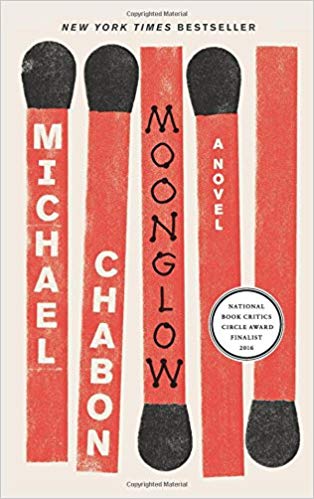

Nearly two years ago a friend sent me a review of Michael Chabon’s 2016 novel Moonglow. In the book, Chabon pieces together the remarkable life of his crotchety grandfather, a World War II veteran and a rocket aficionado. One reviewer, Hamilton Cain, in O, The Oprah Magazine, calls it “an exuberant meld of fiction and family history.” I realized immediately that I needed to read this book. It’s an amazing story of family secrets only revealed when painkillers loosen the grandfather’s inhibitions—and his lips—during the last days of his life. There are phantasmagoric tales of mental illness, war crimes, civilian crimes, the space age, Jewish slums, and Florida retirement communities. And if you’re familiar with Chabon’s work, you know it’s brilliantly written. I highly recommend it. As I’ve worked on my own novel about a somewhat mysterious grandfather, I’ve frequently returned to the words Chabon wrote in his Author’s Note: “In preparing this memoir, I have stuck to facts except when facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it. Wherever liberties have been taken with names, dates, places, events, and conversations, or with the identities, motivations, and interrelationships of family members and historical personages, the reader is assured that they have been taken with due abandon.” One of my chief struggles has stemmed from my desire to reveal all that I have learned about my ancestors and about the times they lived in. I know this is not what the reader of a work of fiction wants. And I have worked assiduously to rein in those tendencies. I recognize that some of my best characters may be the ones I invented whole cloth because I didn’t have the details of their lives available to me. And, of course, all conversations, all motivations, all emotional reactions were fabricated. With no family letters or other personal artifacts, how could I know any of that? I sometimes remind myself that the imagination can be the best conduit for the truth. There’s a reason Chabon’s note ends with the words “due abandon.” However, I freely confess that the facts have largely dictated the broad strokes of the narrative. After all, I started out wanting to tell the story of my grandfather’s life. And there were some truly eye-popping discoveries that I hope have led to a compelling story line. But at times I allowed myself to get bogged down in details that a general audience will not care about. With help from my early readers, I have trimmed a good bit of that out. I know I still have a little more that needs to go. It always helps to reread Chabon’s words and remember how critical it is to stick with facts “except when facts [refuse] to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it.” It is, after all, a work of fiction--“Scout’s honor,” as Chabon defiantly states in the disclaimer for his memoir.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed