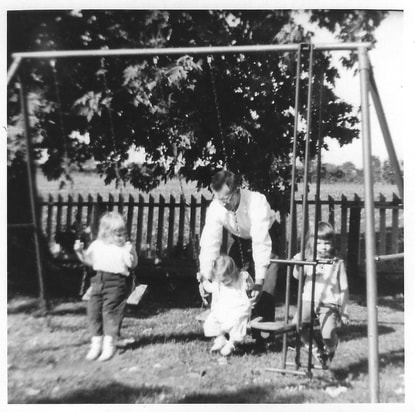

My dad with, from left, my cousin Martha, me, and my sister Ginny. My dad with, from left, my cousin Martha, me, and my sister Ginny. I’m reading Regina Robertson’s excellent collection of essays detailing the stories of daughters who have lost their fathers, whether to death, divorce, or abandonment. The book, He Never Came Home, includes a foreword by Joy-Ann Reid, who writes: "[A]s the women who share their stories in this book reveal, how that loss shapes you depends less on the substance of the man who’s gone away or on his manner of leaving—whether through addiction and self-harm, or suicide, or apparent uninterest, or the unyielding, icy authority of mortal disease—and more on what the loss created in the mourner: in some cases, resilience; in others, self-doubt; in still others, a determination to move on and to be whole, regardless." I am a second-generation daughter who grew up without a father. As I relayed in the afterword to The Last Resort, my father, from all outward appearances a healthy man, died unexpectedly of a heart attack when I was 7, leaving behind my mother, my older sister, and me. Thinking back, I grew up among strong women: my mother and my aunts—my father’s sisters-in-law—in particular. Their husbands, my father’s brothers, were still around, but my father’s death, or perhaps a genetic inclination to depression, seemed to accelerate their natural withdrawal from the larger family. One generation back, my mother’s father abandoned his wife and newborn daughter in 1921 and simply disappeared. As far as we know, the family never heard from him again. My mother, though she rarely mentioned it, felt acutely her whole life the grief and anger that arose from a father who evidently didn’t care enough to stick around and never even bothered to find out what happened to her. I have to think that watching her two daughters grow up without a father, just as she had, compounded her pain. It wasn’t until the advent of the Internet, after my mother’s death, that we were able to drudge up simple public records that tracked his surprising odyssey around the country. But that’s fodder for my next book. As Ms. Reid’s words suggest, we all handle these absences differently. Certainly a number of factors affect our reactions, but I have come to believe that the age of the child at the time of the loss makes a critical difference. I suppose I can argue that I was young enough not to have been as attached to my father as my older sister was. He traveled a lot with his work and wasn’t around the house much. My sister identified more closely with him as a child, and I believe she suffered more than I did after he died. Not having a father around seemed to make me more determined to prove that I was the strong member of the family who could pick up the slack. Despite my tiny size, I mowed the yard. I trimmed the hedges. I shoveled the driveway. In fact, my mother was quite distressed when she was unable to convince the administrators at my high school that I should be able to take “shop,” as we called industrial arts back then. But girls weren’t allowed in that class. I think I was secretly relieved. I discovered later I have no spatial aptitude and no real interest in learning how to use tools. But I was the one who could soldier on. My mother quietly fell into a sort of depression that gave her permission to retreat into mysteries and bourbon each evening after she got through a day’s work. My sister lashed out in anger and bitterness at the world’s stupidity and injustices. I just plugged along, trying my best to do what I was supposed to do. We all deal with grief differently. But it takes its toll on all of us. Ms. Robertson’s book provides an intimate and sometimes painful insight into how daughters mourn their fathers. It’s a book I would recommend to every father and every man who wants to be a father. You can’t miss the key message: All you dads out there? You really, really matter.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed