|

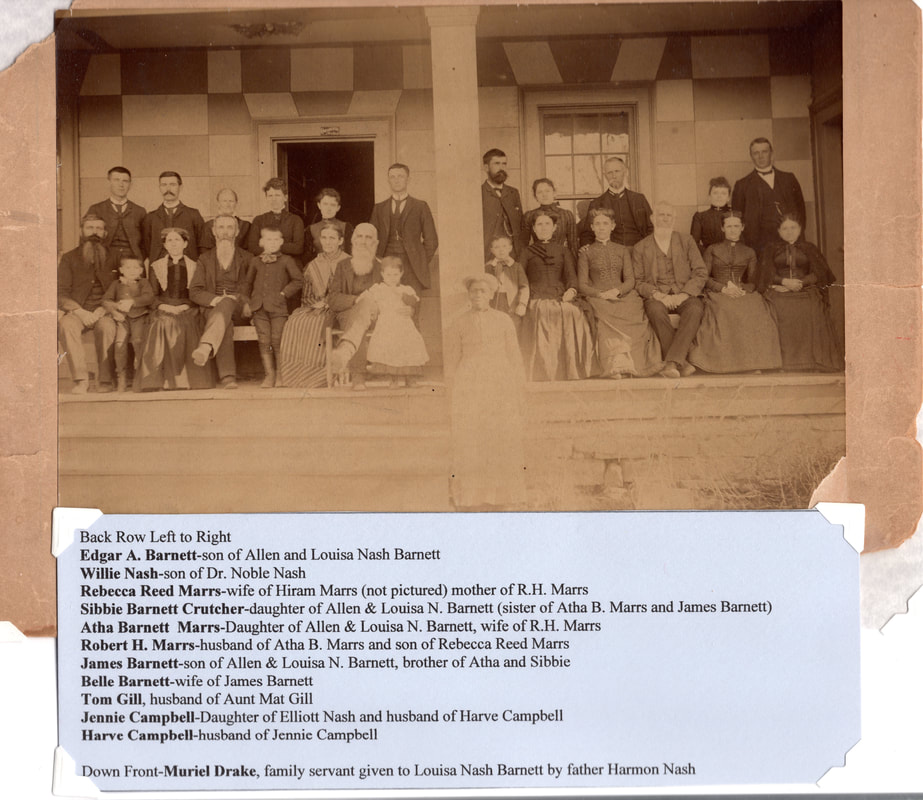

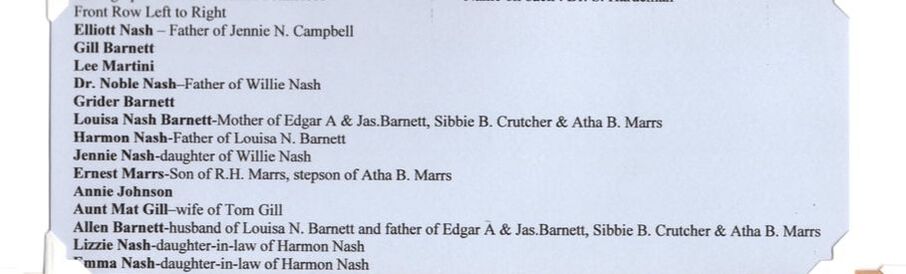

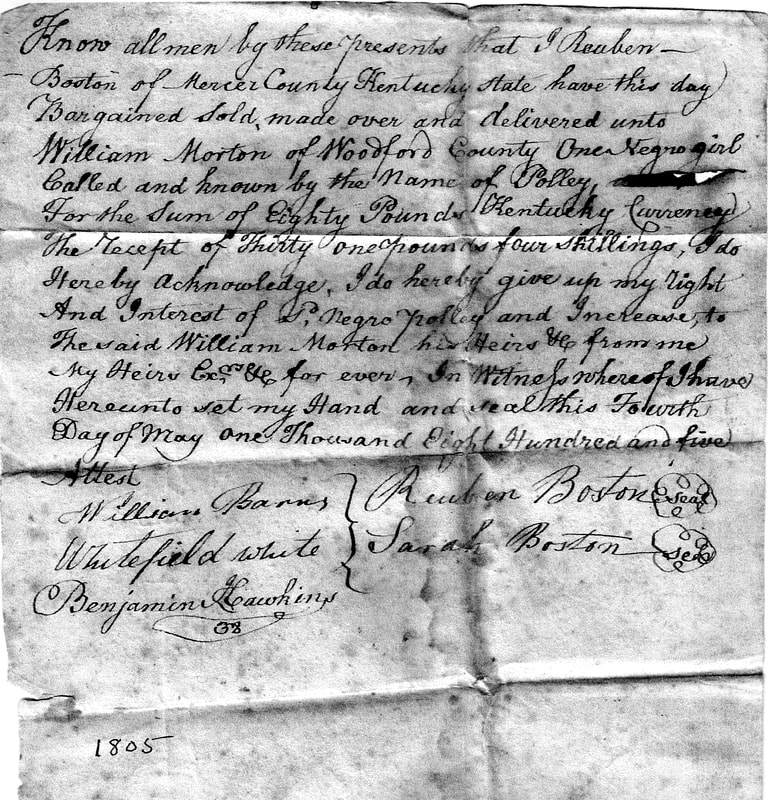

When I was in second grade, I vividly remember coming home and declaring to my mother that I intended to marry my classmate David Oldham. He was handsome, smart, and debonair (or at least that’s how I recall him more than 50 years later). My mother frowned. Always the pragmatist, never the romantic, she said, “But you can’t marry David, Sallie. He’s colored.” I was outraged. I was defiant. I thought my mother was just trying to deny me the wedded bliss that I imagined. But it was Baltimore in 1966. Loving v. Virginia wouldn’t be decided until 1967. Mother knew best. The following spring I watched as the city bused black children from their inner-city homes to P.S. 212, my school in northeast Baltimore. Even at seven years old I could feel their terror. They couldn’t sit comfortably in their seats. Their wide eyes darted around the room. They didn’t speak. I was gone shortly after that—before the end of the school year and before the Baltimore riots—whisked away to my own foreign world in Kentucky. I did not go easily. I hid in my bedroom closet, hoping my mother would leave me behind so I could stay near my friends. These memories have come back recently as the nation has flirted with another conversation about busing. We’re talking again about reparations. And this month we’re acknowledging the 400th anniversary of the first African slaves being brought to our shores. As I’ve dug into my family history over the past few years, I’ve discovered evidence that the ancestors of at least three of my four grandparents owned slaves. They all lived in Kentucky or Virginia or Tennessee. Most of the families had come to this land from Great Britain well before we had gained our independence. I don’t know that any of my ancestors were sizable landowners, but they evidently elected to use slave labor to keep the household or small farm running. At first, I was shocked. Then I felt resigned. Those of us whose families have been here longest may have the most to explain. While everyone in this country benefited from slave labor, we are the ones who claimed ownership of other human beings. We are the ones who were here to grumble and complain as each new ethnic group came to this country fleeing famine or religious persecution or genocide. Or arrived here simply seeking a better life. Today we malign the immigrants who knock on our door looking for refuge, for work, for a future. We blame the ills of this country on the “huddled masses” who come here seeking hope, while we quietly benefit from the work only they are willing to do. But perhaps it’s not recent immigrants, but those of us whose ancestors arrived here earliest who carry the biggest burden. We’re the ones who now need to demonstrate what we can offer this country. How we can make it whole. How we can repay the gifts we’ve received. That’s our public charge.

1 Comment

Ed Lawrence

8/24/2019 10:29:56 pm

When I was about nine, (1958) I did an oral history with my grandmother. Our family settled in Bourbon County in 1785. I asked her about what her father did for a living and grandfather, and great grandfather and so on up the ancestral chain. some were farmers, some millers, some distillers. I forget how far we got up the chain, but when I asked her what he did, she replied, "He had five slaves." So I asked her again, "But what did he do?" To which she replied, "He had five slaves." In my adult life, I have come to understand why she answered me that way, but I am still unsure of what to do with that information.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed