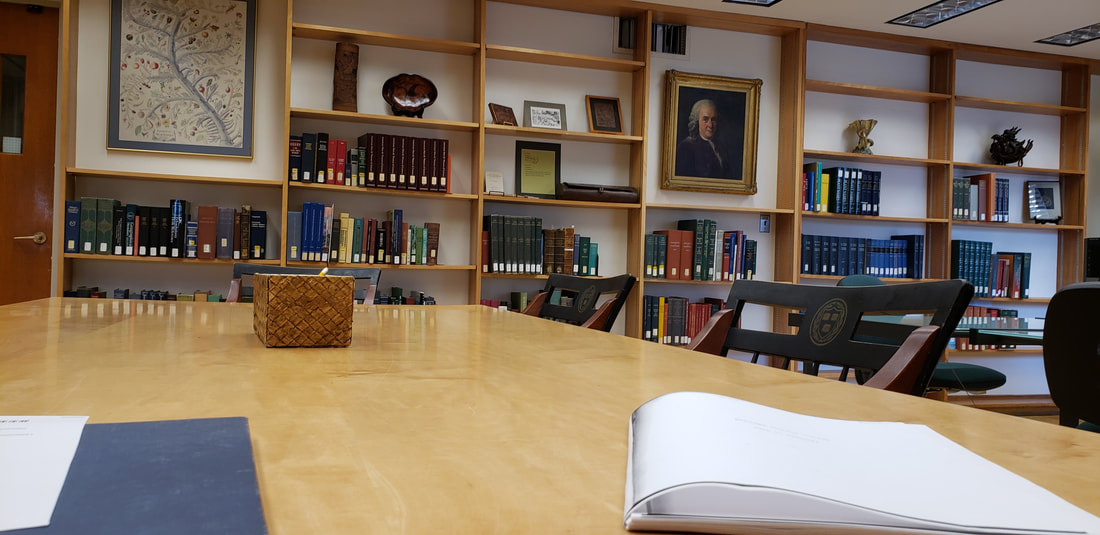

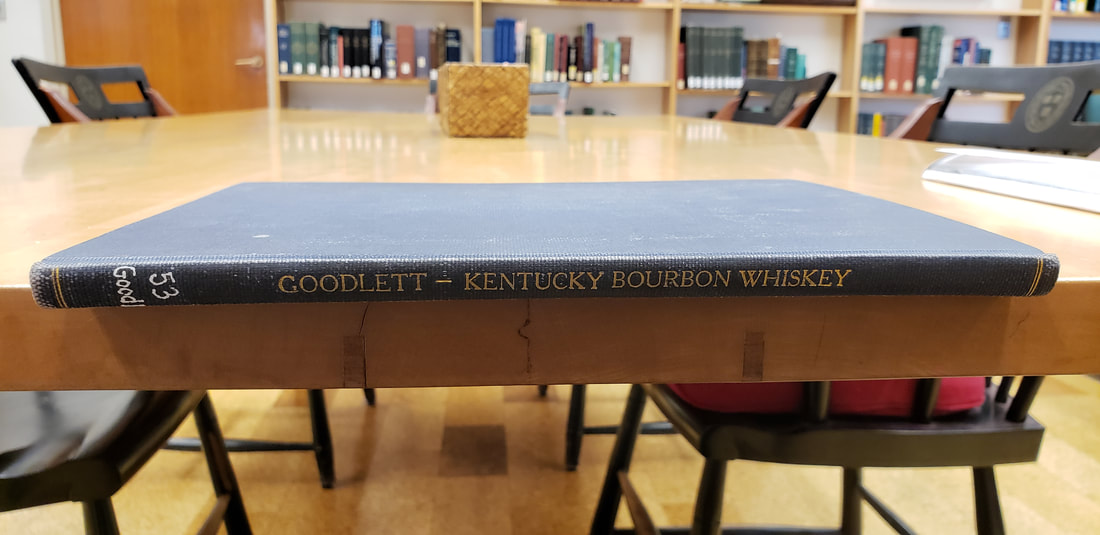

Bottles found at the site of the historic Bond & Lillard Distillery in Anderson County. Bottle stoppers, from an old distillery site in Harrison County, provided by Ray McIntyre. Photo by Rick Showalter. Bottles found at the site of the historic Bond & Lillard Distillery in Anderson County. Bottle stoppers, from an old distillery site in Harrison County, provided by Ray McIntyre. Photo by Rick Showalter. Some people use a metal detector to find hidden treasure from the past. In fact, Rick and I talked to one such fellow the other day as we were loading our bikes in the car after a short ride through the Bluegrass countryside. Rick, never shy about approaching a stranger, asked the young man, Rob Mattingly, if he had found anything of interest there on the grounds of Great Crossing Park in Scott County. That launched a far-reaching conversation that revealed, among other things, Mattingly’s startling grasp of regional and family history as well as his specific knowledge of glass bottles from 1870 to 1910. He had even done some searches on property in the Gilberts Creek area of Anderson and Mercer Counties. After hearing a brief summary of how his early family settled in Marion, Washington, and Nelson counties, we decided if he wasn’t related to the Goodletts he may well be related to the McClures—Charleen Goodlett’s family.  Whiskey bottles from Brent Hawkins' collection. Photo by Rick Showalter. Whiskey bottles from Brent Hawkins' collection. Photo by Rick Showalter. A couple of weeks before that excursion, Rick and I had joined cousins Sandy Goodlett and Ben Birdwhistell as we examined the amazing collection of a native Lawrenceburg resident, Brent Hawkins. Brent’s treasure trove of historical photos, maps, documents, whiskey bottles, and furniture—all related to Lawrenceburg and Anderson County—nearly knocked us off our feet. Most of his artifacts had been collected the old-fashioned way: by talking to area residents, expressing an interest in their family histories, and attending estate sales. Once we were able to focus our over-stimulated senses, we concentrated on the old steamer trunk full of memorabilia that once belonged to our great-grandfather, Bro. W. D. Moore. Watch for more about those findings in an upcoming blog. Nearly a year ago, Murky Press’ resident archaeologist, David Hoefer, using one of the tools of all contemporary scientists and historians—the online search—stumbled across another family relic: my father’s paper titled “Kentucky Bourbon Whiskey.” Written in 1948, that term paper—identified as a “book”—is now preserved at the Harvard Botany Libraries. We know not why or how it found its home there. It’s more of a history of bourbon distilling in the U.S. than it is an examination of the plants used in the distilling process. But, in light of the purpose of the university’s Economic Botany Library, it does make sense: “The Economic Botany Library…specializes in materials related to economic botany or the commercial exploitation of plants. Subject areas cover ethnobotany, medicinal plants, hallucinogens and narcotics, crop plants, edible and poisonous plants, herbals and other rare pre-Linnean works….” Since all of the materials in the botany libraries are non-circulating, we were struggling to get our hands on a copy. That’s when Brad Wilson, Bobby Cole’s son-in-law, stepped in to complete the excavation. A modern intrepid explorer, Brad, who happened to be in Boston for a family matter, crossed the Charles River to visit the Harvard campus in Cambridge and found his way to the proper library. There, with the kind assistance of the library staff, he dug out the infamous paper written by the war-weary, homesick graduate student. I want to thank Brad for his role in unearthing this piece of family history. And, since I’m writing on D-Day, I want to recognize Bobby Cole and John Allen Moore and Rinky Routt and George McWilliams and Lin Morgan Mountjoy and John D. Goodlette and Vincent Goodlett and Billy Goodlett and John Campbell “Pud” Goodlett and all the other boys of The Last Resort who helped deliver Europe and the Pacific region from tyranny. With a nod to my father’s four rules for field work*, history is where you find it. It’s personal. It’s regional. And it has implications for the entire world—for all of us. If we don’t honor it, recognize it, study it, and willingly take a few lessons from it, we will not endure. On this day we honor the remaining veterans of World War II. We honor those who gave their lives on the shores of Normandy and all across the globe during that conflict. And we hope that our country’s leaders will once again consider the lessons that history can teach us. Perhaps they can learn a thing or two from Rob Mattingly and Brent Hawkins, two average citizens in a red state who have invested hours and hours of their lives getting familiar with the past. *Abbreviated version of Professor John C. Goodlett’s Four Rules of Field Work: 1. Water, generally, runs downhill. 2. Plants occur where you find them. 3. Never get separated from your lunch. 4. Never go back the same way you came. For more about the Bond & Lillard Distillery, read Family Spirits. For more about the discovery of my father's paper on bourbon, and his affection for the spirit, read Bonded to Kentucky.  In memory of Brad Wilson’s mother, Dixie (1937-2019), who raised one heckuva son.

2 Comments

Barbara Fallis

6/7/2019 02:30:02 pm

Sallie, I am grateful that you take the time to research and publish your blogs. Although many times I don't the people who you reference I am always drawn in by your style of writing and the depth of information.

Reply

David Hoefer

6/8/2019 04:30:31 pm

This is a nice post, Sallie. Interesting about the bottles - historic archaeologists love 'em, too, because they can, under certain circumstances, provide very fine-grained dates for otherwise undatable features. A particular type of glass sherd in an old abandoned latrine might be the best means we have for dating the house structure that once sat there. And, ahem, how many of those 19th c. bottles were for "patent medicines"…

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

June 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed