How I’ve spent my summer marketing Next Train Out. Photo by Rick Showalter. How I’ve spent my summer marketing Next Train Out. Photo by Rick Showalter. As traditional book fairs, author readings and, yes, book launch parties remain taboo, digitally savvy authors come up with creative ways to alert likely readers to their new books. The rest of us rely on friends, family, and colleagues to spread the word. Once the pandemic tightened its sticky little fingers around our collective throats, I pretty much gave up on marketing. I tried to focus on the blog, just to stay in touch with all of you. But I largely threw up my hands and said, “It’s God’s will.” Then I sat on my butt and ate bonbons. Slowly, however, as the initial shock of the lockdown lifted, the wheels of the old network began to grind. Thirty years of job-hopping started to pay off. A couple of folks I exchanged pleasantries with during my working days felt sorry for me and offered to help. First, Tom Eblen, formerly with the Lexington Herald-Leader and now the literary liaison with the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning in Lexington, Ky., reached out to me about doing an online reading to post on the Center’s Facebook page. Being the Luddite and contrarian I am, I’m not on Facebook. But I figured millions are, so surely two or three potential readers might become bewitched by the tale of Lyons and Effie Mae. I grumblingly agreed. After a couple of technical glitches, I managed to submit a seven-minute reading that suited his purposes. Then Tom Martin poked his head up from all the reporting the pandemic had generated for his weekly radio program on WEKU, Eastern Standard. Tom and I had planned to do this interview in April, but waiting until July gave me plenty of time to rest up before I had to perform again. Tom is a consummate interviewer—and an excellent editor. He can make anyone sound good, thank goodness. I know some of you caught the original airing of this interview on July 16. Now I figure if I sit patiently in my office—or on my dock—maybe another opportunity or two will come. Perhaps I’ll even sell a couple more books. Meanwhile, I’ll continue to lean on the excuse that there’s not a damn thing I can do to market this book during a pandemic. Coming upOn Thursday, July 30, at 11 a.m. on WEKU’s Eastern Standard, Tom Martin will present his remarkable summary of the conversation I had on July 15 with George Carter’s great-nephew, Jim Bannister. Listen to a preview. If you can’t catch the original airing, it will be available from Eastern Standard’s archives afterwards. I’ll write more about this experience for Clearing the Fog soon. That post will include links to the WEKU broadcast and to various newspaper articles about the conversation.

0 Comments

The beautiful Eastern Kentucky mountains. Photo provided by Joe Anthony. The beautiful Eastern Kentucky mountains. Photo provided by Joe Anthony. Joe Anthony, of Lexington, Ky., writes about how we are all the same—yet different. My wife and I and our 14-month-old daughter moved from New York’s Upper West Side to Hazard, Kentucky, in August 1980. Culture shock is what people gasp when they first hear that. Culture shock. I’m trying to think what they mean by that term. I’ve written a couple Appalachian novels and some stories where I play with the outsider/insider theme—showing how different expectations, different stereotypes, and different ways of communicating all make for an unexpected mix. Perhaps that’s culture shock. You expect certain things, certain reactions—or you don’t expect them and you get them. Did I know I was in a different place when I first moved to Hazard? Not really. Of course, there were the mountains. And accents. But I had taught in Brooklyn. You want accents? Spanish, Russian, Inner-city Black, African, and so on. At least Hazard’s accents were more or less the same—though deep in the county, places like Bulan, Kentucky—they were a little hard on the ear. But even then, you just needed a pause to understand. Like old fashioned-long-distance telephone calls. “Oh, that’s what he said.” So a place with accents—like Maine—only with mountains. How pretty. Look how the fog catches in the valleys in the morning, how it coats the rivers. But just a different part of America. The same people. A school of thought exists, a philosophy, a theology, that all people are the same. I’ve lived my life on that premise, and my writing, both on Appalachia and on race, center around that idea. But I’m not sure. Sometimes the foreign is so distinct that one wonders: how do I understand this? My first inkling that I was in a different place was the wary friendliness I encountered. I gradually understood that they had an idea of a New Yorker that didn’t match who I was. Brash self-confidence wasn’t my style. A certain cognitive dissonance occurred as they tried to adjust what they saw with what they expected. On the other hand, they expected me to fit them into stereotypes. But they again underestimated how ignorant I was: I didn’t know the stereotypes. I only learned the stereotypes after I had seen the reality. That’s not the natural order for embracing stereotypes: they really can’t take root. Of course, I understood quickly when I’d be invited to insult Appalachians as in “You must think we talk terrible.” I had taught English in inner-city Brooklyn. I thought Appalachians’ English their English. But I could sense the hurt beneath the lead-in query. My first real lessons in living in a foreign place were in finding that the way between two places is not necessarily a straight line: e.g., asking for something. For a small class, I had to ask all of the registered students if they had any problem with a changed time. I asked each one, personally, all twelve. No problem, all twelve answered. So I changed the time. One hundred percent. Each of the twelve had a major problem: a conflicting class, a ride home missed, a child that needed to be picked up. All of them. But I had asked, I wailed. Here’s what I think happened. I am not New York arrogant (I hope) but I am New York direct. Yes or no? Problem or not? I was ready for a no answer, but they perceived, correctly, that I wanted yes. So they said yes. Were they lying to me? No. They gave me soft yeses. Yessss. An Appalachian soft yes is a New York no. I would have known that if I had spoken the language. I would have pursued the question with “Are you sure?” and maybe then I would have heard of the child, or the class, or the ride. Maybe not. If it hadn’t been that all twelve students had problems, two or three would have kept quiet and quietly dropped. Better that than an unpleasant conflict. My New York students, stereotyping here a bit, wouldn’t have hesitated to tell me the facts—and maybe abuse me a bit for even asking. I would tell my classes in Hazard that they were much more complicated in their communication styles than any New Yorkers I knew. They’d laugh and not quite believe me, but it was true. I’d think: what do they mean by that? Where are they coming from? In my first novel, Peril, Kentucky, “playing” off Hazard, Kentucky, my main protagonist is a well-meaning New Yorker who plows ahead with her decent intentions—doing some good but so oblivious to where she is. Here are my words, she always seems to be saying. They mean this. They always mean this. How could they mean something else to you? I’ll say them again. Listen this time. Terrible things happen. It’s not all her fault. None of it is morally her fault. But if she had been culturally humble, perhaps some of it could have been avoided. “I don’t care to,” is the fun expression that sort of captures the foreign place my protagonist, Linda, and I both found ourselves in. In Jersey, it means you don’t want to do it. You want to play ball? “I don’t care to.” So my shock showed on my face when I asked someone to pass the salt and I got, "I don’t care to.” OK. You’re right. I should use less salt. Or. Do you mind if I reach? “I don’t care to.” Of course, it means the exact opposite in Kentucky: I don’t mind at all doing what you ask. Almost everyone I know from the East has that story. I don’t know that it’s just a verbal tic. I think it might indicate a whole frame of communication that is different. In Jersey, we might respond with a “no problem” or “sure” or, more likely, silence and the salt. But in Kentucky, at least Eastern Kentucky, relationships were more like a dance with structured steps. And if you skipped those steps, or if you shorthand them as in my class time question, you wouldn’t get a full answer, or a coherent one. You got a sign that the conversation was happening on a different plane. I got almost three books out of that ambiguity so I’m not complaining. So much more to say about culture shock: smiles that weren’t invitations in, but gates that kept you out. I haven’t mentioned the very different ideas concerning solitude, community, and isolation. But this is enough for now.  Birding might surprise you. A Red-Winged Blackbird in flight near Camp Last Resort, 2015. (Photo by Rick Showalter) Birding might surprise you. A Red-Winged Blackbird in flight near Camp Last Resort, 2015. (Photo by Rick Showalter) David Hoefer of Louisville, Ky., the co-editor of The Last Resort, offers an antidote for our trying times. The last several months have brought us the unsatisfying spectacle of a nation of 325 million people devising on-the-fly strategies to outwit a virus. Yes, there is a novel pathogen on the loose and, yes, certain groups, mostly the elderly and other persons with compromised immune systems, do appear to have a heightened risk of serious infection. What remains less clear is the actual extent of the threat to other segments of the population. The public-health response has evolved over time—remember gloves sí, masks no?—but one persistent feature has been the need to close up the populace indoors, away from others of our kind. This has proven problematic because modern humans—Homo sapiens—are profoundly social creatures. Efforts at selling “virtual communities” as replacements for flesh-and-blood gatherings are almost laughably off the mark. In reality, the antisocial practices of “social distancing” play to the worst aspects of American culture: the tendency to produce isolated individuals amusing themselves with trivial pursuits while failing at healthy, long-term relationships with family, friends, lovers, and neighbors. The longer we drag this out, the more likely unintended (and negative) consequences become. Be like PudOne sensible alternative to exile-at-home is the Great Outdoors. It’s becoming increasingly clear that fresh air and sunshine have been underutilized in our often-panicky response to COVID-19. Hiking, biking, picnicking, boating, fishing, and hunting are all good reasons for going outside, where the Earth’s ultimate limits remain hugely liberating, when compared to the four snug walls of our houses and apartments.

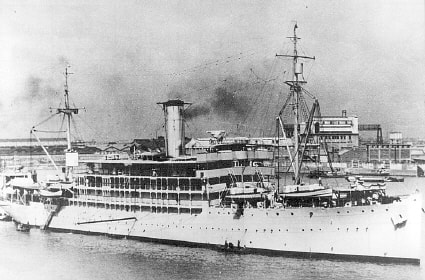

We used to understand that outdoor activities were beneficial for us. That was certainly the case for Pud Goodlett and the gang in The Last Resort. They went to the trouble of constructing a home-away-from-home, as a means of ready access to the varied and gracious Salt River environment of Anderson County, Kentucky. The cabin itself luxuriated in nature, with spiders, birds, weather, and even lightning intruding on occasion. This was no place to hide from the external world, calculating defenses against every potential risk to comfort and safety. Though Pud was a budding botanist, his journals make evident a sustained interest in the taxonomic class of Aves—our fine-feathered friends of the sky. Taken seriously, birding is an outdoor diversion of the very best sort, appealing about equally to the beauty-seeking soul and truth-hungry mind of anyone who engages in it. A great resource for beginning birders learning the ropes or lapsed veterans knocking off the rust is the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Corny Orny, as I call it, offers online classes, extensive databases, and cutting-edge digital apps that can greatly enrich your birding experience. So be like Pud and light out for the world, even if it’s only your backyard or the local park. Our economy isn’t the only thing that’s been hurt by the corona shutdown. It’s time for us to get back to the business of being human.  Effie Mae’s son Doug served on the USS Canopus, a U.S. Navy submarine tender, during the 1930s. Doug died in 1988, three years before my mother. Effie Mae’s son Doug served on the USS Canopus, a U.S. Navy submarine tender, during the 1930s. Doug died in 1988, three years before my mother. Yesterday I talked with Effie Mae’s granddaughter. Doug’s daughter. Many of you who have read Next Train Out know that the novel is based on the life of my grandfather, William Lyons Board. You know that most of the major events in the book are factual, according to historical records uncovered over years of research. But you may not have fully understood that Effie Mae, the other narrator in the novel, was also drawn nearly completely from records of her life. The same goes for Doug, her youngest son. Some years ago my friend and collaborator, Chuck Camp, found Kathleen, Effie Mae’s granddaughter, in the Washington, D. C. area. He talked to her a few times, pressed her about what she knew about her grandmother, who had died before she was born. The details were few, but Kathleen was able to relay some sense of the warm relationship her dad had with both his mother, Effie Mae, and his stepfather, “Bill” Board. Chuck and I had tried to arrange a trip to meet Kathleen and interview her in person, but we kept bumping into scheduling obstacles. Eventually, I shifted from a focus on research to writing the novel, and I threw all my energy into getting words down on the page. All along, of course, I knew Kathleen was out there, and I hoped to finally meet her. I had planned to invite her as a guest of honor to the book launch party that had been scheduled for April. When the coronavirus forced us to abandon those plans, I once again turned my attention to other things. So it wasn’t until yesterday that I picked up the phone and “dialed” the number I had for her, not knowing if it would still be valid. As I was leaving a message, she picked up. We had a delightful conversation, and I am now more eager than ever to visit her in person—whenever that is possible. I confirmed some things we have in common: she and I both grew up in Baltimore, and we both spent at least part of our careers as technical writers. (One distinction: she is still working and loves her job.) In a brief email I sent to her afterwards, I suggested that perhaps we are “step-grandsisters,” her grandmother having married my grandfather. I have mailed her a copy of the book, and I look forward to discussing it with her after she has read it. No doubt much of it will feel familiar to her. She may also learn some things about her grandmother’s life. And I’m certain she’ll learn a good bit about the man her grandmother married during the Great Depression. I’ve written before about how these writing projects I’ve undertaken over the last four years have led my life in unexpected directions. I’ve made significant new connections with people whose lives somehow intersected with members of my family. It has been genuinely remarkable. And I’m more and more grateful every day. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed