|

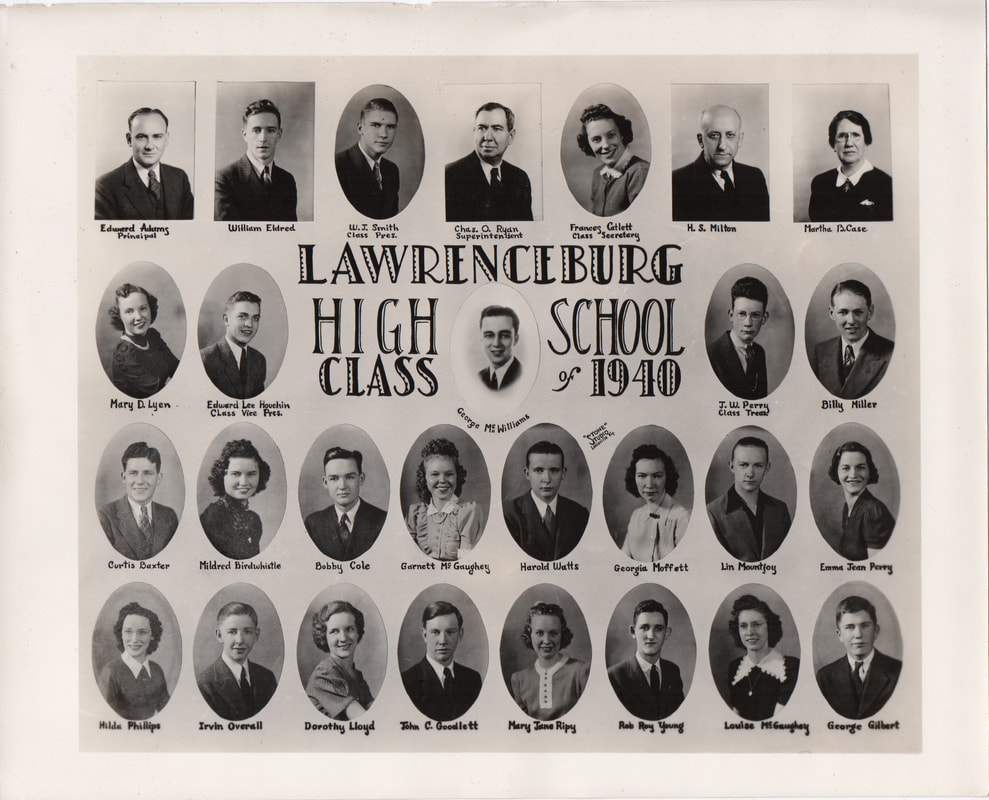

A few months after my father died, after we had moved from Baltimore and settled in our new home in Kentucky, I woke up late one evening in a panic. I thought I was going to die. I was certain of it. I don’t remember if I had a sensation that my heart was failing me, or if I just had a sense of dread. I was eight years old. I remember sitting with my mother on her bed as she called the doctor. I don’t recall if I was crying. I expect I was frightened. I know my mother must have felt a sense of panic and helplessness. Thankfully, our doctor at the time, George Gilbert, was not only a small-town doctor (who later made regular house calls to soothe my troublesome earaches with shots of penicillin), he had also been a classmate of my father’s. He had known both my parents well. After briefly explaining the situation to him, my mother handed the phone to me. I listened as he tried to reassure me that everything was OK. I don’t think I believed him. But I understood even then that death was inevitable, and if it was my time, it was my time. This long-repressed scene played out again in my mind as I heard details of the Inspector General’s report relating to the harm done to small children who were separated from their parents upon arriving at our southern border. One child reported, “I can’t feel my heart.” Another said, “every heartbeat hurts.” These were explained as physical manifestations of the emotional pain the separation had caused the children. One story in particular stuck with me. “A 7- or 8-year-old boy was separated from his father, without any explanation as to why the separation occurred. The child was under the delusion that his father had been killed and believed that he would also be killed. This child ultimately required emergency psychiatric care to address his mental health distress.” I suppose it makes sense that young children who identify with their parents might expect that their parent’s fate could be their own. If parents can’t protect themselves from some harm—arrest, separation, death—how can they protect their children from these same terrors? I am still amazed when I wake up each morning. I have always expected to share my father’s fate. But I’m old now. I’ve outlived him by 16 years. I did not succumb prematurely. Nonetheless, this is a tiny trauma I have carried throughout my life as a result of losing a parent unexpectedly at a young age—at the same age as the boy separated from his dad. Yet I knew what happened to my father. I had a loving mother who cared for me in a secure home. I cannot imagine the lifelong repercussions and insecurities this young boy might face. For me, this is a reminder that all this country is doing in the name of “policy” is personal. Our separating families at the border affects all of us. Our denying climate change and rolling back common-sense regulations affects all of us. Our refusal to restrict widespread access to military-style weapons affects all of us. We will feel the pain of the Central American refugees, the residents of low-lying coastal communities, and the families who have had loved ones slaughtered. We all share common humanity. We all respond to loss and fear the same way. I had promised that I would not revisit my “father loss” theme again so soon, but circumstances keep pushing me back to that well. If that early experience is what connects me to the world at large, then its value—and its pain—is a privilege that I need to share.

1 Comment

Timothy Cooper

9/6/2019 08:21:31 am

Sallie:

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed