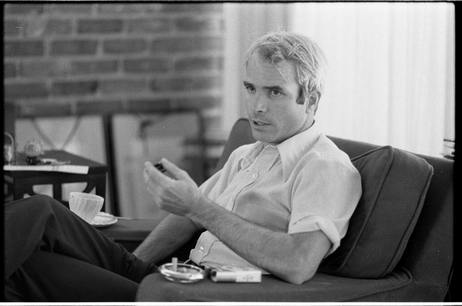

Lt. Comdr. John S. McCain during an interview after his return to the U.S., April 24, 1973. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Lt. Comdr. John S. McCain during an interview after his return to the U.S., April 24, 1973. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. After reading last week's post Seductive Silence, Tim Cooper, of Oakdale, Minn., has been thinking about how a liberal arts education could encourage the empathy and resilience we so desperately need. If you would like to submit a blog post for Clearing the Fog, contact us here. Like many Americans, I was riveted to the television during the services for the late Sen. John McCain. It was a brief, and it appears now ephemeral, moment when we were reminded of the heroes among us who have been willing to put country above party or personal interests. My favorite McCain story related how a prisoner in the cell next to McCain’s at the Hanoi Hilton used a surreptitious tapping code to teach McCain the Robert Service poem “The Cremation of Sam McGee.” McCain’s daughter Meghan shared how he later recited the somewhat grisly poem to his future wife on their first date. That was my first glimpse into the Renaissance man who was John McCain. I learned that his favorite author was Hemingway and his favorite novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. I learned that McCain regularly read novels and enjoyed writing. While in the U.S. Navy, I attended classes at the Naval War College. The highlight for me was a lecture by Admiral James Stockdale, a man who had endured eight years as a prisoner of war, also in the infamous Hanoi Hilton. During the lecture, Stockdale revealed the key to his survival: His study of moral philosophy—particularly the Roman Stoics—while a student at Stanford had provided food for his mind during those endless days of tedium and fear. He was able to draw from his own intellectual reserves to provide the discipline and resilience he so desperately needed and avoid succumbing to the darkness. As president of the Naval War College, Stockdale later instituted classes in philosophy, literature, and history. For him, study of the liberal arts was not just a path to enlightenment; it could well be the key for another young serviceman’s survival. It struck me that these two national heroes, either by their own habits or by their professional influence, were evangelists for the value of education in the humanities. We all face times when we need to draw from our knowledge or understanding of the human condition to survive a struggle that seems poised to drop us to our knees. Sadly, a quick perusal of recent news articles reveals that the classic liberal arts curriculum is being relegated to history. Colleges in the University of Wisconsin system have eliminated English, sociology, political science, and history majors from their campuses. In their stead, these universities offer business, science, engineering, and computer technology centers. In Lexington, Bryan Station High School has restructured its curriculum as the Academies of Lexington, an initiative dedicated to preparing students in grades 10 through 12 for future careers, careers that range from electrician to chef to computer programmer to paramedic. As I understand this new initiative, all curricular content is filtered through the lens of the student’s career aspiration. Meanwhile, Eastern Kentucky University has made its marching band a peripheral “activity” separate from the school of music, eliminating its academic affiliation. My father, a man who abandoned hopes of a pro baseball career to become a professor in the music department at EKU (until his premature death in 1988), always promoted the marching band’s democratic pull, its ability to connect students from a variety of majors and interests and expand their experience with the arts. These insidious changes also reached the parochial school where I taught for two decades before retiring in June. Students entering this institution are now encouraged to declare in middle school whether they would like to work toward a “business certification” that would be attached to their high school diploma. The goal is that, by taking business classes, students will attain what Bryan Station identifies as the ability to see real world applications in what they learn in the classroom. But what have these students lost? At my former school, signing up for the business classes extinguishes the option of taking band, chorus, art, or photography. By devolving the marching band into a student activity, EKU has lessened the connection non-music majors had to an acclaimed music school. And by emphasizing the utilitarian nature of learning, Bryan Station’s program has obviated the concept of learning for learning’s sake. My best friend during my undergraduate days at the University of Minnesota was a young man from rural Wisconsin who was interested in literature, theater, classical music, blues, jazz, and pop-culture. Kurt was also a business major. During his last two quarters at the “U,” Kurt contacted numerous companies about employment. Caterpillar Corporation called Kurt to arrange an all-day interview at their corporate headquarters in Peoria, Ill. Kurt asked me to drive down with him. After his very long day, I asked Kurt how the interviews had gone. He shook his head and responded, “It’s the craziest thing. They never once asked me about business. Instead, they asked about what I read, what I think about, what plays I had recently seen, whether I volunteer and why, and so on.” A week later, when a representative from Caterpillar called to offer him the job, Kurt asked about the peculiar nature of the interviews. The representative responded simply and directly: “We can train anybody about our business, but we cannot teach people to be well-rounded.” Readers of The Last Resort will recall that Pud Goodlett read Walden and Ridpath’s history, but also works by humorist James Thurber and contemporary popular fiction. They were all outside his academic interests in plant geography and ecology. In The Last Resort, are we seeing the last of an era that encouraged Renaissance men? Have we relegated all that Pud and my dad were to myth, and have we replaced their world view with one regulated by market considerations? Have Senator McCain, Admiral Stockdale, and my friend Kurt become quaint examples of an ethic that no longer holds sway? I am distressed that not only have colleges and universities become training grounds for careers, but so, too, have high schools. I am distressed that many future business leaders, politicians, and academics have not been exposed to a liberal arts education and have, instead, become technocrats in their own professions. And I am most especially distressed that the understanding, empathy, and, dare I say it, behavioral standards acquired from embracing moral philosophy, literature, and the creative arts seem to have been lost to the dictates of economic empowerment.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed