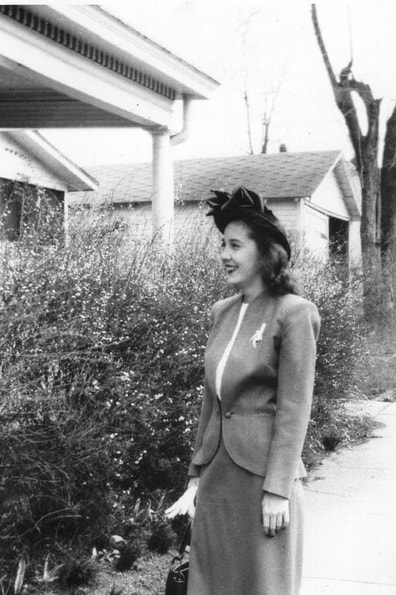

Mary Marrs Board in Lawrenceburg in April 1947, shortly before she married Pud Goodlett. Mary Marrs Board in Lawrenceburg in April 1947, shortly before she married Pud Goodlett. Tim Cooper of Oakdale, Minn., responds to the recent post Whistling Past the Graveyard. If you would like to share your thoughts on Clearing the Fog, contact us here. T. S. Eliot once wrote, “Great works of art always mean more than they are capable of expressing.” Whenever I return to Pud Goodlett’s journals in The Last Resort and reread his thoughts as a young man, I am reminded of Eliot’s quote, of how even something as apparently straightforward and unencumbered as a camp logbook can resonate with unexpected intent and purpose. I am particularly cognizant of Goodlett’s love of place and family, and how scholarly success never weakened his ties to Kentucky. When I read Sallie Showalter’s recent blog—which mirrors this attachment to family and place—I realized there must be a mystical connection between people and location that sometimes transcends all else. As I was growing up, my family moved a dozen times to a dozen different states while my parents pursued graduate degrees and visiting professorships. I learned early not to form an attachment to a place. I am also the only child of an only child, and I can count my remaining relatives on one hand. I am watching my mother die from Parkinson’s disease. So I use the term “mystical” deliberately when thinking of those who experience this ineffable pull of family and place. As a young man, I was unaware of its power. As I contemplate the latter phases of my life, as I extricate myself from the shackles of my career, I yearn for those ties to a constant place and to people who knew me way back when. That, in a roundabout way, brings me to Pud’s wife, Mary Marrs, and my brief encounters with her when I was young. I recall her as a woman of unassailable beauty and grace. She, too, served her country during WWII by leaving her small-town home in central Kentucky and going to work for the Navy in Hawaii. (A tough gig, that.) Like many of the more fortunate members of her generation, she returned to her roots when the conflict concluded.  Mary Marrs around the time Tim Cooper met her. Mary Marrs around the time Tim Cooper met her. I must have been 15 years old, a friend of her older daughter, when I met her. She always treated me with the utmost kindness. One story will suffice: I’m not sure where her two daughters were, but she and I found ourselves in her kitchen, drinking coffee early one morning. We must have talked for an hour, and while I don’t remember the thread of our conversation, I do recall that she took me—a 15-year-old boy and all that that entails—seriously. I also recall her discussing her deceased husband and telling me how I would have liked him. It was only years later, after the death of my own father at an absurdly young age, that I recognized in the eyes of my mother the look on Mrs. Goodlett’s face during that talk: a look of bereavement, confusion, controlled anger, and a sadness that cannot be articulated. And just as Mary Marrs had returned to Lawrenceburg from her home in Maryland after Dr. Goodlett’s passing, so my own mother left Kentucky and returned to her family in Minnesota after my father’s death. The pull of place, of family, of familiarity surmounted the grip of artificial roots. And while we could argue whether these two women made the right decision, who can argue with the gravitational pull that lured them home? Camus wrote: “There are places where the mind dies so that a truth which is its very denial can be born.” The human condition is absurd: we plan, we strive, we rely on rational, systematic thought to live. And yet, our mortality tells us that our existence is provisional and transitory; it is irrational. We carve out careers, and they crumble into insignificance when we visit the gravesites of our relatives; we remember our deceased loved ones in their vibrant youth, and yet we somehow live longer than they; we live in exciting locales among interesting friends, and yet our profound meaning comes from our place of origin. It is, indeed, when we delve into and accept the irrational—the “dying of the mind”—that we find our true selves, our “truth.” And for those, like me, who do not have roots, who do not have a family or place which circles the wagons and protects us, this irrational absurdity compels us to act, to rebel, to define ourselves by our actions, by our choices. Pud Goodlett, writing home about what he witnessed at the Nuremburg war crimes trials, wonders if his brother Vincent, an attorney who had served his country in England, would have found the events interesting. And his widow, talking about her deceased husband to a teen-age boy as though this untamed youth were the most important person she had ever met, perhaps unwittingly reveals the most profound truth she knows: family and place are what bind us to this earth, and to each other.

2 Comments

Bob McWilliams

8/5/2018 08:11:18 pm

Wow, that is beautifully written piece. Part ode, part ellegy, part prose and part poem.

Reply

Timothy Cooper

8/5/2018 09:48:52 pm

Bob:

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed