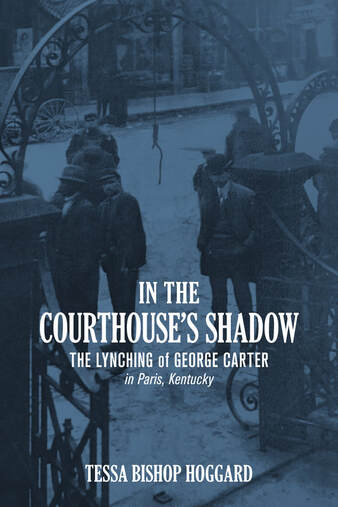

The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. The Greenwood district after the Tulsa massacre in June 1921. National Red Cross Photo Collection—Library of Congress. As I started working on Next Train Out, I knew that racial conflict had to be a theme of the novel. It seemed clear to me that the trajectory of Lyons Board’s life had to be predicated in part on his role, as an eight-year-old boy, in having a Black man lynched in his hometown, Paris, Ky., in 1901. As I researched the various cities and towns where my grandfather eventually lived, I found plenty of instances of racial unrest in their histories: mob violence, riots, lynchings, the obliteration of sections of towns where Blacks lived and prospered. Soon I began to better grasp the bigger picture, that the whole country was awash in deadly racial conflict just after World War I, when Black soldiers returned home expecting opportunities and respect in return for serving their country in the trenches in Europe. Instead, they found resentment and violence stoked by the belief among some white citizens that these returning veterans threatened their jobs and their status in the community. I learned about the Red Summer of 1919, which made me realize how widespread these race problems were. These confrontations were not isolated to the Deep South. They erupted in our nation’s capital, in Chicago, in New York and Omaha—in at least 60 locations from Arizona to Connecticut. How this anger and suspicion manifested itself in towns like Corbin, Ky., and Springfield, Ohio, are part of Lyons’ story. As we all now know, an area referred to as Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Okla., waited until 1921 for its turn at center stage. On June 1, after 16 hours of horror, more than a thousand homes and scores of businesses had been incinerated. Somewhere between 100 and 300 people had been murdered. Thousands of Black survivors were then corralled into a detention camp of sorts and assigned forced labor cleaning up the mess the violent white mob had created. Before June 2020, when President Trump landed in Tulsa for a campaign rally originally scheduled to take place on Juneteenth, few Americans knew the lurid history of Black Wall Street. The facts had been suppressed, kept out of classrooms, out of the news, out of polite conversation. Black families in Tulsa passed down stories of violence and terror and escape—or stories of family members never seen again, their fates unknown. Few public officials dared recognize what had happened to all those people and their livelihoods and their property and their wealth. This year, on its 100th anniversary, the entire nation has been awakened to Tulsa’s tragic history. LeBron James produced a documentary—one of many. Tom Hanks wrote an op-ed. HBO made its Watchmen series accessible to more viewers. News forums of all types reported on the anniversary. Survivors of the massacre—all more than 100 years old--testified before Congress and met with President Biden. Under the leadership of Tulsa’s young white Republican mayor, G. T. Bynum, archaeologists have resumed the search for mass graves that had finally begun last summer. How a community like Tulsa now, finally, begins to reckon with its history is significant for all of us. We as a nation, as a collection of human beings, must break the silence we have permitted ourselves for generations and acknowledge how gravely we have wronged indigenous peoples, Blacks, and other minorities. How we blithely destroyed their culture, their history, their identities, and their lives. Acknowledging the truth is a start. Reporting historical facts is essential. Engaging in respectful, compassionate, and sensible discussion can prompt healing. Some communities—and even the U.S. Congress—are now beginning to discuss what reparations might look like. Other communities first need to simply acknowledge both the shame and the pain that have churned for decades among their citizens. When I first met with Jim Bannister, the great-nephew of the man lynched because of an alleged incident with my great-grandmother, he made it clear that it was the silence that weighed most heavily on him. He had tried to learn more about the lynching of George Carter, but no one would talk about it. His elders wouldn’t talk about it. The Black community wouldn’t talk about it. Fear and shame and ongoing oppression had kept everyone close-mouthed for generations. The emotional damage accrued. The human damage. The not knowing. The not understanding.  With her book In the Courthouse’s Shadow, Tessa Bishop Hoggard provided the key that Jim needed to open the door to his family’s history. She pulled his story out of the shadows. Jim has told me repeatedly that he feels an extra spring in his step now that he knows the facts. He has found a peace that had eluded him all of his eighty years. In her interview with Tom Martin on WEKU’s Eastern Standard program this week, Tessa said, “As we peer into our history, hate crimes were a common daily occurrence….Accountability and consequences were absent. There was only silence. This silence is a form of complicity….Today is the time for acknowledgment and healing. Let the healing begin.” (Listen to the 10-minute interview.) We have to acknowledge our difficult history. We have to face what happened. And then we have to consider the steps, both small and large, that we can take to heal the wounds that will only continue to fester if we stubbornly ignore them.  This year, on the morning of Juneteenth (Saturday, June 19), I’ll have copies of Tessa’s book and my novel available for sale at the Lexington Farmers Market at Tandy Centennial Park and Pavilion in downtown Lexington, Ky. In August 2020, the citizens of Lexington agreed to rename Cheapside Park, the city’s nineteenth-century slave auction block and one of the largest slave markets in the South, the Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park, honoring the freed slave who did masonry work for many of Lexington’s landmarks, including laying the brick for the nearby historic Fayette County courthouse, built in 1899. One of the organizers of the “Take Back Cheapside” campaign, DeBraun Thomas, said at the time: “Henry A. Tandy Centennial Park is one of the first of many steps towards healing and reconciliation.” Fittingly, I’ll be at the Farmers Market as part of the Carnegie Center’s Homegrown Authors program. Tandy had a hand in the construction of Lexington’s beautiful neoclassical Carnegie Library on West Second Street in 1906, now the home of the Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning. If you’re in Lexington that morning, stop by and we can continue this conversation.

1 Comment

Joan Cullen

6/10/2021 11:56:52 pm

Thank you for this post.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed