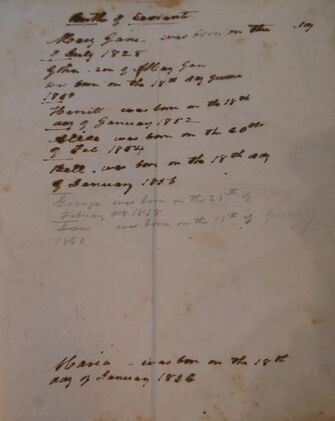

Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. Last month I found a small trove of family photos from the 1800s and early 1900s that I didn’t recall having seen before. I believe this is my great-grandmother, Mary Lake Barnes Board. It’s Black History Month, so it’s time for more reckoning. I have written freely in this blog about my family’s role in the lynching of a Black man, George Carter, in Paris, Ky., in 1901. I have written about my horror in learning about that incident. I wrote last summer about my rising fury at the unending injustice in this country that has led to the unconscionable loss of Black lives, tragedies that have been ongoing for generations but which have become more public with the advent of cell phone videos. I remain angry and disgusted with the lack of progress on the underlying issues that allow this to continue. I hope to write more about that before February comes to an end, and we give ourselves permission to stop thinking about these things until next February. Right now, however, I need to talk about the family Bible. I remember this Bible being displayed on a dropleaf cherry table in front of the picture window in our living room in Lawrenceburg, Ky., when I was a child. It was an enormous, handsome, heavy book, in good condition for a book of its age. I remember flipping through it; I remember noticing handwriting on some of the pages. But I don’t believe I could have told you what branch of my family it represented or anything about the people whose births and deaths and marriages had been noted. Recently a family member shared some photos she had taken of those pages. I immediately recognized that the Bible was yet another relic of my missing grandfather’s family, the grandfather who abandoned my mother shortly after her birth. The Bible was published in 1848, so the Bible first belonged to my grandfather Lyons Board’s grandparents, Dr. L. D. Barnes and his wife, Mary Parker Roseberry Barnes, of Paris, Ky. After all the research I—and others—have done into that family over the past ten years or so, I now recognize the names. Those of you who have read Next Train Out might, too. There’s the marriage of Dr. Barnes’ daughter, Mary Lake Barnes, to William Ellery Board, originally of Harrodsburg, in 1888. There’s the marriage of their only surviving son, William Lyons Board, to Nell Hardeman Marrs of Lawrenceburg, in 1920. There are the births—and the deaths—of all the children who didn’t live to adulthood, or didn’t even survive infancy.  And there are the births of the “servants.” The servants are identified only by first names: Mary Jane, John, Harriett, Alice, Bell, George, Dan, and Maria. The listing is separate from the “Family Record” listed in a fine hand on decorative pages. The handwriting on the servants page is less careful and difficult to read. It grieves me that I may not have all of the names correct. Another thing we have learned this year is how important it is to say their names. All of the servants were born between 1828 and 1860. All were born, I have to assume, into slavery. I don’t know that for certain, of course, And it’s possible they had been freed by the time they were listed in the family Bible. But any other scenario is hard to imagine in central Kentucky before the Civil War in a family of some status living in a county with a large population of slaves working expansive agricultural land. The fact that they are included in the Bible makes me want to believe that they were indeed considered members of the household and were treated gently and respectfully and were well loved by the Barnes family. None of that excuses the fact that some or all of them were at some point the property of the Barneses. I had already discovered some time ago that at least three of the four branches of my family once owned a small number of slaves, probably all doing domestic household work. I had already reckoned with that in some small way. It was not a surprise to discover this listing of the Barnes family servants. But it remains painful to see the evidence handwritten in such a personal way in the family Bible. Many of us from the South share a similar family history. It’s remote to us now. We’re talking about more than 150 years ago, after all. Nonetheless, I feel it’s important not to deny our intimate connections—no matter how tenuous, no matter how seemingly innocent—to the national shame our country has to bear, and bear witness to. My family played a role. The Bible tells me so.

4 Comments

Anne Simmons

2/2/2021 09:47:12 pm

Beautiful tribute for Black History Month.

Reply

Tessa Bishop Hoggard

2/3/2021 11:41:38 am

What a precious gift your ancestors have given you! That gift is knowing the fabric of your soul, the threads that intertwined and weaved into your DNA and makes you unique. That gift is a family story from centuries past which you and future generations can declare and celebrate. Though February is a month set aside to commemorate and reflect on African American contributions to our civilization, it's also important to note that history is blinded to color...history belongs to everyone regardless of race, creed, or religion. Thanks for sharing, Sallie.

Reply

Joseph Anthony

2/3/2021 04:49:41 pm

Reading The Hemmings of Monticello last year or so, I was amazed at how complicated some slavery relations were. The Hemmings and Jefferson included uncles, cousins, in-laws, children, and many interchanges. The intimacy actually made the slavery seem worse to me---since the whole human interchange to be punctuated by the word "property" just shocked and repelled. I wonder if your family had some of that same intimacy and the same mixture of human and horror.

Reply

Sallie Showalter

2/3/2021 05:44:11 pm

You know, my family was a family like any other, and given how common those sorts of complications and liaisons were at the time, I have to suspect that could well have been true for them also--although I have no documented evidence of it. And, like most families, I feel we have certainly unearthed our share of that "mixture of human and horror."

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed