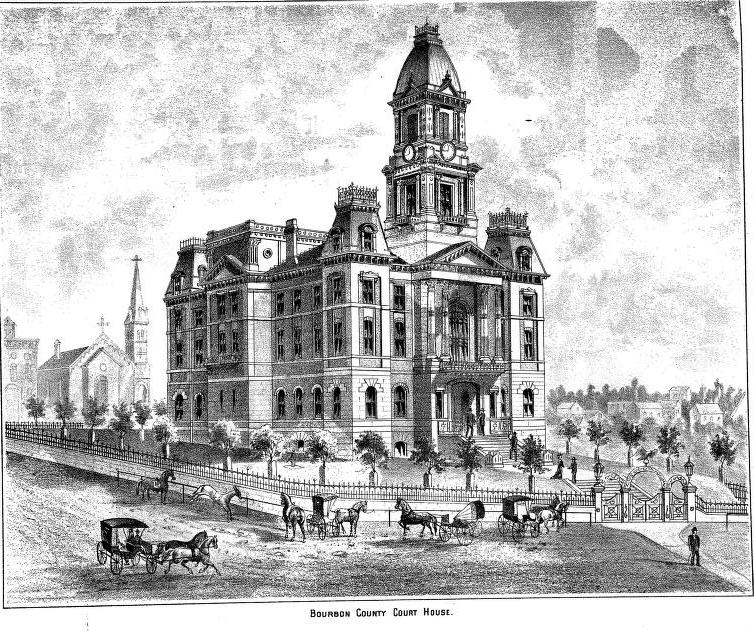

The Bourbon County Courthouse, which was destroyed by fire on October 19, 1901, just eight months after the arched gate at the bottom right was used to lynch George Carter. The citizens of Paris preserved the iron gate after the fire and it still stands adjacent to a historic building in downtown Paris. As I’ve worked on my novel over the past three years, I’ve dedicated large chunks of time to researching or writing about the first half of the 20th century. I’ve tried to grasp the cultural and societal impact of two World Wars, the Great Depression, the rise of labor unions, and expanded access to telephones and automobiles. I’ve thought about how different parts of the country—from Miami to Toledo to the coal towns of Eastern Kentucky—responded to those changes.

That’s a tall order, and I’m certain I’ve barely scratched the surface of all I need to know. Nonetheless, I’ve frequently found myself immersed in another place and time—worlds that one would think are quite different from our 21st-century reality. So I was somewhat surprised when I opened the Sunday Herald-Leader on November 24 and discovered two articles on the opinion page addressing a theme that runs through my novel. In one, Western Kentucky native LaTonia Jones writes about her youth in Paducah, where she played innocently in the cool grass on the very site where two black men, Brack Kinley and Luther Durrett, were lynched on October 13, 1916. In the other, University of Kentucky Ph.D. candidate Carson Benn recognizes the 100th anniversary of the efforts of the citizens of Corbin, Ky., on October 30, 1919, to expel all the black residents from their town. Unfortunately, the term “lynching,” and all the ugly and unforgivable history it represents, has recently been a part of our national conversation. And it was only a few short months ago that we were talking about sending certain people in our country back where they came from. It appears that in the 100+ years that have intervened since the events memorialized in these articles we have progressed very little. That we would resurrect these expressions and use them for personal advancement is unthinkable. That we still shy away from the conversations necessary to address simmering resentments is inexcusable. Can we ever find a way to embrace all our fellow citizens equally and justly? My grandfather, whose life is fictionalized in Next Train Out, worked at a pharmacy in Corbin in 1914. In a scene in the novel, he returns to Corbin in 1934 and reflects on this shameful event in the town’s history, an event he views through the lens of a World War I veteran who trained alongside black recruits. At this point, he has also spent a lifetime coming to grips with the perverted justice he witnessed as an eight-year-old boy in Paris, Ky.—the same sort of justice that LaTonia Jones’ ancestors witnessed. Evidently we still have much to learn from our history. Almost despite ourselves, we continue to find ways to inflict harm on each other, wittingly or unwittingly. And that is why it is so important that Ms. Jones and Mr. Benn and others continue to remind us of our past. Burying it will only let the cancer grow. Bringing it into the light, as is the goal of the Sunup Initiative in Corbin, is how we may best be able to change course.

2 Comments

The forlornness of an empty boat dock. Photo by Rick Showalter. The forlornness of an empty boat dock. Photo by Rick Showalter. After the longest summer in memory, we’re finally transitioning to winter. A little snow this week offered a taste of my favorite weather: bright blue skies, snow balancing on the tree limbs, and temperatures in the 20s keeping the ground hard and the mud at bay. One sign of impending colder weather at my house is the dry-docking of our metal johnboat. In our case, this simply means hauling the boat out of the water and leaving it to rest upside-down on the nearby shore. I came back from an event last Sunday afternoon and saw the boat was missing from its slip. That always makes me a little sad. Although we rarely take the boat for a spin on the lake these days—lightweight kayaks are just so much easier—its mere presence suggests the possibility of a lazy summer day fishing on the lake. It evokes nostalgia for a more tranquil time when bobbing on the water was an acceptable way to spend an afternoon. But we have found that ice tends to build up inside the boat in the winter, and harsh winds can then heave the extra weight against the aging dock and pull hard at our makeshift mooring. Removing it from the water this time of year eliminates one thing we have to worry about. When it’s missing, however, I feel the void, the absence of something significant. I’m in the middle of another transition that could also symbolize a sort of loss, if I allowed it to. But I prefer to see it as an empowerment, a taking control of a situation that could at times feel hopeless, a situation that made me grapple with my own worth and the value of the work I’ve chosen to do. This is familiar territory for every writer who wants to see work published. I’ve spent several months reaching out to literary agents and small publishing houses searching for someone who might be willing to take a chance on my novel. Like so many writers, I now have only an inbox full of rejections to show for my efforts. It’s a tedious, time-consuming process that I still find interesting, but I’ve decided it’s just not how I want to wile away my hours. I’m ready to accept defeat and retake control of my project. It takes a certain self-assuredness—or even cockiness—that I don’t normally possess to assume that my book has value even though no legitimate enterprise agrees. What’s at stake, however, is small: personal embarrassment, acknowledgment that my talent and skills are limited, shunning by those with legitimate claim to the title “writer.” I can accept that. I have no other literary aspirations. I’m ready to take the chance. So I’m getting excited about designing the book that I want to offer to willing readers. I’ll be able to title it what I want, include the front matter I want, and rely on my talented graphic designer, Barbara Grinnell, to create a cover we both love. Of course, the final editing and proofing will now fall on me, or on other professionals I enlist to help. But I think I have a course mapped out, and I’m excited to be going down this road. It’s freeing sometimes to let go of dreams that are only weighing us down. Sometimes we have to turn a corner, move in another direction, accept a transition to an imperfect state of things. I’ve written a story that I want to share with friends and family who are interested, and I have a path for accomplishing that. That’s what’s important. And that I can do. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed