Cooper the Imperious. Photo by Bob Cox. Cooper the Imperious. Photo by Bob Cox. Bob Cox, of Frankfort, Ky., shares the joy of loving dogs. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. I’m awake at 4 a.m. I am most certainly a dog lover. Otherwise I would be frustrated, angry, or stubbornly still asleep. I am sitting on my back porch with my dog, Cooper, as he guards our yard. It has become a far too familiar routine for Cooper to demand to go out in the middle of the night so he can stand sentry at the corner of our patio, protecting our home from all sorts of danger: squirrels, rabbits, birds. He snaps a single bark every 30 seconds or so just to remind the predators that he is at his post and there will be hell to pay for any enemy that dares to approach. How did I get here? My life is under the control of this dog and his whims. Worse yet, it thoroughly pleases me. Am I deranged? No, I am a dog lover. This madness started 60 years ago with my first dog, Pretzel. Next came Khaki and then Q-tip. There has always been a dog in my life. Or should I say ruling my life? So when Cooper awakened me in the middle of the night, demanding to go outside, I of course let him out. This morning I decided to sit next to Cooper to dissuade him from barking too much and waking my wife who must be up in a couple of hours for work. I thought I would make good use of the moment and jot down a few thoughts. It’s unlikely that I will be able to go back to sleep. And since this all is related to Cooper’s happiness (sigh), I’m good with it. Cooper’s obedience training, or rather lack thereof, is a mirror of my own personality: I, too, like to break a rule now and then. A well-trained dog would not be allowed to disrupt the household for a midnight lark that is obviously not necessary. But I have taught Cooper, who sleeps next to me (OK, that’s a whole other indulgence) that if he nudges me enough, I will let him out. For the record, this only happens a couple of times a week. Usually it’s a 10-minute interruption and we both go back to sleep. But who am I kidding? It’s totally up to Cooper, and he knows it. Pretzel was my first dog. He joined our family when I was two years old. He was a full-size dachshund. We lived in a suburban neighborhood in a small town in the 1960s. In those days, children were outside and free to play without supervision. Pretzel was always at my side as I played with my matchbox cars in the sandbox and later roamed about on my bicycle. I remember that I loved to splash through mud puddles, and Pretzel loved to jump in with me. We often came home filthy and were thrown into the tub together. Certainly, a bond was formed between boy and dog. When I started my own family, I wanted my children to have a dog experience. We got Khaki, a golden retriever. Khaki lived in a household with four rambunctious boys. I made a decent effort training Khaki and he was a wonderful family pet. Khaki was allowed to explore freely and he became friends with everyone in the neighborhood. Occasionally, Khaki brought us an unexpected gift, such as my neighbor’s golf shoe. He was a mascot at all the kids’ ballgames and a regular fixture on vacations. Each of my sons remembers Khaki and, now, each of their families has at least one dog. One son has two dogs. One son has three. My wife did not grow up with the same affection (affliction?) for dogs. She tolerated them. When Q-tip, a rescue mix came home, my wife was not at all thrilled. Q-tip, named for the little white tuffs only on his toes, was a bit mischievous. He shed and left parts of himself everywhere. His chewing stage lasted longer than most, and we still have corners of furniture nicely carved by his artful work. We nicknamed him Houdini for his many escapes from our fenced-in yard. He repeatedly made a beeline for the Pet Resort down the street and found a way to join the dogs inside the play area. The owner kept my phone number handy to let me know that Q-tip had once again checked himself into the resort and I could pick him up when I was ready. Q-tip became my running companion. He learned to follow me off lead and we put in many miles together. Once he detoured inside a neighbor’s house that was open for spring cleaning and then rejoined the route. I still miss that special companionship.  That brings me back to Cooper. Cooper is a Shorkie; a Shih Tzu/Yorkshire designer dog. In other words, a high-priced mutt. In my retirement, Cooper is with me for the largest part of every day. Together we walk an average of five miles, which is great for us both. Cooper loves car rides and must have his head out the window in the wind. I enjoy taking him with me to dog-friendly restaurants and stores. We are regular patrons at the wine bar in downtown Frankfort: Cooper has a bowl of water while I sip a Cabernet on the patio. We just spent a day at Red River Gorge where he scampered along the trail and romped through the streams. Cooper, I am happy to say, has also won over my wife. We are so enthralled with him that we have complete conversations telling each other what Cooper thinks or wants. In fact we have playfully discussed custody of Cooper in the event of an unlikely marriage separation. It’s now time for my wife to get up. Cooper is pawing at my arm telling me he’s ready for his morning walk. I will close my laptop and happily take him. That’s what I always do. It’s ingrained in me. I am a dog lover. “Once you have had a wonderful dog, a life without one is a life diminished.”

–Dean Koontz

5 Comments

Twelve dogs. Thirty-two people. Utter chaos. But what would you expect at a “Sweet 16” party for the neighborhood’s aged, treat-demanding road warrior, known to all for her staggering determination as she winds her way from one friend’s house to the next, stubbornly dragging her recalcitrant back legs…and her impatient, frequently annoyed human? Yes, indeedy, last weekend Lucy was queen for a day. Somehow she seemed to know that all her friends had gathered in our cul-de-sac to honor her amazing longevity. At a muscle-bound 70 pounds, few would have predicted a dog her size would live so long. Was it the daily walks that started as soon as she arrived at our home at nine months? The vet-recommended dog food? The crazy mix of breeds her recent DNA test revealed (American Bulldog, Doberman Pinscher, Llewellin Setter, German Shepherd, Norwegian Elkhound, Chow, Boxer, and Lhasa Apso)? Or, more likely, was it her newfound joy in socializing that has given her that extra oomph to keep going…and going and going? As a youngster, Lucy eagerly approached people, but she didn’t want you to touch her. If you tried to pat her, she would pull her head away like a negative pole repelled by another negative pole. We called her “the don’t touch me dog.” And she seemed determined to assert her dominance over other female dogs, which didn’t gain her many friends. Only a few large, brave males—like her best friend Ziggy—knew how to handle her. And those two ran lightening loops around Ziggy’s house, threatening any human knees that got in their way. But now, in her doddering years, she has softened (some), and she seems motivated to visit with all her human and doggie friends up and down the hilly neighborhood streets. It’s quite the spectacle. I fully expect someone to call the SPCA on us for mistreating an old dog. But she sets the course—and its length. She is still strong enough and oh so stubborn enough to dictate where she goes and when. Photos courtesy of Lynne Craft and Rick Showalter. Much has been written lately about our epidemic of loneliness. The U.S. Surgeon General recently called it a “major public health concern.” The pandemic and its isolation, of course, broadened and deepened the problem. Our addiction to our handheld devices has also contributed. It’s just too easy to bury ourselves in a digital world and ignore the wider community. We used to be more gregarious, perhaps by necessity. We didn’t have easy entertainment at our fingertips. One of Lucy’s favorite people (she has treats and two big, beautiful dogs) recently commented how we rarely sit on our front porches or in our yards and visit with passing neighbors. That habit has been dwindling for a couple of generations, of course. But during the pandemic, she and her husband did exactly that. They set up lawn chairs in front of their home and allowed their yard to become an ad-hoc playground for all the neighborhood dogs. As their owners walked by, they couldn’t help but be lured by the frolicking dogs and the friendly chatter and tarry for a moment. Research has indicated that owning a dog can improve your health, in part because a dog encourages both physical activity and social interactions. As Lucy drags me out for yet another two-mile two-hour amble, I think I’m doing it to keep her joints supple. She thinks there might be treats in it for her. In reality, we’re two crotchety old women pushing each other to expand our worlds. We’re inadvertently building a “culture of connection.” And that’s what led to the lively scene on our street on a windy Sunday afternoon in late April, as a host of joyous friends and neighbors—two-legged and four-legged—celebrated Lucy’s special day. As the Surgeon General pointed out, “Social connection reduces the risk of premature mortality.” With so many pulling for her, Lucy might just live forever. Happy birthday video!Click here to watch Lucy react to her friends singing happy birthday to her. Video courtesy of Lynne Craft.

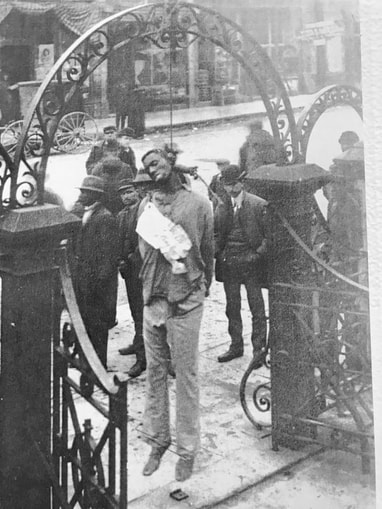

George Carter and the crowd he attracted after his hanging in February 1901. George Carter and the crowd he attracted after his hanging in February 1901. I have been haunted by the case of Ralph Jarl, the Black 16-year-old in Missouri who was shot by Andrew Lester after ringing the elderly white man’s doorbell. Jarl’s mother had asked him to pick up his two younger brothers at a nearby home, but Jarl had mistakenly approached a home on the wrong street. Everything about this situation is shocking. Lester’s behavior is reprehensible and inexcusable, no matter how broadly you interpret Missouri’s Stand Your Ground law. Jarl did nothing more threatening than ring the man’s doorbell. In my youth, someone like Lester might have yelled, “Scram, you punk!” (Well, he might have used a different epithet.) Lester also could have opted to ignore the doorbell and simply not answer the door. But Lester made the choice to shoot the teenager—twice—without exchanging any words. In the criminal complaint, Lester stated that he was “‘scared to death’ due to the male’s size.” This is the detail that caught my attention. Jarl’s family has reported that the youngster is 5’8” and weighs 140 pounds. Lester claimed Jarl was 6 feet tall. There is a considerable discrepancy here between reality and Lester’s perception. I have seen this before. In Tessa Bishop Hoggard’s book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter, Hoggard relays the story of my great-grandmother’s alleged assault by a Black man while crossing a covered bridge in Paris, Ky., in December 1900. The initial report in the Kentuckian-Citizen newspaper described the incident as an attempted purse snatching. In my great-grandmother’s words, her attacker “had brown skin, weight about 200 pounds, fairly well dressed….” Two months later, a suspect was pulled from his jail cell by a group of local men and lynched in front of the county courthouse. The victim of this extrajudicial justice, George Carter, had never been charged with my great-grandmother’s assault. He was being held in the jail for another offense. But rumors had led to suspicions that he was the guilty man, and the crime against my great-grandmother had also morphed in the prurient imaginations of concerned citizens. But, as you can see from the photo, George Carter clearly was not 200 pounds. In their rush to defend my great-grandmother’s honor, did the mob hang a man who had nothing to do with the incident on the bridge? Or was the description my great-grandmother gave the newspaper at the time of the attack yet another example of white victims reporting Black perpetrators as much larger and more physically threatening than they actually are? In her book, Hoggard also relays the story of another mob lynching in Paris in 1889, where the victim had again been described by the woman he allegedly attacked as “a large, burly Negro, weighing over 200 pounds.” We have no photograph of Jim Kelly to confirm his physical size, but the common language feels suspicious, like a trope that was cemented in the minds of a fearful white population. According to the Washington Post: “In multiple studies, people who were asked to judge the size of Black people tended to see Black men as bigger and stronger than they actually were, and gave Black children the attributes of adults. The result is that they are seen as more dangerous....In some studies, [Kurt Hugenberg, a professor in psychological and brain sciences at Indiana University] showed participants images of Black men and White men who are about the same height and weight. Participants often thought the Black men appeared larger...” Yes, Virginia, there is systemic racism. It permeates so many aspects of our lives and our interactions that even those of us who try valiantly to reject racist tropes inevitably fall under their sway. Racism is pernicious, it’s prevalent, and it’s dangerous. If we refuse to recognize that, we can’t even begin to chip away at the corrosion it has caused. And our fellow citizens will continue to pay the price. “Living with regrets is like driving a car that only moves in reverse.” — Jodi Picoult  Cooper visits Kentucky’s capitol. Photo by Bob Cox. Cooper visits Kentucky’s capitol. Photo by Bob Cox. Bob Cox, of Frankfort, Ky., shares more about the good life. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. Today I got up at sunrise and walked my dog, Cooper, early enough that I could spy on the neighbors as they scrambled for work. The weather was agreeable, so I took my coffee outside. I had one goal for the day: mow the lawn and refurbish the mulch. I knocked that out before lunch. Then I walked the dog again. I spent a couple of hours on an oil painting that I am preparing to give to a friend. Then, suddenly, I had the desire to write this essay. Later, there might be a glass of wine on the deck before I finish the final draft. I will then enjoy the evening chatting with my wife about her work day and our upcoming plans for a week in Florida. I most likely will be in bed early, reading. Earlier this week, I took a five-mile hike at Red River Gorge; painted the upstairs bathroom; babysat my 18-month-old grandson; attended both granddaughters’ soccer games; and took my mom out for lunch. Yes, I am retired. I’ve written about this before. But I have been at it a year now, and I wanted to report that it has been even better than I expected. So many people I know seem reticent to take the plunge, even when they have a retirement plan in place and can check all the boxes. So I wanted to share my exuberance about what retirement offers. Retirement is like no other stage of life, for two rather obvious reasons. First, you are free to choose what happens every single day. Second, you can invest time in the things that truly matter to you. That’s it. That’s the secret that I had failed to recognize before I spent my last day at work. Typically, I do not like routine. For most of my life it annoyed me to follow a schedule. Now, however, in order to fit in all the things I want to do, I find myself loosely planning about a week ahead. I still get up when I feel like it, do what makes me happy, and feel NO guilt about my choices. When I retired, I did make one commitment to myself: I wanted to see results. I intended to invest all my resources, both emotional and financial, in a life that would bring me peace. I wanted to spend more time with friends and family. I wanted to travel—long trips and short, expensive and not so much. Clearly, I recognize how fortunate I am. Not everyone has the choices I do. My health is good. My wife is still employed and gave me her blessing to retire. We have the financial resources to enjoy this time. My mother is nearly 89, and I am free to take her to lunch or for a drive in the country, listening to her stories. I can build memories with my grandchildren, as I recall all the things I learned from my own grandparents—especially my Granddad, whose wisdom is golden to me now.  Hiking with old friends. Photo by Bob Cox. Hiking with old friends. Photo by Bob Cox. Some fear they will become lonely and isolated when they retire, once they walk away from the social network they have built up during years of work. My circle of friends has actually expanded in retirement. I have close friends I regularly join for drinks or dinner. I spend time at the lake boating with my cousin. I play golf with a good buddy. I hike monthly with a group of retired high school mates. My wife and I recently visited friends at their winter beach house. I can choose to spend more time with more people. They all fit in my new schedule. So, here’s my unsolicited advice. Retire as soon as you can. There are hidden pleasures awaiting you. Each day you will have the freedom to choose what you want to do, and choose those things that matter most to you. “You are never too old to set another goal or to dream a new dream.” –Les Brown

Photo by Lucas Ludwig on Unsplash. Photo by Lucas Ludwig on Unsplash. Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., was inspired by Cathy Eads’ Drag-on to recount more reasons why we must not hide under a bushel. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. I knew if I just waited a week or so to respond I would have more fodder, because there is no limit to the pettiness, ignorance, and cruelty of most Republican officials, who hate America and God’s creation so deeply and with such passion. Let’s start with a first graders’ spring concert in Wisconsin. What could be cuter, right? Here’s something cuter: first graders singing “Rainbowland” (by Dolly and her goddaughter Miley) about a utopian world that could be possible if people lived in harmony. It almost makes me tear up just thinking about first graders singing “Chase dreams forever/I know there’s gonna be a greener land/ We are rainbows, me and you/Every color every hue.” But put that hanky away: administrators decided to ban the song, as it is perceived as “controversial” and might not be “appropriate for the age and maturity level of the students.” WTF? What could possibly be MORE appropriate for first graders? A re-enactment of Sandy Hook? The maturity level of the children is not the issue, but rather the maturity level of the adults. I’ll add that “Rainbow Connection” (by Kermit the frog) was apparently also banned from the first graders’ spring concert, but was reinstated, no doubt because the administrators feared they would be ridiculed for the buffoons they are. Really? Rainbows are the issue? Perhaps we should be reminded that rainbows are a sign of the “everlasting covenant between God and all living creatures of every kind on the earth” (Genesis 9:11–15). Moving on, but not really. I roughly quote below from an article by Charles Blow of the New York Times (emphasis mine): An elementary school in St. Petersburg, Florida, stopped showing a 1998 Disney movie about Ruby Bridges, the 6-year-old Black girl who integrated a public elementary school in New Orleans in 1960, because of a complaint lodged by a single parent who said she feared the film might teach children that white people hate Black people. (What? White people hate Black people?) Ruby, a first grader, had to endure throngs of white racists – adults! – jeering, hurling epithets, spitting at her, and threatening her life. But now a Florida parent worries that it’s too much for second graders to hear, see, and learn about in a considerably toned-down Disney movie. But of course, the point is not the protection of children but the deceiving of them. And the real point is that a single parent can object to a lesson or book and potentially have it banned. They are foot soldiers in the culture wars. A Toni Morrison book was banned for a rape scene. The Bible has rape scenes. Are we going to ban that? And moving not very far at all, a principal in Florida (of course) this month was pressured to resign after sixth-graders in his school were shown Michelangelo’s statue of David, a biblical figure no less, and three parents complained. Meanwhile, take no comfort in the promised administrators’ “review process” of these parental complaints, such has been enshrined in law here in Kentucky. There will be no funding for resources to review the hundreds of objections.

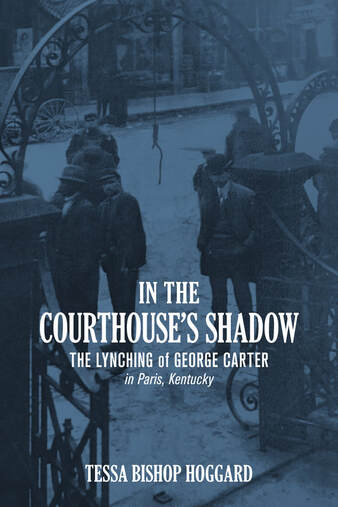

So while one individual can squash a book or lesson on the front lines, Republican legislators are establishing an infrastructure to dismantle the American system of government. In Wisconsin, hot on the heels of a win by a liberal-leaning judge who will take a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court, a new two-thirds Republican majority in the state’s Assembly is talking about its ability to remove that judge—or the governor or anyone else not to their liking. They likely won’t succeed, but it is the attitude, drunk with power, that is scary. In the wake of the success of abortion protections on ballots across the country, states are rewriting the rules to prevent mere citizens from placing such measures on the ballot. Conservative state houses are stripping Democratic governors of their powers. And duly elected state legislators are being expelled from their offices. In Tennessee this week, three legislators stood in front of the chamber and joined the chants of citizens in the gallery who were protesting the Republicans’ inaction after the recent slaughter of three nine-year-old students and three of their school’s staff members—in the very city where the state house stands—by a former student wielding three guns. For this transgression against decorum, the Tennessee House expelled the two young Black legislators—but NOT the white legislator who also joined the protest. That’s right: The Republican legislators took immediate punitive action toward those peaceably protesting the slaughter of innocents but did nothing about gun violence. Oh wait—they did do something: After the murders, members of the legislature who brought up the topic of gun violence…had their microphones shut off! Hence the protesting legislators’ need for a bullhorn to duly represent the will of their constituents. With the two expulsions, 140,000 citizens of Tennessee lost their representation in the Tennessee House. Did I already say that “Republican legislators are establishing an infrastructure to dismantle the American system of government?” You can’t make this stuff up. Wait another week and we’ll have more examples. The destruction of a free America is upon us. Our new national religion—hate—is here. Write (lots of) letters to the editor. Show up at a Trans rally. Speak the truth, loudly. It is a frustrating time. Many have pointed out that assault weapon owners, hypersensitive and maliciously aggressive school critics, historical revisionists, and election deniers and their ilk are in the minority. But they are loud and well-organized, and they vote. In 2019, for the first time ever, I volunteered to go door-to-door encouraging people to vote for Democratic Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear. (He won because of me!) The lesson we should take from this is that we, too, have to be loud, have to participate, and have to vote. Hang on to hope. Keep an eye on that rainbow.  Cathy Eads, of Atlanta, asks some charmingly obvious questions. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. Dragons pepper the stories of literature with the flavor of excitement, adventure, and terror. They provide a threatening menace for St. George to slay, prey for the chivalrous knights to hunt, and a dramatic theme in many a tale across ancient and modern times. Despite the detailed physical descriptions of their fiery breath and reptilian bodies, dragons are fictitious creations of our collective imagination. Most of us enjoy suspending our disbelief to indulge in the fun of reading about and watching the illusions of these mythical creatures. Make believe and pretend play are innocent and universally human endeavors. Remember who you pretended to be as a kid? A superhero? A cop or robber? A ghoul or villain? An astronaut or a star athlete? A character from your favorite book or movie? A princess, or maybe even a queen? Did you ever dress up and enjoy the fun of acting the part of your alter ego—especially if it showed off the polar opposite of your “normal” self? Ever feel a little extra confidence temporarily just because you were emboldened by playing the part? On Halloween, did dressing up make the candy haul a somewhat secondary reward to the compliments you earned for your awesome costume? Was anyone harmed by your dress-up acting? Did it threaten anyone’s identity? Did anyone suddenly change their mind about who they were on “regular days” because they witnessed you in costume? Did your pretending bring anyone joy? Did it make anyone laugh or smile, give a thumbs up or a high five? Did it entertain others? Did your pretending to be a fictitious character change who you were deep down inside—or open you up to feel more fully yourself, allowing your creativity to shine? Did it make you feel happy? Whenever a powerful group of people tries to extinguish an expression of other people’s freedom, joy, creativity, or shared happiness, THAT is no fictitious beast. THAT is a terrifyingly real and legitimately dangerous creation of human ignorance. To everyone who believes pretend, dress up, and make believe are one part of the human pursuit of happiness, I say DRAG-on, my friends, DRAG-ON! I wholeheartedly defend your right to do so and delight in the glittering sparks of joy it brings to this troubled world.  Tessa Bishop Hoggard with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of a lynching victim, George Carter. Tessa Bishop Hoggard with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of a lynching victim, George Carter. She spent years researching his family. She wrote and published a book examining the tragic story of his great-uncle. She arranged for him to meet a descendant of the woman who brought enormous grief upon his family. But she had never met him in person…until this week. Tessa Bishop Hoggard is on a mission. She recently traveled from her current home in Texas to her hometown of Paris, Ky., to round up support for her latest project: erecting a historical marker near the Paris courthouse where two Black men were lynched, in 1866 and 1901. The proposed marker will also honor a third man who was lynched nearby in 1889. Tessa’s purpose is clear: She wants to ensure that the citizens of her hometown—the old and the young—have the opportunity to confront the truths of its past. She is certain that only through acknowledging our dark history can we heal as a community and as a nation. So far her trip has been a success. After sending numerous emails and letters to local citizens and officials over the last year, she is finding that a brief face-to-face encounter seems to seal the deal. “I came prepared to recite the history of each of the three lynchings, to introduce these officials to the specific story of each individual,” Tessa told me. “But that hasn’t been necessary. As soon as they learn what I am proposing, they are offering support. I am truly flabbergasted. And elated.”  One of those victims of mob violence was Jim Bannister’s great-uncle, George Carter, who was hung on the iron gate in front of the courthouse in 1901. Carter was the older brother of Jim’s grandmother Katie—the woman who raised him. Two photos of Carter’s body hanging from the noose still exist and are reprinted in Tessa’s superb book In the Courthouse’s Shadow: The Lynching of George Carter in Paris, Kentucky. Those photos, and the newspaper description of the original incident that eventually led to mob violence, raise suspicions about whether Carter was even involved in the alleged “assault” of a local banker’s wife, Mary Lake Barnes Board, my great-grandmother. Initial reporting described the incident as an attack by “a negro man, who attempted to grab her pocket-book.” [The Kentuckian-Citizen, Paris, Ky., December 5, 1900] Many of you already know the story of how Tessa arranged from afar for me to have a public conversation with Jim Bannister in 2020. That conversation offered him an opportunity to express his grief and his frustration at not being able to uncover the truth of his great-uncle’s story, as well as his relief that it was finally being aired in public. It offered me a chance to publicly voice my regret for the horror his family endured and my apology for the role my family played in what took place. This week Tessa, Jim, and I gathered together for the first time. Emotions ran high. We took turns expressing how profoundly grateful we are for all that has transpired in the last two years. We hugged. I shed a few tears. Jim and I talk fairly often (we have to dissect Kentucky basketball on a regular basis), and I have seen him a handful of times, despite the challenges of the pandemic. But he and Tessa were in the same room for the first time. It was breathtaking to witness. In early 2023, Tessa will submit her application to the Historical Marker Program of the Kentucky Historical Society. It appears her trip this week has accomplished her goals: she has met with local officials, she has solicited letters of support, and she has revisited the scene of these tragic extrajudicial hangings. She also met George Carter’s great-nephew for the first time.  Sallie Showalter, the great-granddaughter of the woman allegedly assaulted by George Carter, with his great-nephew, Jim Bannister. Jim is holding his school photo from 1947-48, which Tessa found in her late mother’s belongings. Tessa’s interest in George Carter’s story was ignited when her mother shared a newspaper clipping she had kept from 1978 retelling the story of the hanging.  Yard signs in Louisville, Ky., October 31, 2022. Photo by Joe Ford. Yard signs in Louisville, Ky., October 31, 2022. Photo by Joe Ford. Joe Ford, of Louisville, Ky., offers some suggestions for the upcoming election. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. If you live in Kentucky, it’s time for our second spring—time to let your lawn sprout political signs! If you’re unsure about what varieties to cultivate, here are a couple of ideas: U.S. SenatorCharles Booker is a native Kentucky species, supportive of diversity and other species in our yards, well-adapted to our growing zone, enhancing the soil to support healthy growth of all plants, and displaying something of interest in all seasons. Rand Paul is an invasive species destructive to our lawns and crowding out our wide variety of native plants, which have little natural resistance to his bullying tactics that spread out-of-control suckers all over the property, threatening indigenous vegetation. Choice: Charles Booker. Amendment 2Yes is a noxious and poisonous cultivar, aggressive and mean. It is a variety bred by dogmatic politicians (mostly male) in Frankfort and Washington whose goal is to dominate smaller, weaker plants and weed out any that don’t reproduce exactly as they think they should. No recognizes the place each plant has in a diverse environment and its need for support and care during all seasons. With the help of a concerned gardener, each plant will thrive in its own space, in its own time. Choice: No Those are the two hot topics around here. Perhaps you have an opinion on your local plantings.

But seriously, put some signs out. Especially for those living out in the state, a sign or two may allow others to think, “Gee, someone else supports the positions I do. I am not awash in a sea of hopelessness and small thinking.” Do vote.  Artist: Bob Cox. Oil on canvas. Inspired by the Puffins on the Scottish Inner Hebrides. Artist: Bob Cox. Oil on canvas. Inspired by the Puffins on the Scottish Inner Hebrides. Bob Cox, of Frankfort, Ky., offers some insights into the joys of retirement. If you would like to submit a post to Clearing the Fog, please contact us here. Today I painted a puffin. I could not have done that last year. On a Monday morning a year ago I would have been jumping on a loan production call sweating that my boss would not be pleased with my meager efforts to grow the corporation. But now I am free. Every day offers a brand new adventure. I recently arrived at one of life’s great milestones. I had looked forward to the day with great anticipation. I set up a countdown calendar on my phone. I organized all of the important details I could imagine. I even planned a special toast with my wife at The Champagnery in Louisville. When December 31st arrived and it was official, I finally retired after working for 40 years. Now, I am several months into my newfound retirement. Newfound is an accurate description as this period in life has become a journey of discovery. I fully expected the jubilation that accompanies closing out one’s career. But I was unprepared and pleasantly surprised by the exuberance I now feel from the total freedom to decide what each day will hold. I am often asked, “Are you enjoying retirement?” That’s like asking a child if they are happy on Christmas Day. What is there not to like? My childhood friend and fellow retiree Sallie Showalter shared with me a perspective that a friend of hers had expressed: Our lives can be divided into thirds. The first third is preoccupied with childhood and education. The middle third is typically devoted to family and career. Retirement comprises our final one third. This was a remarkable revelation and an inspiring point of view for me. If we truly have another 1/3 of our years ahead, then retirement is not just the end of a career, it is the beginning of another significant portion of our lives! I find myself quite stimulated and eager to open this new chapter. It begs the question, “What can I accomplish now?” And perhaps, “Is the best yet to come?” I love that possibility. Retirement for me was always on the horizon, but it seemed a mysterious and honestly frightening concept. Several questions loomed. Would I be able to afford it? What would be the optimum time to leave my job? And what would I DO in retirement? The money question, while paramount, was not a complicated riddle to me. My career was in banking so understanding the numbers was part of my DNA. I could fill the blog with advice, but the abridged version is to consult a good financial planner. It is a magical skill to match the resources to meet the needs. I found my advisor and together we navigated the sea of forecasting models to determine how the money could be there for that rainy day. This part of my puzzle fit into place. The appropriate time to leave a meaningful career also requires some thought. But most likely the hole we leave behind is not as large as we imagine it to be. I was becoming a dinosaur as the banking world changed dramatically. Online access is replacing brick and mortar locations, as well as any need for face-to-face transactions. When was the last time you walked into a bank? Therefore, leaving my profession was not difficult. It took less than 5 minutes to box the potted plant and the family pictures, steal my last handful of ballpoint pens, and turn off the light. Then the remaining question—What to do with my time?—was ready to be attacked with enthusiasm. I first jumped into a couple of projects that I wanted to tackle for my family. My wife, Pam, is still employed and has supported my retirement decision completely. To assuage her resentment at my staying at home each day, I volunteered to take over the cooking duties. Because I had practically no experience, I enrolled with a meal-kit provider. The kit arrives with the ingredients and complete instructions. Using this service expedited the learning process. I must admit to making many a greasy mess, a smoke-filled house, and a couple of over-spiced, undercooked results. But with practice I joined the ranks of those who can dice, mince, chop, and drizzle their way around the kitchen. I am now ready to fly solo without the meal kit. Armed with new skills, I have an interest that should be useful for my remaining years. More importantly, I am contributing to the household, which earns brownie points with my wife.  Leo the Labradoodle. Photo by Bob Cox. Leo the Labradoodle. Photo by Bob Cox. The other project was a graduation gift of sorts. My last-to-leave-the-house son was wrapping up his final semester in college and purchased an adorable Labradoodle puppy. He obviously had no clue as to the enormous responsibility of owning and training a dog. Not to mention, he was totally unprepared to care for a breed that quickly grew into a 50-pound small pony galloping around his apartment. With the aid of an online obedience program, I committed to an hour per day, four days a week for three months. I am pleased to say that Leo, still a bounding bundle of curls on legs, now responds to some basic commands. The online instruction was quite challenging, but in the end rewarding. I now have a talent I am anxious to use on a new dog of my own (which my wife says will only happen in my next life). Squeezed into the free time that I now enjoy are endless soccer games and cross country meets starring my grandchildren. At their young age it’s more like watching a swarm of bees, but far less worrisome. And I was recently elevated to first off the bench to pinch hit at babysitting the one-year-old. After a 25-year hiatus, I can still change a diaper, shoot a tiny spoon of applesauce into the clown’s mouth, and read Dr. Seuss like Morgan Freeman. I have learned, however, that my endurance is not the same as it once was and any dose of time with the grands is a wonderful recipe for a great night’s sleep. Regardless, I proudly wear my title of Poppy Cox with honor. A totally unplanned adventure began purely by chance. A former classmate saw a Facebook picture of me hiking with my family last summer. My friend is quite an avid hiking enthusiast and invited me to join him and a small group for a winter hike to Red River Gorge. The group included several other high school acquaintances I had not seen since graduation. This nature-loving assortment all have retirement in common and therefore the freedom to pick the best weather day to head to the woods. The hiking excursion was an awe-inspiring time spent reminiscing about the days gone by and where the last 40 years have taken us. This unofficial trekkers club has made over a dozen more hikes together and we keep tabs on each other via group texts. This is the retirement gift that keeps on giving. Hiking in the red river gorgePam travels regularly for her work. With my available time, I finally had the opportunity to join her for a business trip to New Mexico. While she attended a conference, I ventured out into the countryside near Santa Fe. I took a horseback trail ride at Ghost Ranch, the former home of artist Georgia O’Keefe. The scenery gave me a glimpse of some of the red hills and colorful cliffs used as reference material for her gorgeous paintings. The pastel layers that cut through the mountains were indescribable. I gained a whole new appreciation for her keen eye and ability to portray that beauty on canvas. I was struck by the contrast between the lush foliage and meandering streams of Red River Gorge and the lonesome cedar trees scattered among the endless desert-brown tones of the southwestern landscape. This was a solitary and peaceful adventure and fuel for my right-brained, creative side. The tale of my trip is a convenient segue to a use of time that really feeds my soul. We converted into an art studio the empty bedroom previously occupied by the now college-graduate dog owner. It is my plan to see if any real expertise can be excavated from repeated experiments with oil paints. If enjoyment is the gauge, I am already wildly successful. This is a contagious outlet that intrigues me and the most gratifying thing I have accomplished.

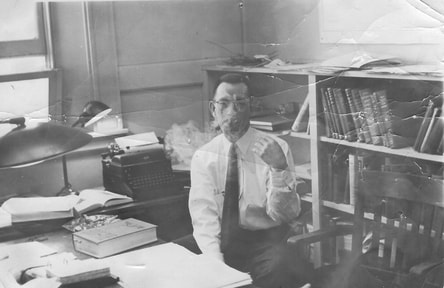

My generation will appreciate the reference: Simon & Garfunkel were on to something. I’ve got no deeds to do, no promises to keep I’m dappled and drowsy and ready to sleep Let the morning time drop all its petals on me Life, I love you, all is groovy (From “The 59th Street Bridge Song.” Lyrics by Paul Simon.) I must say that these first months of retirement have been overwhelming and joyous. I am truly relishing this time. The days are refreshingly original, frequently full, often exhausting and at the same time enriching. Reacquainting with old friends has been deeply meaningful in ways that I did not foresee. The reality of it all is still new and the structure is still forming. I don’t have any long-term predictions, but with a third of my life still ahead, perhaps the best IS still yet to come? Tomorrow, I think I will paint a highland cow. Or I may not. It’s totally up to me.  Professor John Campbell "Pud" Goodlett, my dad. Professor John Campbell "Pud" Goodlett, my dad. My father was a professor. My sister was a professor. My cousins were professors. So when J. D. Vance—possibly the most hated “man of letters” in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and Ohio’s current Republican nominee for U.S. Senate—dusted off the old Nixon trope “The professors are the enemy,” I was pert near required to take offense. Not that that was the most offensive thing that Vance has spewed during his gold star campaign of shame. That prize has to go to his declaration that women should stay in violent marriages for the sake of their children, comments he made in front of a California high school audience last year. But back to the diatribe against professors, who, I’ll just add, might also be women trying to survive abusive marriages. Vance, as most of you know, benefited from the instruction of professors at two of our nation’s most esteemed institutes of higher learning: Yale College of Law and The Ohio State University. His adopting Nixon’s old cry is disingenuous at best, dangerous and targeted at worst. Like so many of the most vocal haters and bigots on the populist right—Ted Cruz, Ron DeSantis, Josh Hawley, Donald Trump—Vance has an Ivy League pedigree. I hope his caustic comments about the teachers he studied under will prevent those who agree with him from taking up valuable space in our post-secondary classrooms. All of this pernicious rhetoric is part of a much more dastardly Republican plan to destroy public education and make empty-headed voters more susceptible to their lies and propaganda. And it’s working. Teachers are leaving their chosen profession in droves and fewer and fewer students are stepping up to fill the pipeline. States are drafting military veterans and current college students to stand in front of classrooms full of impressionable youngsters. State legislators are siphoning money away from public schools to fund charter schools that aren’t beholden to state education policies. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that school vouchers in Maine can be used to offset tuition for religious schools. What public school teachers can say in the classroom is being prescribed by state legislators and angry school board members. Books are being banned, library shelves emptied. Our democracy is under attack. Our schools are under siege. Our nation is breaking apart. And, still, J. D. Vance, in an effort to garner votes from Ohio’s electorate, stands on stage and excoriates the very teachers who gave him the confidence to pull himself up by his own bootstraps and escape the suffocating desperation of his family. Does he not realize that Ohio, with 195 degree-granting postsecondary institutions, may well have one of the highest professors per capita among U. S. states? And that all of those professors have extended family who vote? Perhaps he sought political advice from Kentucky’s one-term governor Matt Bevin, who antagonized teachers across the commonwealth with his persistent attacks on their integrity. Bevin attended Washington and Lee University, where he became fluent in Japanese and majored in East Asian Studies, solid preparation for leading a state where Toyota and its Japanese satellite companies changed the state’s economic trajectory. Like Vance, he clearly benefited from his professors’ tutelage. Vance may well win this election, although I’ll put my money on Democrat and current U.S. Congressman Tim Ryan. Maybe if Vance had paid more attention to his professors, he could run on facts rather than be enslaved to his party’s propaganda and lies. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed