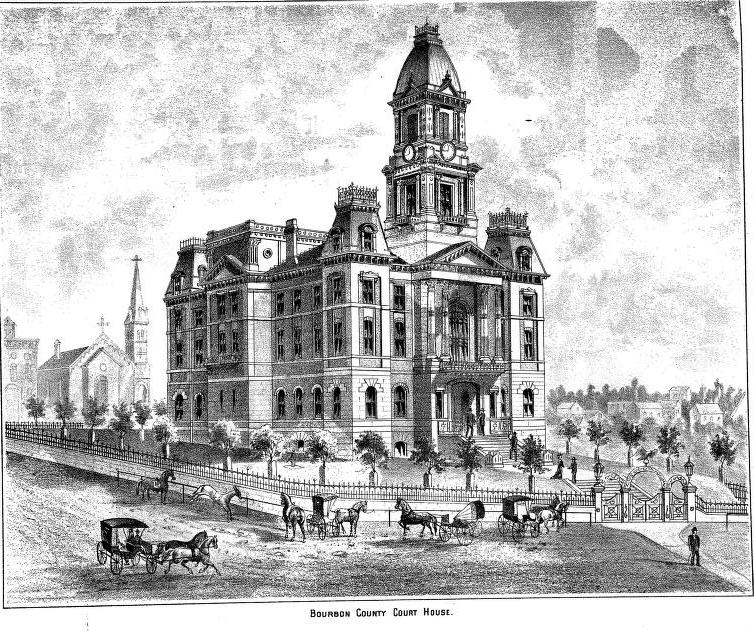

The Bourbon County Courthouse, which was destroyed by fire on October 19, 1901, just eight months after the arched gate at the bottom right was used to lynch George Carter. The citizens of Paris preserved the iron gate after the fire and it still stands adjacent to a historic building in downtown Paris. As I’ve worked on my novel over the past three years, I’ve dedicated large chunks of time to researching or writing about the first half of the 20th century. I’ve tried to grasp the cultural and societal impact of two World Wars, the Great Depression, the rise of labor unions, and expanded access to telephones and automobiles. I’ve thought about how different parts of the country—from Miami to Toledo to the coal towns of Eastern Kentucky—responded to those changes.

That’s a tall order, and I’m certain I’ve barely scratched the surface of all I need to know. Nonetheless, I’ve frequently found myself immersed in another place and time—worlds that one would think are quite different from our 21st-century reality. So I was somewhat surprised when I opened the Sunday Herald-Leader on November 24 and discovered two articles on the opinion page addressing a theme that runs through my novel. In one, Western Kentucky native LaTonia Jones writes about her youth in Paducah, where she played innocently in the cool grass on the very site where two black men, Brack Kinley and Luther Durrett, were lynched on October 13, 1916. In the other, University of Kentucky Ph.D. candidate Carson Benn recognizes the 100th anniversary of the efforts of the citizens of Corbin, Ky., on October 30, 1919, to expel all the black residents from their town. Unfortunately, the term “lynching,” and all the ugly and unforgivable history it represents, has recently been a part of our national conversation. And it was only a few short months ago that we were talking about sending certain people in our country back where they came from. It appears that in the 100+ years that have intervened since the events memorialized in these articles we have progressed very little. That we would resurrect these expressions and use them for personal advancement is unthinkable. That we still shy away from the conversations necessary to address simmering resentments is inexcusable. Can we ever find a way to embrace all our fellow citizens equally and justly? My grandfather, whose life is fictionalized in Next Train Out, worked at a pharmacy in Corbin in 1914. In a scene in the novel, he returns to Corbin in 1934 and reflects on this shameful event in the town’s history, an event he views through the lens of a World War I veteran who trained alongside black recruits. At this point, he has also spent a lifetime coming to grips with the perverted justice he witnessed as an eight-year-old boy in Paris, Ky.—the same sort of justice that LaTonia Jones’ ancestors witnessed. Evidently we still have much to learn from our history. Almost despite ourselves, we continue to find ways to inflict harm on each other, wittingly or unwittingly. And that is why it is so important that Ms. Jones and Mr. Benn and others continue to remind us of our past. Burying it will only let the cancer grow. Bringing it into the light, as is the goal of the Sunup Initiative in Corbin, is how we may best be able to change course.

2 Comments

Barbara Fallis

12/2/2019 06:34:44 pm

As you all know I am not a writer but want to share this experience I had while volunteering at the historic Dinsmore Homestead in Burlington, Ky. Beware, I write the same way I talk so I'll now ramble on. Last month an exceptionally large group of 3rd graders were there to learn about the 1850's compared to today. They separated into groups over 6 stations, from the log cook cabin, the main house, up the hill to the family graveyard in the woods, etc. We try to keep to the timing the school requires. My group was in the expansive front yard to play games (metal hoops with wooden sticks) and games all made of wood and string. In my intro Q and A we talked about toys of the 1850's- who could afford them. The Dinsmore family had money but were very rural, the tenant farmers earned only$12.00/month in the summer but the slaves were not paid nor could leave to find better work, etc. The kids played and always have fun. As my group was leaving this cute African American boy looked up at me and asked "How do you become a slave?". I think I said a few words, as the group had to stay together to go elsewhere. How could I have distilled the American history of slavery in 3 seconds. His words have haunted me...his beautiful brown doe eyes...so innocent.

Reply

Sallie Showalter

6/14/2020 08:59:19 pm

This is a note for Ms. Hoggard: If you will view the Murky Press CONTACT page and send me a brief message, we can then correspond via email. I'm afraid I don't have the specific information you are looking for, but I am very interested in your project. Thank you for reaching out.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed