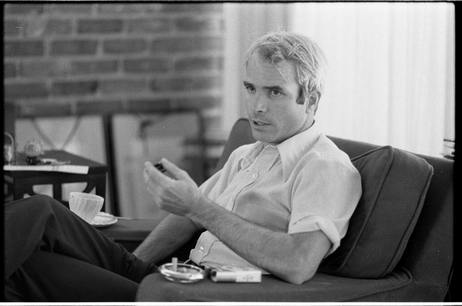

Lt. Comdr. John S. McCain during an interview after his return to the U.S., April 24, 1973. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Lt. Comdr. John S. McCain during an interview after his return to the U.S., April 24, 1973. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. After reading last week's post Seductive Silence, Tim Cooper, of Oakdale, Minn., has been thinking about how a liberal arts education could encourage the empathy and resilience we so desperately need. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Like many Americans, I was riveted to the television during the services for the late Sen. John McCain. It was a brief, and it appears now ephemeral, moment when we were reminded of the heroes among us who have been willing to put country above party or personal interests. My favorite McCain story related how a prisoner in the cell next to McCain’s at the Hanoi Hilton used a surreptitious tapping code to teach McCain the Robert Service poem “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” McCain’s daughter Meghan shared how he later recited the somewhat grisly poem to his future wife on their first date. That was my first glimpse into the Renaissance man who was John McCain. I learned that his favorite author was Hemingway and his favorite novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. I learned that McCain regularly read novels and enjoyed writing. While in the U.S. Navy, I attended classes at the Naval War College. The highlight for me was a lecture by Admiral James Stockdale, a man who had endured eight years as a prisoner of war, also in the infamous Hanoi Hilton. During the lecture, Stockdale revealed the key to his survival: His study of moral philosophy—particularly the Roman Stoics—while a student at Stanford had provided food for his mind during those endless days of tedium and fear. He was able to draw from his own intellectual reserves to provide the discipline and resilience he so desperately needed and avoid succumbing to the darkness. As president of the Naval War College, Stockdale later instituted classes in philosophy, literature, and history. For him, study of the liberal arts was not just a path to enlightenment; it could well be the key for another young serviceman’s survival. It struck me that these two national heroes, either by their own habits or by their professional influence, were evangelists for the value of education in the humanities. We all face times when we need to draw from our knowledge or understanding of the human condition to survive a struggle that seems poised to drop us to our knees. Sadly, a quick perusal of recent news articles reveals that the classic liberal arts curriculum is being relegated to history. Colleges in the University of Wisconsin system have eliminated English, sociology, political science, and history majors from their campuses. In their stead, these universities offer business, science, engineering, and computer technology centers. In Lexington, Bryan Station High School has restructured its curriculum as the Academies of Lexington, an initiative dedicated to preparing students in grades 10 through 12 for future careers, careers that range from electrician to chef to computer programmer to paramedic. As I understand this new initiative, all curricular content is filtered through the lens of the student’s career aspiration. Meanwhile, Eastern Kentucky University has made its marching band a peripheral “activity” separate from the school of music, eliminating its academic affiliation. My father, a man who abandoned hopes of a pro baseball career to become a professor in the music department at EKU (until his premature death in 1988), always promoted the marching band’s democratic pull, its ability to connect students from a variety of majors and interests and expand their experience with the arts. These insidious changes also reached the parochial school where I taught for two decades before retiring in June. Students entering this institution are now encouraged to declare in middle school whether they would like to work toward a “business certification” that would be attached to their high school diploma. The goal is that, by taking business classes, students will attain what Bryan Station identifies as the ability to see real world applications in what they learn in the classroom. But what have these students lost? At my former school, signing up for the business classes extinguishes the option of taking band, chorus, art, or photography. By devolving the marching band into a student activity, EKU has lessened the connection non-music majors had to an acclaimed music school. And by emphasizing the utilitarian nature of learning, Bryan Station’s program has obviated the concept of learning for learning’s sake. My best friend during my undergraduate days at the University of Minnesota was a young man from rural Wisconsin who was interested in literature, theater, classical music, blues, jazz, and pop-culture. Kurt was also a business major. During his last two quarters at the “U,” Kurt contacted numerous companies about employment. Caterpillar Corporation called Kurt to arrange an all-day interview at their corporate headquarters in Peoria, Ill. Kurt asked me to drive down with him. After his very long day, I asked Kurt how the interviews had gone. He shook his head and responded, “It’s the craziest thing. They never once asked me about business. Instead, they asked about what I read, what I think about, what plays I had recently seen, whether I volunteer and why, and so on.” A week later, when a representative from Caterpillar called to offer him the job, Kurt asked about the peculiar nature of the interviews. The representative responded simply and directly: “We can train anybody about our business, but we cannot teach people to be well-rounded.” Readers of The Last Resort will recall that Pud Goodlett read Walden and Ridpath’s history, but also works by humorist James Thurber and contemporary popular fiction. They were all outside his academic interests in plant geography and ecology. In The Last Resort, are we seeing the last of an era that encouraged Renaissance men? Have we relegated all that Pud and my dad were to myth, and have we replaced their world view with one regulated by market considerations? Have Senator McCain, Admiral Stockdale, and my friend Kurt become quaint examples of an ethic that no longer holds sway? I am distressed that not only have colleges and universities become training grounds for careers, but so, too, have high schools. I am distressed that many future business leaders, politicians, and academics have not been exposed to a liberal arts education and have, instead, become technocrats in their own professions. And I am most especially distressed that the understanding, empathy, and, dare I say it, behavioral standards acquired from embracing moral philosophy, literature, and the creative arts seem to have been lost to the dictates of economic empowerment.

0 Comments

Mary Marrs Goodlett at her 70th birthday party on Oct. 26, 1991. She died 16 days later on Nov. 11. Mary Marrs Goodlett at her 70th birthday party on Oct. 26, 1991. She died 16 days later on Nov. 11. I can almost feel my mother rolling over in her grave. On October 11, 1991, exactly one month before she died, I remember finding her in the recliner positioned next to her bed, riveted to the television. She was watching Anita Hill testify before the Senate about the sexual harassment she had endured while working for Clarence Thomas. My mother was a political junkie. She had watched endless hours of the Watergate hearings in the 1970s. According to the journal my father kept in the 1950s, they had both closely followed the Joseph McCarthy hearings. So I suppose it shouldn’t have surprised me to see her following every detail of the shocking testimony. But my mother was also in a losing battle with cancer, and I remember thinking it felt like a sad way to spend your final days. Her cancer had made this articulate, intelligent woman nearly mute, so it wasn’t possible for her to tell me what she thought about the spectacle. But it was discouraging for me to think that this might be her last image of the country her husband, already dead 24 years, had fought to defend. My mother had worked in male-dominated businesses. She had been a chemist at two different Seagram’s distilleries. She had worked for the Navy in Hawaii during World War II. She had worked at a large university. She had worked for state government. I have to imagine that she had suffered sexual harassment at some point in her life. I can only hope it was not as degrading as what Hill so bravely described. Of course, my mother had never mentioned any incidents of harassment to me. Nor had I ever told her about the sexual assaults I had experienced as a young woman. It never occurred to me to tell her—or anyone else, for that matter. I was fortunate in that my experiences did not seem to haunt me. Like so many, I felt I had somehow been at fault, although deep down I knew that was not true. I suppose I found the incidents embarrassing, a sign of my own weakness or naïveté. So I simply buried my memory of them and moved on. Until I watched candidate Donald Trump brag about his penchant for sexually assaulting women. That moment brought everything back. To regain control over my own stories, I seethed in an op-ed about the presidential candidate’s behavior. I’m in the majority, of course. In a January 2018 online survey sponsored by the nonprofit Stop Street Harassment and reported by NPR, 51 percent of women stated that they had been victims of unwelcome sexual touching. I’ll admit that number seems low to me. The survey also found that “81 percent of women and 43 percent of men had experienced some form of sexual harassment during their lifetime.” In part because of the Anita Hill hearings, managers in workplaces across the country now receive regular training on how to handle accusations of sexual harassment. Most of us recognize that it is a pervasive problem that we are still struggling to address. Most of us understand that it is most commonly an abuse of power and has very little to do with sexual titillation. Recently, we have all watched as women, spurred by the #MeToo movement, have found their voices and started naming the men who have victimized them. There has been a wave of courage, of provocative charges against people known and unknown in positions of power. In the last few days, a new movement, #WhyIDidntReport, has emerged in response to one of President Trump’s tweets. And now, amid this backdrop, 27 years after Anita Hill attempted to educate the largely white male U.S. Senate about sexual harassment and its ramifications, we are once again watching a nominee to the U.S. Supreme Court deny allegations of sexual assault. The accuser is once again female, educated, professional. I had hoped that the process for investigating the allegation might be handled with more sensitivity and more honesty than we have witnessed so far. It seems we’re hearing the same old excuses. The powerful men have not relinquished control. The kid gloves that they initially so carefully displayed have now come off and it appears to be fair game to attack or bully or belittle the accuser. Why does it feel like nothing has changed? I think of my mother staring intently as our Congressional leaders exposed their vile inhumanity and their naked self-interest, and I am once again ashamed.  A snake I stepped around during a spring hike in 2014 near Yahoo Falls in McCreary County, Ky. Photo by Rick Showalter. A snake I stepped around during a spring hike in 2014 near Yahoo Falls in McCreary County, Ky. Photo by Rick Showalter. The first time I recall encountering a snake in the wild was at Girl Scout camp. I was 7 years old. My father had died about three months before and, at my uncle’s urging, my mother had moved what was left of our family from Baltimore to central Kentucky, closer to relatives. While staying at the rambling farm house of my aunt and uncle awaiting our move into a new home, my father’s mother—my only grandparent—died. My mother’s aunt and closest confidante suffered a stroke. There seemed to be no end to the calamity. I loved staying with my cousins at their farm. But I was unmoored from all that I knew. My father’s absence seemed to confuse me less than the prospect of starting life over in a new town. I hated leaving my friends. On the other hand, my dad—a professor during the academic year and a researcher for the U.S. Geological Survey during the summers—hadn’t been around much anyway. Did I miss him? I wasn’t sure yet. As summer arrived, my cousins were preparing to go to camp. My mother and aunt (Charleen, the boys’ ready rescuer at The Last Resort) evidently thought it would be a good idea to send my sister and me, too, perhaps so we could be around children our age in a more normal environment, or perhaps to allow my mother a little privacy to grieve. I was technically too young to attend the two-week camp, but the administrators had given me special permission. Everyone kept a watchful eye on me. I was not only the youngest camper; I was most certainly the tiniest. But no one needed to worry. I loved every minute of it. I loved being deep in the woods of Morgan County. I loved sleeping outdoors in a tent modeled after a Conestoga wagon. I loved swimming in the brownish green water of the lake. And I particularly loved the hikes along the mountain trails. So when one of our counselors first pointed out “Blackie,” the camp’s “pet” black racer, I was mesmerized. He was enormous—at least five or six feet long in my memory. It was a lighthearted moment. The 8- and 9-year-old veteran campers around me ooohed and ahhhhhed and called to him affectionately. Blackie took all the commotion in stride. I was smitten. I became that child who always volunteered to handle snakes that were brought into the classroom. At home, I gently shooed the garter snakes out of the way of the lawn mower or the hedge clippers. I can’t remember if we saw any other snakes that particular summer, although I encountered several over the succeeding years. (The image of the heavy rat snake coiled around the top of the latrine just above the seat is burned in my memory.) And I was fully aware that during every hike at least two counselors carried “snake sticks” and hatchets in case we came across a less companionable snake that needed to be disposed of for everyone’s safety. All of these memories came to my mind recently after having yet another conversation about snakes with two friends who share a sincere fear of the reptiles. A large corner of their consciousness seems to be devoted to their phobia. During our conversation, I wondered aloud way I reacted so differently. After brief reflection, I’m sure it’s because snakes were first introduced to me as friends, family even. Important wildlife that we should not disturb. That we should respect. During a recent paddle around our small lake, I experienced yet another flashback to Camp Judy Layne. I tucked my lightweight canoe into a cove deep in the woods, and the heavy vegetation and woodland smells transported me to my favorite childhood camp. After a dreadfully long stretch of dark and dreary days here in the Bluegrass, brilliant sunlight illumined the black oak leaves and the purple ironweed. As I paddled out of the cove, I could see bluegill swimming just beneath the surface as if they, too, had been longing for the warmth of the sun. Several Great Blue Heron swooped and cackled at me, warning me away from their supper. Dinner-plate sized turtles didn’t bother to leave their posts on downed logs, daring me to disturb their sunbathing. Perhaps, at some unconscious level, I learned at a tender age that the woods welcome us when our spirit has been wounded. That escaping into the woods can soothe the soul. The abundance of life there somehow gives back just what we need. Our personal afflictions can’t alter nature’s rhythms and cycles. Even the snakes have a role and a certain majesty. And somehow that comforts me rather than frightening me.  Photos by Rick Showalter. Photos by Rick Showalter. My parents were enthusiastic bourbon drinkers long before craft bourbons and celebrity master distillers. They were loyal to reasonably-priced Kentucky bourbon that soothed the rough edges of the day or amplified the conviviality of a small gathering. As Kentucky natives, they were proud to offer the state’s signature elixir to friends and colleagues in Maryland and Massachusetts. I imagine for them it served as an emotional tie to the home they felt estranged from but so longed for. So it was not surprising to learn that John C. Goodlett, only two years removed from an extended bout of homesickness as he was shuttled around Europe fulfilling his duties as a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, would, in 1948 while a graduate student at Harvard University, write a paper titled “Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey.” He was still a long way from home, and perhaps he hadn’t yet fully reconciled why he had chosen to continue his studies at such a distance from all that he knew and loved. What is surprising, however, is that the Harvard Botany Library still has a copy of that paper in its stacks. David Hoefer, author of the Introduction to The Last Resort and archaeologist extraordinaire, recently unearthed this relic during a routine search for books related to my father. Unfortunately, he also learned that the document is not available through interlibrary loan. My curiosity piqued, I picked up the phone to find out how I might access this bit of my father’s legacy. It turns out that all of the holdings at Harvard’s collective Botany Libraries are non-circulating. I’ll have to make a trip to Cambridge to learn just how my father managed to write about bourbon from a botanist’s perspective, and perhaps why this work has been housed in one of the university’s libraries for 70 years. The young lady who took my call was kind enough to pull the document from the shelves. She confirmed that what was identified as a “book” in the online card catalog appeared instead to be something more akin to a research paper. Nothing on the title page ties it to a particular Harvard class or professor or explains the thesis or genesis of the paper. Obviously, bourbon is distilled from a number of plants—corn, rye, barley—so it’s not too far-fetched to imagine why the young grad student chose this topic for research. One can also imagine the department professors getting such a kick out of the subject that they made the paper available to their curious, nonabstemious colleagues by placing it in the library. And somehow, either by neglect or fond oversight, it’s remained lodged in its somewhat incongruous home for decades. Someday I hope to make the trek up the East Coast to check it out.  This unexpected discovery took on more meaning when The Last Resort was recently reviewed by Steve Flairty in the Annual Bourbon Issue of the Kentucky Monthly magazine (September 2018). It seemed fitting that Pud’s journal about life along Salt River had found a temporary home among the articles extolling the burgeoning bourbon industry in Kentucky. It would have been hard for Pud to write about the Lawrenceburg environs in 1942-43 without mentioning the Old Joe and Ripy Brothers distilleries. In a contemplative moment in February 1943, he describes the two distilleries looming on the horizon as familiar geographic and economic markers of the county’s industry and history. “Took a stroll across Mr. Holly’s* this afternoon. Went by the pond where I saw several robins, killdeer, and meadowlarks. I walked up along the old rail fence to the ridge and up through the redbud thicket to the crest of the hill. I just sat there for an hour and a half and looked around. I could see for miles—Woodford and Shelby and Mercer Counties, Ripy Bros. and Old Joe. Today is just like spring with bird songs everywhere.” *Mr. Holly’s: Mr. Holly Witherspoon’s property on west Broadway, which included the site of the current high school and stretched north to Route 44. Pud went to school with members of the Dowling and Ripy and Bond families. They were his friends. He understood the role bourbon played as an economic engine for the county. In his handwritten notes on the “History of Anderson County”—which he kept in the same University of Kentucky loose-leaf notebook where he compiled the camp logbook—he inserts a brief but telling allusion amid more detailed information about the county’s founders, its courthouses, its industries, its churches, and its role in the Civil War: “pop. 1870—373. Since 1818—50 distilleries.” You can’t talk about Anderson County history without talking about bourbon. And it’s nearly impossible to recall a Goodlett family gathering without thinking about the bourbon that was poured. I expect the Johns Hopkins professor would have been tickled—or possibly mortified—to know that the paper he wrote about Kentucky bourbon as a first-year grad student is still available to curious botanists in 2018. I hope he would be happy to know that, in that same year, a book about his wanderings along Salt River would be mentioned in a magazine devoted to his favorite Kentucky beverage. Reading The Last Resort has inspired Tim Cooper, of Oakdale, Minn., to reflect on what it means to put words on paper and how meeting an esteemed poet in a neighborhood bar at age six awakened his poetic sensibilities.

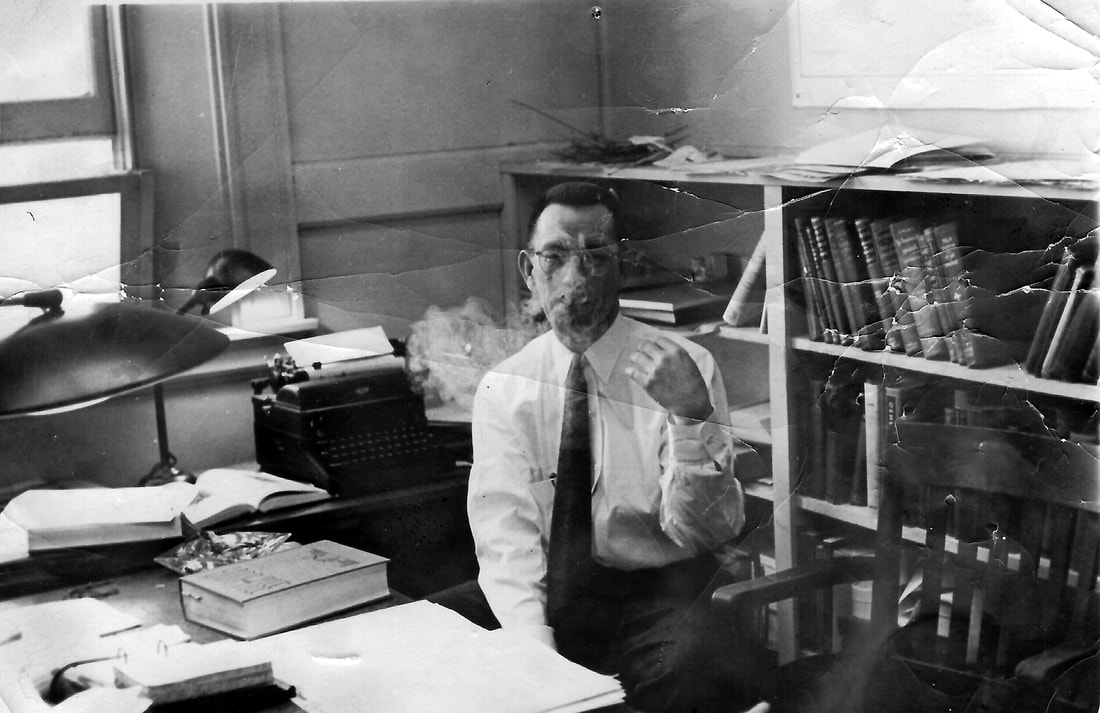

I have been thinking about essays. The etymology of essay—from the French verb essayer, meaning “to try”—incorporates the idea of experimenting with something, or attempting something new. Most essays delve into new ways of thinking about a subject, sometimes playing with a new narrative technique or voice. In the end, an essay is a thought experiment, an attempt to gain a greater understanding of oneself and one’s position in the world. Dedicated readers of “Clearing the Fog” are well aware of the disparate voices that cascade through this blog. David Hoefer applies his analytical bent to subjects as diverse as Steinbeck, fishing, and Pud’s cars. Bob McWilliams, Roi-Ann Bettez, Joe Ford, and others lead us to consider “a portion of unexamined existence,” as James Agee described his subject in the preface to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. I suspect they would all tell us that their responses to Pud’s writing, their observations, are simply personal mental calibrations elicited by the descriptions of life at The Last Resort. Agee goes on to say that his compilation of his stories and Walker Evans’ photos depicting the lives of several families in rural Alabama during the Great Depression “is a book only by necessity. More seriously, it is an effort in human actuality, in which the reader is no less centrally involved than the authors and those of whom they tell.” Likewise, Goodlett incorporated maps and drawings and lists of flora and fauna in his camp journal for his own reference, but perhaps also to draw any future reader into the experience of life at the camp. In its published form, The Last Resort, too, “is a book only by necessity.” I am currently rereading Charles D’Ambrosio’s phenomenal collection of essays, Loitering. One of D’Ambrosio’s essays—indeed, my favorite—is entitled “Degrees of Grey in Philipsburg.” It is a marvelous explication of Richard Hugo’s poem by the same name, and much like The Last Resort, it incorporates photography, notes, and the entire poem within its frame. It is Agee’s “effort in human actuality” in the best sense of that phrase, and it prompts me to relate a personal story. I must have been six or seven years old. My father was a visiting professor at the University of Montana, and we lived in Missoula. I love to recall that I had a mountain as a backyard. In those days, there wasn’t much protest when an adult brought a child into a bar. My father, and many others at the university, was pulled into the orbit of a rural, working class bar just outside Missoula. After teaching and giving private music lessons all day, my father would round me up and head to the Milltown Union Bar for a beer and conversation. There, late one afternoon, my father engaged a rather portly, balding man in intense conversation. I have no idea what they talked about. But after finishing his beer and getting us in the car, I apparently burst into tears. My father asked me what was the matter, and I could only respond that he had just spoken to the saddest looking man I had ever seen. Years later, when he reminded me of that story, my father also let me know that the man to whom he was speaking was Richard Hugo, poet-in-residence at the university, and now one of the most highly regarded poets our country has produced. His poems “Degrees of Grey in Philipsburg” and “The Milltown Union Bar” remind me of the portion of my youth spent in that region of graying, abandoned towns. If I could tell this story correctly, if I could write this essay properly, you would see an empty glass of beer in front of you, and you would choke on the acrid cigarette smoke. A poet would be sitting next to you, spinning lines. And the actuality of that world would prompt you to reconsider your own. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed