father, Corporal Joseph P. Anthony, circa 1940 in Hawaii. Joe Anthony, of Lexington, Ky., wonders whether Americans have what it takes to defeat our 21st-century enemy. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. During the 1940s, do you think our parents and grandparents would sometimes complain to each other? “I’m so tired of news about the war. Can’t we talk about something besides the Pacific Front or Allied landings?” I’m sure they did, occasionally, but they knew the war was center stage. Covid is our war. It doesn’t matter if we’re “over it.” Our enemy, Covid, is endlessly crafty, energetic, and vicious. I know. I recently spent 16 days in the hospital and nine days in a rehabilitation facility after contracting the virus. I was fully vaccinated and boosted, and it nearly broke me. As in all battles, it’s ourselves that matter even more than our opponents: our vanities, our fears, our prejudices, our malice. If we can manage ourselves, we will vanquish the enemy. George Will, the conservative columnist, wondered if our country, as constituted now, could win the Second World War. I wonder, too. It isn’t only the reluctance to sacrifice for the common good; it’s the refusal to believe the credible. Millions indulge themselves with fantastic speculation backed by no evidence and sometimes no logic and reject that which comes with freight-loads of scientific proof or that which they witnessed—re January 6th—with their own eyes. That refusal to acknowledge basic reality breaks down community, too. We can’t even get to the point of disagreeing. A sub-group of Americans in the ’40s, die-hard America-Firsters, pushed the theory that FDR had been behind the attack on Pearl Harbor. But they were called nuts by the huge majority. Now there is no “nut” theory that doesn’t get a hearing and eventually, it seems, a substantial following. Our parents and grandparents may have grumbled, but they collectively pulled themselves together: gathered scrap, rationed, and sent their sons to fight. They accepted hard truths, facts they didn’t like. They knew the news wasn’t always going to be good and didn’t reach for a scapegoat to blame. Well, not usually at least. And when the dreaded telegraph arrived, they grieved but knew their sacrifice went beyond themselves—went out to the country they loved. They got some comfort from knowing that. Though death is always solitary, the country they sacrificed for came back to them in a collective embrace. We love the same country. And if we truly love that country, it will love us. Can we do less than our previous generations? Can we even imagine loving our fellow Americans? |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed