Pat and Nancy Denny (and me) at their sister Betsy's wedding in 1964. Pat and Nancy Denny (and me) at their sister Betsy's wedding in 1964. One of the best outcomes of publishing The Last Resort has been reconnecting with people who were vitally important to me at various stages of my life. I have exchanged lengthy emails with my dad’s former students, fascinating individuals who loomed large during my childhood. I have visited family members of my dad’s colleagues in far-flung states, including the Denny family who hosted us for my earliest remembered Thanksgivings. I have traveled to Atlanta with my cousins—who fished Salt River with their Uncle Pud—to visit the surviving members of the band of boys who frequented The Last Resort. And I have reached out to an old childhood playmate whose dad unwittingly stepped into the role my own father would have played, taking me to his “camp” on the Kentucky River. In fact, just when I thought the memory of my parents, who died 50 and 26 years ago, was nearly extinguished, I discovered numerous people, including some I had never met, who still remember their laugh or their intelligence and could share stories I had never heard. That has been remarkable. I have also made new connections I wish I hadn’t waited so long to forge, primarily with the children of my dad’s sidekick, Bobby Cole. Bob and Julie have provided insight into their family history and the land their family owned, where Bobby and Pud built the cabin. As children, they continued to spend time there, before I was even aware it had ever existed. They have first-hand knowledge of fishing Salt River and wandering along its banks. And, although our paths had never crossed until after their father died in 2013, we have discovered many unexpected points where our personal histories intersected. This is the real reason to undertake a project like this one. It’s satisfying to produce a book that honors your history and evokes unexpected emotions and memories in its readers. It’s uplifting to see a project come to fruition after a lot of hard work. But the most valuable outcome of the book is that putting it together pushed me to seek out people I love and cherish. If I have learned anything, I hope it is the importance of spending more time in their company.

0 Comments

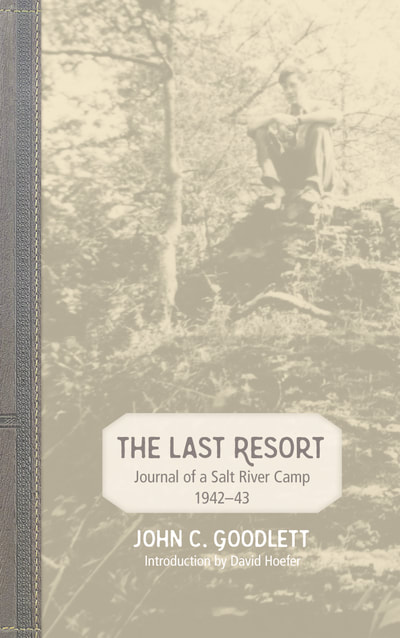

Tastefully Kentucky, on Main St. in Lawrenceburg, will stock The Last Resort. Tastefully Kentucky, on Main St. in Lawrenceburg, will stock The Last Resort. I am not an extrovert. I prefer running alone rather than with a run club, and sitting in my backyard with a book over joining a group of friends (whom I love dearly) for dinner. And I never mastered small-talk, although the many jobs I’ve had did finally force me to develop a basic level of competence in that area. So the solitary work of writing and editing and designing suits me fine. But now I have to focus my attention on marketing The Last Resort, which involves stepping outside my comfort zone and introducing myself to lots of strangers. Ouch. I’m learning, however, that it helps when the “product” sells itself. First of all, I am not even marketing my own words; I am marketing an amazing time capsule that my father authored 75 years ago. I’m more like an agent. It’s personal, but I’m not embarrassed by my own perceived lack of skill or talent. I know I can genuinely relate to the story in the book, and I’m certain others can, too. So on Monday my husband and I headed to Lawrenceburg, Ky., the site of The Last Resort, for our first marketing foray. The warm and generous folks there couldn’t have made it any easier for me. We made several stops along Main Street and at the gift shops of the nearby distilleries. We chatted with shopkeepers and others who just happened to be walking the sidewalks. Most were interested in the book because it’s an authentic local story. Many gasped with emotion when I pulled out the original journal, the 75-year-old family relic. That seemed to make what could have been a distant story feel very real. We had a fabulous lunch at one of the outstanding restaurants along Main Street. Then, as we headed back to our car, Eric Silverman at Tastefully Kentucky stuck his head out the door of the shop and let us know that they were placing an order for copies of The Last Resort for his customers. Citizens of Lawrenceburg: take note! If you are intrigued by the world you discover in The Last Resort, I encourage you to make a pilgrimage to Lawrenceburg and Anderson County. You can still see the fine old homes along South Main that Pud passed on his way home from the bus station, and the former Ripy Brothers (Wild Turkey) and Old Joe (Four Roses) distilleries now have first-class facilities where visitors can learn more about the bourbon industry. Drive through the tiny communities of Bonds Mill or Fox Creek to get a glimpse of Salt River—or drive across the river’s shale bed at Rice Crossing, the route Pud and his friends frequently took to get to The Last Resort. In many ways, Anderson County may be a very different place today than it was in 1942, but I promise you its easy-going charm has not disappeared.  My dad with, from left, my cousin Martha, me, and my sister Ginny. My dad with, from left, my cousin Martha, me, and my sister Ginny. I’m reading Regina Robertson’s excellent collection of essays detailing the stories of daughters who have lost their fathers, whether to death, divorce, or abandonment. The book, He Never Came Home, includes a foreword by Joy-Ann Reid, who writes: "[A]s the women who share their stories in this book reveal, how that loss shapes you depends less on the substance of the man who’s gone away or on his manner of leaving—whether through addiction and self-harm, or suicide, or apparent uninterest, or the unyielding, icy authority of mortal disease—and more on what the loss created in the mourner: in some cases, resilience; in others, self-doubt; in still others, a determination to move on and to be whole, regardless." I am a second-generation daughter who grew up without a father. As I relayed in the afterword to The Last Resort, my father, from all outward appearances a healthy man, died unexpectedly of a heart attack when I was 7, leaving behind my mother, my older sister, and me. Thinking back, I grew up among strong women: my mother and my aunts—my father’s sisters-in-law—in particular. Their husbands, my father’s brothers, were still around, but my father’s death, or perhaps a genetic inclination to depression, seemed to accelerate their natural withdrawal from the larger family. One generation back, my mother’s father abandoned his wife and newborn daughter in 1921 and simply disappeared. As far as we know, the family never heard from him again. My mother, though she rarely mentioned it, felt acutely her whole life the grief and anger that arose from a father who evidently didn’t care enough to stick around and never even bothered to find out what happened to her. I have to think that watching her two daughters grow up without a father, just as she had, compounded her pain. It wasn’t until the advent of the Internet, after my mother’s death, that we were able to drudge up simple public records that tracked his surprising odyssey around the country. But that’s fodder for my next book. As Ms. Reid’s words suggest, we all handle these absences differently. Certainly a number of factors affect our reactions, but I have come to believe that the age of the child at the time of the loss makes a critical difference. I suppose I can argue that I was young enough not to have been as attached to my father as my older sister was. He traveled a lot with his work and wasn’t around the house much. My sister identified more closely with him as a child, and I believe she suffered more than I did after he died. Not having a father around seemed to make me more determined to prove that I was the strong member of the family who could pick up the slack. Despite my tiny size, I mowed the yard. I trimmed the hedges. I shoveled the driveway. In fact, my mother was quite distressed when she was unable to convince the administrators at my high school that I should be able to take “shop,” as we called industrial arts back then. But girls weren’t allowed in that class. I think I was secretly relieved. I discovered later I have no spatial aptitude and no real interest in learning how to use tools. But I was the one who could soldier on. My mother quietly fell into a sort of depression that gave her permission to retreat into mysteries and bourbon each evening after she got through a day’s work. My sister lashed out in anger and bitterness at the world’s stupidity and injustices. I just plugged along, trying my best to do what I was supposed to do. We all deal with grief differently. But it takes its toll on all of us. Ms. Robertson’s book provides an intimate and sometimes painful insight into how daughters mourn their fathers. It’s a book I would recommend to every father and every man who wants to be a father. You can’t miss the key message: All you dads out there? You really, really matter.  Yesterday a friend of mine mentioned how unifying nature can be. She and her husband had recently been out west visiting some of our inimitable national parks. She relayed how, in a crowd of people of all nationalities, all colors, and all ages, everyone seemed to have the same reaction to a spectacular vista or a gamboling baby animal. As if according to some inaudible cue, each individual would simultaneously gasp or laugh or smile or turn excitedly and point out the scene to someone standing nearby. In the midst of omnipotent nature, we are all in awe. Our reactions are the same, whatever our religion, whatever our cultural experiences, whatever our political beliefs. It was a remarkable moment of clarity, she said. In an era where we sometimes feel irreparably divided, painfully separated from each other, the beauty and majesty of nature seemed to momentarily bring everyone together. Any tensions that may have existed among this disparate group of people in another setting seemed to dissolve when all were focused on the grandeur of nature. It seems too simple a solution, perhaps. If everyone spent more time immersed in the natural world, could we all be more tolerant of each other? More understanding of our differences? Better able to recognize the many ways we are all the same? There is no doubt time spent in nature has a healing power. It calms us. Brings us peace. Reconnects us to our most elemental selves. Perhaps my friend has stumbled upon one piece of the solution to our fractured society. While working on The Last Resort, I realized that my need to spend time outdoors is probably an inherited trait. I need to be soothed by a verdant woodland or a gurgling stream. Perhaps everyone does. I encourage you to put down your electronic device, step away from that keyboard, and take a few minutes to really notice something in your natural surroundings. Step outside for a moment and watch a bird circling a tree, feel the soft grass under your bare feet, listen to the chattering of a squirrel, check out what’s growing in your neighbor’s flower pot, look up at the clouds. Allow all your senses to really focus on something other than the strife in the world for just a few minutes. Don’t you feel better already?  As citizens across our nation continue to reel from the images of the recent tragic events in Charlottesville, Va., I am reminded of the value of first-hand accounts that document history in real-time. Any arguments that events generally accepted as historical fact did not occur are rather easily disputed when you are able to produce personal diaries, letters, or other notations written by people who witnessed them. Although personal accounts can be unreliable, a collection of similar eyewitness statements that present the same general assemblage of facts can construct a fairly robust understanding of what actually took place. If you have read Elie Wiesel’s Night, if you have visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., then you have been shaken to the core by first-hand accounts of the atrocities committed by the Nazis. The facts are so heinous that they are difficult to grasp. But you know that you must grapple with those facts because they are part of our history, and they are vitally important. We cannot ignore them, and we cannot forget them. With even a minimal understanding of that history, it feels impossible to stand by and watch young Americans speak the hateful words and imitate the gestures common among Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s. How have we failed to educate our youth about the consequences of the ideology they profess to embrace? The Last Resort is a first-hand account of young men in rural America in the mid-twentieth century making the most of the time they snatch away from other responsibilities. Their hideaway in the woods was indeed a world away from the scene unfolding across Europe. For a number of reasons, that idyll along Salt River had to come to an end. The first appendix in the book offers a first-hand account of what it was like for the author to transition from relatively care-free college student to soldier in Patton’s Third Army. And that American soldier, with his keenly developed observational skills, documented his personal encounter with the aftermath of the Final Solution. We know that we cannot remain silent. We have seen what happens when we do. I am grateful that I can share one more piece of evidence to support why.  I spent some time this afternoon thumbing through a printed proof of The Last Resort, and it’s hard to describe the sense of satisfaction that brings. I’ve nervously anticipated its arrival for two weeks, as we tweaked the final formatting for the publishing process. Now I have tangible proof of all of our labor over the past two-and-a-half years, and I am overjoyed. I began working on The Last Resort in earnest in early 2015 after leaving full-time employment. The first task was simply typing the handwritten journal. Even that had its challenges, I learned. Reading my father’s handwriting, in pencil, after more than 70 years was difficult at times, especially for someone (like me) whose vision is badly compromised. Then there was the issue of all the taxonomic identifiers in the text—all those genus and species names that I was not familiar with. I tried to verify every one as I typed. That really slowed me down. Once that step was behind me, my collaborator, David Hoefer, urged me to annotate every reference that might be unfamiliar to today’s readers. That included people, places, colloquial expressions, historical references, etc. That phase required contacting a lot of Anderson County natives and spending time at the current site of Camp Last Resort. David did a massive amount of research into disparate topics like old fishing lures, World War II-era firearms and airplanes, and the geography of the area. Then I turned to reading through other materials my father had left behind, including some correspondence from World War II and the second journal from the 1950s. Those also had to be transcribed and annotated. Eventually, we wrapped up the difficult process of choosing excerpts to include in the final book. After a nine-month interruption, during which David and I both dug into other projects, we picked back up with fiery determination in May, with the goal of publishing by the end of the summer. These last few months have been an intense period of proofreading, verifying facts, designing the layout, selecting photos, and polishing the final product. I am proud of the book we have produced, and I can’t wait to make it available to you. Stay tuned for news of publication dates and launch parties! A good designer sometimes proves how misguided you are. Oh, not in a blustery, arrogant way, but in a quiet, effective way. And I was lucky enough, when it finally was time to have a cover designed for The Last Resort, to hook up with one of the best. For two years I thought I knew exactly how I wanted the cover to look. I had a photo in mind that would be perfect. It would relay both the passage of time integral to the story as well as the eternal hope and beauty inherent in the natural world. But I was wrong. Oh so wrong. Nonetheless, I confidently relayed my ideas to Barbara Grinnell, designer extraordinaire. She listened closely. She faithfully rendered the very idea I had in mind. And then she created the perfect cover for the book. She presented them both to me simultaneously. When she did, she wisely numbered the one I had asked for “1,” so I looked at it first. I loved it. It was everything I wanted. Then I looked at her second offering. And I was blown away. It was so simple, but it was exactly right. I had convinced myself that the cover had to be bright and colorful for the book to be noticed. But it’s a quiet little book about an era long ago. It’s filled with black-and-white photos from the 1940s. I immediately understood that it needed a cover that evoked those qualities, not a braggartly, ostentatious cover that would attract readers looking for something other than what was inside.

I shared the cover options with a small focus group of friends, relatives, and strangers. Everyone agreed that the choice was clear. The cover of The Last Resort is authentic to the material inside. And I have Barbara Grinnell to thank for leading me in the right direction. By creating both the cover I wanted and the cover I needed, she made me see how wrong my initial instincts were. If you have a design project you think Barbara could help you with, I hope you’ll get in touch with her at [email protected]. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed